What comes to mind when you hear “corruption”? Misconduct by senior government officials and civil servants, diversion of funds, embezzlement, and so on. But corruption does not always stay within national borders. Through shell companies and tax havens, money crosses borders, involving far more people, companies, and countries than one might imagine, with enormous sums circulating around the globe. In the midst of this, wrongdoing dubbed “the world’s worst corruption” occurred in Malaysia between 2009 and 2014. Over the past few years, the corruption in Malaysia at the center of allegations became a major scandal for the government, particularly former Prime Minister Najib Razak. Najib was indicted in July 2018, and in April 2019 the first hearing was held at the High Court.

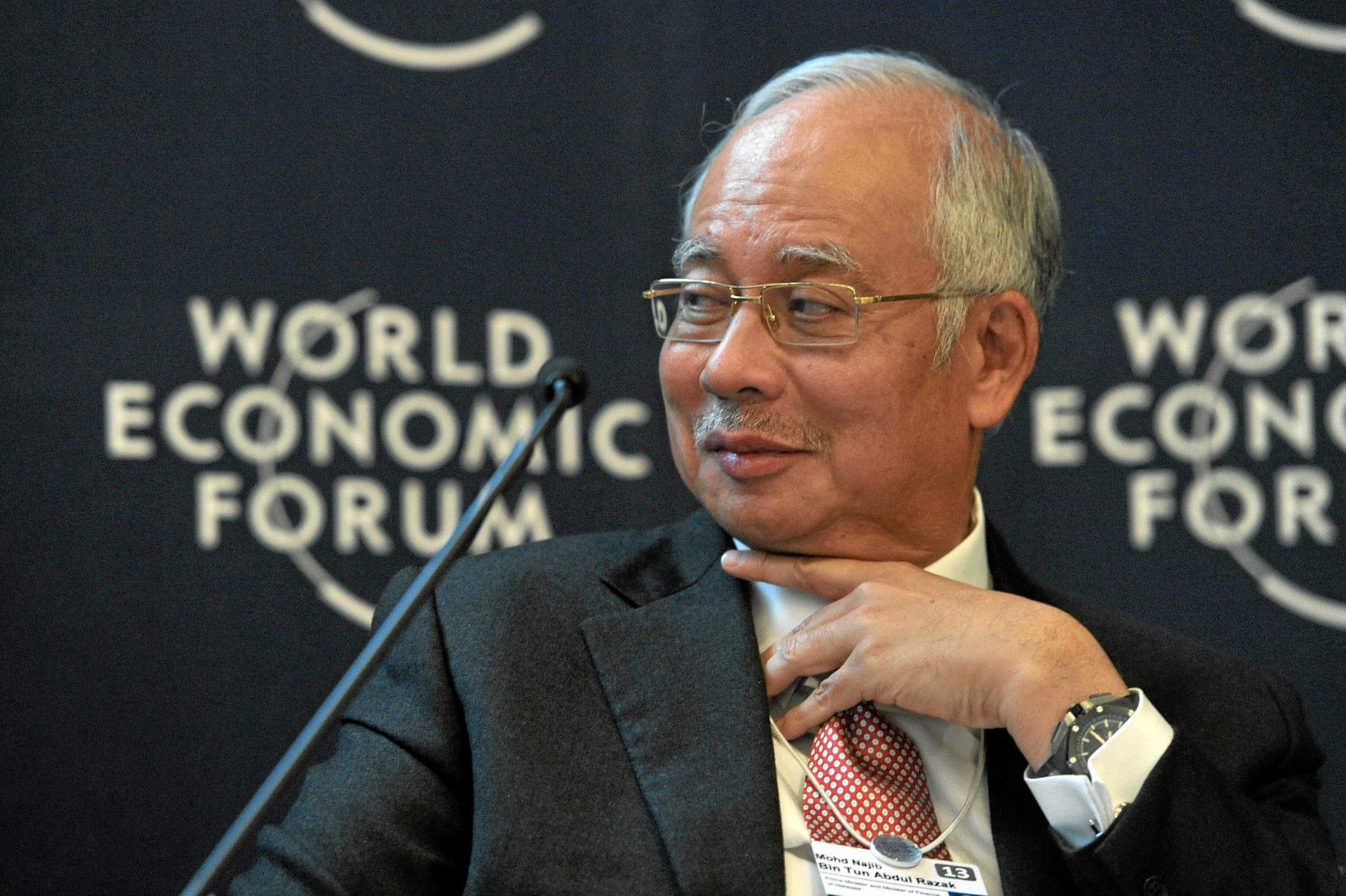

Former Prime Minister Najib Razak (World Economic Forum/Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

This case ended up entangling not only Malaysia’s former prime minister, his family, and close associates, but also U.S. financial giant Goldman Sachs, banks in Germany and Switzerland, and even Hollywood movie stars. It is said that misappropriated funds were used to finance the production of the well-known Hollywood film The Wolf of Wall Street—ironically, a movie that depicts corruption and illicit moneymaking. Why and how has the corruption in Malaysia affected the world? Let’s dig into the reality.

“The world’s worst corruption”

First, let’s look at the big picture. The story begins in 2009. Upon becoming prime minister, Najib Razak established the state investment company 1MDB (1Malaysia Development Berhad). 1MDB’s stated aim was to revitalize the capital Kuala Lumpur as the hub of Southeast Asia’s economy. However, while claiming to promote and diversify domestic industries, funds were in fact diverted and embezzled. Shell companies were set up in Malaysia, Singapore, Seychelles, the British Virgin Islands, and elsewhere, and lax, secrecy-friendly tax havens were used. To obscure where the money came from and where it went, funds were routed through these tax havens and transferred far more times than necessary. The money was laundered by moving it through multiple accounts to make illicit funds look legitimate.

