In May 2021, natural gas production at the Bayu-Undan oil and gas field off Timor-Leste entered a new phase of drilling. Timor-Leste had already been developing this field and has earned substantial revenue. In fact, since independence a large share of the nation’s income has come from the oil and gas sector, and it has heavily relied on it. As the global push for “decarbonization” advances, attention has also focused on relations with neighboring Australia over extraction rights and on how the government will use this finite resource. This article considers the future of Timor-Leste.

A tanker transporting natural gas extracted in the Timor Sea for export from Australia to Japan (Geoff Whalan / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

History of Timor-Leste

Timor-Leste is located in the eastern part of Timor Island, north of the Australian continent, and borders Indonesia, which controls the island’s western half.

Before the 16th century, multiple kingdoms existed in Timor-Leste. In the 16th century, ships from Portugal arrived in search of sandalwood, and the area later came under Portuguese rule. During World War II it was occupied by Japan, and after the war Portugal resumed control. In 1974, a coup in Portugal toppled the regime that had pursued colonial rule, and Portugal gradually loosened its control over Timor-Leste. The following year, 1975, amid a rising independence movement, pro-independence groups including the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (FRETILIN) declared independence. However, Indonesia invaded, and the territory was annexed the following year as its 27th province. The United Nations did not recognize this annexation by Indonesia and recognized Portugal’s legal administrative authority. Thereafter, the independence movement—centered on FRETILIN—continued, and in efforts to suppress it, Indonesian forces committed crimes against humanity, including massacres and killings.

In 1998, widespread civil protests erupted in Indonesia over the government’s response to the Asian financial crisis, bringing down the regime. The new government that followed agreed to a referendum on Timor’s independence. In 1999, the UN Security Council established the United Nations Mission in East Timor (UNAMET), which conducted a referendum on independence. As a result, about 80% of residents chose “separation/independence.” Voter turnout reached 98.6%, showing how strong public interest in independence was.

Immediately after the vote, however, acts of destruction and violence by anti-independence forces surged, forcing UNAMET to withdraw from Timor-Leste. These riots are believed to have been linked to various operations carried out by the Indonesian military before and after the referendum, raising suspicions that Indonesia sought to prevent Timor-Leste’s independence. In response to this instability, in 1999 the Security Council decided to establish a multinational force (INTERFET) and the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET), and the UN temporarily administered Timor-Leste. Twenty-seven years after the 1975 declaration of independence, in 2002 Timor-Leste formally became an independent state. The first president (※1) was Xanana Gusmão, and the first prime minister was Mari Alkatiri, then leader of the ruling party FRETILIN. Both had been central to the independence movement since the 1970s, and both belonged to FRETILIN at the time of the 1975 independence declaration.

Left: Mari Alkatiri (World Bank Photo Collection / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Right: Xanana Gusmão (World Trade Organization / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Although both men worked energetically for independence, after Mr. Gusmão left FRETILIN in the 1980s, tensions gradually grew between them. In 2006, soldiers dismissed by Prime Minister Alkatiri staged a riot demanding his resignation, and he stepped down. The fact that President Gusmão at the time demanded Alkatiri’s resignation also underscores their rivalry. In 2007, Mr. Gusmão founded the National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction (CNRT), which became the second-largest party in parliament, and he became prime minister, consolidating power. Around 2012, however, Mr. Gusmão named a figure from the rival FRETILIN as his successor for prime minister, improving his relationship with Mr. Alkatiri and bringing greater domestic stability. This is seen as part of Mr. Gusmão’s plan to hand over power from the independence-era generation to younger politicians. Ultimately, in 2017 Mr. Alkatiri returned as prime minister, forming a short-lived nine-month government. A coalition government led by Mr. Gusmão’s CNRT subsequently took office, but since 2020 another coalition centered on FRETILIN has been in power.

