On September 11, 2021, 20 years had passed since the terrorist attacks in the United States (hereafter 9.11). 9.11 was not only an incident that occurred within the United States; it also became the trigger for the United States to launch military operations against numerous countries and groups. After the attacks, the United States also began unprecedented large-scale surveillance activities at home and abroad, and 9.11 became an event that had a major impact on the international situation.

Re-reporting an event on the occasion of a notable anniversary is called anniversary journalism. Anniversary journalism plays the role of looking back on past events and summarizing subsequent developments after those events occurred. Learning about past events around the world and linking them to current affairs can help us understand today’s international situation. In fact, in Japan as well, during the period from August to September 2021, marking 20 years since 9.11, many reports related to 9.11 and the subsequent situation were seen.

So how did the Japanese media report on 9.11 at this milestone of 20 years since the attacks? This article examines from multiple perspectives whether the media has been able to reflect the reality of 9.11 and the subsequent 20 years.

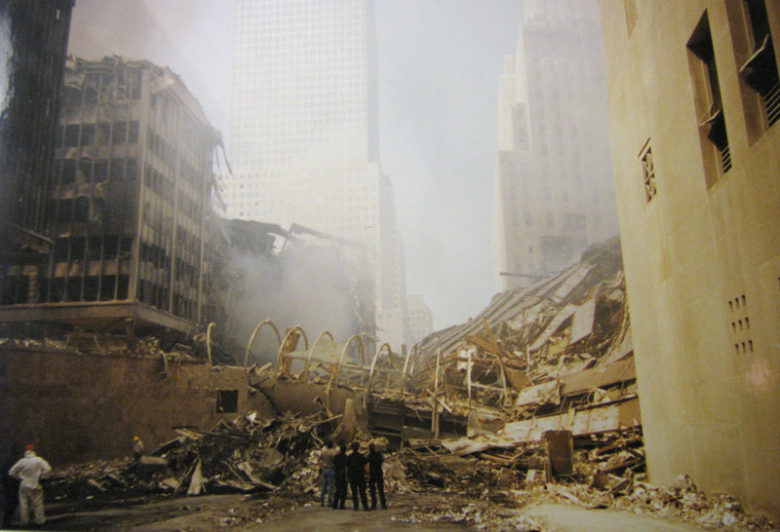

The Pentagon two days after the attacks (Photo: Cedric H. Rudisill / PICRYL)

目次

9.11 The reality of the coordinated terrorist attacks

Before analyzing reporting on 9.11, let us briefly review the events of that day. According to the U.S. government’s report, on the morning of September 11, 2001, 19 people, said to be members of the extremist group al-Qaeda and primarily Saudi nationals, simultaneously hijacked four U.S. passenger aircraft. They flew two of the four planes into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City (WTC Building 1 and WTC Building 2). Of the remaining two aircraft, one struck the Department of Defense (the Pentagon) in Washington, DC, and the other crashed in a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Excluding the 19 hijackers, 2,977 people died in the attacks. The U.S. government’s view is that the terrorist plot, devised five years earlier under al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, was carried out.

However, there are several points of doubt regarding the U.S. government’s account of 9.11. First, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) reportedly did not find conclusive evidence linking bin Laden to the attacks and did not place him on the wanted list for that charge. Nevertheless, doubts remain about the U.S. government’s conclusion that bin Laden was the mastermind.

Collapsed WTC 7 (Photo: jphillipobrien2006 / Flickr[CC BY-NC 2.0])

In addition, various questions have been raised about the collapse of buildings and the piloting of the planes on the day of the attacks. For example, WTC Building 7, one of the high-rises at the World Trade Center, collapsed that day at nearly free-fall speed, despite not having been struck by an aircraft. According to the U.S. government, Building 7 fell due to fires that spread from other collapsing buildings; if true, this would be the first time in history a high-rise collapsed primarily because of fire. Research by the University of Alaska concluded that the collapse of Building 7 could not have occurred unless all columns in the structure failed simultaneously, and therefore was not caused by fire. There is also a group of architects and engineers that argues government investigations into the building collapses do not adequately explain the causes. They also question whether the crashes alone brought down WTC Buildings 1 and 2. Furthermore, there is a group of pilots who doubt that individuals with no commercial airliner experience could have flown the aircraft with such advanced precision. In this way, it has been pointed out that some aspects of what happened that day cannot be scientifically demonstrated.

