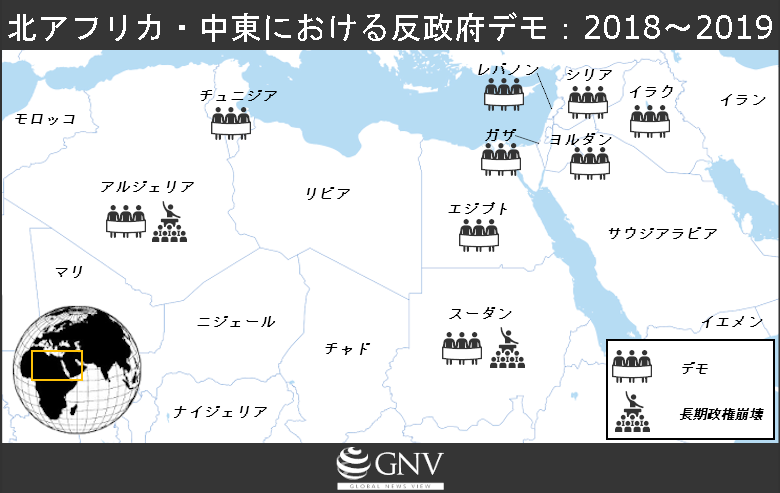

From 2018 to 2019, countries that had once experienced the Arab Spring were on the verge of revolution again. Behind this was the fact that public dissatisfaction with authoritarian regimes in North African and Middle Eastern countries had reached a breaking point. In Sudan and Algeria, popular discontent led to the overthrow of long-standing regimes. Large-scale demonstrations also broke out in other countries. As streets filled with people calling for regime change, the scenes evoked memories of the original “Arab Spring,” and this series of revolutionary movements came to be called the “Second Arab Spring” (※1).

As with the first Arab Spring, the phenomenon of citizens rising up against a backdrop of unemployment, high prices, and corruption; nationwide demonstrations toppling long-standing authoritarian regimes; and the movement spreading across borders was a momentous development that would shape subsequent world affairs. Did Japanese media detect and convey this trend? How much, and in what way, did they report on what is being called the Second Arab Spring? This article analyzes the nature of that coverage (※2), focusing on Japanese media reporting on North Africa.

People protesting on a train bound for Atbara, Sudan (Osama Elfaki / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

目次

The First and Second Arab Spring

The spark for the first Arab Spring was the self-immolation of a young man in Tunisia in December 2010 in protest against police corruption. This incident triggered nationwide protests demanding regime change, and in January 2011 the regime of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali collapsed. Notably, this wave of protests spread across borders to countries in the Middle East and North Africa. After the collapse in Tunisia, anti-regime demonstrations broke out in Egypt, and about a month later then-President Hosni Mubarak resigned and the regime fell. In response to such anti-government movements, regimes also collapsed in Libya and Yemen, and protests erupted in other countries including Algeria, Kuwait, Syria, Sudan, Bahrain, Jordan, and Morocco. Common to all these countries were long-standing authoritarian regimes and underlying issues such as economic inequality and political corruption that fueled public discontent. The simultaneous uprising of people across countries who shared similar hardships, and the spread of protests across the Middle East and North Africa, led observers to dub the phenomenon the Arab Spring, likening the long years of authoritarian rule to “winter.”

Around 2018, problems such as authoritarian rule, inequality, and corruption again came to the fore in North African countries, setting the stage for revolution. In December 2018, anger over inflation and surging prices of basic goods sparked anti-government protests in Sudan. Demonstrations demanding solutions to economic problems, democratization, and regime change then spread to countries including Algeria, Iraq, Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon. From January to April 2019, large-scale anti-government protests continued in Sudan and Algeria, leading to the collapse of long-standing regimes. Even in countries like Egypt and Tunisia, which had succeeded in toppling regimes during the first Arab Spring, protests broke out again over dissatisfaction with governments and their economic policies. In the background was the fact that, after the 2011 ousters, some countries reverted to authoritarian rule, while in others civilian governments failed to adequately address economic problems entrenched in their societies. Because this renewed wave of cross-border protests by people suffering under authoritarian regimes closely resembled the Arab Spring of 2011, the series of revolutionary movements from 2018 to 2019 came to be widely called the Second Arab Spring.

