At GNV, we have analyzed disparities in international news coverage from various angles. In the course of advancing our analysis of the news, we have identified the phenomenon that some regions receive extensive coverage while others are rarely reported on. Factors that create differences in volume include the population and economic scale of a country or region, but arguably even more important is its relationship with Japan.

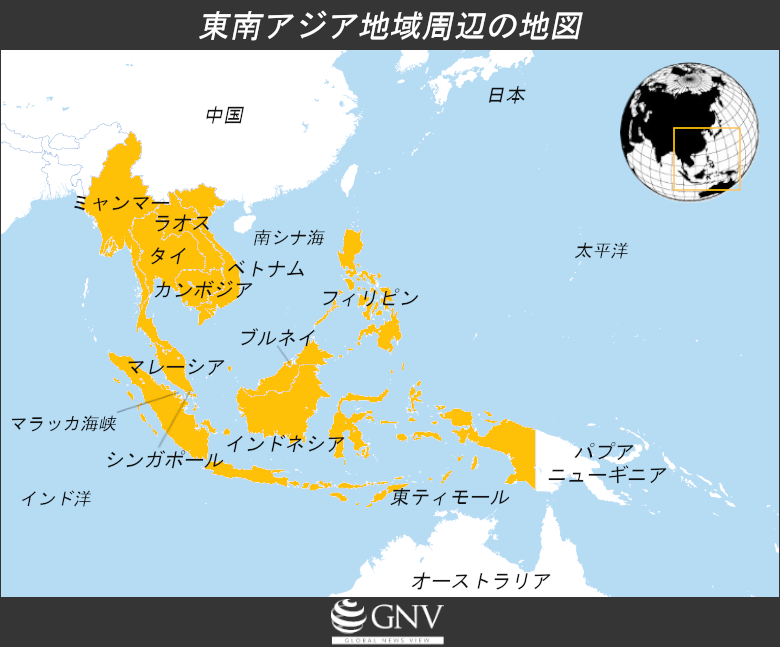

This time, we focus on Southeast Asia, a region geographically close to Japan, and analyze its amount of coverage. Southeast Asia accounts for about 10% of the world’s population of more than 7.8 billion and has achieved remarkable economic growth in recent years. It also has deep ties with Japan in many respects, starting with trade. Do Japanese media reflect the region’s scale and its relationship with Japan in the amount of coverage?

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (Photo: hams Nocete / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

目次

Overview of Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia consists of 11 countries: Indonesia, Cambodia, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste, the Philippines, Brunei, Vietnam, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Laos. The region’s total population is about 680 million; among them, Indonesia has the largest population at about 280 million, fourth in the world after China, India, and the United States. Southeast Asia is home to diverse ethnic identities, languages, and religions, with multi-ethnic states formed across national borders. For example, in Singapore, the population is composed of roughly 76% ethnic Chinese, 15% Malay, and 7.5% Indian, reflecting a variety of identities and ethnic roots. In terms of language, many indigenous languages exist. Despite being multi-ethnic states, many countries add the language of a former colonial ruler to major local languages and designate multiple official languages. With the movement of people and goods, various religions have also spread. Buddhism predominates in mainland countries such as Thailand and Myanmar; Islam in Indonesia and Brunei; and Christianity in the Philippines. Minorities practicing other religions also exist in each country.

Economically, the combined GDP of the countries exceeds 3 trillion USD, accounting for about 3.5% of the world’s GDP. By country, GDP is largest in Indonesia (16th globally), followed by Thailand (26th) and the Philippines (32nd). Comparing per capita GDP, Singapore’s is about 60,000 USD (8th in the world), whereas Cambodia, Myanmar, and Timor-Leste are around 1,500 USD, creating a 40-fold gap. In addition, Timor-Leste had a high multidimensional poverty rate of 45.8% as of 2019. This goes beyond purely monetary indicators and represents the proportion of people living in poverty considering daily dimensions such as health, education, and living standards. Thus, even within Southeast Asia, economic disparities are pronounced.

In recent years, Southeast Asian countries have experienced remarkable economic growth. Since its independence in 1965, Singapore’s policies, such as attracting foreign companies and promoting tourism, have succeeded in driving growth. Its growth is historic, and it is now known as an Asian hub for logistics. Vietnam, meanwhile, recorded stable growth averaging 6.3% from 2011 to 2019, with growth rates exceeding 7% in 2018 and 2019.

