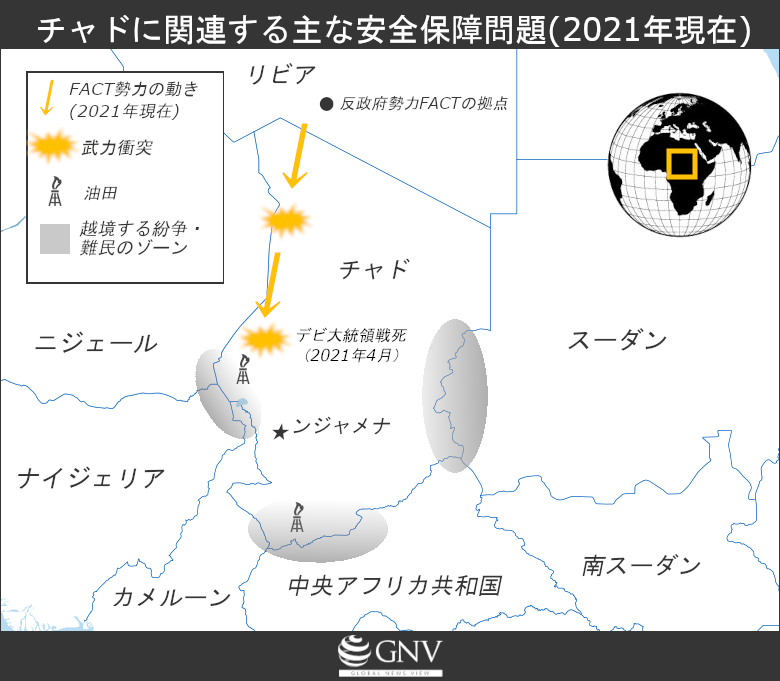

On April 20, 2021, it was reported that Chad’s President Idriss Déby was killed in action while inspecting areas of fighting with rebel forces. This came just as he was widely expected to secure reelection for a sixth term amid increasingly authoritarian rule. After his death, which ended three decades of effective political control, his 37-year-old son, General Mahamat Idriss Déby, assumed the post of interim president in violation of constitutional rules on the order of succession. These developments reflect the reality of a democracy in name only in Chad. Because Chad’s problems are intricately intertwined with conflicts and other security issues in neighboring countries, there are concerns about spillover effects across the region. This article focuses on Chad’s challenges and its relationships with its neighbors.

Former Chadian President Idriss Déby at his 2016 swearing-in after winning a fifth term (Photo: Paul Kagame / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Historical background of Chad

Chad is a landlocked country in Central Africa bordering Libya, Sudan, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, and the Central African Republic, with a population of about 17 million. The territory of present-day Chad and its surroundings have long seen the formation of various ethnic groups and polities. From around the 7th century, there were significant inflows of Arabic-speaking peoples and others from other regions, along with the spread of Islam. As a result, identities in this broader region have been fluid. From around the 9th century, Islamic states such as the Kanem-Bornu Empire, the Bagirmi Kingdom, and the Wadai Kingdom emerged and competed for hegemony. In the 19th century, armed groups from Sudan invaded and seized control, but soon clashed with advancing French forces, who took over. Alongside French influence came Christianity, and today Muslims predominantly live in the north and center, while Christians are more numerous in the south.

Chad gained independence from France in 1960, and the first president was François Tombalbaye, a Christian from the south. Even after independence, France continued to influence governments aligned with French interests under the pretext of providing “support.” Various groups subsequently arose in resistance to authoritarian rule and French involvement. In the mid-1960s, the National Liberation Front of Chad (Frolinat) and the National Front of Chad (FNT) were established, but at the request of the Tombalbaye government, French intervention was permitted to suppress them. Tombalbaye’s dictatorial government was overthrown in a 1975 coup, after which the central government collapsed.

Hissène Habré, who had led a rebel movement, rose to power with support from France and the United States and became president. Beginning in the 1970s, Chad clashed fiercely with Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya. The confrontation began with Libya’s support for Frolinat, but escalated following Libya’s incursions into northern Chad. The Aouzou Strip along the Libyan border, known to contain resources, was occupied by Libya for about 20 years from 1973. French forces intervened to counter Libya’s attacks. The late stages of the Chad-Libya conflict are also known as the “Toyota War,” because Toyota pickup trucks mounted with machine guns were used as key weapons on the battlefield.

The Habré regime, born with support from France and the United States, brutally killed opponents and critics, carried out mass killings under the banner of “ethnic cleansing,” and took the lives of 40,000 people. Amid this, Idriss Déby, who had distinguished himself in Chad’s military, launched a rebellion against Habré in 1989. With the backing of France, Sudan, and Libya—who feared a loss of influence due to Habré’s growing ties with the United States—Déby advanced on the capital, N’Djamena, in 1990.