Here we focus on North Africa and briefly review the path to protest in four countries: Sudan and Algeria, where regimes were toppled, and Egypt and Tunisia, where demonstrations re-emerged despite regime change during the first Arab Spring in 2011.

Sudan was an authoritarian state led by President Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir, who seized power in a 1989 coup. During the first Arab Spring, protests also unfolded in Sudan. One factor behind the protests was that, following South Sudan’s secession in July 2011, the country’s oil reserves were drastically reduced, causing a shortage of foreign currency and severe inflation. In response, President Bashir announced that he would not run in the 2015 presidential election. Combined with the government’s harsh repression of the protests, the movement subsided without bringing down the regime. However, Bashir ultimately remained in office after 2015, and public grievances went unresolved. The immediate trigger for renewed protests came in December 2018, when the prices of bread and other essentials surged dramatically, directly hitting households already in economic distress. From December 2018 through March 2019, citizens continued large-scale demonstrations, and there were casualties due to repression by government forces. Ultimately, a military coup forced President Bashir to resign. However, the public fiercely opposed the idea that the coup leaders in the military would head a transitional government. In response, on August 17, 2019, it was formally decided to shift to joint civilian-military rule—short of full civilian government. This was only a provisional arrangement, and the outlook remained uncertain.

Sudan was an authoritarian state led by President Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir, who seized power in a 1989 coup. During the first Arab Spring, protests also unfolded in Sudan. One factor behind the protests was that, following South Sudan’s secession in July 2011, the country’s oil reserves were drastically reduced, causing a shortage of foreign currency and severe inflation. In response, President Bashir announced that he would not run in the 2015 presidential election. Combined with the government’s harsh repression of the protests, the movement subsided without bringing down the regime. However, Bashir ultimately remained in office after 2015, and public grievances went unresolved. The immediate trigger for renewed protests came in December 2018, when the prices of bread and other essentials surged dramatically, directly hitting households already in economic distress. From December 2018 through March 2019, citizens continued large-scale demonstrations, and there were casualties due to repression by government forces. Ultimately, a military coup forced President Bashir to resign. However, the public fiercely opposed the idea that the coup leaders in the military would head a transitional government. In response, on August 17, 2019, it was formally decided to shift to joint civilian-military rule—short of full civilian government. This was only a provisional arrangement, and the outlook remained uncertain.

Algeria gained independence in 1962, and under an authoritarian system continued to rely on oil. Economic instability led to the outbreak of the Algerian Civil War in 1991, claiming many civilian lives. Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who took office in 1999, brought the turmoil under control and set about rebuilding the country. Although a series of reconstruction policies garnered public support, dissatisfaction over political corruption and rising prices was growing. During the Arab Spring of 2011, protests broke out in Algeria in response to demonstrations in neighboring countries. However, because the government lifted the state of emergency that had banned demonstrations in major cities since 1992—a key public demand—and promised new economic policies, the protests subsided and the regime did not fall. From 2014 onward, though, President Bouteflika disappeared from public view due to hospitalization, while day-to-day governance was effectively carried out by his close aides and relatives. Nevertheless, when Bouteflika moved to amend the constitution so he could run for a fifth term, the public erupted in anger, leading to the massive protests of 2019. The 2019 demonstrations drew more than one million participants and spread across Algeria, making them impossible for the government to ignore. After protests began in earnest in February, Bouteflika announced on March 11 that he would not run in the next election, and on April 1 he resigned the presidency.