Economic and political coordination has also progressed to some extent, exemplified by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). ASEAN was established in 1967 by five countries—Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, and Malaysia—to build friendly relations. Brunei joined in 1984, Vietnam in 1995, Laos and Myanmar in 1997, and Cambodia in 1999; today, 10 countries—excluding Timor-Leste—are members. Various meetings and conferences are held annually in ASEAN countries, starting with the ASEAN Summit, the highest decision-making body. Centered on such meetings, ASEAN makes recommendations to member states and works to build relationships within a broader framework that includes non-member countries, strengthening coordination and economic cooperation. In 1993, the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) agreement was concluded, enabling the removal of tariff barriers on all products produced within the region. Although the share of intra-regional trade has been on a declining trend at around 20% for both exports and imports, extra-regional trade with partners such as China and the United States has increased accordingly.

Hanoi, Vietnam (Photo: Funcky Chickens / Flickr [CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Looking at political systems, many Southeast Asian countries have not established robust democracies. The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) classifies countries into four types, from highest to lowest level of democracy: “full democracies,” “flawed democracies,” “hybrid regimes,” and “authoritarian regimes.” According to the EIU’s Democracy Index 2020, Cambodia, Vietnam, Myanmar, and Laos have the lowest level—authoritarian regimes. Other countries, while under democratic systems, are classified as flawed democracies, leading to the assessment that none in Southeast Asia fully realizes a democratic system. The lack of consolidated democracy is also suggested by coups d’état. In recent years, there was a military coup in Thailand in 2014 and in Myanmar in 2021, showing that the militaries in those countries still retain power.

Security issues in Southeast Asian countries extend beyond coups; the region also faces numerous armed conflicts. While the Rohingya refugees resulting from conflict in western Myanmar have drawn attention, armed conflicts have also frequently occurred in northern and eastern Myanmar. In recent years, conflicts have also occurred in southern Thailand, on the Philippine island of Mindanao, and in Indonesia’s Aceh and West Papua. These long-running conflicts have contributed to persistent political instability across the region.

Relations between Southeast Asia and Japan

Next, we look at the relationship between Japan and Southeast Asia. During World War II, Japan turned to Southeast Asia with the aim of securing resources to continue the Second Sino-Japanese War. Alongside the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Japan landed on the Malay Peninsula and then successively occupied Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Burma (now Myanmar), the Philippines, and Malaysia. Until its defeat in 1945, Japan imposed colonial rule in Southeast Asia, sacrificing the lives and livelihoods of millions. Despite this history, what is the current state of relations between Japan and Southeast Asia? We examine four aspects.

The first is trade. The total value of trade between Japan and ASEAN countries exceeded 23 trillion yen (2019), accounting for 15% of Japan’s overall trade. Among these, Thailand and Vietnam rank among Japan’s top 10 trading partners. Japan’s main exports to ASEAN countries are steel, semiconductors and electronic products, and auto parts, while ASEAN’s main exports to Japan include liquefied natural gas and clothing and accessories. About 69% of the natural rubber imported into Japan comes from Indonesia, and about 20% of shrimp imports come from Vietnam. This indicates that Japan and Southeast Asia are important trading partners for each other.

A mountain of cargo bound for Singapore (Photo: Storm Crypt / Flickr [CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The second is industry. Since the late 1980s, Japanese companies have actively invested directly in Asia, fostering the development of cross-border production networks. Southeast Asian countries, in particular, have been positioned as important manufacturing bases with relatively low labor costs, and manufacturing has developed strongly. Japanese companies’ expansion into Southeast Asia has enhanced their competitiveness, accelerating their advance into the region. For example, 1,489 Japanese companies (2019) operate in Indonesia, 60% of which are in manufacturing—especially transport equipment parts and electrical/electronic products. Similarly, 1,385 Japanese companies (2018) operate in Malaysia, with manufacturing related to electrical and electronic products making up the largest share—over 30% of manufacturing firms. Supporting industries such as electronic components are also thriving, and Malaysia has developed into a cluster for electronics and electrical industries. In recent years, as Japanese firms have established more local subsidiaries in Southeast Asia, items previously imported from Japan are increasingly produced locally. At the same time, more companies are expanding to develop markets by producing closer to consumers.

The third is security. Japan places particular importance on maritime routes in Southeast Asia. In maritime trade between Japan and Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia, merchant ships pass through the Strait of Malacca, located between Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula, and the South China Sea. According to 2007 data, Japan imports 80% of its energy resources and 60% of its food via the Strait of Malacca. Japan is not alone in prioritizing maritime routes through Southeast Asia. In 2020 global maritime trade, one-fifth of traded goods and one-third of oil were transported through the Strait of Malacca.

One concern for Japan is China’s advance into the South China Sea. There are tensions between Southeast Asian countries claiming sovereignty in the South China Sea and China; if these tensions escalate, there are concerns that Japan’s use of maritime routes could be hindered. In addition, piracy in waters around Southeast Asia has occurred along routes used by Japanese merchant ships. Although the number of incidents has declined in recent years, incidents still occur. Addressing piracy is therefore necessary to ensure safe maritime traffic for Japan as well.

