On 2022/4/16, at the Perkoa mine in Burkina Faso in West Africa, 8 mine workers were trapped by flooding and, after just under two months of searching, an incident occurred in which all 8 were found dead. They had been unable to reach a refuge chamber inside the mine. In fact, the Perkoa mine where this incident occurred is operated by the Canadian mining company Trevali Mining. The company is facing severe criticism for its emergency response and neglect of safety measures.

Today, Canadian mining companies operate many mines around the world. At the same time, they face a range of problems. This article explores the issues surrounding such Canadian mining companies.

Gold is Canada’s top mineral by production (Photo: hamiltonleen / [ Pixabay License ])

目次

Canada’s mining industry

Canada is a country rich in natural resources, which accounted for 11.5% of nominal GDP in 2020. As a result, mining is a key domestic industry, and the value of mineral production in Canada in 2020 was 34.3 billion USD (※1). Looking at the top five minerals by production value in Canada, they are gold, iron ore, potash (potassium carbonate), copper, and coal. The production value of gold is more than three times that of iron ore in second place; in fact, among the top 40 Canadian mining companies by revenue, 23 operate gold mines. Globally, Canada ranks 5th in gold production value.

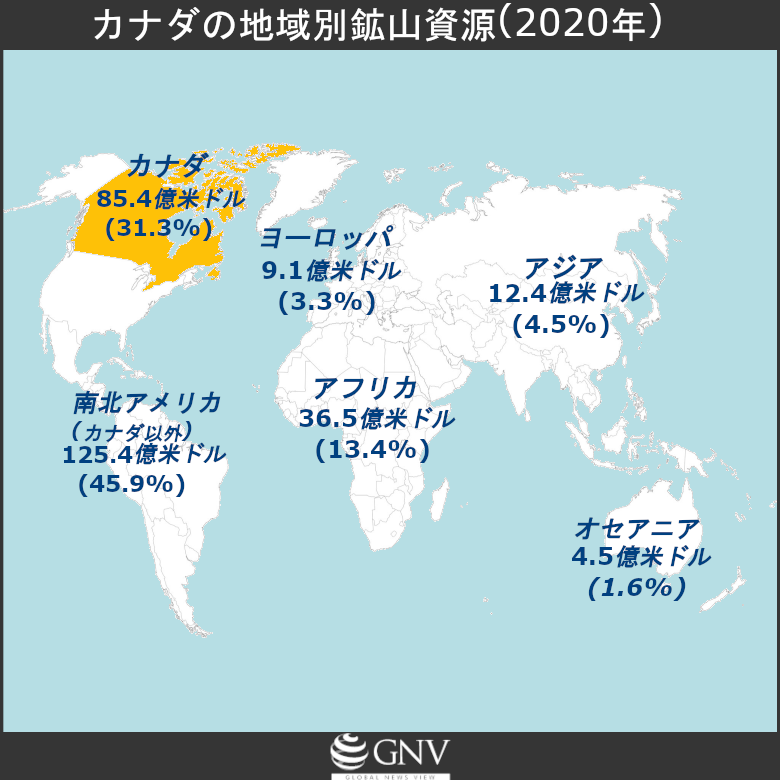

Next, let’s look at Canadian mining companies around the world. Canadian mining companies’ global expansion is remarkable: companies headquartered in Canada account for about 75% of the world’s mining companies (※2). As of 2020, they are active in mines in 97 countries, and of total Canadian mining assets of 273.4 billion USD, overseas mining assets account for 188.2 billion USD. In other words, roughly 70% of the profits earned by Canadian mining companies come from abroad. By region, the Americas excluding Canada account for the most at 125.4 billion USD, followed by Africa at 36.5 billion USD. By country, the top 3 are the United States (21%), Chile (11%), and Panama (8%).