President Bouteflika addressing the UN General Assembly in 2009 (United Nation Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In Egypt, although the 2011 Arab Spring forced President Mubarak to step down, the administration of the newly elected President Mohamed Morsi ended in a coup after only one year. After a transitional government, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who led the coup, became president in 2014. However, President Sisi’s policies were even more repressive than Mubarak’s, and repeated corruption was criticized. In 2019, after construction contractor Mohamed Ali—who had close ties to the president—publicly alleged various corrupt acts involving the president and the military, demonstrations calling for the president’s resignation broke out in major cities across the country. The regime responded with harsh repression, arresting and detaining journalists and other opposition figures one after another, using tear gas and live ammunition to disperse protesters, and causing many casualties.

Tunisia transitioned to democracy after the first Arab Spring toppled its regime. However, even after the transfer to civilian rule, the country failed to find effective solutions to the economic problems inherited from the previous regime. The trigger for protests was a government decision in January 2018 to raise tax rates on social infrastructure such as gasoline and telecommunications. This directly impacted people’s lives and sparked demonstrations across the country.

Thus, from 2018 to 2019, citizen-led protests erupted across North African countries in response to severe political and economic problems, and long-standing regimes fell in Sudan and Algeria. From here, we analyze how Japanese media covered this Second Arab Spring, using Asahi Shimbun (※3) as a case study.

Coverage of Sudan

We first look at reporting on protests, political upheaval, and regime change in Sudan. Over 2018–2019, Asahi Shimbun published a total of 16 articles about Sudan, totaling 8,176 characters. The first anti-government protests in Sudan occurred on December 19, 2018. The government countered with tear gas and other means, resulting in many casualties. Asahi Shimbun reported this in a 585-character article on December 29, 2018. Citizen resistance continued from January through March 2019. On January 20, 2019, demonstrations broke out nationwide in Sudan, and according to reports by human rights groups, 40 people were killed by government repression. Similar protests occurred repeatedly across the country in February and March as well. However, during this January–March period, the only article about the protests in Sudan was a single 280-character piece on February 23, 2019.

People demonstrating to demand President Bashir’s resignation (Hind Mekki / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Sudan’s situation changed dramatically with the mass protests that began on April 6, 2019, followed by a military coup on the 11th that brought down the Bashir regime. This sequence of events—from the civil movement to the coup—has also been called the Sudanese Revolution. Yet after the February 23 article, there was no reporting on Sudan during March and early April—when the power struggle over the regime was most intense—and only on the day after the regime fell, April 12, did an article report that President Bashir had been ousted by a military coup. In April after the regime’s collapse, a total of eight articles covered citizens voicing opposition to the military government, and five articles mentioned Sudan from then until the decision in July to transfer from military to civilian rule. There was also one article in December 2019 as the presidential election period began. Thus, while there was a reasonable amount of reporting after the coup, during the crucial period from January to early April 2019—when the civil movement was expanding and the long-standing regime was toppled—Asahi Shimbun mentioned Sudan only once, in a brief item on February 23.

Next, we consider how the coverage was framed. In the article of December 29, 2018, when the Sudan protests were first reported, it was noted that high prices lay behind the demonstrations. Coverage from April onward also touched on economic problems and the voices of citizens struggling in their daily lives, so the background to the protests was explained in the reporting. On the other hand, there was no mention of similar protests occurring around the same time in neighboring countries for similar reasons, nor of any connection to the first Arab Spring.

Former President Bashir attending a conference in Sudan (Paul Kagame / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Coverage of Algeria

How was Algeria—where protests resulted in regime change—covered? During the year of 2019, when a wave of demonstrations unfolded, Asahi Shimbun ran a total of 12 articles on Algerian politics, totaling 4,609 characters. All were about the demonstrations or the presidential election. The first anti-government protests in Algeria occurred on February 12, 2019. A demonstration on the 22nd of that month drew an estimated 800,000 people, making it extremely large. The following week the protests grew even bigger; the demonstration on March 1 reportedly drew an estimated one million participants. With these massive demonstrations continuing day after day, President Bouteflika, responding to the demands of the protesters, announced on March 11, 2019 that he would not run for a fifth term, and on April 1 he announced that he would resign before his term ended.