A warship transiting the Strait of Malacca (Photo: U.S. Pacific Fleet / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Armed conflicts in Southeast Asia also relate to Japan. For example, Indonesia’s Aceh conflict lasted over 30 years and ended in 2005. Centered on a dispute between the Indonesian government and anti-government forces over resource-rich Aceh, the main export destination for Aceh’s natural gas at the time was Japan. As noted earlier, the Philippine island of Mindanao has seen conflict for half a century. Japan imports most of its bananas from the Philippines, and 84% of bananas produced in the Philippines come from Mindanao. In this way, armed conflicts in Southeast Asia are not someone else’s problem for Japan.

The fourth aspect is people-to-people exchange. With rapid economic growth, the middle class has expanded in Southeast Asia, and low-cost carriers have entered the market. Interest in Japanese society and culture has also grown, and Japan has become a popular tourist destination. As a result, the number of visitors to Japan has increased, reaching about 3.8 million in 2019 from six Southeast Asian countries (Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia), or 12% of all inbound visitors. Meanwhile, the number of Japanese departures to ASEAN countries (2018) was about 5.2 million, 27.6% of all Japanese departures. Although travel has been restricted as of September 2021 due to the spread of COVID-19, the number of visitors to Southeast Asia from Japan increased year by year from 2011 to 2019. Being relatively close to Japan, rich in tourism resources, and more affordable, many Japanese visit for tourism.

Flows of people between Japan and Southeast Asia are not limited to tourism. The number of Japanese residents in Southeast Asia is about 200,000, accounting for 16% (2020) of all Japanese living overseas. Conversely, the number of Southeast Asian residents in Japan is about 900,000, or 32% (2020) of all foreign residents. By nationality, Vietnamese make up the largest group of foreign workers in Japan at about 440,000, or 25% of all foreign workers, followed by about 420,000 Chinese (24%) and about 190,000 Filipinos (11%). By residence status, the largest group is those with status based on family ties (Note 1) at about 550,000 (32%), followed by about 400,000 technical interns (23%) and 370,000 engaged in activities outside their status, including students (21%). As a concrete example, Filipinos account for about 70% of crew members on Japanese international merchant vessels. From the perspective of people-to-people exchange as well, the relationship between Japan and Southeast Asia is very deep.

Bananas from the Philippines (Photo: Shubert Ciencia / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Analysis of 2019 coverage volume

We have seen that Southeast Asia is large in demographic and economic terms and has very deep ties with Japan in many respects. From this, it would be reasonable to expect this region to receive significant attention in Japanese media. But is that actually the case?

To analyze Japanese coverage of Southeast Asia, we examined Yomiuri Shimbun’s reporting on 11 Southeast Asian countries in 2019 (Note 2). Of a total of 12,121 international news articles, 488 concerned the 11 Southeast Asian countries (Note 3), a mere 4.0% of international coverage—extremely low. Moreover, many of these articles dealt with relations between Southeast Asian countries and other countries or regions—such as Japan–Thailand relations or U.S.–China relations in Southeast Asia. If we limit the scope to reporting solely on Southeast Asian countries, the volume is smaller still: only 184 articles (37.7%) focused exclusively on Southeast Asian countries. Among articles involving countries outside the region, Japan accounted for the overwhelming share, but China-related articles were also relatively frequent. In many cases, Southeast Asia was merely the stage for events elsewhere rather than the subject of the reporting. For example, when the U.S.–North Korea summit was held in Vietnam in 2019, most of the reporting was not about Vietnam but about the United States and North Korea.

However, the limited volume of coverage is not unique to 2019. Aggregating the number of articles on the 11 Southeast Asian countries in the Yomiuri Shimbun from 2015 to 2017 (Note 4), the share of international coverage devoted to them was about 4.5% in 2015, 4.7% in 2016, and 3.4% in 2017. Thus, even across these three years, Southeast Asia consistently accounted for around 4% of international reporting, making it easy to infer that the volume has been low over the longer term. Considering Southeast Asia’s population, economic scale, and strong ties with Japan as mentioned earlier, can we really say the region’s “news value” is adequately reflected?

What is being reported?

So what exactly was reported within the 488 Southeast Asia–related articles in 2019? By country, Thailand had the most coverage with 82.9 articles (17.0%), followed by Indonesia with 49.9 (10.2%), Vietnam with 44.2 (9.1%), and the Philippines with 43.9 (9.0%). By contrast, Laos and Brunei had 1.5 articles each, and Timor-Leste had 0, indicating disparities within the region.