The amount misappropriated from 1MDB—the source of funds for the corruption—reached $4.5 billion between 2009 and 2014 and was spent by various actors on luxury goods, high-end condominiums, and famous paintings. Najib is alleged to have embezzled nearly $700 million of that. He faces 42 criminal trials related to this scandal. Others indicted include Najib’s wife, Rosmah Mansor, financier Jho Low, and former Goldman Sachs employees; banks in Switzerland, Singapore, the United States, and elsewhere have also come under investigation. A very large number of actors are involved: numerous countries (many of them tax havens), shell companies, banks, financial firms, and movie production companies.

1MDB signing a real estate-related contract (Bernardyong [CC BY-SA 4.0])

How the corruption unfolded: four phases

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, the roughly five years (2009–2014) during which diversion and embezzlement took place can be divided into four phases: the “Good Star phase,” the “Aabar-BVI phase,” the “Tanore phase,” and the “Options Buyback phase.” Let’s look at them in order.

① Good Star phase: 2009–2011

1MDB was established in July 2009, and in September, shortly thereafter, it set up a joint venture with the Saudi energy firm PetroSaudi International (PSI). The stated aim was to leverage PetroSaudi’s patents. However, $700 million of 1MDB’s $1 billion capital contribution went to a Seychelles company called Good Star. This company was owned by Malaysian financier Jho Low, who was involved in setting up 1MDB and had ties to Najib and people around him. Good Star was a vehicle for misappropriation from the outset, and further transfers from 1MDB to Good Star followed. The diverted funds were sent to a bank account in the name of Eric Tan (later identified as Jho Low). Money was also sent to an account under the name “Malaysian Official 1 (MO1),” later revealed to be Najib. Outflows from Good Star continued, moving through Swiss banks and various shell companies, and were used for purchases of luxury goods and a private jet, investments in real estate, and the acquisition of shares in a music company. Jho Low’s father, Larry Low, is also said to have been involved.

