“Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, from those who are cold and are not clothed. In this world that is armed, it is not only money that is being consumed. It is the sweat of the laborer, the genius of the scientist, the hopes of the children.”

These are not the words of experts or activists calling for world peace. They were spoken by Dwight D. Eisenhower, former U.S. Army Chief of Staff who became U.S. president in 1953, in his remarks. In his 1961 farewell address, he warned of the need to be vigilant about the close ties among the U.S. administration, Congress, the Department of Defense, and the arms industry, which could have a profound impact on U.S. domestic and foreign policy. He called this relationship the “military-industrial complex.”

Eisenhower also had a side that saw him, as both a soldier and a president, directing what could be called the very military-industrial complex. Yet his warning carries a certain persuasiveness precisely because he himself had played such roles. More than 60 years have passed since the term “military-industrial complex” came into use; how has its reality changed today?

Today’s military-industrial complex has swelled, both in the Department of Defense budget and in the size of the arms industry, arguably exceeding the concerns Eisenhower raised. It consists of organizations and individuals who profit from armaments, the arms trade, and war. While many countries around the world are increasing their military and defense budgets, the mechanism of the military-industrial complex lies behind this. In Japan, however, the term “military-industrial complex” is not widely used. Reporting, which plays a major role in shaping public opinion, can be seen as one of the reasons. This article therefore outlines the reality of the military-industrial complex and then examines how it is reported in Japan.

U.S. military personnel showcasing an F-35 fighter (United States) (Photo: U.S. Navy / GetArchive [Public domain])

目次

Overview of the military-industrial complex

Even before the term “military-industrial complex” was used, Smedley Butler, a former U.S. Marine Corps major general, sounded the alarm about the profits generated by war. Butler fought in U.S. wars for many years in Latin America, China, and elsewhere, but joined the anti-war movement after retiring. In a magazine published in 1935, he said, “I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high-class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and for the bankers. I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism,” and in the same year he published the book War Is a Racket (War Is A Racket).

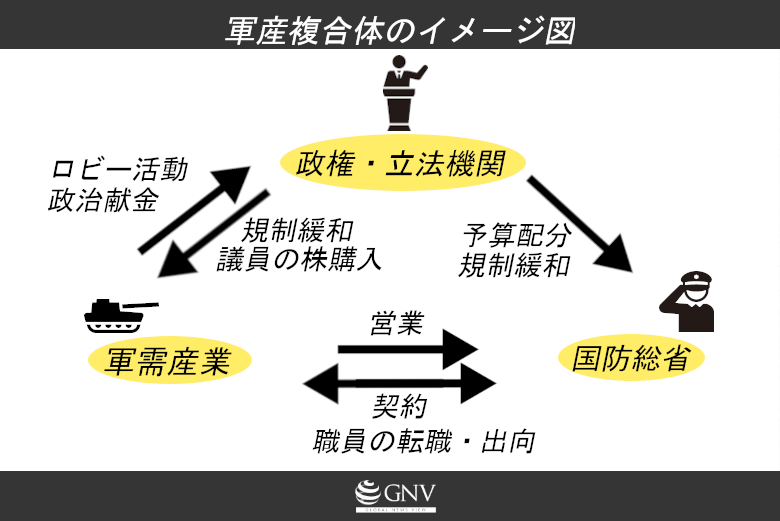

After Eisenhower’s “military-industrial complex” remarks, the relationship among the arms industry, the Department of Defense, and the executive and legislative branches came to be depicted in the U.S. as an “iron triangle.” The iron triangle works as follows. Private companies (the arms industry) that supply weapons and other equipment and services to the Department of Defense engage in sales activities—such as appealing to the Pentagon the necessity of certain weapons—in order to sell more. Meanwhile, the executive and legislative branches determine the Pentagon’s budget allocation and set regulations on the manufacture, use, and export of weapons. To increase the budget allocated to the Pentagon and to loosen regulations, the arms industry makes political donations and engages in lobbying aimed at people in the executive and legislative branches. In the U.S., it has been shown that lawmakers who voted for increases in the Pentagon’s budget received far more political contributions from the arms industry than those who voted against them.

