In September 2019, demonstrations broke out in West Papua, Indonesia, in response to racist remarks. In the highland town of Wamena, residents participating in the protests were suppressed by police units, and Nearly 40 deaths were reported. However, this was not the first conflict between West Papuans and the Indonesian government; such clashes have been repeated for decades. Behind these frictions lie various factors, including human rights abuses against West Papuans and the issue of independence. This article explores the situation unfolding in West Papua.

A protest held in Australia for West Papuan independence (Photo: Nichollas Harrison/Wikimedia [C.C. BY-SA 3.0])

目次

Background on West Papua

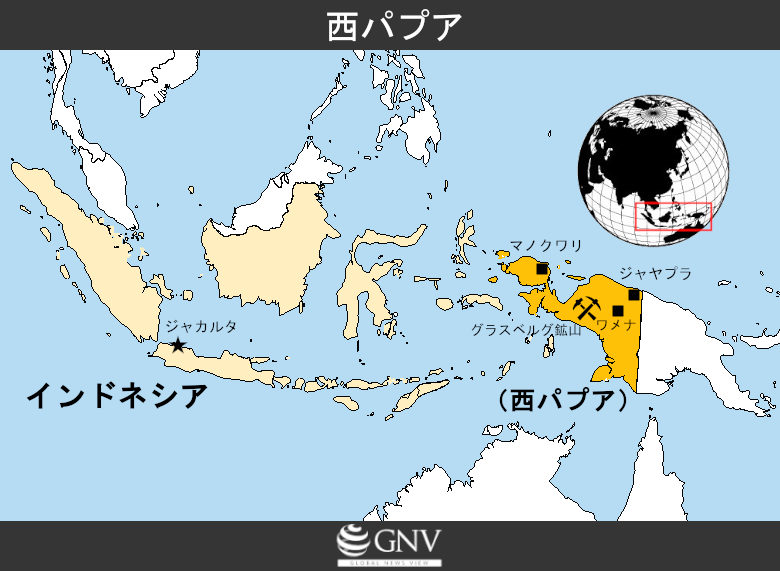

West Papua (Note 1) lies on Indonesia’s eastern side, bordering Papua New Guinea. Around 250 Indigenous Melanesian (Note 2) groups live there; today about half the population is Indigenous Papuan, and the other half consists of migrants from other Indonesian islands.

Like other Indonesian territories, West Papua was a Dutch colony from the 1800s, and from 1942 to 1945 it was occupied by Japan. After the end of World War II, Indonesia gained independence from the Netherlands, but West Papua—rich in mineral resources—remained under Dutch control. However, calls for independence among West Papuans continued to grow, and in the 1950s the Netherlands, together with the United Nations, began preparatory support for West Papua’s independence. On December 1, 1961, a declaration of independence was made and the flag was unveiled for the first time.

Meanwhile, the Indonesian government argued that the colonial borders, including West Papua, should become “Indonesia” as they stood, and it began planning to develop the region’s abundant resources. Several foreign companies also set their sights on West Papua. For example, the American mining company Freeport entered into negotiations over mining rights in West Papua with Major General Haji Mohammad Suharto, who would later become Indonesia’s president. These talks were conducted in secret and were not disclosed to either the Netherlands or West Papua.

By 1962, Indonesia attempted to invade West Papua by force, but failed because the Dutch military had intercepted Indonesian strategies. Amid this, the United States proposed concluding the New York Agreement to halt the struggle between Indonesia and the Netherlands. Under the terms of the agreement, West Papua would first be transferred from the Netherlands to the United Nations, and then handed over to Indonesia in 1963. The Netherlands, under pressure from the United States and others and seeking to end the prolonged conflict, agreed to the deal. West Papuans were told nothing about the agreement; when news of it later spread, they launched the Free Papua Movement) to oppose the Indonesian government’s takeover. That movement continues to this day.

