In Sudan, the armed conflict that broke out in April 2023 has expanded, triggering one of the world’s largest humanitarian crises. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), more than 18,500 deaths were recorded between April 2023 and June 25, 2024. However, this figure only reflects deaths confirmed in combat, and the actual toll is believed to be higher. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 9.2 million or more people have been forcibly displaced; over 7.2 million are internally displaced and nearly 2 million have fled to neighboring countries. A study by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), established by the Norwegian Refugee Council, found that Sudan recorded the highest number of conflict-related internally displaced people in 2023. In Sudan, and in neighboring South Sudan and Chad, more than 28 million people are facing food shortages, and the situation is extremely severe.

Despite this, Sudan continues to be “forgotten by the world,” as stated by Martin Griffiths, the UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs at the February 2024 briefing of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), underscoring the low level of global attention. This article looks into the background of the conflict in Sudan and the current situation.

Scenes of Khartoum (Photo: Christopher Michel/Flickr[CC BY-NC2.0])

目次

History of the conflict

To understand the conflict Sudan faces today, we need to go back to another conflict that began in 2003: the war in Darfur.

Sudan gained independence from British colonial rule in 1956 but has long experienced authoritarian regimes. From 1989, President Omar al-Bashir, who seized power in a coup, ruled the country. Under this political system, clashes between the central government and the periphery occurred continuously. Amid widespread poverty, resentment grew in outlying regions over marginalization by a wealth-concentrated center. In the peripheries, diverse ethnic identities existed, and conflicts along those lines also emerged.

After years of armed conflict with the central government, southern Sudan (later South Sudan) was moving toward independence. In Darfur as well, local grievances escalated into armed conflict. Darfur, in western Sudan bordering Libya, Chad, and the Central African Republic, was a region marginalized by the central government. Poverty driven by scarce resources and disputes over grazing lands due to water shortages worsened, leaving the region economically distressed. At the peak of tensions in 2003, anti-government forces protesting the unequal distribution of economic resources emerged; groups calling themselves the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) launched an armed uprising against the Sudanese government. The government, in turn, armed a Darfur-based militia known as the Janjaweed to fight the rebels. The Janjaweed attacked villages and carried out repeated massacres. Fighting continued between the anti-government forces, including the SLA and JEM opposing the Bashir regime, and the Janjaweed and the Sudanese Armed Forces.

Since the outbreak of armed conflict in 2003, about 300,000 people have lost their lives in Darfur, and millions have been displaced. Among them, 400,000 people were forced to flee to neighboring Chad, and the situation overlapped with conflicts in Chad and the Central African Republic. As killings of civilians and other atrocities escalated, the UN sounded the alarm. UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan called Darfur “the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.”

Negotiations toward ending the conflict continued, and on May 5, 2006, with support from the United Nations and others, the Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA) was concluded under the African Union (AU). In 2009, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant for Sudan’s President Bashir on charges of crimes against humanity, genocide, and war crimes in Darfur. In February 2010, the Sudanese government and JEM signed a “framework agreement” for resolving the Darfur issue. Although there were moves toward peace, fighting between the Sudanese government and anti-government forces continued to break out.

Darfur agreement signing (Photo: UNAMID /Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND2.0])

From the Janjaweed militias that took part in the Darfur conflict in the 2000s, a paramilitary force—the Rapid Support Forces (RSF)—emerged in 2013. Under the Bashir regime, the RSF was used to suppress anti-government movements in Darfur and other regions. In 2015, it was even deployed alongside the national army to the war in Yemen. That same year, it was granted the status of a regular force. However, it retained an independent chain of command.

A faltering central government

As President Bashir held onto power, public discontent remained unresolved. The trigger for renewed mass protests came in December 2018, when the price of bread tripled overnight, further straining lives already in hardship. The protests soon spread from the capital to many parts of the country, and repression by the army caused casualties. In April 2019, after massive demonstrations, the military took action. Ultimately, the national army and the RSF staged a coup, and the military high command announced the ouster of President Bashir.