The mechanism of the military-industrial complex is not confined to domestic U.S. political and economic issues. The arms industry also develops through arms imports and exports and through military actions and military support to other countries. It is therefore common for a country’s own government to join in the arms industry’s sales efforts.

At the individual level, there are also connections among actors in the military-industrial complex. Active-duty personnel may be seconded between the arms industry and the Department of Defense, and retired military officers often take jobs in the arms industry. In the U.S., there are data indicating that 80% of generals move into the arms industry after retirement. Some, like Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, have experience working in all three corners of the iron triangle. Austin came from the Army, worked for a defense company after retiring, and in 2021 joined the administration as Secretary of Defense. Many U.S. lawmakers also hold shares in defense companies. When Congress decides to increase defense spending, expand arms exports, or undertake military action, defense stocks are likely to rise; when they do, lawmakers who hold those stocks profit at a personal level.

The concept of the military-industrial complex has most often been applied to the U.S., where defense spending and the scale of the arms industry are overwhelmingly large, but it can be applied to any country that has an arms industry. In China, now second in the world in defense spending, the rise of a military-industrial complex was noted more than a decade ago. In recent years, analyses of the European Union’s military-industrial complex have become frequent. In Europe as well, Russia’s military-industrial complex, which declined after the Cold War, has shown renewed growth in recent years. Israel receives extensive military support from the U.S. and is closely tied to the U.S. military-industrial complex, but it also has its own military-industrial complex that has significantly developed domestically. In Japan as well, there have been reports of stock holdings in defense companies by Diet members and their associates, and of political donations to the ruling party from the arms industry being reported.

An expanded military-industrial complex: MICIMATT

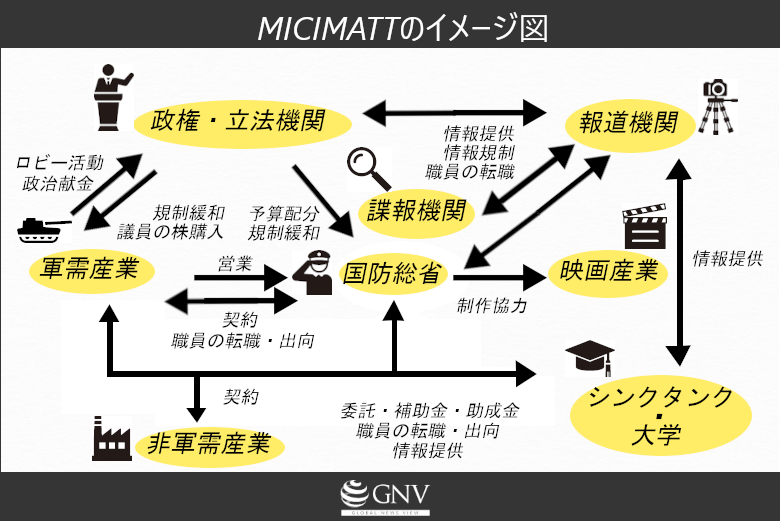

The military-industrial complex is not limited to the close ties among the executive and legislative branches, the Department of Defense, and the arms industry. Other actors are involved in decisions and actions surrounding defense spending, the arms trade, and war.

Among these, the presence of private companies outside the arms sector is particularly interesting. These companies do not directly manufacture weapons but are indirectly connected to the military-industrial complex. Examples include manufacturers of raw materials such as metals and producers of electronic components. Construction firms and service providers such as catering and cleaning are also involved in the building and operation of military bases. Furthermore, when the U.S. invades or occupies another country, construction and infrastructure companies take on the reconstruction of devastated cities and infrastructure after U.S. intervention. Financial institutions such as banks and investment funds can also profit greatly from war and the subsequent rebuilding. In this way, non-defense industries that benefit from the Pentagon and the arms industry are wide-ranging.

In countries where the military wields strong influence over politics, military-run companies can also advance into civilian sectors. In Egypt, military-run construction firms win many government contracts. In Pakistan, enterprises established for veterans produce fertilizers and even cornflakes.

Intelligence agencies and private entities handling information are also tied to the military-industrial complex. Companies involved with satellite technologies used for military purposes and information and communications technology firms dealing with cybersecurity are among them, as are consulting firms. Big Tech companies such as Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Oracle also take on Department of Defense projects.

The U.S. Secretary of Defense showing Amazon founder Jeff Bezos around the Pentagon (United States) (Photo: U.S. Secretary of Defense / Flickr [CC BY 2.0 Deed])

Researchers affiliated with universities may be involved in weapons technologies, and they also have ties to the military-industrial complex in government defense policy and in government-led counter-disinformation efforts. In addition, many foreign policy and security think tanks receive operating funds or grants from the arms industry and the Department of Defense. It is often pointed out that these think tanks frequently present positive views on increased defense spending and on government military interventions, and this is also said to be because they receive grants from the arms industry in the first place.

Relationships between news media and the military-industrial complex are also noted. Government bodies such as the executive branch, the Pentagon, and intelligence agencies are key sources for news media. As a result, media often repeat information and views issued by their own government without sufficient scrutiny. There are also cases where governments apply pressure or impose regulations on media output. In addition, former Pentagon and intelligence officials often appear as guests on news programs or even move into media jobs.

The entertainment industry, too, has ties to the military-industrial complex. Many Hollywood films about war receive cooperation from the Department of Defense at various levels. In return, there are reports that the Pentagon can make changes to scripts. Arms makers sometimes get involved in the entertainment industry as well. In 2023, U.S. weapons manufacturer General Dynamics sponsored an opera about U.S. military drone pilots.

Ray McGovern, a longtime veteran of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), dubbed the expanded military-industrial complex the “Military-Industrial-Congressional-Intelligence-Media-Academia-Think Tank complex” (MICIMATT) MICIMATT.

Problems arising from the military-industrial complex

There are many problems caused by the military-industrial complex. Wasteful spending of tax money is one of them. One of the drivers of the military-industrial complex is an arms industry that seeks constant expansion. Rather than curbing defense spending, governments show a tendency to purchase the most expensive weapons and equipment possible. Of course, it is difficult to objectively determine how much defense spending is necessary. However, across the world, there are numerous cases—reported in large numbers—in which low-quality or unnecessary weapons and equipment are traded at high prices.

In addition, job creation and expansion are often emphasized to justify increases in defense spending. However, there is evidence that allocating tax funds to social sectors such as education and healthcare creates more jobs than allocating them to defense.

Defense-related issues are treated as matters of national survival and are highly secretive. As a result, arms development and trade lack transparency, including in the amounts involved. This creates an environment ripe for wrongdoing and corruption in arms development and trade. It is also said that large bribes are often used in negotiations to conclude contracts. In fact, there are reports that arms deals account for 40% of corruption in world trade.

Moreover, a “threat” is needed in order to expand a country’s domestic arms industry. To be sure, threats to each nation do exist. But as part of the military-industrial complex, there are repeated observations that governments, defense ministries, think tanks, and media often exaggerate threats.

Furthermore, because both the use of force against other countries and the subsequent reconstruction work bring profits to domestic industries, the military-industrial complex can profit by both “creating” problems and by “solving” them. In recent years in Western countries, in addition to the traditional security domains of land, sea, air, space, and cyber, the “cognitive” domain has come to be seen as a new “battlespace.” Disinformation is among the targets in the cognitive domain, and an industry for countering disinformation is even growing. However, as revealed by internal information from Twitter known as the “Twitter Files,” initiatives undertaken in the name of countering disinformation also have the aspect of removing information inconvenient to state power from the information space. Some journalists call the network of actors involved in counter-disinformation the “censorship-industrial complex.”

The unreported military-industrial complex

As we have seen, the military-industrial complex influences increases in defense spending, arms races, interstate confrontation, and armed conflict. How, then, is the military-industrial complex covered in Japanese media? We analyzed 10 years (July 2013–June 2023) of reporting in the Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun that referenced the military-industrial complex (※1).