The New York Agreement also included a commitment to hold a plebiscite. In the so-called “Act of Free Choice,” all approximately 800,000 adult West Papuan men and women were supposed to be given the right to decide whether to become independent. However, in the actual 1969 vote, the Indonesian government handpicked 1,026 representatives and coerced those who favored independence from Indonesia. The result was a unanimous decision by the representatives against independence and to remain with Indonesia. Because the representatives were intimidated and not all West Papuans were allowed to vote, the referendum came to be known as the “Act of No Choice.”

Two years before this Act of No Choice, Freeport had already concluded talks with the Suharto regime and agreed to jointly develop the Ertsberg mine in West Papua. After the vote, Freeport, together with the Anglo-Australian mining company Rio Tinto (Rio Tinto), began developing the Grasberg mine. The Grasberg mine boasts the world’s largest gold output and the second-largest production of copper. In addition, companies like the UK’s BP and Japan’s Mitsubishi Group started operations one after another in West Papua. The Indonesian military reportedly maintained close ties with these major corporations and even engaged in illegal business activities.

After Annexation by Indonesia

Once West Papua became part of Indonesia, the parliament, flag, and Papuan anthem that had been prepared for independence were all banned. Even the name West Papua was changed to Irian Jaya, and the territory was turned into a military zone. The main beneficiaries of natural resources such as minerals and timber were foreign companies and the Indonesian government. To facilitate governance in their favor, large numbers of migrants were sent from other Indonesian islands, further heightening tensions with Indigenous people.

As noted, West Papua is extremely resource-rich and could well be a rapidly developing region. Nevertheless, it is considered the poorest area in Indonesia. While the national poverty rate is 11%, in West Papua it is above 25%, and as many as 35% of the population is illiterate. More than 55% of residents in West Papuan cities are migrants, yet the infant mortality rate among migrants from other islands is 4%, compared to 18% among Indigenous people. Conflicts between Indigenous residents and government officials or migrants are frequent, and discrimination against Indigenous people often triggers protests.

In addition to such discrimination, there have been repeated protests over environmental destruction caused by mining and deforestation, and armed resistance has grown alongside calls for independence.

In 1973, the West Papua National Liberation Army (West Papua National Liberation Army) was formed out of the Free Papua Movement and began armed resistance against the Indonesian government. A major incident was the 1984 attack on Jayapura, but it was quickly suppressed by the Indonesian military, which retaliated in turn. As a result, many Indigenous Papuans became refugees and were forced to flee to Papua New Guinea. Nevertheless, the Liberation Army’s activities continue. In December 2018, the Liberation Army attacked and killed more than 30 construction workers building a bridge. The group claimed the workers were Indonesian soldiers and justified the attack by saying the bridge was being built for the benefit of the police and government forces. In this way, intense acts of violence by both the Liberation Army and government forces and police have made the road to resolution extremely difficult.

In 1998, after President Suharto’s fall, the Indonesian government proposed several measures to try to address the West Papua issue. One was the 1999 Papua People’s Congress. The congress was supposed to function as a forum to resolve issues within Papua and to make policy proposals to the central government. Although President Abdurrahman Wahid did not support independence, he acknowledged that the Indonesian government bore responsibility for West Papua’s poverty and conflict and said West Papuans would be given an opportunity to voice their opinions. However, when the Congress declared independence in 2000, President Wahid revoked its approval and sent police and troops to West Papua. Outraged by the president’s actions, Indigenous Papuans attacked migrants from other islands, and the government used the military to suppress them—leading to fierce clashes. In 2001, when the representative of the Papua People’s Congress was assassinated by the Indonesian military, the independence movement appeared to calm down, at least temporarily.

In 2002, however, Free West Papua Campaign founder Benny Wenda was arrested on suspicion of leading an independence rally. According to Indonesian authorities, that rally turned violent and even resulted in the death of a police officer, but Wenda denied involvement, and it is said he was arrested for political reasons. He later escaped from detention, fled to Papua New Guinea, and a few months later obtained political asylum in the United Kingdom. He is currently based in the UK and serves as the chair of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua.