The timing of the coverage is noteworthy. Demonstrations with more than a million participants occurring in quick succession are rare globally. Considering that the 2011 Arab Spring also began with similar civil protests—and that similar demonstrations were occurring in places like Sudan—the news value should have been high. However, Asahi Shimbun did not report on the February anti-government protests at all, and only when it became clear on March 11 that the president would step aside did it cover Algeria, in a short 205-character piece. In other words, it ignored million-strong protests.

Demonstrations in Algeria during the “Second Arab Spring” (Fethi Hamlati / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Now for the substance of the reporting. The first March 11 report focused on the information that President Bouteflika, in the face of repeated demonstrations, had abandoned his bid for a fifth term. Although it mentioned that protests involving tens of thousands had continued, it did not delve into the background. The next mention of Algeria was an article on April 2 reporting only that Bouteflika had announced his resignation. Again, the focus was on the president rather than the citizens who kept raising their voices in protest. Across the coverage up to April, there was no mention of the economic problems, corruption, and other issues that underlay the protests. The next time Algeria was covered was about five months later, on September 17, 2019, in an article centered on the presidential election slated for December, which also included voices from the military and parts of the public. On December 12, 2019, ahead of the presidential election, a feature article looked back at the previous Bouteflika administration and the protests that toppled it; only here were the administration’s policies, corruption issues, and the voices of discontented citizens finally highlighted. Subsequent pieces on December 13, 15, and 19 reported on voting, the results, and the new president. Of all the 2019 articles concerning Algeria, only one focused in detail on the background of the protests and the voices of participating citizens; the rest concerned the president’s resignation and the subsequent election.

Judging from Asahi Shimbun’s 2019 coverage, the president’s exit received attention, but the underlying circumstances, the massive civil movement that forced his resignation, and the path that led there were covered only minimally. In the first Arab Spring, citizens suffering in their daily lives rose up to change the status quo. In the second Arab Spring, unresolved grievances spurred citizens to protest against presidents clinging to power, leading to resignations. There is continuity between the events of 2019 and those of the first Arab Spring in 2011, and reporting on Algeria’s role during the first Arab Spring would have deepened readers’ understanding. However, Asahi Shimbun did not mention the first Arab Spring. The historical movement in which citizens voiced long-standing grievances against authoritarian rule and toppled regimes with their own hands, and the way the demand for democratization crossed borders to become a major movement with broad impact on world affairs—these are points shared with the first Arab Spring. As with the first Arab Spring, the push to oust Algeria’s regime had the potential to affect neighboring countries and the world. Given the way this regime change was reported, it would be difficult for readers to gain a panoramic understanding of the wider North African context—including Algeria—and how events there could affect the world.

People demonstrating to demand President Bouteflika’s resignation (Amine Rock Hoovr / unsplash)

Coverage of other countries

Next, we look at neighboring countries where civic movements emerged during the same period, even though they did not culminate in regime change like Sudan and Algeria.

First is coverage of Egypt. In Egypt, multiple demonstrations took place in late September 2019. The number of participants was comparatively small, and the protests were on a smaller scale than those in Algeria and Sudan. Regarding Egyptian politics overall, there were 23 articles totaling 18,116 characters in 2018, and 17 articles totaling 8,307 characters in 2019. However, among these, only two articles addressed the 2019 protests: a 173-character piece on September 22 and a 502-character piece on September 29. The other articles covered topics such as the presidential election and the referendum on constitutional amendments. In terms of overall volume, coverage of Egypt—where no regime change occurred—was more extensive than coverage of Sudan and Algeria, even though revolutions against long-standing regimes were unfolding in those countries at the same time.

