In August 2018, three Russian journalists were ambushed and killed while traveling by car in the Central African Republic. The three had been attempting to report on the Wagner private military company (Private Military Company: PMC), which was believed to be providing facility security at mines in the country. Wagner is thought to have close ties to the Russian government (with allegations that it operates under the government’s control), and its activities are shrouded in secrecy. The Central African Republic is politically unstable, and while the attack was announced as a robbery, several suspicious points remain concerning the killings. The editor-in-chief of the media outlet that employed the three suspects that their killing may have been connected to the subject of their reporting.

Wagner is said to have first sent former Russian soldiers to support pro-Russian separatists in Ukraine and later operated in Syria, Sudan, and elsewhere in addition to the Central African Republic. That said, Wagner is just one of the growing number of private military companies around the world. Some PMCs operate in the shadows, while others expand their reach and work openly. Their activities span the land (conflict zones), the sea (anti-piracy), and the air (reconnaissance). This article looks at such companies and what they do.

Donetsk International Airport destroyed in the Ukraine conflict (Photo: Mstyslav Chernov [ CC BY-SA 4.0 ])

Business, war, and private military companies

At any time and anywhere in the world, the connection between making money and war runs deep. Indeed, behind most wars lie struggles over wealth and resources. It is not uncommon for governments or insurgent groups waging armed conflict to proceed in cooperation with domestic companies. In many conflict zones, “warlords” (Note 1) become the central actors on the ground, dominating resources and economic activity by exploiting instability in areas beyond effective government control. Moreover, since waging war requires mass production of weapons and delivering them to battlefields through global networks, the arms trade is also big business.

Manpower has long had a business dimension as well. Records show that over 10,000 foreign mercenaries fought in wars waged by ancient Egypt, and in medieval Europe and Asia, units composed of mercenaries sometimes formed major fighting forces. During colonization, it was often companies rather than the metropole’s government that were at the forefront; companies themselves fielded armed forces to carry out the slave trade and the seizure and occupation of resources and land.

Modern PMCs—corporations providing military-related services—began appearing in the West after World War II and surged after the Cold War, as direct military interventions around the world by the United States and the Soviet Union declined. In the 1990s, two firms stood out in particular: Executive Outcomes (EO), composed mainly of veterans from the partially disbanded South African military after the end of apartheid, and Sandline International, founded by British military veterans. They were contracted by governments in Angola, Sierra Leone, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea, as well as by major oil and mining companies. In Angola and Sierra Leone in particular, EO, while cooperating with the government military, used its own troops and attack helicopters and infantry fighting vehicles to successfully repel and drive out insurgent forces.

A private military company employee teaching Afghan soldiers how to use mortars (Photo: U.S. Army photo, Capt. Jarrod Morris [Public domain])

However, PMCs expanded most in the United States. When the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq began, much of U.S. military activity was outsourced to private companies. During World War II, about 10% of U.S. military-related personnel were employees of outside contractors; by the 2003 Iraq War, that figure had jumped to 50%. As of 2016, the number of civilians deployed to Afghanistan under U.S. military contracts was about three times the number of U.S. troops there, and about twice in Iraq. Looking at fatalities as well, contractor civilians outnumbered U.S. military personnel. Large U.S.-based PMCs such as DynCorp and Academi (Note 2) employ over 10,000 people and generate revenues in the billions of dollars. Beyond Iraq and Afghanistan, they have operated in many conflict zones and unstable regions, including Colombia, Yemen, Somalia, and South Sudan.

If we include companies that provide general security in peacetime, the scale is even larger. Among companies active in conflict zones, some provide general security services; taken together, they are referred to as private military and security companies (PMSCs). One standout is the UK-based G4S, which operates in 125 countries and is even the world’s second-largest private employer by headcount (625,000). Although it conducts military activities, its focus is on security. Other firms whose main business is military operations also sometimes work in countries not at war. For example, Blackwater (now Academi) was contracted for security in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and to guard missile-defense radar in Japan.