Development of natural resources

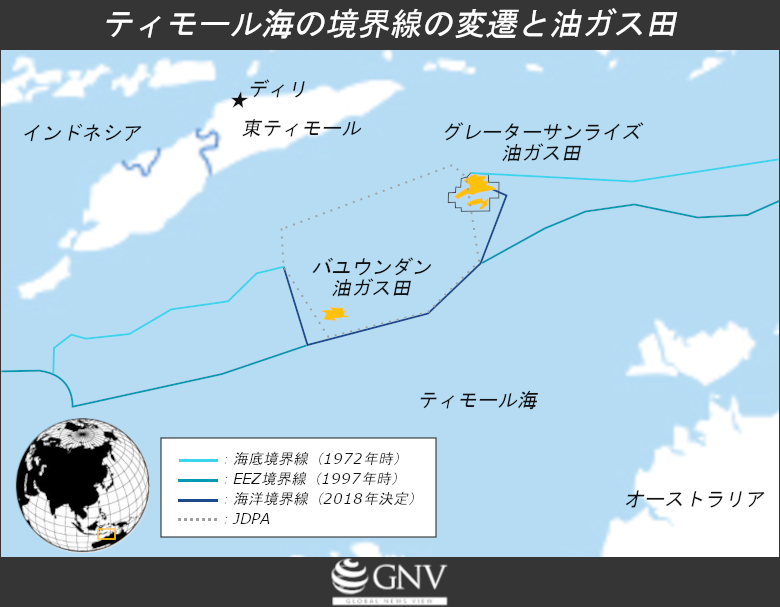

The Timor Sea to the south of Timor Island contains hydrocarbons such as oil and gas and has been developed over the years. To understand the history of the Timor Sea’s natural resources, we look back at the key arrangements. Until Timor-Leste’s independence, agreements over the Timor Sea were made primarily between Australia and Indonesia. The first agreement between these two countries was the seabed boundary treaty of 1972. It later emerged, however, that the treaty left an undemarcated area known as the “Timor Gap.” In 1989, the two countries signed the Timor Gap Treaty, designating the “Timor Gap” as a Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA) to be jointly developed. Portugal, which the UN still recognized as having administrative authority, brought a case against Australia at the International Court of Justice, claiming its administrative rights and Timor-Leste’s right to self-determination had been violated, but the court dismissed Portugal’s claims. Some observers argue the court issued a restrained judgment because the dispute also concerned the interests of a third country, Indonesia . While seabed boundaries had been addressed, the maritime boundaries remained unsettled. Thus, in 1997 Australia and Indonesia concluded the Perth Treaty to delimit their respective exclusive economic zones.

When Timor-Leste formally became independent in 2002, it signed the Timor Sea Treaty with Australia. Replacing the 1989 Timor Gap Treaty, it set a new revenue split for oil produced from the JPDA and carried forward the boundaries of the Perth Treaty. The JPDA contains major fields including Bayu-Undan and part of the Greater Sunrise field, and the revenue split from oil produced there was set at Timor-Leste:Australia = 9:1. At the same time, the treaty gave Australia jurisdiction over the pipeline from the Bayu-Undan field to Darwin in northern Australia, and Australian companies began producing liquefied natural gas (LNG). Because the treaty did not address LNG, Australian companies with capital and technology captured the profits from LNG. Furthermore, the treaty placed 79.9% of the Greater Sunrise field—discovered back in 1974—within Australia’s exclusive economic zone as defined by the Perth Treaty, with the remaining 20.1% inside the JPDA. Thus, Timor-Leste’s share of profits from Greater Sunrise was 90% of the 20.1% portion located in the JPDA, or about 18% of the whole. In other words, while the JPDA revenue split appeared favorable to Timor-Leste, its actual share from one of the main fields, Greater Sunrise, was small.

Australia’s claimed exclusive economic zone is aligned with the continental shelf and lies closer to Timor-Leste than the midline that Timor-Leste claims. Unwilling to accept this, Timor-Leste continued negotiations with Australia, and in 2006 the two countries signed the Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS). This set the Greater Sunrise revenue split at Timor-Leste:Australia = 5:5. It also deferred any decision on the maritime boundary for the next 50 years.

In 2013, Timor-Leste reached a turning point: it was revealed that Australia had conducted spying during the CMATS negotiations, including bugging key government facilities such as the prime minister’s office in Timor-Leste. Timor-Leste took the matter to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), and compulsory conciliation was initiated. CMATS was annulled, and in 2018 the two countries concluded a new Timor Sea treaty determining the revenue split from Greater Sunrise. Timor-Leste’s share depends on where the gas is piped: it would receive 70% if the gas is sent to Timor-Leste, or 80% if sent to Australia. The treaty also abolished the JPDA, set the maritime boundary at the median line between Timor-Leste and Australia, and granted Timor-Leste all revenues from the former JPDA area, including the Bayu-Undan field. Even so, actual extraction is carried out by international oil companies from the United States and Australia, and capital continues to flow out of the country.