Fallujah, Iraq under U.S. airstrikes (2004) (Photo: Chaverri, LCPL Joel A / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

First, the term “military-industrial complex” appeared in 26 Mainichi articles, 17 Asahi articles, and 5 Yomiuri articles. On average, that is about twice a year in the Mainichi and once every two years in the Yomiuri, which is a small volume of coverage relative to the scale of the military-industrial complex and the seriousness of the problems it causes.

Moreover, even if the term appears in an article, the content does not necessarily explain the mechanisms of the military-industrial complex in a way that promotes reader understanding. In the Yomiuri, four out of the five articles that mentioned the military-industrial complex used the term merely to refer to Russia’s arms industry, without explaining the mechanism or the relationships among the actors. In the Asahi, eight out of seventeen articles concerned Russia’s and China’s arms industries or other countries’ sanctions on them. Other articles used the term to introduce the military-industrial complex as a mechanism or to describe relationships among the actors, but most did not delve deeply into its realities. The only piece that addressed problems created by the military-industrial complex was an article in January 2023 (January 6, 2023), an interview with Steven Leeper, former chair of the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, discussing the U.S. nuclear weapons modernization plan.

A few of the Mainichi articles related to the military-industrial complex did touch on its mechanisms. For example, a 2013 article on the U.S. pointed out that, in addition to the traditional relationship between the arms industry and the government, intelligence agencies and private firms are also part of the military-industrial complex (※2). Other articles dealt with problems surrounding the production of the F-35 and political donations from the U.S. arms industry (※3), and with the military-industrial complex driving the U.S. nuclear weapons modernization plan (※4).

In both the Asahi and the Mainichi, there were articles that sharply criticized the relationship among the Pentagon, the arms industry, and Congress. However, none of the newspapers ran articles that made the military-industrial complex the central theme of the entire piece, and the aforementioned Asahi and Mainichi coverage remained limited to fragmentary glimpses of the problem. Meanwhile, in the Yomiuri, we found no articles that took a critical view of the military-industrial complex. One article (※5) touched on the government and the military-industrial complex, introducing former U.S. President Donald Trump’s handling of his relationship with it.

The U.K. Secretary of State for Defence visiting a weapons trade show held in Japan (DSEI Japan 2023) (Photo: UK Government / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed])

Japanese reporting on the defense industry

Although the term “military-industrial complex” itself is not used, many articles in each paper touch on relationships among actors that constitute various countries’ military-industrial complexes and on the problems therein. We therefore expanded the concept from “military-industrial complex” to “defense industry” and analyzed 10 years (July 2013–June 2023) of coverage in each paper (※6).

Interestingly, compared to the volume of coverage referencing the military-industrial complex, mentions of the defense industry increased significantly. While the Yomiuri referred to the “military-industrial complex” only five times over 10 years, we found 132 articles that mentioned the “defense industry” (※7).

The majority of these articles dealt with interstate transactions and sanctions or other regulations surrounding the arms trade, or with the growth and trends in various countries’ defense industries. Examples include pieces on “military-civil fusion” in China’s defense industry (※8), and on debates over Swiss arms exports to Ukraine (※9). Following the Japanese government’s 2014 Cabinet decision to adopt new rules to replace the Three Principles on Arms Exports, many Yomiuri articles took a positive view of Japan’s arms exports as a business opportunity (※10). On the other hand, only one article viewed as problematic the improper billing of the Defense Ministry by multiple Japanese weapons manufacturers (※11).

We also examined which countries were the subjects of the 132 Yomiuri articles that mentioned the defense industry (※12). The country most frequently referenced was Russia, accounting for 24% of the articles. Second was China (17%), third the U.S. (15%), and fourth Ukraine (13%). Western European countries combined accounted for about 11%. In global military spending, the U.S. accounts for 39%, China 13%, and Russia 3.9% of the total. In global arms sales, U.S. companies account for 51% of sales by value. Despite the U.S.’s overwhelming presence in both military spending and arms sales, the Yomiuri focuses more on Russia’s and China’s defense industries than on the U.S. defense industry.