In response to strong public opposition to the coup leaders forming a transitional government, a joint civilian-military governing body was established in August 2019. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, formerly a close aide to ex-president Bashir and head of the transitional authority, assumed leadership, and the RSF commander, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo—known as Hemedti—was appointed deputy.

Scenes from the 2019 revolution (Photo: Hind Mekki/Flickr[CC BY2.0])

With large-scale demonstrations continuing, negotiations mediated by the AU and Ethiopia in August 2019 led to the signing of a constitutional declaration paving the way for a transition to civilian rule. It provided for a three-year transitional period of joint civilian-military governance. A Sovereignty Council composed of civilians and military personnel would govern, and economist Abdalla Hamdok was nominated as prime minister, seemingly beginning a transition. Hamdok sought to resolve Sudan’s economic crisis through reforms. Perceiving their interests threatened by these reforms, military generals moved to “correct the course of the revolution,” staging a military coup that removed Hamdok from office. In response, protests in Khartoum demanding civilian control and Hamdok’s return intensified. The army briefly reinstated Hamdok as prime minister, but he later stepped down amid the security forces’ unchecked violence.

Since then, Sudan has had no civilian leader, with General Burhan holding power as the de facto head of state. In December 2018, a framework agreement toward forming a transitional government was reached among the Sovereignty Council, some pro-democracy forces, and the RSF. However, the struggle over legitimacy and control between the national army and the RSF intensified thereafter. A major point in negotiations was the role of the RSF. The agreement mentioned integrating the national army and the RSF, but without a deadline; Burhan advocated 2 years, while Hemedti insisted on 10 years.

Outbreak of conflict

Tensions rose over plans to integrate the RSF into the army. Amid disputes over the power of the security forces and the exercise of state authority, the timing of the RSF’s integration into the army became the central sticking point. On April 8, 2023, Burhan and Hemedti held talks. While there were moves such as Burhan demanding the RSF withdraw from Hemedti’s base in El Fasher, Darfur, and halt its inflow into Khartoum, on April 15 fighting erupted, reportedly triggered by gunfire from the national army.

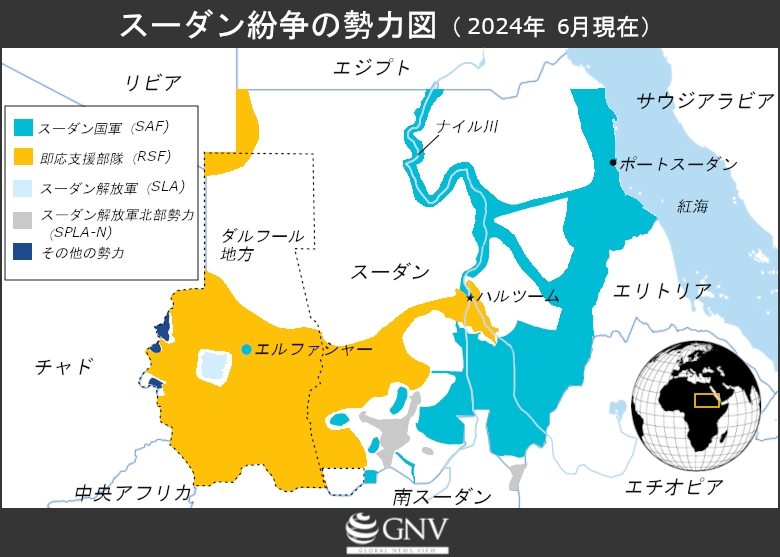

Created based on data from the Sudan War Monitor

Since the fighting erupted in Khartoum, it quickly spread to other parts of Sudan, including Darfur, North Kordofan in the center, and Gezira in the east-central region. The Sudanese Air Force closed the country’s airspace and struck multiple RSF positions on the outskirts of the capital. Within months, the RSF consolidated its position in Khartoum, besieged the army’s headquarters there, and pushed Burhan to Port Sudan, a Red Sea coastal city. On the western side of the capital, intense fighting raged in Darfur, the RSF stronghold. Four cities in Darfur fell to the RSF, which then prepared to seize El Fasher, capital of North Darfur. Beyond Darfur, the RSF also controls parts of North Kordofan and South Kordofan, holding Sudan’s largest oil field and strategic supply routes to the capital. By late 2023, the RSF tightened its grip on urban areas and weakened the army in Khartoum. In November, White Nile State, located 40km south of Khartoum, fell, and the RSF continued its advance southward to the Gezira state capital, Wad Madani, moving in.