Political situation

President Déby was from the Zaghawa ethnic group. Under President Habré, he had served as a military adviser and commanded the armed forces. Déby’s seizure of power after overthrowing Habré sparked resistance, including attempted coups by Habré loyalists in 1991 and 1992. After suppressing these forces, Déby assumed the presidency in 1993 and initially promised the nation a multiparty democracy. A new constitution was adopted in 1996, and Chad held its first multiparty presidential election. However, Déby’s three-decade rule was far from genuine multiparty democracy. In the run-up to elections, prominent opposition candidates were arrested or disappeared, prompting opposition boycotts and rendering the multiparty system effectively nonfunctional.

To consolidate his political base, Déby prioritized appointing people with the same ethnic identity to the government and military. From the outset, he filled officer ranks and elite units with fellow Zaghawa, and between 2003 and 2004 frequently reshuffled his cabinet to place family members and other Zaghawa at the center of power, ensconcing them in key positions. In April 2018, parliament approved a new constitution expanding presidential powers. This also abolished the post of prime minister, further entrenching Déby’s authoritarian rule.

Relations with France also continued. After amending the constitution to remove the two-term limit and securing reelection in 2005, Déby visited France a month after the election. French support has included not only direct assistance such as deploying troops to provide rear-guard support in Chad, but also training and technical advice. Beyond military assistance, France has provided development aid, making the two important partners. This relationship has remained unchanged through the transition from former President François Hollande to President Emmanuel Macron.

After President Déby’s death in battle, his son became interim president and dissolved the government and parliament, but he has promised free and democratic elections in 18 months.

Chad’s National Assembly building (Photo: Ken Doerr / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Chad’s economic situation

Déby’s authoritarian politics and foreign relations have also affected Chad’s economy. Placing heavy emphasis on the military, Déby allocated 40 to 50% of the national budget to defense and security. With loans and cooperation from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Chad became an oil producer in 2003, but the results have hardly translated into economic development.

Two major factors explain this. First is corruption and embezzlement by the government, including President Déby. Before providing loans, the World Bank encouraged a legal framework to channel oil revenues into five priority areas: alleviating poverty; education; health and social services; rural development; and infrastructure, including schools. The government enacted a revenue management law and set up an oil revenue oversight committee comprising government and civil society. However, such oversight and regulation do not apply to all oil-related income. The revenue management law covers only direct income such as dividends from oil companies to the government; indirect income such as corporate taxes paid by producing companies and export duties is remitted to the Ministry of Finance and can be used freely by the government. Moreover, the oversight committee’s membership selection was subject to government interference from the start, and even if corruption is detected, the judiciary that should properly address it is not functioning effectively, posing a significant problem.

The second factor involves external actors. Foreign oil companies with capital and technology have taken the lead from extraction to international sales in place of the Chadian government. This means Chad’s share of the benefits is limited, with the remainder siphoned abroad by foreign firms. Much of the contract terms between foreign companies and the Chadian government are not public, but Chad’s oil royalties (Note 1) are set at 12.5%, lower than in other African oil-producing countries. This is partly because the oil produced in Chad is relatively low quality and sells at a discount on international markets. In 2006 and 2016, there were also allegations of tax evasion by American and Malaysian oil companies operating in Chad.

Oil processing facility in Komé (Photo: Ken Doerr / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Beyond industry, currency issues have also affected the economy. Chad uses the CFA franc (Communauté Financière Africaine franc), introduced in 1945 as a common currency for France’s African colonies. A key problem with the CFA franc is its fixed exchange rate. The CFA franc was pegged to the French franc and, after the switch, remains pegged to the euro. As a result, euro appreciation is transmitted directly, disadvantaging CFA-zone countries in export competition. There is also the issue of foreign-exchange reserves: countries using the CFA franc must deposit 50% of their reserves in France’s central bank. By retaining such authority, France ensures that Chad has still not fully escaped the structures of colonialism even today.

Currently, about one-third of Chad’s gross domestic product (GDP) comes from oil exports. Oil production was supposed to be a step toward economic development and alleviating poverty, but poverty remains severe, and Chad is one of the five poorest countries in the world. In the 2020 Human Development Index released by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which evaluates health, education, and income, Chad ranked 187th out of 189 countries, underscoring the scale of its economic challenges.