Created based on data from Natural Resources Canada

Why, then, do Canadian mining companies dominate so much of the global mining industry? One reason is that Canada’s laws and policies are highly beneficial to mining companies. Not only are regulations lax and systems of corporate oversight absent, there are also many tax incentives. As a result, not only do domestic companies become powerful, but many firms from abroad gather as well. This concentration brings together and improves exploration and extraction technologies, creating synergies; consequently, Canada has become a hub for the world’s mining companies. In this way, Canada has not only developed its mining industry by leveraging abundant domestic natural resources, but has also amassed enormous wealth by controlling mines and mineral production around the world, accounting for a large share of the global mining industry.

However, alongside this global expansion, mining companies have created several problems as the price of maximizing their own profits. The major issues facing Canadian mining companies can be grouped into three: the extraction of wealth, human rights abuses against workers, and environmental pollution.

Exploitation of wealth

The first is the extraction of wealth. As noted above, Canada operates many mines across the world. Why do these countries accept Canadian mining companies in the first place? Especially in low-income countries, constraints in capital and technology limit what resources can be extracted. By accepting foreign companies rich in capital and technology, the host country receives a portion of the wealth from the mined resources (called royalties) and corporate taxes, allowing both the foreign mining company and the host country to benefit. However, in the mining industry, these royalties are often set low, and in some cases even the taxes that should be paid are not paid. In other words, in reality, sufficient money does not flow into the host country; foreign mining companies often monopolize the profits, leading to capital flight from resource-holding countries to the foreign companies operating the mines.

Rosh Pinah mine in Namibia (operated by Trevali Mining) (Photo: Hp.Baumeler / Wikimedia Commons [ CC BY-SA 4.0 ])

Here, let us briefly describe the mechanism of illicit financial flows. Illicit financial flows were covered in a past GNV article. Illicit financial flows refer to wealth flowing abroad by illegitimate means rather than remaining where it should; in trade, they often occur from the point of mineral extraction through export. When operating abroad, companies use illegal methods to reduce the taxes owed to the host country. A common method is to overstate the costs of extraction/production or understate the price of mineral resources at export, thereby making profits appear lower than they are and reducing taxes. Tax havens are often used to conceal such price manipulation. Tax havens were also covered in a past GNV article.

For example, First Quantum Minerals (FQM), a mining company headquartered in Canada, uses intra-group loans to raise funds for mining activities, and through high interest rates transfers profits earned from mine operations and uses tax havens to conduct price manipulation, thereby lowering its tax liabilities.

Furthermore, there are cases where taxes are not paid to the Canadian government as well as to host governments. The Canadian mining company Silver Wheaton provides financing to mining companies through its wholly owned subsidiary Silver Wheaton (Cayman) Inc. in the tax-free Cayman Islands, and in return receives mineral resources to earn profits. Even though the substantive activities of this subsidiary are in Canada, because it operates through a Cayman Islands paper company, Wheaton does not pay taxes in Canada.

There are also cases of tax avoidance by legal means. For example, the Canadian engineering firm SNC-Lavalin built a processing facility for a mine in Senegal in 2012 through its subsidiary SNC-Lavalin Mauritius Inc. This is because a treaty concluded in 2004 between Senegal and Mauritius allows significant tax reductions by legal means. The company claims it did not use the Mauritius subsidiary for the purpose of tax reduction, but the truth is unclear.

Human rights abuses against workers

The second issue is human rights abuses against workers. As noted above, Canadian mining companies often monopolize profits that should be returned to the host country in order to maximize their own gains. At the same time, they also engage in excessive cost cutting to increase profits. They frequently take advantage of lax labor conditions set by host governments regarding safety measures and compensation to drastically reduce costs for safe operations and labor.

For example, the Perkoa mine in Burkina Faso mentioned at the beginning is one case where neglect of safety measures led to an accident. The factor that left 8 people trapped inside the mine was flooding caused by heavy rains, but it is believed that the use of dynamite a few days prior contributed to the disaster. The use of dynamite had weakened the ground in the mine, making it prone to collapse. Considering the circumstances, the occurrence of a disaster should have been anticipated, yet the mining company appears to have failed to prepare for it. This suggests a lack of consideration for safety.