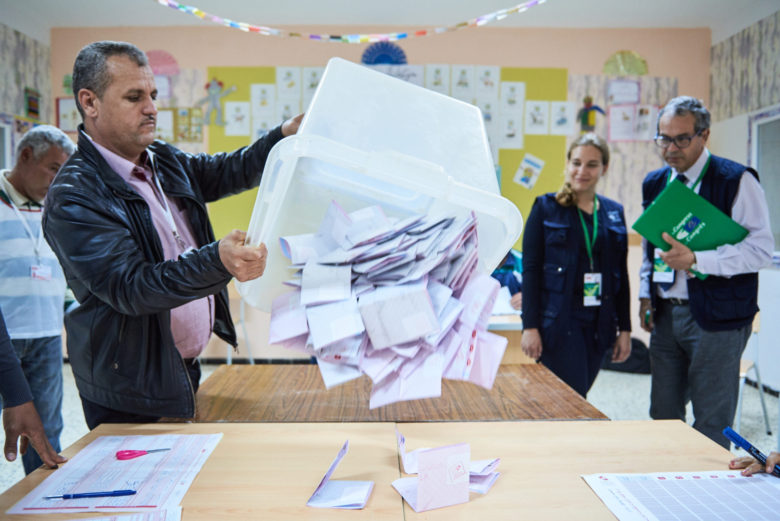

Next, we look at Tunisia. The first protests over surging prices for social infrastructure, such as utilities, occurred in January 2018 and continued for about a month. Although the exact number of participants is unknown, it was reported that 328 people were arrested in clashes with police between January 1 and 12, suggesting intense confrontations between demonstrators and the authorities. Protests continued for a month, occurring multiple times in multiple cities. Yet there was not a single article covering these demonstrations. In 2019, there were 10 articles about Tunisia, all of which concerned the presidential election.

Summary

We have analyzed coverage of four North African countries related to the series of events known as the Second Arab Spring. In the reporting on all four, even as civic movements and revolutions unfolded, little was reported until a president resigned, and the background was not sufficiently explained. Even between Algeria and Sudan—both of which saw regimes toppled by protests during the same period—coverage of Sudan was more extensive in both quantity and quality. One possible reason is that, whereas the transition to civilian rule after Bouteflika’s resignation proceeded relatively smoothly in Algeria, in Sudan the military seized power after the regime fell, causing further turmoil. Meanwhile, compared with Algeria and Sudan, the protests in Egypt were smaller and did not lead to major political upheaval, yet coverage of Egyptian politics was generally more prominent. Egypt’s popularity as a tourist destination in Japan, its large population, and the presence of an Asahi Shimbun bureau there likely played a role.

Scenes from the municipal council elections held in Tunisia in May 2018 (Congress of local and regional authorities / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

Overall, the series of revolutionary movements sometimes called the Second Arab Spring was not presented as a cross-border dynamic, but was instead viewed largely through the lens of domestic political change in individual countries. As with the first Arab Spring, revolutions and political upheavals do not remain confined within national borders; they spread to other countries facing similar conditions. In today’s highly globalized world, change sparked by a single event can have knock-on effects elsewhere. Even if a movement does not lead to regime change, citizens speaking out about the hardship of daily life and their concerns about government is, in itself, something worthy of attention. Considering that the first Arab Spring led to developments such as democratization in Tunisia, the war in Syria, and even the rise of the Islamic State, it was entirely foreseeable that the second Arab Spring could bring new changes to the region and the world. In fact, North Africa has already been transformed by this series of events. The world is interconnected, with mutual influences. It may be that this perspective is lacking in Japanese coverage.

※1 In this article, we refer to the period from December 2010 to December 2012 as the first Arab Spring, and the developments from January 2018 onward as the second Arab Spring.

※2 For coverage of the Middle East, see: “A Turbulent Middle East (2011–2020): How Was It Reported?”

※3 Using Asahi Shimbun’s “Kikuzo II Visual” database, we analyzed articles published in 2018 and 2019 in the national edition and the Tokyo local edition where the headline and text contained the names Algeria, Egypt, Sudan, or Tunisia, and where the country in question was the main subject of the article.

Writer: Takumi Kuriyama

Graphics: Minami Ono

国によって報道量に差が生まれてしまうという現実を知り、つらく感じました。