A U.S. aircraft carrier built by Northrop Grumman (Photo: U.S. Navy / Picryl [Public domain])

Among the three papers, the Mainichi showed the greatest interest in and the most critical stance toward the military-industrial complex and the defense industry. The number of Mainichi articles that referenced the defense industry (196) exceeded those in the Asahi (149) and Yomiuri (132). Among them were a small number of articles that linked specific events or government decisions to the problems of the military-industrial complex. For example, a 2023 article on drones stated that “while Russia’s ‘invasion’ of Ukraine continues to exact a heavy toll, it is a cold fact that it has become a major business opportunity for defense firms around the world” (※13). There were also articles critical of Japan’s arms exports (※14). On the other hand, a lengthy 2017 article on increases in the U.S. defense budget made little mention of the defense industry and presented only the positive claims that it would stimulate the industry and create jobs (※15).

Some Asahi articles that mentioned the defense industry also contained critical content pointing out problems in the relationship between the defense industry and government. For example, a 2013 editorial on the Three Principles on Arms Exports said, “Looking at the global arms trade, one often sees cases in which defense firms bribe senior government officials to get them to buy unnecessary weapons” (※16). However, like the other two papers, the Asahi rarely highlighted problems in the defense industry, and even when it did, the content often lacked specificity. For instance, over a 10-year period, only three Asahi articles mentioned lobbying or political donations by the global arms industry, and just one of them used data (※17). Notably, at least with respect to the U.S. arms industry, data on lobbying and political donations are not difficult to obtain.

Coverage of the Russia-Ukraine war and the military-industrial complex

GNV has previously pointed out that Japanese media tend to report in ways that align with power, and that this contributes to bias in Japan’s international reporting. One background factor is that governments are the primary sources for news organizations; another is a tendency to support the policies and positions of the Japanese government and its ally, the U.S. government, in foreign policy.

These tendencies and characteristics of Japanese media are evident in their coverage of the Russia-Ukraine war. It has been one of the U.S. goals to weaken Russia through the war, and it has also been reported that Washington has obstructed ceasefire talks between Russia and Ukraine. The U.S. encouraged Ukraine’s counteroffensive against Russia in June 2023 and provided large-scale military assistance. However, views within the U.S. government as early as February of that year held that the counteroffensive was unlikely to deliver results; there was a gap between those internal concerns and actual actions. As of November, months after the counteroffensive began, Ukraine still has not achieved significant gains.

Armored personnel carriers being manufactured in a Russian factory (Photo: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0 Deed])

Japanese media have paid relatively little attention to moves toward a ceasefire or peace in the Russia-Ukraine war. Even after it became clear that the Ukrainian counteroffensive launched in June 2023 was unlikely to succeed, most Japanese outlets continued to support military aid for the counteroffensive and expressed expectations that such support would lead to large territorial gains. For example, a Yomiuri editorial on September 21, 2023 argued, “The Ukrainian military has broken through Russian defensive lines in some areas and regained territory, but the results of the counteroffensive are still limited. It is essential that the U.S. and Europe continue and expand their military support.” Television news analysis programs were similar. For instance, Fuji TV’s Prime News on July 24, 2023 took up the theme “Analyzing the keys to a breakthrough for the Ukrainian military” and analyzed what would be needed for Ukraine’s counteroffensive to succeed.

Behind Japanese media coverage that encourages proactive military support for Ukraine lies the influence of sources affiliated with the military-industrial complex, who serve as primary information providers. For example, many of the experts who appeared as guests on the Prime News program mentioned above were affiliated with the National Institute for Defense Studies and were former members of the Ground Self-Defense Force. Among the latter, some currently serve as advisers to companies in the “defense industry” (※18). There are also former Self-Defense Forces officials who serve as strategic advisors or consultants to “defense industry” companies and who frequently share their views on the Russia-Ukraine war through newspapers and television programs. When these experts appear in the media, they are almost always introduced only as former Self-Defense Forces officials; their current positions are rarely disclosed.