The army withdrew from Wad Madani and has come under RSF attacks. The RSF also pressured the army to withdraw from strongholds in South and West Darfur, and now controls almost all of Darfur. Darfur is a major source of revenue for the RSF and a base of support for Dagalo. Buoyed by successes in Khartoum and Darfur, the RSF has been pushing south and east to force the army to capitulate. The army has responded with RSF armed drones and worked to retake Gezira, shifting momentum toward the military. However, heavy fighting in Wad Madani and El Fasher has caused many deaths, raising concerns of further deterioration.

Burhan and Hemedti (Photos: left: President.az/Wikimedia Commons[ CC BY4.0]) right: Government.ru/Wikimedia Commons[CC BY 4.0])

Humanitarian issues

After more than 1 year of fighting, the situation inside Sudan is dire. As noted at the outset, since the outbreak in April 2023 through June 2024, more than 18,500 people have been killed. Also, since 2023, 9.2 million or more people have been displaced within the country and to surrounding areas, facing the world’s largest displacement crisis. Widespread conflict-related sexual violence is also a serious problem, highlighted by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

Food crisis is another challenge, with 18 million people facing severe shortages of essentials such as food, clean water, and fuel. Inflation and food scarcity have made food increasingly hard to obtain. Sudan is also affected by extreme weather events such as floods and droughts. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the country’s 2024 cereal production is expected to fall to below 46% of the 2023 level, a severe outlook. Food insecurity affects not only Sudan but also neighboring South Sudan and Chad, with a combined total of 28 million people affected.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of April 2024 there were more than 11,000 suspected cholera cases and over 4,000 cases of measles, malaria, and dengue reported, and the collapse of the healthcare system is worsening.

Due in part to the conflict, Sudan’s economy shrunk by 18.3%, squeezing the livelihoods of many people in the country.

Scenes in a refugee camp (Photo: Global Partnership for Education/Flickr[ CC BY-NC-ND2.0])

Diplomatic relations

One reason the conflict in Sudan has continued intensely for over 1 year is foreign involvement. In particular, relations with Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia have had a major impact. Egypt supports the Sudanese army and is reported to provide military assistance. Egypt borders northern Sudan, and both countries share a background in which the military has played a leading role. Meanwhile, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia support the RSF. To fight the Houthi movement allied with the UAE and Saudi Arabia, Hemedti dispatched thousands of RSF mercenaries to Yemen. Russia’s paramilitary group Wagner also provided weapons to the RSF in exchange for access to gold resources under its control.

In May 2023, Saudi Arabia and the United States attempted to mediate the conflict, bringing together the Sudanese army and the RSF in Jeddah. In July, Kenya acted, proposing the deployment of peacekeepers from the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a regional bloc in East Africa, but Sudan’s neighbors Chad and Egypt are not IGAD members. In response, the two countries held a meeting in Cairo and convened a summit of Sudan’s neighboring countries. Coordinating with other regional frameworks, these efforts aimed to resolve the conflict peacefully. Attempts at peace talks by foreign governments and international organizations have been made at least 16 times, but there are no signs of mediation taking hold, and global efforts to end the war in Sudan are not working. Some point to the fact that many countries are acting based on their own interests as one reason.

As things stand, there is no end in sight to the conflict in Sudan, and many people are suffering out of the global spotlight. We must continue to pay close attention.

Writer: Junpei Nishikawa

Graphics: MIKI Yuna

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me. https://www.binance.info/zh-CN/register?ref=WFZUU6SI