Next, what kinds of events were covered? Topics involving ASEAN were frequent, totaling 38.3 articles, notably about the ASEAN Summit and meetings related to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which includes ASEAN countries and Japan. Country by country, general elections in Thailand and Indonesia in 2019 contributed to increased coverage: there were 31 articles on Thailand’s election and 11 on Indonesia’s. There were also seven articles each on Myanmar’s government and armed groups, and on Rohingya refugees. Among articles focused on internal developments within Southeast Asian countries, politics featured prominently.

Meanwhile, how were relations between Southeast Asian countries and others covered? Articles related to Japanese companies and technology were relatively numerous at 26 out of 488, but most were about Japanese firms expanding into Southeast Asia or establishing production bases. There were 25 articles about Southeast Asians planning to work abroad, often featuring trainees aiming to work in Japan—typically explicitly mentioning Japan. As for long-standing issues, there were also 16 articles about China and the South China Sea, as noted earlier.

What went unreported?

We have analyzed the breakdown of coverage volume. Conversely, among relatively significant events in 2019, what went unreported or received relatively little coverage? One important development was the establishment of a provisional autonomous government in the Philippines in connection with the Mindanao conflict—an initial step toward peace after half a century of conflict. There were only three articles on this (Note 5). Also in 2019, the first trial was held for former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak, who had been charged with corruption. This case, involving the diversion and embezzlement of funds between 2009 and 2014, was described as one of the world’s largest corruption scandals. It was covered in just one article, and only in brief, noting that the former prime minister pleaded not guilty (Note 6).

There were also major disasters that were underreported. From July to October 2019, large-scale air pollution occurred over wide areas of Southeast Asia. This stemmed from slash-and-burn agriculture across Indonesia, which led to massive forest fires. Not only did they burn 860,000 hectares, but smoke containing harmful substances spread from the fire sites, crossing borders and blanketing neighboring countries in polluted air. Despite impacts on the health of both people and wildlife, there was only one article on this (Note 7).

Forest fires on Kalimantan, Indonesia (Photo: Prachatai / Flickr [CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In addition, in Singapore and Vietnam, there were concerns about laws introduced to address fake news. On this, there was one article about the first actual application of the law in Singapore (Note 8). Also, when Brunei implemented a law making same-sex relations punishable by death—heavily criticized internationally—there was no coverage. Thus, even relatively major events were barely reported in the Yomiuri Shimbun.

After the analysis

Southeast Asia is a region that accounts for about 10% of the world’s population and 3.5% of the world economy in terms of GDP. There are also various political, economic, and security developments within the region. Given its deep relationship with Japan, one would expect a certain level of coverage. In reality, however, the volume of coverage is relatively low. What lies behind the gap between this potential “news value” and the actual amount of reporting? Two factors come to mind. The first is that Japanese media show greater interest in high-income countries than in low-income countries. Although Southeast Asia is growing, as a region it cannot yet be described as high-income like Europe and the United States, and it may not be at the center of attention. The second is a tendency for Japanese media to focus on direct threats to Japan. The Japanese government and news organizations appear to focus on places perceived to pose direct security threats, such as China and the Korean Peninsula. As noted above, Southeast Asia is related to Japan in security terms, but perhaps because it is perceived as indirect, it is a secondary priority for news organizations.

Southeast Asia is expected to continue growing, and its relationship with Japan will deepen accordingly. When will Japanese media recognize its importance?

Note 1: “Status of residence based on personal status” includes permanent residents; spouses, etc. of Japanese nationals; spouses, etc. of permanent residents; and long-term residents.

Note 2: We selected 2019, before the spread of COVID-19, because the pandemic was expected to strongly affect international news trends.

Note 3: To search for articles, we used Yomiuri Shimbun’s online database “Yomidas Rekishikan.” We targeted international news only over one year from January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019, searched by the names of the 11 Southeast Asian countries, and extracted only the relevant articles. To count each article accurately, when a single article covered two countries, each was counted as 0.5 article; when it covered three countries, each as 0.333 article; for four countries, each as 0.25 article; and for five countries, each as 0.2 article. For items involving more countries, such as ASEAN-related articles, we counted them as Southeast Asia as a whole or as global.

Note 4: Based on data used in compiling GNV’s Monthly Reports, we aggregated the number of articles on the 11 Southeast Asian countries.

Note 5: In addition to “Islamic autonomy in the Philippines: Territory decided—Mindanao: 5 provinces, 1 city, 63 villages,” Tokyo morning edition, 2021/2/16, there were two other articles.

Note 6: “Former Prime Minister Najib pleads not guilty,” Tokyo morning edition, 2021/4/4.

Note 7: “Indonesia: Severe haze—Forest fires continue—Asthma and other cases surge,” Tokyo morning edition, 2021/10/8.

Note 8: “Singapore: Fake news measures applied for the first time—Government orders correction of FB post,” Tokyo morning edition, 2021/11/28.

Writer: Mayuko Hanafusa

Graphics: Mayuko Hanafusa

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks