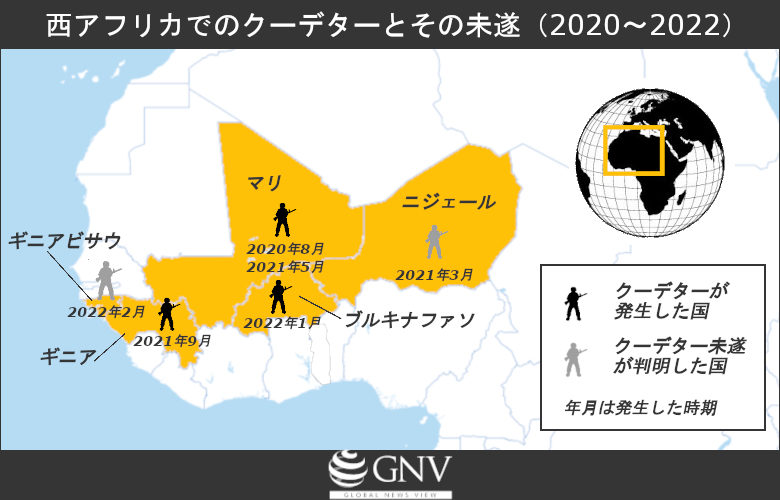

In West Africa, there were as many as six coups in roughly a year and a half. In Mali in August 2020 and May 2021, in Mali, in September 2021 in Guinea, and in January 2022 in Burkina Faso, the armed forces detained the president and others and installed military regimes. Although they did not result in regime change, there were attempted coups in Niger in March 2021 and Guinea-Bissau in February 2022. During this period, West African countries experienced six of the eight coups (Note 1) that occurred in Africa.

West African countries have a history of exploitation by Western nations: through the slave trade from the 15th century and as European colonies from the 19th century onward. Many states achieved decolonization and independence in the 1960s, but political instability persisted in many of them, and by the 1990s they had experienced as many as 42 coups that led to changes in government. Behind this were continued interference by former colonial powers after independence, new interventions by the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, as well as poverty and debt problems.

After the end of the Cold War, as presidential elections based on multiparty systems increased in the 1990s, the number of coups tended to decline. Yet as seen recently, many coups have re-emerged. What exactly is happening in West Africa?

目次

Power lust exploiting popular discontent?

The first coups of the 2020s occurred in Mali. Mali gained independence from France in 1960. It subsequently experienced regime changes via coups and a one-party system, but democratization progressed under the transitional government of Amadou Toumani Touré established by the 1991 coup. The administration of Alpha Oumar Konare, which lasted from 1992 for ten years, and the Touré administration from 2002 to 2012 governed with relative stability.

In 2012, however, an armed uprising by Tuareg seeking independence in northern Mali and the intervention of extremist groups led to the occupation of northern cities. Dissatisfied with the central government’s inadequate response, the military staged a coup in March of that year, toppling the Touré administration. The administration of Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, established in September 2013, drew public ire for corruption and lack of governance capacity. For example, against the backdrop of alleged fraud (Note 2) by the Keita government in the March 2020 parliamentary elections, which recorded a historically low turnout of 7.5%, the June 5 Movement – Rally of Patriotic Forces (M5-RFP) held repeated demonstrations. Meanwhile, armed conflict continued in the north.

As the government’s legitimacy eroded, a military coup took place on August 18, 2020. A faction of the military stormed the presidential residence, detaining President Keita along with his son and senior officials. President Keita resigned and parliament was dissolved. In their place, the National Committee for the Salvation of the People (CNSP), established by the military, seized power. Former defense minister and ex-soldier Bah N’Daw became interim president of the transitional government, and Colonel Assimi Goita became interim vice president.

Initially, citizens disillusioned by corruption and election fraud placed their hopes in the military regime led by young army officers, but the military government failed to keep its promise to implement reforms. As the transitional government partially incorporated civilian elements and military control waned, what some called a “coup within a coup” occurred in May 2021: the interim president and interim prime minister were detained, and Colonel Assimi Goita assumed the interim presidency.

The new regime that emerged then also strayed far from governance for the people: it revised the charter proposed by M5-RFP; despite agreeing to a transition to civilian rule, it appointed the defense minister as prime minister; and President Goita, who had previously been limited to powers over security, was given the authority to appoint members of the legislature.

In this way, in Mali, the military capitalized on popular disillusionment to execute a successful coup and has since imposed a new form of repression.

Scenes of the coup, Guinea (Photo: Aboubacarkhoraa / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Another case in which declining legitimacy due to distrust in the government contributed to a successful coup was Guinea. Guinea gained independence from France in 1958. From independence until 1984, the dictatorship of Sékou Touré continued, but a bloodless coup in 1984 brought Colonel Lansana Conté to power and multiparty politics was introduced. Another bloodless coup occurred in 2008, and in 2010 the opposition leader Alpha Condé formed a government.