Twenty years after the attacks

Immediately after the attacks, the administration of U.S. President George W. Bush demanded that the then Taliban government in Afghanistan hand over, unconditionally, al-Qaeda leaders including bin Laden for capture. In response, the Taliban asked for evidence that bin Laden had been involved in 9.11, but the United States refused to negotiate and proceeded with military intervention. On this occasion, President Bush declared a “war on terror” not only against al-Qaeda but against any organization that carried out terrorism.

The United States set its sights not only on capturing bin Laden but also on toppling the Taliban government. The U.S. government deployed U.S. Army Special Forces and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and, in cooperation with other allies and anti-Taliban armed groups in Afghanistan, the coalition toppled the Taliban in two months. Many of bin Laden’s fighters, Taliban leaders, and combatants fled to Pakistan. On the other hand, some have argued that the appropriate response to 9.11 should have been criminal measures—such as internationally indicting the hijackers as criminals—rather than military action. Moreover, the military intervention to overthrow the Taliban is said to have been illegal under international law. Yet international organizations and countries have not fully pursued this issue. Japan clearly supported the United States in the war in Afghanistan, enacted the Anti-Terrorism Special Measures Law, and provided support such as refueling operations in the Indian Ocean. Although the Taliban seemed to have been crushed by the coalition invasion for a time, they resurfaced, and in 2021 seized the capital and retook power.

Scenes from the Iraq War (Photo: WikiImages [Pixabay License])

It has also been reported that, immediately after 9.11, the U.S. government planned to carry out military attacks against a total of 7 countries. This plan was subsequently implemented in many countries. One of those 7 countries was Iraq. The Bush administration repeatedly made false statements that Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq was connected to al-Qaeda and involved in some way in 9.11, and that it possessed weapons of mass destruction, and then invaded Iraq. In reality, however, Iraq had no ties to al-Qaeda, and no weapons of mass destruction were found. The United States overthrew the Hussein regime and occupied Iraq, which led to continuing conflict. The U.S. occupation of Iraq also contributed to the rise of the Islamic State (IS), and later the United States intervened in Syria in pursuit of IS.