A government building in the capital, Dili (David Stanley / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

As we have seen, since independence Timor-Leste has sought to secure its interests through repeated negotiations and treaties despite an unfavorable power balance with regional power Australia. Nevertheless, many aspects of the revenue sources lying under the sea remain uncertain. The 2018 maritime boundary treaty has several issues. First, although Timor-Leste negotiated boundaries and revenue sharing with Australia, it has not clarified the boundary and revenue split with neighboring Indonesia—potentially inviting new friction. Second, regulations governing marine environmental management in this region remain unclear, raising concerns about potential environmental damage from future oil and gas development. Third, while the treaty provides that all revenues from oil fields in the former JPDA accrue to Timor-Leste, Australia delayed ratification. In fact, although the treaty was signed in March 2018, Australia did not ratify it until July the following year. During that time, Australia continued to receive 10% of JPDA revenues under the more favorable 2002 Timor Sea Treaty. The total is said to amount to US$5 billion. Although some, including Australian politicians, have called for compensation, it has not been repaid.

Moreover, as noted at the outset, there is a global move toward “decarbonization,” and the prospects for Timor-Leste—whose national revenue relies heavily on fossil fuels—are themselves uncertain. In 2016 and 2017, about 90% of national revenue came from the oil and gas sector, an extreme monoculture economy. Although advances in technology have increased extractable oil and gas reserves, it is widely understood that these resources will eventually be depleted. Currently, Timor-Leste deposits all oil and gas revenue into a Petroleum Fund established in 2005 and transfers necessary amounts to the national budget to ensure sustainable use of these revenues. In the early years, there were notable results in rural electrification and infrastructure investment.

However, resources at the Bayu-Undan field were expected to be depleted by 2023, and under the current spending approach, the fund balance of US$19 billion could be exhausted as early as 2030. This has heightened the urgency of developing the Greater Sunrise field. Mr. Gusmão has long argued against piping gas to Australia for processing and instead proposes building an LNG export facility on Timor-Leste’s coast. However, Timor-Leste faces difficulties raising funds for this facility, and both Mr. Gusmão’s project and the development of Greater Sunrise itself have stalled.

People protesting Australia’s claims (Andrew Mercer / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Economy-wide challenges

Timor-Leste experienced oppression and conflict under neighboring Indonesia immediately after emerging from colonial rule, and there was considerable turmoil before formal independence. Much domestic infrastructure was destroyed and many people were displaced. Although reconstruction began around 2007, the effects remain. At that time, due to devastated lands, even staples such as rice had to be imported. While the country focused on cultivating coffee as an export crop and has increased its production year by year, it still cannot replace oil and gas as the mainstay. In short, Timor-Leste has struggled to advance national “development” as intended.

Abundant oil and gas resources have provided a foundation for economic development in the face of political and economic difficulties. To avoid the so-called “resource curse” (※2)—where resource-rich countries tend to have less diversified industries and struggle to sustain economic growth and democracy—Timor-Leste established a petroleum fund, following the example of Norway, and has invested proceeds into it, as noted above. However, because oil and gas extraction is carried out by foreign companies with capital and technology, much of the wealth from these resources has flowed out of the country. Moreover, despite earning revenue from natural resources, its use has been problematic. In practice, capital from natural resources has not been sufficiently directed to the agricultural sector—which employs about 66% of households—or to education and health for the country’s children.

So where has the government spent the income from natural resources? Much of it has gone into two industrialization projects promoted by the two powerbrokers who have held real power since the independence era and still do today, reflecting their political rivalry. The first is a large-scale infrastructure investment led by former Prime Minister Alkatiri to build ports, roads, and public facilities in the enclave Oe-Cusse Special Administrative Region and turn it into an industrial zone. The second is the so-called Tasi Mane Project promoted by Mr. Gusmão, involving an onshore natural gas processing plant and associated port and road development—a massive undertaking requiring US$18 billion.

Workers engaged in infrastructure development (ILO Asia-Pacific / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

These two projects share a common criticism: the benefits do not justify the scale of investment. The Tasi Mane Project in particular faces several issues. First, there are economic and technical challenges in developing the pipeline to transport gas onshore. The project also requires skilled workers, but Timor-Leste faces a shortage of such personnel, meaning workers will be sourced from abroad and employment gains within Timor-Leste will be limited. There is also testimony that compensation is inadequate for residents adversely affected by the development. Furthermore, neither the Oe-Cusse industrial zone project nor the Tasi Mane Project can be financed solely by the Petroleum Fund and the national budget. The government is thus seeking to raise funds from overseas, mainly Chinese banks, but some warn this could lead to a debt trap. For these reasons, many see the projects as driven by political vanity and likely to fail.