Maintaining a long tenure of two terms (10 years) since taking office in 2010, President Condé revised the constitution in March 2020 to remove the ban on a third term and secured re-election. This constitutional revision, seen as a bid to cling to power, provoked public anger, and anti-government demonstrations by the opposition and its supporters occurred frequently, sometimes resulting in deaths.

Against this backdrop, on September 5, 2021, special forces of the army led by Colonel Mamady Doumbouya detained President Condé at his home in the capital, Conakry. The National Committee of Reconciliation and Development (CNRD) established by the army seized power, and Colonel Doumbouya assumed office as interim president.

After the coup, there were signs of public support, with people cheering from balconies in the capital and civil society groups organizing celebratory gatherings. The CNRD explained the coup as necessary to address political corruption and poverty and proceeded to draft a new charter toward a transition to civilian rule, promise free elections, and implement economic policies to avoid post-coup turmoil. While there is some optimism, given the military’s culture in Guinea, known for human rights abuses and corruption, and the difficulty of negotiations toward democratization (Note 3), many are pessimistic about escaping political corruption and poverty and about progress toward civilian rule.

Although it was a coup that succeeded while invoking the slogan of solving public disillusionment with politics, it is hard to see the interim military regime led by Doumbouya as delivering policies that meet people’s expectations.

Anti-government protest, Guinea (Photo: Aboubacarkhoraa / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Worsening instability due to extremist groups

Thus, while there are cases where coups exploit popular discontent, the causes include government corruption and election fraud. At the same time, regionally, the presence of extremist groups such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Islamic State (IS) cannot be overlooked.

AQIM is an extremist group formed in northern Algeria in the late 1990s that initially carried out repeated attacks within Algeria. From the 2000s, it gradually expanded its operations across borders, secured funding through drug trafficking, and expanded its area of activity to Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, among others. For example, as noted above, the extremist group Ansar Dine emerged in Mali, operating mainly in the north, and through coordination with AQIM, played a role in expanding AQIM’s activities.

Across the Sahel, including these areas, IS-affiliated groups such as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) are also active. Terrorist attacks on national forces and civilians occur, and clashes between extremist groups over areas of operation have further deteriorated security. The influence of extremist groups has spread southward to Togo and Côte d’Ivoire, and in Guinea there are concerns that the coup has made the country more vulnerable to attacks.

According to the Global Terrorism Index (GTI), 48% of deaths from terrorism are concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, and deaths from terrorism are increasing in Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. In Mali, attacks by extremist groups rose by 30% after the military took power (comparing 2020 and 2021), suggesting a bleak outlook. Mali’s neighbor Burkina Faso has also seen heightened extremist activity, which became a factor in its coup. The expanded conflict has left more than 7,000 dead, displaced over 1.4 million people, and put more than 3.5 million in need of humanitarian assistance in Burkina Faso alone, a situation that fueled doubts among citizens about the Kaboré government’s ability to maintain security.

Scenes from the coup, at a television station in Burkina Faso (Photo: Prachatal / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In this context, on January 23, 2022, soldiers who rebelled over the government’s failure to deal effectively with extremist groups detained President Kaboré and declared the establishment of the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration (MPSR), led by Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba and composed of military and security forces.

However, although it is known that multiple different ethnic groups are involved in extremist organizations, the newly established military regime tends to single out specific ethnic groups as members of extremist groups and place pressure on them. When human rights NGOs and foreign governments requested investigations into incidents committed by the military against those groups, the government refused to comply. As a result, there are cases in which people disillusioned by what amounts to repression join extremist organizations. Given the orientation of the post-coup military regime, there is little prospect of improvement.

Interference by major powers

France and the United States, the former colonial powers of Mali, Guinea, and Burkina Faso where coups occurred, have stood out for their military interventions. France had long deployed troops in the region and intervened militarily in Mali from 2013 onward, including Operation Serval in 2013 and Operation Barkhane in 2014. It later engaged under the banner of “counterterrorism” alongside the G5 Sahel Joint Force—composed of Mauritania, Niger, Chad, and, in addition to Burkina Faso and Mali. The United States has also been conspicuous in its involvement in the region. It has deployed multiple bases and provided military assistance to the countries concerned. For example, U.S. military aid to Burkina Faso in 2018 and 2019 has been estimated at a total of $100 million.

These forms of military assistance may also have contributed to the success of coups. The U.S. has provided extensive training to the military and police in Burkina Faso, and Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, leader of the 2022 coup in Burkina Faso, has a record of participation in U.S.-supported military training. There was also a coup in Burkina Faso in 2014, led by Lieutenant Isaac Zida, who had attended a U.S. military intelligence training course. In addition, Mali’s Colonel Goita, Guinea’s Colonel Doumbouya, and Burkina Faso’s Colonel Damiba all participated in a U.S.-led military exercise in 2019, and Doumbouya and Damiba also took part in training conducted in Paris in 2017. There are concerns that joint military exercises provide opportunities for contact among military personnel planning coups and the like.