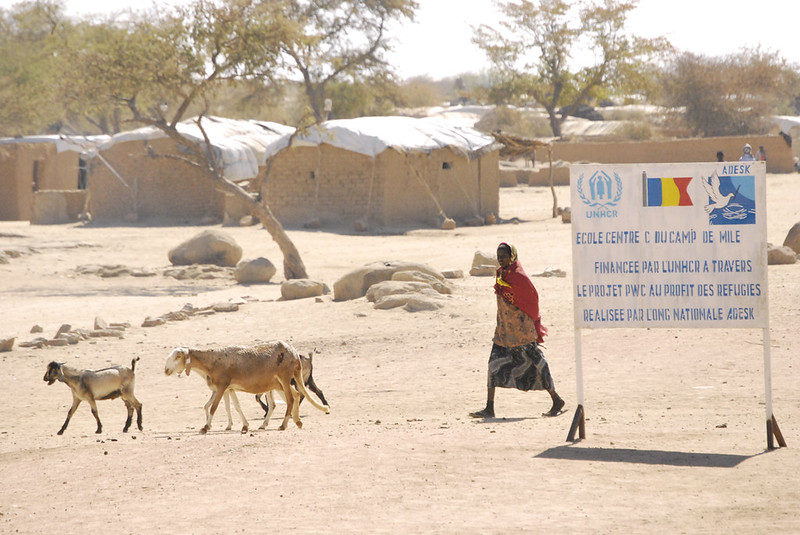

Refugee camp in eastern Chad (Photo: Reclaiming The Future / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Fighting with rebel groups

Déby came to power through an anti-Habré rebellion, but after taking office he himself faced numerous rebel groups. Many rebels are based abroad, which not only shields them from the government’s direct influence but can also provide support or protection from host-country governments. The Movement for Democracy and Justice in Chad (MDJT), led by former defense minister Youssouf Togoïmi and based in the Tibesti region of the Sahara, launched a rebellion in northern Chad in 1998 with the aim of toppling Déby. A peace agreement with the government was signed in January 2002, but anti-ceasefire elements within the MDJT continued fighting, leading to another peace agreement with the government in 2003. After Togoïmi, the movement’s founding leader, died in September 2002, the group fractured.

The largest rebel group under Déby’s rule was the Union of Forces for Democracy and Development (UFDD), led by Mahamat Nouri. Based in Sudan’s Darfur region, it sought Déby’s ouster and mounted major offensives in 2006 and 2008. In the 2008 rebellion, the UFDD even advanced into N’Djamena, the Chadian capital. As the UFDD approached the presidential palace and the Déby regime teetered, French military support helped the government avert collapse. In the wake of the rebellion, Chad severed diplomatic relations with Sudan, accusing it of supporting the rebels.

In 2009, eight rebel groups united to form the Union of Resistance Forces (UFR) and sought to overthrow Déby by invading Chad from Libya in February. In 2016, the UFDD split, giving rise to the Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT). Both groups, based in Libya and calling for Déby’s ouster, share a common trait: many members are Zaghawa, the same group as Déby. One reason Zaghawa joined rebel movements in large numbers was the concentration of power in Déby’s hands. By placing his kin and other Zaghawa in key military and government positions, some of them came to harbor ambitions for the presidency. For such figures, Déby’s constitutional changes to extend his tenure became a catalyst for joining rebel activities. These defections among Déby’s circle also reverberated across the broader Zaghawa community. When the Zaghawa-led UFR penetrated northern Chad, Déby seemed reluctant to counterattack, which may have strengthened the case for French intervention.

A shot-down Chadian attack helicopter (Photo: David Axe / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Relations with neighboring countries

Beyond those mentioned above, Chad has multiple rebel groups, many of which are based in Libya and Sudan. Their connections with the Libyan and Sudanese governments or other Libyan and Sudanese factions cannot be entirely ruled out. At the same time, many senior Chadian officers come from the north and have links with insurgents in Libya and Sudan, making these dynamics too complex to be confined within national borders. To better understand Chad’s situation in context, we explore its ties with neighboring countries.

In 2003, an armed conflict erupted in Sudan’s Darfur region and escalated, leading Chad to accept many refugees. By 2005, the number of refugees from Sudan had reached about 200,000. Following these flows, Sudanese government forces attacked into Chad targeting Sudanese rebels and refugee camps, prompting Chadian military responses. The two governments accused each other of supporting the other’s rebels, further straining relations. Given this background, relations oscillated between hostility and rapprochement, with agreements to halt cross-border conflict and resolve disputes. In 2010, Presidents Déby and Omar al-Bashir met and restored diplomatic relations. Nevertheless, violence in Darfur has continued to increase, and refugees continue to flee to Chad.

Chad’s ties with Libya are also deep. As noted, Chad long antagonized Gaddafi’s Libya. Since the Gaddafi regime fell in 2011, Libya has lacked a stable central government and remains in a state of national instability. Taking advantage of this, Chadian and Sudanese rebels periodically travel to Libya to seek support from Libyan factions opposed to their respective governments. The FACT group that ended Déby’s life was one such group.