A private military company employee guarding U.S. State Department personnel in Iraq (Photo: Jamesdale10 [ CC BY-2.0 ])

Questionable and dangerous activities

The activities of PMCs can be broadly divided into three categories. First is “the provision of force,” meaning frontline activities. This includes combat-related operations, security, and reconnaissance via aircraft and drones. Second is “the provision of logistics,” such as transport and supply-chain support. Third is “consulting,” including training and education for national militaries as well as analysis and advisory services. The first category—providing force—is where problems most often arise.

One major issue is that PMCs are profit-seeking organizations. If there is no prospect of profit, they will not deploy. Subcontracting under large militaries in advanced countries might be seen as an extension of the national military, but when contracted by poorer governments, fees may be tied to natural resources, paid via shares of mine revenues and the like. In some cases, even when contracted by a government, securing natural resources is prioritized over public safety, meaning the core activities become suppressing rebels or recovering and guarding mines rather than longer-term stabilization and security sector work. PMCs may also be contracted not by local governments but by foreign mining and oil companies, potentially aiding those companies’ illegal extraction of mineral resources.

Because profit is the objective, personnel issues also arise. Unlike national militaries, PMCs do not require a particular nationality, but pay varies by nationality and background. Veterans from advanced countries often have high-level training and therefore command higher pay, whereas people from poorer countries can be hired for less—an embodiment of global inequality. For example, in 2016 the conduct of the UK’s Aegis (Note 3), which had been contracted to guard U.S. military facilities in Iraq, drew attention. Initially, thanks to lucrative U.S. contracts, it hired primarily veterans from advanced countries, but as fees declined it hired veterans from Nepal at lower wages, and eventually sourced even cheaper labor from Africa. In seeking personnel with military experience, it emerged that former child soldiers from Sierra Leone were among those hired, which became a scandal.

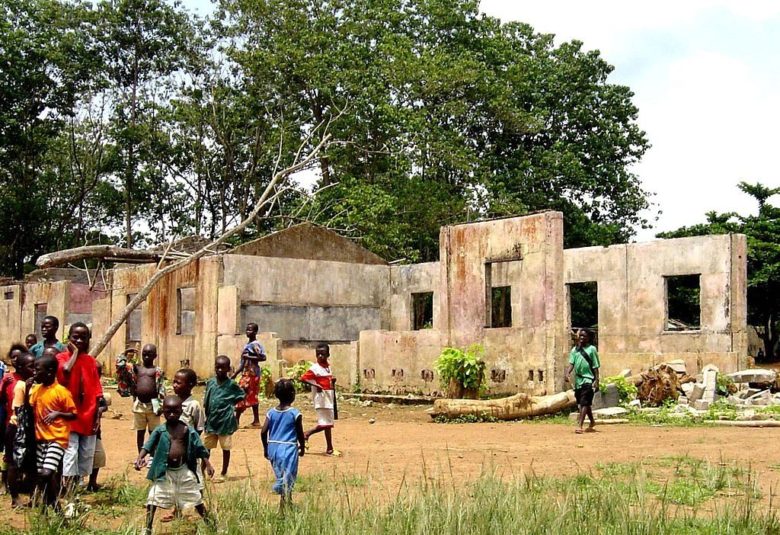

Children playing near a school destroyed in the Sierra Leone civil war (Photo: Laura Lartigue [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Who commissions PMCs and for what purpose is also at issue. Many PMCs claim they are commissioned by legitimate governments and operate under those governments’ laws. However, they are sometimes hired covertly and illegally by insurgents or companies. In 2004, for example, a group of mercenaries attempted a coup in Equatorial Guinea; the son of former UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher was convicted for his involvement, and there were suspicions that the former prime minister herself was aware of it. Even when the client is an internationally recognized government, if the commissioned activities amount to repression of civilians or complicity in war crimes and human rights abuses, questions of responsibility are difficult.