Although France and the U.S. have intervened under the banner of “counterterrorism,” there are claims that behind this lie aims such as securing access to mineral resources and expanding political influence. West Africa has resource-rich countries: Ghana, Mali, and Burkina Faso produce more than 275 tons of gold combined; Guinea boasts the world’s largest bauxite reserves; and Niger accounts for 5% of global uranium production. For major powers, it is conceivable that even anti-democratic regimes would be acceptable partners if access to these resources can be secured cooperatively.

U.S. military training, Niger (Photo: US Africa Command / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

In this context, Russia’s presence has also become prominent in recent years. Russian private military companies, including the Wagner Group, are entering West Africa. Their aim is said to be to create dependence on the Russian military-industrial complex and gain access to African resources. In Burkina Faso, weeks before the coup, Colonel Damiba proposed using the Wagner Group against insurgents, but former President Kaboré rejected the idea. Behind this was likely Kaboré’s desire to avoid being caught up in the fraught relations between Western countries and Russia, as the West had criticized the Wagner Group’s deployment in Mali. As a result, however, having rejected the proposal twice, he likely increased resentment within the military.

While Russia is moving into the region, Western countries are showing signs of withdrawal. The French military, which at one point had 5,000 troops deployed in the Sahel, announced in February 2022 that it would withdraw from Mali. Factors behind the withdrawal include Mali’s agreement in mid-2021 to the deployment of a Russian private military company and public anger over the French deployment, among other reasons.

Even if foreign interventions are intended to halt conflict and terrorism, there are limits to what can be achieved with force alone. Unless the underlying problems of poverty and corruption are addressed, this issue will not move toward resolution. Foreign countries and their companies are also involved in resource exploitation, so the behavior of the major powers themselves must be reconsidered for the problem to be solved. In addition to major powers outside Africa, regional organizations such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the African Union (AU) are also responding. However, they have yet to present a path toward resolution.

Challenges and solutions considered through the lens of coups

As seen above, corruption and fraud among political elites, poverty, and the influence of extremist groups are heightening public discontent and creating conditions and triggers for successful military coups. While the region has long seen deep involvement from Western countries, Russia is also intervening. Moreover, while not a military intervention, China and some Middle Eastern countries are approaching the military in pursuit of abundant resources.

At present, in the West African countries where coups occurred, the interim regimes that replaced civilian governments show no signs of transitioning to civilian rule, and there is no clear road map to address corruption and poverty or to strengthen security. Some states were initially welcomed by segments of the public, but it is easy to imagine dissatisfaction rising again over time.

ECOWAS meeting (Photo: Présidence de la République du Bénin / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Meanwhile, the reach of extremist groups is expanding, and there are fears that political instability will worsen. In February 2022, at an ECOWAS meeting convened after the failed coup in Guinea-Bissau, Chair Nana Akufo-Addo described coups as “contagious,” warning of a threat to the entire region—an expression that captures concerns over regional instability.

It has been pointed out that it is important for actors sometimes viewed coolly by West African publics—Western countries and ECOWAS in particular—to nonetheless persevere in negotiating road maps for transitions to civilian rule (Note 4). Even if it seems hypocritical, by continuing to express concern and condemn coups, they can assert the legitimacy of civilian transitions and seize part of the initiative in negotiations with military regimes.

However, since military regimes are actors that operate outside established diplomatic norms, a passive stance can stall regional diplomacy and risk further deterioration in security. There are many other pressing issues, such as multiple debt burdens that contribute to poverty. Economic sanctions on military regimes can at times be necessary tactics, but they must be balanced against the impact on citizens and the need to avoid isolating countries. Due to illusions about political elites and the political manipulation of information by military regimes, sanctions can also be perceived as attacks on the public.

We should continue to watch developments in this region closely.

Note 1: During the same period, coups also occurred in Sudan and Chad.

Note 2: There were numerous allegations of irregularities, including repeated violent incidents forcing polling stations to close, the kidnapping of opposition leaders, and a Constitutional Court ruling overturning the results for 31 seats.

Note 3: Composed of the opposition, civil society organizations, and supporters of Mahmoud Dicko, former head of Mali’s High Islamic Council.

Note 4: Negotiations are underway with the regional body ECOWAS on a road map toward a transition to civilian rule, but progress is slow, and the drawn-out talks are also seen as a means to maintain dictatorial military regimes.

Writer: Sho Tanaka

Graphics: Takumi Kuriyama

0 Comments