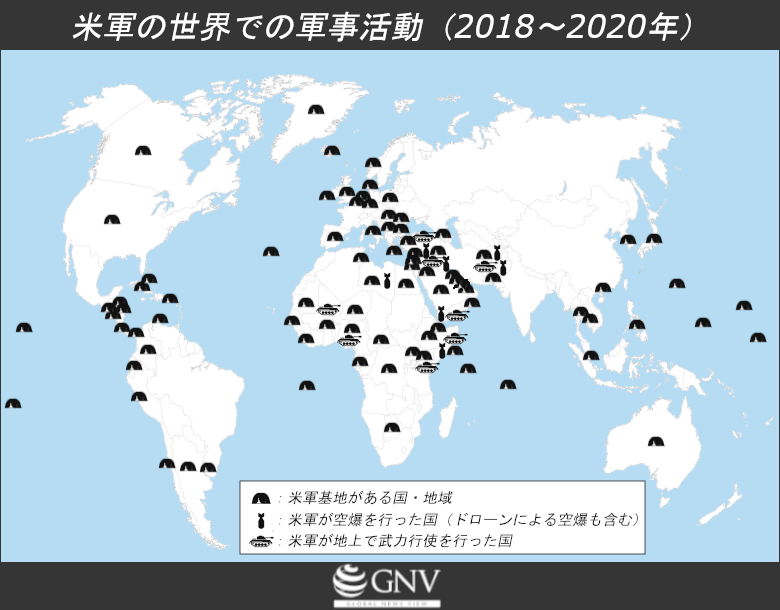

9.11 Afterward, the countries in which the United States intervened militarily under the banner of “counterterrorism” were not limited to Afghanistan and Iraq. The United States has also conducted military interventions and airstrikes. As an example of airstrikes, the United States carried out assassination programs in Yemen and Pakistan in which drone strikes killed 1,147 people, including civilians. Drone attacks were actively employed under the Obama administration. At the same time, the Obama administration helped entrench the concept of a “humane war” (※1) to enable such attacks. There is also a view that the drone airstrikes carried out by the United States themselves constitute terrorism. In addition, among U.S. airstrikes, there are numerous cases such as those in which Pakistani soldiers unconnected to terrorist groups were caught up, and airstrikes in Somalia that killed civilians.

Created based on data from Al Jazeera and Brown University

These military actions in other countries have continued to expand and are ongoing today. For example, from 2018 to 2020 the United States conducted military activities in 85 countries, and military operations under the banner of “counterterrorism” have in recent years extended to a wider range of regions. As of 2020, the United States is also said to maintain about 750 military bases in at least 80 countries around the world. In addition, working with allies and others, the United States has carried out kidnappings, extraordinary renditions, and torture of numerous people suspected of terrorism.

Costs and consequences

So, what kinds of sacrifices have been brought about by the wars the United States has waged around the world since 9.11? First, looking at the human toll, the direct deaths in these wars are said to exceed 900,000. Nearly half of the dead were civilians. Even among the confirmed counts alone, about 200,000 in Iraq, about 95,000 in Syria, about 46,000 in Afghanistan, and about 24,000 in Pakistan were killed. “Direct deaths” here include civilians who died as a direct result of war—such as from bombings and shootings—as well as soldiers of forces opposing the U.S. military, allied soldiers, U.S. troops, humanitarian aid workers, and journalists. This does not include indirect deaths caused by disease, displacement, and lack of access to food and drinking water resulting from war; therefore, the actual total number of victims is presumed to far exceed 900,000.

Next, what has been the financial cost of these wars? Ironically, there is no comprehensive data on the financial costs borne by the countries whose territories were extensively destroyed by U.S. military interventions. However, there are data on the costs to the United States. According to a research project at Brown University, the United States has spent an estimated 8 trillion U.S. dollars on wars in the 20 years since 9.11. The breakdown is 2.3 trillion for the war in Afghanistan, 2.1 trillion for the wars in Iraq and Syria, and 355 billion for other wars. Of the military budgets spent, as much as half is said to have gone to defense contractors such as weapons manufacturers. After 9.11, many activities in the war zones were outsourced to private companies, showing a trend toward the privatization of war.

Another price paid after 9.11 was people’s privacy. In other words, a surveillance society accelerated around the world, starting with the United States. Within weeks of the attacks, under the banner of “counterterrorism,” the U.S. Congress passed the USA PATRIOT Act. Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act gives the government broad authority to demand from companies records related to people who may be involved in terrorism. The National Security Agency (NSA) interpreted Section 215 expansively and began operating a massive surveillance program called PRISM that enabled the collection from telecommunications firms of telephone records, emails and internet call records, videos, images, SNS data, and other personal information. It is said that information was obtained in large quantities not only from telecom companies but also from major firms such as Google, Facebook, Yahoo, and Microsoft. In 2013, this was leaked by Edward Snowden. Later, a U.S. court ruled that the NSA’s collection violated the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act and was illegal.

Although the PATRIOT Act was enacted on the premise that collecting information would prevent terrorism, has it in fact prevented attacks? The U.S. government has taken the position that Section 215, in particular, plays an important role in counterterrorism, but as of 2015 the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB) found no cases in which the PATRIOT Act contributed to preventing terrorism.