② Aabar-BVI phase: 2012

In 2012, 1MDB raised $3.5 billion and issued bonds to acquire domestic energy assets, but about $1.4 billion of that was misappropriated. Goldman Sachs underwrote these bonds, charging fees far above market rates (a total of $600 million together with the Tanore phase below), and Goldman employees are alleged to have been involved in the embezzlement.

During this period, a company called Aabar, based in Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates, operated behind the scenes under an agreement with 1MDB. Aabar is a subsidiary of Abu Dhabi’s oil investment company IPIC. Proceeds from this agreement soon flowed to a trust company in the British Virgin Islands called Aabar-BVI. Those funds then moved through shell companies and arrived at companies owned by Eric Tan (Jho Low). Here, two figures emerged who were senior executives at the Abu Dhabi companies at the time: Khadem Al-Qubaisi and Mohamed Al-Husseiny (these two individuals). From Jho Low’s companies, transfers were made to companies owned by each of these men, and the funds were used, for example, to purchase luxury condominiums in Beverly Hills. Money also flowed to MO1 (Najib) and to Jasmine Loo, a former 1MDB employee, and was used to purchase U.S. properties.

Elsewhere, more than $200 million went from Aabar-BVI to Red Granite Pictures, a film company owned by Najib’s stepson Riza Aziz, and these funds were used to produce three Hollywood films, including The Wolf of Wall Street. Riza also used funds—routed through shell companies—to buy a luxury condominium and to spend in casinos and on movie posters. Funds also flowed from Good Star to Jho Low and Larry Low, and, for example, Jho Low’s mother is said to have been given jewelry. In 2018, four people, including former Goldman Sachs employees, were indicted on charges of bribing officials in Malaysia and Abu Dhabi in connection with the bond offerings.

Goldman Sachs Tower, New Jersey, USA (Wally Gobetz/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

③ Tanore phase: 2013

In 2013, to launch a new project, 1MDB again had Goldman Sachs underwrite a $3 billion bond issue, but about $1 billion was sent to a Singapore account in the name of a company called Tanore. Tanore was also owned by Eric Tan (Jho Low). In March 2013, there were suspicions that $680 million flowed from Tanore into Najib’s personal account, but Najib claimed it was a personal donation from the Saudi royal family and said that $620 million of it was returned. However, the $620 million was sent back to Tanore and, through a shell company, used to purchase a luxury necklace for his wife Rosmah. Large sums also went from Tanore to Jho Low, who bought luxury goods and paintings. Some of these high-end items were gifted to celebrities such as model Miranda Kerr and actor Leonardo DiCaprio, drawing Hollywood into the scandal. In addition to Larry Low, Jho Low’s brother Low Teck Szen was also implicated this time.

④ Options Buyback phase: 2014

In 2014, 1MDB took out a $1 billion loan from Deutsche Bank to secure returns for Aabar. However, $850 million of that was sent to companies called Aabar-Seyshelles and Aabar-BVI (both with Mohamed Al-Husseiny as an executive). The loan then returned, via shell companies, to MO1 (Najib), his wife Rosmah, and Jasmine Loo. Likewise, Jho Low obtained laundered funds through numerous shell companies and once again gifted jewelry and other items to Miranda Kerr. When the scandal came to light, both Miranda Kerr and Leonardo DiCaprio returned the gifts.

The situation in Malaysia: where the trial stands

In response to this chain of events, public resentment toward former Prime Minister Najib mounted in Malaysia, even leading to demonstrations. Public opinion was likely reflected in the May 2018 election in which Mahathir bin Mohamad was elected prime minister in place of Najib. At the time of writing, Najib and his wife are barred from leaving the country, but he maintains his innocence in court. In fact, the trial has been postponed multiple times, and some say Najib is trying to delay the verdict as much as possible. His aim may be to return to politics and use power to quash the charges and have prosecutors drop the case. Perhaps in an effort to stage a comeback or to boost his public approval, he even recorded a music video with his family and posted it on YouTube. In similar corruption cases in Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia, high-ranking officials are often not prosecuted while in office, and matters are glossed over and immunity is frequently granted. Conversely, this trial has attracted attention from neighboring countries in terms of expectations for the judiciary and due process. The current prime minister, Mahathir, is also determined to thoroughly pursue Najib’s crimes.

Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (Uwe Aranas/Wikimedia Commons[CC BY-SA 3.0 ])

In 2015, the Wall Street Journal, citing a leak from a whistleblower, reported that nearly $700 million had flowed into Najib’s personal account. After demonstrations broke out in response, Najib reshuffled his cabinet to shut out opposition, and even ordered the arrest of journalists critical of the government and the suspension of business newspapers that reported on the allegations. Yet when the media report facts and inform the public, public opinion can influence election outcomes and bolster court proceedings like this one. This reminds us once again of the importance of the media as a foothold for exposing government wrongdoing and corruption and correcting course.

Global corruption

As a result, 1MDB ended up shouldering about $13 billion in debt. The Malaysian scandal happened to attract great attention, but it is only one example showing the globalization of corruption. There are countless cases of cross-border corruption. Corruption and embezzlement are not merely the problems of politicians in a given country and their associates; by exploiting lax regulation in the global financial system and using tax havens to create smokescreens, major financial firms, banks, and their employees make these flows possible. The amounts diverted and the number of people involved swell because the funds move globally. In light of this case, the resolve to combat corruption is being tested not only in Malaysia but also in each country where indictments have been filed. At the same time, this incident should prompt us to rethink how the global financial system that links the entire world ought to function.

*Note 1: The diagrams representing the four phases in this article were created based on “$tolen” 1MDB funds: The DOJ lawsuit revisited (Lee Long Hui). These diagrams are simplified; in reality the scheme is more complex and involves more actors.

Writer: Madoka Konishi

Graphics: Kamil Hamidov

We also post on social media!

Follow us here ↓

文字通り、「汚い」事件ですね。

この汚職がうやむやにされぬよう、司法と市民が汚職に関わった人々をしっかりと裁くことを期待します。

文中にもありましたがここでメディアの監視による抑止力が重要なポイントだと感じました。

最近ではいろんな国で知る権利や通信や報道、表現の自由を脅かしたりする法案が見え隠れしつつあります。(つい最近だとシンガポールがやばそう)

このような権力の濫用を裁き抑止する正義が、世界共通の財産として根付くのはいつだろうと夢見るばかりです……

汚職には想像以上に沢山のアクターが関与しているのだなと思いました。これほど越境的にお金が動いていると一国の努力だけでは改善ができないので、根本的解決は難しいように思います。汚職に関わっている他国企業を起訴したりってできるのでしょうか?

これほど多くのアクターが複雑に関与している事件が実際に存在すること自体に驚きました。『ウルフ・オブ・ウォールストリート』のこともとても皮肉だなと思いました。タックスヘイブンやペーパーカンパニーのことについてもっと知りたいです。

汚職はいずれ発覚するのに、イメージ第一なはずの政治家たちばっかりが汚職に関わる理由が理解できないです。

これほどの汚職事件が一定期間ばれなかったことに驚きでした。

タックスヘイブンなどを利用して世界規模でお金が動き、世界規模で汚職が行われていて驚きました。世界規模でこうした汚職が行われないように一国だけでなく世界的なシステム構築の必要性を感じました。

様々なアクターが上手く機能して、これほど複雑に絡まった汚職が成立していたことがすごいなと思った。

「グローバル化」がうたわれる現代社会ですが、弊害としてこのような世界規模の金融の流通による汚職も挙げられるなと気づかされた。

世界には貧困や環境問題、教育問題などまだまだ解決されなければならない問題が山積みなのに、その問題を目の前にしてこのような事件が起こっていると思うととても悲しい気持ちになる。