Workers at the Kansanshi mine in Zambia (operated by FQM) (Photo: Utenriksdepartementet UD / Flickr [ CC BY-SA 2.0 ]))

Another incident stemming from low pay and forced labor concerns working conditions at the Bisha mine in Eritrea. The Canadian mining company Nevsun Resources is said to have exploited the prevalence of forced labor under Eritrea’s conscription system to use workers like slaves. Local workers claim they were paid about 30 USD per month, forced to work long hours in terrible conditions, and denied leave even when they became ill.

There have been multiple reports of local workers being forced to work side by side with danger or in conditions that could by no means be considered humane, as a result of cost-cutting measures undertaken by mining companies for their own profit.

Conflicts between residents near mines and mining companies also arise when companies develop and operate mines. In such cases, local governments and police sometimes take excessive measures to protect mining company activities. For example, at the North Mara mine in Tanzania, it was revealed in 2016 that over several years local police killed a total of 65 residents and injured another 270. Several deaths were also said to have been caused by the mine’s private security guards. The cause was sporadic clashes between people entering the mine to scavenge tiny amounts of gold from mine waste and the mine police who sought to keep them out. The North Mara mine is operated by a subsidiary of Canada’s Barrick Gold Corporation, and the company is said to have been complicit in police actions. In response, the Canadian government and the company state that the incident was the result of a long-running conflict between the mine and local residents trespassing illegally, and they deny involvement in abuses.

At mines in Latin America, many killings and abuses have been carried out against opponents of mine development. According to the Justice and Corporate Accountability Project (JCAP), between 2000 and 2015, at mines operated by Canadian mining companies in 14 Latin American countries, 44 deaths and 403 injuries were confirmed. These numbers are only the confirmed cases and are said to be the tip of the iceberg. In these incidents, reports indicate that 28 Canadian companies were involved. Canadian companies are not directly involved in every incident; sometimes they collude with the parties who carried out the killings and injuries, or they create conditions that give rise to human rights abuses. Canadian companies appear to have reported only 24.2% of the deaths and 12.3% of the injuries.

Environmental pollution in surrounding areas

The third issue is environmental pollution. Through extraction projects, Canadian mining companies are causing serious environmental problems in host countries. For example, in Latin America, environmental problems have arisen near the Lagunas Norte mine in northern Peru. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) reported that the mine is causing severe contamination at the headwaters of nearby rivers, affecting surrounding crops and ranches. In response, Barrick Gold, the Canadian company that operates the mine, claims the contamination is due to naturally occurring mineralization in the area and is unrelated to its mine.

Tasiast open-pit mine in Mauritania (operated by Kinross Gold) (Photo: Kinross Gold Corporation / Flickr [ CC BY-SA 2.0])

The Marlin mine in Guatemala, operated by the Canadian company Goldcorp, has also been reported to have caused large-scale water pollution. Heavy metals such as iron and aluminum have been found in nearby rivers, and it has been found that the urine of residents living near the rivers contains higher-than-usual levels of such heavy metals.

In Africa as well, extraction projects and plans are putting the environment at risk. About 44% of major metal mines in Africa are located within protected areas or within 10km of them, and there is concern about direct impacts within protected areas.

Past GNV articles have also addressed environmental pollution caused by mines.

Background to the problem

What lies behind these problems faced by Canadian mining companies? One factor is legal issues in the bilateral relationship between Canada and the countries where mines are located. First, from Canada’s side: although Canada has many companies operating overseas and the Canadian government provides extensive protection for mining companies operating domestically and abroad, it does not have adequate laws to regulate Canadian companies’ human rights abuses and environmental destruction overseas. There are also no sufficient laws requiring companies to adequately explain such problems that occur abroad.

Next, consider the legal characteristics of the countries where mining takes place. Many of the countries where Canadian mining companies operate do not have well-established democratic systems, and the rule of law is relatively weak with respect to issues such as human rights and corruption. There is also often a lack of accountability. Due to these defects in the legal systems of both Canada and the countries that accept Canadian mining companies, Canadian mining companies cause numerous problems, and the Canadian government turns a blind eye to them.

Another issue is the power imbalance between the Canadian government and the governments of countries that host mines. Most of the countries where Canadian companies operate mines have lower incomes than Canada, creating an unequal inter-state power relationship. Thanks to this imbalance, not only Canadian companies but also the Canadian government can profit economically. Consequently, the Canadian government does not work to establish binding international treaties to protect the environment, labor conditions, and the interests of local communities, nor does it impose strong regulations on Canadian companies when they operate overseas. Host governments likewise do not impose strong regulations on Canadian mining companies. One reason is the prevalence of corruption and bribery in the natural resources sector. Resource revenues are easy for government officials to control and monopolize. Especially in resource-dependent economies, the economic costs of accepting corruption are small, and officials themselves may benefit from bribes. For their own benefit, they act to increase the profits of Canadian mining companies.

Round Mountain gold mine in Nevada (operated by Kinross Gold) (Photo: Uncle Kick-Kick / Wikimedia Commons [ CC BY-SA 2.0 ])

In addition, Canada has concluded treaties called Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreements (FIPA) with many countries around the world. Under these agreements, when companies operate in a signatory country and that country enacts policies that hinder the pursuit of profits, companies are given the right to sue the government. As a result, even if a host government where a Canadian company operates a mine makes democratic decisions on economic or environmental policies to address the problems mentioned above, Canadian companies and investors can challenge them in court. Although the agreements grant the same rights to both countries, because there are almost no companies from African countries investing in Canada, in reality they are unfair treaties. In this way, FIPA is designed to protect Canadian mining companies.

Toward solutions

As we have seen, Canadian mining companies cause numerous problems. Are these issues moving toward resolution? One improvement is cross-border legal measures. The Mining Association of Canada, an organization that influences policy in Canada’s mining sector, claims that Canadian courts hearing cases involving foreign plaintiffs such as mine workers and Canadian companies is a step forward in terms of transparency and clarity for mining companies. In fact, cases in which Canadian companies are held responsible for human rights problems at mines they operate have increased.

For example, regarding forced labor at mines in Eritrea described above, three Eritrean workers filed suit in Canadian court in 2014. This was the first case in which a human rights issue at a foreign mine was brought before a Canadian court. As a result, Nevsun’s denial of abuse and its argument that Eritrea should be the forum were rejected, and the Eritrean plaintiffs and the Canadian company reached a settlement.

In another case, in 2007, at the Phoenix mine in Guatemala, in relation to mass rapes allegedly committed by local police, soldiers, and security guards as one of the means to forcibly evict residents for mining operations by the Canadian company Hudbay Minerals, the company was sued in Canadian court in 2011 by 11 Guatemalan women. In 2013, the court denied Hudbay’s motion to dismiss, securing a victory for the Guatemalan women. However, for individuals suffering human rights abuses to bring cases to faraway Canadian courts and sue mining companies with enormous resources is extremely difficult, and for many victims nearly impossible. Winning in court is likely to remain the exception.

President Medina of the Dominican Republic being received by a vice president of Barrick Gold and Canada’s ambassador (Photo: Gobierno Danilo Medina / Flickr [ CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The Mining Association of Canada also claims that more countries are undertaking proactive corporate efforts to bring transparency to mining operations.

However, although individual human rights cases are sometimes brought and individual companies are beginning to pursue improvements, it is often difficult for individuals to bring human rights cases to Canadian courts, and corporate efforts remain at the individual company level and are not binding. Moreover, the problems caused by mining companies are wide-ranging—capital flight, human rights abuses, environmental issues—making comprehensive measures at the individual company level difficult. Therefore, it is urgent to seek comprehensive, fundamental solutions: reform legal systems in Canada, in resource-holding countries, and at the international level to strengthen corporate accountability and penalties for violations, and develop not only remedies but also preventive measures.

※1 All amounts are shown in USD. Where the references are in Canadian dollars, they were converted to USD based on the 2020 average exchange rate 1CAD=0.7462 USD.

※2 S&P Global Market Intelligence offers the view that the share is about half.

Writer: Yuna Nakahigashi

Graphics: Yudai Sekiguchi

0 Comments