Surveillance cameras installed throughout modern society (Photo: Px4u by Team Cu29 / Flickr[CC BY-ND 2.0])

9.11 Analysis of anniversary journalism

As described above, the 9.11 coordinated terrorist attacks became the starting point for numerous wars and military interventions over the past 20 years, as well as for significant infringements on the privacy of ordinary people. How did the Japanese media look back on these 20 years? To analyze 9.11-related reporting in 2021, we examined three papers—Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun (※2). We found 88 relevant articles in Asahi, 89 in Mainichi, and 17 in Yomiuri, for a total of 194 articles, concentrated mainly around September 11, 2021. Below, we collectively analyze coverage across the three papers.

Looking at 2021 coverage related to 9.11, the content can be broadly classified into three types: articles on the current situation 20 years after 9.11; articles on developments over the 20 years since 9.11; and articles about the incident itself. The breakdown was 96 articles (49%) on the current situation; 80 articles (41%) on developments since 9.11; and 20 articles (10%) on the incident itself.

Of the 20 articles about the incident itself, 18 were based on interviews with individuals who were at the scene at the time or with bereaved family members. There were no articles that addressed the kinds of questions mentioned above regarding who carried out the coordinated terrorist attacks and how they were carried out.

Also, perhaps due in part to the U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan in September 2021, articles on the current situation—including such breaking news—accounted for a large share at 49%. Needless to say, reporting on the “now” plays an important role. However, to assess how the media has remembered the impact of the attacks over these 20 years, we focus here on analyzing articles that described developments since 9.11.

First, which countries did the articles focusing on the 20 years since 9.11 relate to? Was there regional bias? Looking at the 80 articles by region (※3), about 39% concerned the United States, while Afghanistan and Iraq—where large numbers of U.S. ground forces were deployed—accounted for about 29% and about 12% respectively. These three countries together accounted for about 80% of the coverage. Among other countries, the share was higher for Japan, China, and Russia, in that order, while other countries each accounted for less than 1%. Articles on Japan, China, and Russia tended to take a Japanese perspective or broaden the discussion to U.S.-China and U.S.-Russia relations since 9.11. Meanwhile, the numbers of articles on Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia—countries where the U.S. conducted airstrikes and other military actions—were only 1.1 for Pakistan, 0.5 for Yemen, and 0 for Somalia.

As noted above, the United States still maintains about 750 bases around the world and has conducted military activities in 85 countries under the label of “counterterrorism,” but coverage was heavily biased toward certain regions. Only 3 Asahi articles mentioned the approximately 750 U.S. military bases or U.S. military activities in 85 countries; Mainichi and Yomiuri did not address them. There were also 0 articles on U.S. abductions and torture or on assassinations by drones highlighted above. Regarding Japan’s refueling support to U.S. forces, there was only 1 article in Asahi.

The Iraq War was reported as a 9.11-related matter in 9.5 articles. However, only 1 article pointed out that the Hussein regime had no links to al-Qaeda, and only a total of 4.5 articles across the three papers mentioned that no weapons of mass destruction were found.

On the other hand, there was a certain amount of coverage of human and financial costs: 31 articles mentioned human casualties—including civilian and U.S. military deaths—in various wars and military operations, and 25 articles mentioned the large U.S. expenditures over the 20 years of war. Looking more closely at the human toll, although civilian deaths in each country far outnumbered U.S. military fatalities, there were 15 articles describing civilian casualties and 14 describing U.S. military losses (※4). Among the articles that discussed civilian casualties, all referred either to the overall civilian toll or to civilian casualties in Afghanistan and Iraq; none addressed civilian losses in other regions. Regarding U.S. war spending, 18 of the 25 articles listed specific figures, while none mentioned the total financial damage borne by the countries targeted by the wars.

Detention facilities at the U.S. military base in Guantánamo, Cuba (Photo: Shane T. Mccoy / U.S. National Archives & DVIDS)

Coverage of the surveillance-society issues that expanded after 9.11 was scant. There was only 1 article in Asahi that briefly mentioned the “emergence of a surveillance society enveloping the world.” In today’s world, where every region is connected via the internet, surveillance is a major issue affecting not only the United States but also Japan. The amount of coverage in Japan is not commensurate with the seriousness of the problem.