Created based on data from The Africa Report and OCHA

Conflict in neighboring Nigeria has also spilled into Chad. Boko Haram, one of the extremist groups based in Nigeria, has invaded Chad and carried out terrorist acts. Similarly, just as Chadian rebels have used neighboring countries as bases, rebels from the Central African Republic have used Chad as a base. In 2013, under the banner of supporting stabilization in the Central African Republic after a coup, Chadian forces were deployed to the country’s east.

In this way, various forces move across borders around Chad and influence one another. These conflicts therefore cannot be understood solely in terms of the nation-state, and the term “civil war” is often inadequate. Because external influence is so pervasive, coordination among countries is frequently necessary. One such effort was the UN peacekeeping mission MINURCAT, which aimed to protect and assist refugees in Chad and the Central African Republic, neighbors of Sudan affected by the Darfur conflict. After four years the mission withdrew, and Chad assumed responsibility.

Perhaps because it has experienced conflicts not only at home but also in neighboring countries, Chad’s national army is regarded as strong and has been deployed abroad. One such deployment has been under the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS). In 2013, after a coup toppled the government of the Central African Republic, the ECCAS mission to intervene was largely carried out by Chad. The mission was handed over to the African Union (AU), but later Chad’s participation was criticized as destabilizing, and it withdrew the following year. In fighting Boko Haram, Chad has also deployed forces to neighboring countries, taking a leading role alongside Nigeria and Niger. Meanwhile, conflict with rebels and turmoil caused by coups in Mali have spread to neighboring Niger and Burkina Faso, raising the threat across the Sahel (Note 2). In early 2021, Chad pledged to send 1,200 soldiers to the tri-border area of these three countries.

Chadian soldiers training in Niger (Photo: US Africa Command / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

France and the United States’ enduring focus on the region

Chad’s powerful military is also useful to France and the United States. Since the late 19th century and even after independence, France has consistently remained involved in Chad in various forms. It provided extensive military support to the fight against rebels under the Habré regime and the Déby regime, and backed Chadian forces when Libya attacked northern Chad.

Chad has likewise supported French military operations. In 2013, it assisted France in pushing back rebels from northern Mali, and in 2014 it participated when France launched operations to suppress extremist groups in the Sahel. To coordinate the fight against extremist groups, five French-speaking West Sahel countries—Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad—established the G5 Sahel in 2014, and France conducts military operations jointly with the G5 Sahel Joint Force alongside them.

With an air base near N’Djamena and about 5,000 personnel operating in the Sahel, Chad is a key strategic hub for France in Africa. It is also crucial for monitoring the unstable situation in Libya. Economically, Chad’s location offers easy access to natural resources and markets in neighboring countries. The CFA franc is another economic benefit for France. By maintaining close ties with Chad and exerting influence, France aims to secure military and economic interests not only in Chad but across the region.

French and Chadian forces raise their flags ahead of operations against extremist groups (Photo: U.S. Army Southern European Task Forc / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

For the United States, too, Chad is an important partner for countering extremist groups. Together with France, the United States supported Déby’s regime at key moments, including when Habré came to power, when Libya invaded Chad, and during the military buildup in the Sahel. As the United States considered Libya a state sponsor of terrorism, Chad took on added importance. There were also expectations around oil. As the world’s second-largest energy consumer after China, the United States has sought to advance oil development in Africa as a new supply source, and major U.S. oil companies played central roles in Chad’s oil development.

Conclusion

Immediately after the announcement of Déby’s death in combat with rebels, French President Macron visited Chad to pay his respects. Beyond attending the funeral, his statement supporting the regime of Déby’s son—who assumed the interim presidency in defiance of democratic norms—suggests a continued intent to prioritize the status quo and French influence over democracy.

There have been criticisms from within the military over the unconstitutional assumption of the presidency. A 30-year-long regime has ended in Chad, but with elections promised in 18 months, is this truly a “transition period”? After the elections, will Chad move toward democracy, or proceed with business as usual? The future of Chad—and of the broader Sahel—bears close watching.

Note 1: A mining royalty paid to the resource-holding country in exchange for the right to extract minerals in a specific area and sell them as commodities abroad.

Note 2: A semi-arid belt along the southern edge of the Sahara, stretching across Africa from Senegal in the west to Eritrea in the east.

Writer: Rioka Tateishi

Graphics: Takumi Kuriyama

このサイトに初めてアクセスしました。日本ではどのマスコミも全然、報道しないネウースを

詳しく報道していただき、大変っ勉強になります。

有難うございました。