For example, in the Yemen conflict, into which a coalition led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has intervened, numerous acts amounting to war crimes and human rights violations have been documented. The UAE, a key member of the coalition, relies heavily on PMCs. Both Academi and DynCorp have been contracted, and the UAE government has also directly hired mercenaries from Colombia and elsewhere in Latin America with extensive conflict experience. The UAE also hires foreign military veterans on an individual basis. For example, the head of its helicopter unit is a retired U.S. servicemember; in 2017, helicopters fired multiple times on a boat headed for a Yemeni port, killing more than 40 Somali refugees. Although the UAE denied involvement, it is highly likely the act was carried out by UAE helicopters.

Another serious concern is whether PMCs have clear chains of command and rules of engagement and whether training and education on human rights and war crimes are thorough. In Iraq, multiple killings by Blackwater personnel were reported, most notably a 2007 incident in which company staff, while escorting a U.S. embassy convoy, opened fire on civilians, killing 17 people.

A Blackwater helicopter conducting reconnaissance after a bombing in Iraq (Photo: U.S. Air Force, Master Sgt. Michael E. Best [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Such cases may be brought to the International Criminal Court (ICC) if they constitute war crimes. They may also be tried in the country where the incident occurred or under the judicial systems of the PMC personnel’s home countries. In fact, in the Blackwater case above, four men were convicted in the United States. Even absent such incidents, the very extent to which PMCs may participate at the front is in question. In 1989, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution banning, among other things, the recruitment and use of “mercenaries,” but activities such as guarding and protection remain a gray area. And even where recognized as lawful activities by legitimate organizations, PMCs need to be strictly regulated and monitored.

A savior for peace operations?

In 2015, Nigeria sought assistance from the PMC STTEP (Note 4) in its fight against the insurgent group Boko Haram. In its war with the government, Boko Haram committed kidnappings and terrorist acts and was notorious for pledging allegiance to IS. With other countries reluctant to intervene, the Nigerian government, with STTEP’s support, was able to deal a significant blow to Boko Haram in a relatively short time.

This was by no means a peace operation, and as noted above many issues and challenges remain around PMCs. However, in this case it is undeniable that a PMC played an effective role in helping the government restore governance and security. PMCs certainly pursue profit, but states likewise pursue national interests. No matter how grave a humanitarian crisis may be abroad, if it does not register as important to national interests, states are reluctant to act. Even when something is deemed important to national interests, governments often outsource to PMCs instead of deploying their own troops, since the deaths of their own soldiers carry political costs, whereas contractors’ losses can be dismissed as “at their own risk.”

Accordingly, the use of PMCs is increasingly being discussed even in UN peacekeeping operations (PKO). The UN and its agencies already contract PMCs for facility security, protection, and training, but PMCs have not yet participated in PKOs themselves. At present, developed countries provide funding for PKOs but contribute few troops. Many of the units provided—mostly from so-called developing countries—are not well trained. And because incentives are low for any country to fully commit to PKOs, in that context there are emerging calls to cautiously and conditionally deploy PMC personnel as PKO soldiers.

PMCs are easily cast as villains in international politics. The day when they are commissioned for PKOs and contribute to the restoration of peace may not be far off.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres inspecting a PKO mission in the Central African Republic (Photo: UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe [ CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 ])

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

Note 1: A warlord is an armed actor that pursues private interests. They arise in areas of weak government authority and become de facto rulers of those areas. Unlike insurgents, they do not seek to overthrow the government and avoid clashes with government forces. By monopolizing the security environment in their areas of control/activity, they can also control economic activity and profit from it.

Note 2: Academi was founded in 1997 by U.S. military veteran Erik Prince as Blackwater. After a series of scandals, it rebranded as Xe Services in 2009 and became Academi in 2010.

Note 3: Aegis was acquired in 2015 by Canada’s GardaWorld.

Note 4: STTEP (Specialized Tasks, Training, Equipment and Protection) is run by South African veteran Eeben Barlow, the founder of Executive Outcomes (1989–1998), often considered the original modern PMC.

記事興味深く拝読しました。民間軍事会社というと

つい「悪」や「紛争に介入する」という

イメージがありますが、PKOに行ってもらう

というのはいいアィディアかと思いました。