The term “war on terror”

One phrase that repeatedly appeared in the articles was “war on terror” (or “fight against terrorism”). The term “war on terror” was used by the Bush administration when it invaded Afghanistan immediately after 9.11 . Some have argued that by using this phrase, the administration deliberately blurred the scope of the “enemy,” thereby enabling it to wage war anywhere and justify it . However, “terror” is not a warring party or group but a method of violence, and one cannot wage war on a method. Thus, the term is political propaganda by a belligerent, and there is a problem with journalism using it uncritically. Since 2008, even the U.S. government has stopped using the term.

Even in 2021, when the problems with the term “war on terror” were publicly recognized, Japanese media continued to use it. Looking at the frequency of “war on terror” and similar phrases (※5), the term appeared with quotation marks in 30 articles and was used 37 times, and without quotation marks in 35 articles and used 61 times. All three papers—Mainichi, Yomiuri, and Asahi—used the term, and in several cases it appeared in headlines.

Furthermore, as noted above, there is no evidence linking al-Qaeda and the Hussein regime in Iraq, so describing the Iraq War as part of the “war on terror” is highly problematic. Yet Japanese newspapers also used the term for that war. For example, in the October 23, 2021 Mainichi article “On-the-ground report from Iraq: Beyond 20 years of turmoil: Part 1—Fallujah: A city of fighting, scars and reconstruction; Sunni-majority city once struck by U.S. reprisals and temporarily held by IS,” the following line appears: “Alongside Afghanistan, Iraq was the front line of the ‘war on terror’ that the United States waged after the September 2001 attacks.” Although the article uses quotation marks around “war on terror,” it does not note, for example, that there was no evidence linking Iraq to the perpetrators of 9.11, which could lead readers to associate Iraq with 9.11.

Internally displaced persons in Iraq (Photo: Mstyslav Chernov / Wikimedia Commons[CC BY-SA4.0])

This study highlights that Japanese media have continued to use the term “war on terror” without questioning its validity, even though the very government that coined it has ceased to use it. This suggests that Japanese media still tend to view the wars waged by the United States after 9.11 as being “to fight terrorism.”

Conclusion

By analyzing coverage around the 20th anniversary of the 9.11 attacks, we found that current reporting on 9.11 is skewed in both region and content, and fails to convey important related information. In many of the articles examined, there was also a tendency to accept at face value information issued by the U.S. government, a party to the conflict, and to pass it straight on to readers. Moreover, as seen in the frequent use of the term “war on terror,” the media continues to use language that does not reflect the facts. Continued biased reporting of this kind not only reinforces readers’ perception that U.S. wars were “to fight terrorism,” but may also deprive them of opportunities to view war critically and to question its legitimacy.

※1 Weapons such as anti-personnel landmines and poison gas are considered “inhumane weapons” because their indiscriminate effects cause significant civilian harm or inflict unnecessary suffering such as lasting aftereffects. The Obama administration promoted “humane war” by eschewing these “inhumane weapons,” thereby advancing the use of drones. In reality, however, drone strikes have caused significant civilian casualties.

※2 Period: 2021/1/1–2021/12/31. All pages of the Tokyo morning and evening editions and the Tokyo regional edition were included. The search terms were “9・11 or 9.11 or simultaneous terrorist attacks,” and from the resulting hits, articles relevant to 9.11 were extracted.

※3 We tallied using the method of taking one article as 1 and dividing by the number of related countries (e.g., if an article related to both the United States and Japan, each was counted as 0.5).

※4 If an article described both U.S. military and civilian losses, each was counted as 0.5.

※5 Including “war on terror,” “fight against terrorism,” “counterterrorism war,” “counterterrorism,” “counterterrorism front,” etc.

Writer: Seiya Iwata

Graphics: Mayuko Hanafusa

すごくおもしろかったです。9.11のビル倒壊の謎や、イラクとの外交の裏側についてはほとんど知りませんでした。日本のメディアはやはりアメリカに忖度しているのでしょうか