Benny Wenda (Photo: Richter Frank-Jurgen/Flickr [C.C. BY-SA 2.0])

Current State of the West Papua Issue

The problem continues to this day. Foreign media and NGOs are still largely barred from entering West Papua. Although President Joko Widodo lifted restrictions on foreign media in 2015, the grave situation remains unchanged. In 2014, the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (United Liberation Movement for West Papua) was launched, unifying three major movements seeking West Papuan independence. The group was able to join the Melanesian Spearhead Group (Melanesian Spearhead Group) as an observer. The Melanesian Spearhead Group is a regional organization of Melanesian countries formed in 1986, now comprising Fiji, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia. However, in 2015 Indonesia joined as an associate member, coming to represent the West Papuan region within the organization. Among these countries, Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea primarily support West Papua’s independence, but to maintain favorable trade relations with Indonesia, they have been unable, publicly at least, to give full support.

In 2017, Wenda submitted a petition to the UN Special Committee on Decolonization, calling for West Papua’s issues to be placed on the agenda and for an investigation into human rights abuses. Although about 1.8 million residents signed the petition, the committee chair decided the body had no mandate to discuss West Papua, and the UN promptly rejected it.

Papua, Mulia District (Photo: Frans Huby/Wikimedia [CC BY 3.0])

Since Indonesia’s annexation, protests by West Papuans have been frequent, and the demonstrations in September 2019 were by no means unprecedented. However, the scale this time was markedly different from before. Previously, protests involved only a few hundred people within the West Papua region, or were limited to activities by exiled leaders such as Wenda. This time, thousands of people protested, and not only West Papuans but Indonesians from other islands joined anti-discrimination movements, expanding the circle of those resisting unjust treatment.

Many West Papuans still seek a referendum on independence, but the Indonesian government firmly refuses. While President Widodo insists that riots and disruptions of social order will not be tolerated, he has shown some willingness to address the West Papua issue. Nevertheless, perhaps because West Papuans make up only 2% of Indonesia’s total population, the political interest surrounding them remains low, and the issue is undeniably being neglected.

Meanwhile, protests and riots by residents, as well as human rights violations by the government and police, continue. There have been many injuries and deaths, and there is no sign of the situation calming down. Even if a political solution remains distant, halting the tragic cycle of violence will require attention from outside West Papua and Indonesia.

Note 1: “West Papua” refers to the western part of New Guinea that belongs to Indonesia and includes the Papua and West Papua special provinces.

Note 2: Melanesia is one of the island groups scattered across the South Pacific. Together with Australia, Polynesia, and Micronesia, the region is known as Oceania.

Writer: Namie Wilson

Graphics: Yow Shuning

We share updates on social media too!

Follow us here ↓

国連やNGOも出入り出来ない状態となってくるとどうすればこの問題は解決していくのでしょうか。

実際にはHuman Rights Watch などのNGOはあらゆる手段で西パプアには入ろうとしています。

しかし、国連のように署名運動を認めないという現状が続いています。

この問題を解決するには、インドネシア政府と西パプア住民がしっかり話し合って協力することが大事になると思います。例えば、インドネシアのアチェ地域も独立運動もしていましたが、現在は自治体などができたので、独立運動は収まっています。西パプアもこのような状態になるのが一番現実的かもしれません。

西パプアがそのような状態になっていると初めて知りました。西パプア、インドネシアの外からの注目も必要であるのに、国連やNGOも出入りできない状態ではこの問題の解決は難しそうですね。

ただのデモで40人近くの死亡者も出るなんて、パプア人がかわいそう。

西パプアには豊富な資源があるにもかかわらず、インドネシアで一番貧しい地域であるのはとても不平等だと思った。

ウェンダ氏が提出した歎願書が国連の委員会の委員長に「議論する権限がない」として却下されたという事実は、国連が国という構成員でできているゆえ利害が絡むと途端に機能しなくなるという現実をきれいに表しているなと感じました。新たな国連の体制を模索しなければならないと痛感します。