Conclusion

From the above, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that Japanese media have downplayed the problems brought about by the military-industrial complex. It is difficult to derive from media coverage the answers to questions such as why defense spending is increasing around the world, why interstate confrontation is deepening, and why armed conflicts are becoming protracted. The immense military-industrial complexes lurking in various countries offer one important clue.

As the world moves toward military build-up, Eisenhower’s words introduced at the beginning may serve as an important reminder.

※1 We used each paper’s database—Asahi Shimbun Cross Search (Asahi Shimbun), Maisaku (Mainichi Shimbun), and Yomidas Rekishikan (Yomiuri Shimbun). We selected the main papers of each company and targeted the morning and evening editions. Mentions in reader submissions or non-article content were not included in the analysis.

※2 Mainichi Shimbun, “Dark Vision State America: / 4 Yellow Light for Classified Information Management; Reliance on Information Technology Expands Outsourcing,” July 27, 2013.

※3 Mainichi Shimbun, “Fuchi-so: F-35 and Politics = Takao Yamada,” December 4, 2017.

※4 Mainichi Shimbun, “United States: Strengthening Delivery Systems for Nuclear Warheads; NPR Clearly Lays Out Renewal of the Three Pillars: ICBMs, SSBNs, Strategic Bombers,” February 7, 2018.

※5 Yomiuri Shimbun, “Mr. Trump Criticizes Military Leaders; Support from Troops Wanes—Is It Anxiety?” September 22, 2020.

※6 Keywords used in the search: “軍需産業” (defense industry), “軍事産業” (military industry), “軍需企業” (defense company), “軍事企業” (military company).

※7 Changing the keyword to “防衛産業” (defense industry) yielded an additional 259 articles, but most dealt with Japan’s domestic industry and were not included in this analysis.

※8 Yomiuri Shimbun, “Promoting ‘Diplomacy of Values’: South Korea and Europe Strengthen Ties,” June 7, 2023.

※9 Yomiuri Shimbun, “Switzerland’s Shaken Neutrality: Pressure from Home and Abroad; Debate on ‘Weapons for Ukraine’,” June 6, 2023.

※10 Yomiuri Shimbun, “[Editorial] New Principles on Arms Exports: Emphasized from the Perspective of Security,” March 13, 2014.

※11 Yomiuri Shimbun, “Defense Industry PR Campaign: Each Company Opens Production Sites to the Public,” January 29, 2014.

※12 When a single article mentioned defense industries in multiple countries, we divided the count by the number of countries referenced.

※13 Mainichi Shimbun, “How the ‘Invasion’ Changed the World: Drone Warfare Becomes Reality,” March 3, 2023.

※14 Mainichi Shimbun, “We Want to Hear: Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment; Interview with Koji Sugihara, Head of the Network Opposing Arms Exports,” March 16, 2017.

※15 Mainichi Shimbun, “A World in Turmoil: The Trump Shock; U.S. Defense Budget Up 10% ‘Historic’: Overwhelming Other Countries with ‘Strength’—Also Aims to Create Jobs,” March 1, 2017.

※16 Asahi Shimbun, “[Editorial] Export of F-35 Parts: Don’t Turn the Three Principles into Empty Words,” March 2, 2013.

※17 Asahi Shimbun, “(On the Scene of U.S. Nuclear Forces: Part 1) ICBMs Hidden Beneath Snowfields,” May 5, 2021.

※18 Postwar Japan, under its constitution, has adhered to the principle of “exclusively defense-oriented policy,” and thus refers to its forces as Self-Defense Forces rather than as a national army or military. For this reason, the Japanese government refers to what is generally called the arms industry as the “defense industry.” Since it is involved in the purchase and maintenance of military equipment such as fighter jets, warships, and tanks, this article treats it as equivalent to arms industries in other countries.

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

Graphics: Mayu Nakata

軍産複合体って聞いたことない。

報道されないから知らないんだな。

こういうのをもっと報道してほしい!