For Timor-Leste to stabilize its future without relying on oil and gas, growth in other sectors—that is, economic diversification—is necessary, but progress has been limited. There are several reasons. One is political. First, political disharmony is a factor: in just over 18 years since independence there have been 8 different governments, each serving a short term. With little prospect of long-term stability, governing parties tend to adopt short-term measures to maintain power rather than make long-term strategic investments . Policies have tended to focus on highly visible initiatives like large-scale infrastructure investment, and the huge funds poured into them have been sourced from the still-profitable oil and gas sector. Because oil and gas offer immediate returns, investment in other sectors that take longer to yield profits is often deferred. This is evident in the megaprojects noted above and perpetuates dependence on oil and gas. Structurally, the two main parties—CNRT and FRETILIN—often disagree on policies to address national priorities. While the broad outline of national development is based on the Strategic Development Plan (SDP), the parties differ greatly in how to realize it. For example, as noted, Mr. Gusmão, influential in CNRT, and Mr. Alkatiri, influential in FRETILIN, each promote their own large-scale development projects. A second reason diversification has lagged is the long-standing problem of poverty. Due to political instability and uneven redistribution of resources, an estimated 45.8% of the population is in multidimensional poverty (※3), hindering the ability of individuals to invest and start new businesses.

A boy pushing a handcart (Asian Development Bank / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

As discussed, Timor-Leste’s finances are heavily dependent on the oil and gas sector, which has also constrained economic growth. The resulting economic issues ultimately burden citizens in the form of poverty. In 2016, about 40% of the population lived on less than US$1 per day; in 2020, 47% of children under five were malnourished; and, as noted, multidimensional poverty is an issue. GDP per capita in 2020 was US$1,359, ranking 160th out of 194 countries surveyed, far from affluent. The unemployment rate among those aged 15–34 is around 60%, making it difficult to say that stable employment is assured.

Where Timor-Leste is headed

In August 2020, the government of Timor-Leste released an Economic Recovery Plan (ERP) detailing measures to minimize further economic slowdown due to COVID-19 and to enable medium- to long-term recovery. In addition to proposing improvements in productive sectors to diversify the economy, it places human development at the heart of economic policy and recommends improving education as the core long-term strategy for economic development.

Every country develops by leveraging its geographic and historical conditions, climate, and resources. Timor-Leste, in particular, has a history of disadvantage: after Portuguese rule ended, it was invaded by Indonesia, and even after independence it had to confront a regional power, Australia, seeking its own interests. Despite this, the country has sought development by extracting and exporting oil and gas—resources in global demand. Yet as seen in the push for “decarbonization,” the energy sector worldwide is at a major turning point, and Timor-Leste likewise needs to transform its industries. Internal political factors—where differing views should be reconciled to pursue short- and long-term national development and stability—and external factors, such as interventions by other countries, have hindered this transition. Timor-Leste’s future does not lie only beneath the seabed. Where will Timor-Leste look next? We will be watching.

People walking in downtown Dili, the capital (Asian Development Bank / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

※1 In Timor-Leste, the president has a ceremonial role, and real power lies with the prime minister, who is chosen by parliament.

※2 Resource curse: the tendency for resource-rich countries to suffer more from poverty and lagging economic development than those without such resources. A primary reason is that concentrating national capital and labor in the resource extraction sector destabilizes the economy and hinders development in other areas.

※3 Multidimensional poverty: overlapping deprivations across three dimensions—health, education, and income. The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) capturing incidence and intensity at the household level is reported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Writer: Yosuke Asada

Graphics: Mayuko Hanafusa

政府が国民へのアピールのために巨額のインフラ投資を行っているとあったが、実際に国民はそういった政府の予算の使い方に満足しているのか気になった。

天然資源に依存している国は、今後どうなっていくのか、、、目が離せないと思いました。

記事中で様々な原因に触れられていますが、国の収入を石油などの資源に頼っているにもかかわらず、約66%が農業に従事しているということからも資本流出と貧困の深刻さがうかがえました。

モノカルチャー経済の克服には政治的安定が必要であることについて、政治(家)に対する市民の声は必須だと思いますが、およそ半数の人々が貧困状態にある状況ではそのような動きも難しい気がして…これからどうなっていくのでしょうか…。