Despite remarkable economic development and technological advances, poverty remains deeply entrenched around the world and continues to be a major global challenge. Many readers of this article have likely studied global poverty, supported fundraising or donations for people in need, participated in volunteer activities, or at least take an interest in global poverty. Our perceptions of global poverty are, in large part, shaped by facts reported in the media, because we generally learn about the reality of global poverty not by traveling to the field ourselves, but primarily through media coverage. Thus, the way poverty is reported is a crucial key to how it is perceived. But does reporting in Japan truly reflect the realities of global poverty? This article seeks to explore that question.

What exactly does “poverty” refer to? Poverty has two concepts: absolute poverty and relative poverty. Absolute poverty refers to a state of extreme deprivation in which levels of income, health, education, and other essentials are so low that minimum living standards are not met. The World Bank sets a benchmark for absolute poverty known as the “international poverty line,” which is currently defined as living on less than $1.90 per day. Poverty is a highly complex phenomenon, and expressing it in monetary terms does not necessarily capture the whole reality, but this benchmark provides a guideline for grasping the global situation. Relative poverty, on the other hand, refers to having a significantly lower income compared to the average standard of living in a given society. In this article, we focus on absolute poverty.

Let us look at the current state of global poverty. In July 2015, the Millennium Development Goals Report was released at UN Headquarters. The report reviewed progress toward the “Millennium Development Goals” established to eradicate poverty. It showed that global poverty has improved, while also pointing out remaining challenges.

According to the report, between 1990 and 2015 the share of people in developing countries living in extreme poverty—defined at the time as less than $1.25 per day (hereafter, the “extreme poor”)—fell from 47% to 14%. Globally, the share of the extreme poor declined from 36% to 12%, and in absolute numbers from about 1.9 billion to about 800 million. In most regions, the share of the extreme poor was cut in half or more. However, there are criticisms that a large part of poverty reduction was driven by economic growth in populous countries like China and India, and that there are major issues with the statistics underlying the report. Moreover, among the figures released, Sub-Saharan Africa was the only region that did not see the share of the extreme poor reduced by half. The report also showed that around 80% of the global extreme poor are concentrated in two regions: South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, nearly 60% of the world’s extreme poor are found in the five countries with the largest extreme-poor populations (India, Nigeria, China, Bangladesh, the Democratic Republic of the Congo) (as of 2011). In addition to all this, there is the major challenge that inequality is widening globally.

Thus, while there are signs of improvement in global poverty, poverty remains highly uneven across regions, and there are still many challenges that must be addressed. Are we, in fact, receiving sufficient information about this global reality?

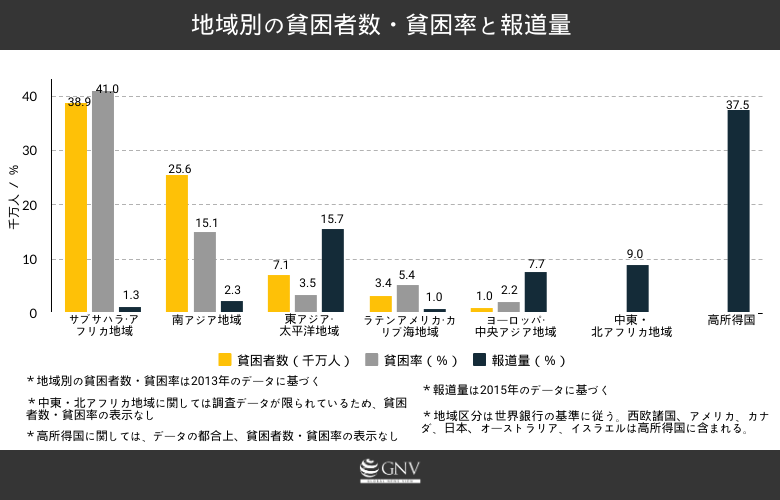

The graph below shows the number of poor people and the poverty rate by region (poverty line: less than $1.90 per day), along with the volume of media coverage. Data on global poverty are from the World Bank. As for coverage volume, GNV independently collected international reporting data from three national newspapers (Asahi, Yomiuri, Mainichi) for 2015, calculated each paper’s coverage volume based on character counts, and then averaged the three to obtain regional shares.

The number of poor people and poverty rate by region are based on World Bank data

As the graph above shows, the share of coverage devoted to regions where poverty is severe, such as Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, is low, whereas coverage of high-income, wealthy countries is strikingly high. In Japan’s international reporting, coverage is concentrated in regions where wealth is concentrated, and regions with high poverty are neglected.

Incidentally, in the 2015 international reporting of the three national dailies, the proportion of articles whose headlines included the character for “poverty” (貧) or words such as hunger, famine, or destitution—thus emphasizing that they were reports about poverty—was: Asahi: 0.28%, Yomiuri: 0.18%, Mainichi: 0.34%. When we combine the extracted articles from the 3 papers and look at the regional breakdown of coverage, we get: Europe: 22.9%, Middle East: 18.8%, Asia (excluding the Middle East): 12.5%, Africa: 12.5%, Latin America and the Caribbean: 10.4%, North America: 0%, World as a whole: 22.9%. With the exception of North America, the regional shares are not extremely disparate, but coverage of Europe—a region with low poverty rates—is higher than for any other region. As one example, there was a piece on France: “Shaken Tricolore: Three Months After the Attack on the French Weekly / Part Two — Entrenched Poor Neighborhoods, Immigrant Concentration, ‘Turned Away from Jobs Based on Address’” (Mainichi Shimbun, 2015/4/11). It is doubtful that the realities in regions where poverty is severe are being sufficiently conveyed.

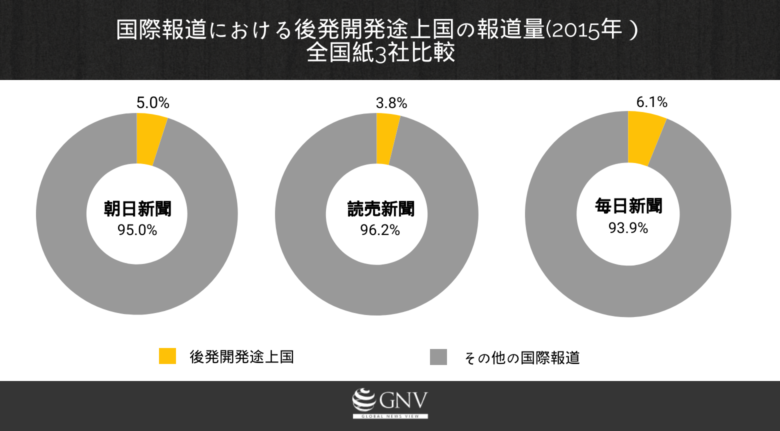

Next, let us look at the results of an analysis focusing on the countries related to each article. Here, “related countries” refers to a criterion independently defined by GNV, whereby countries are deemed related based on the wording of the headline or the location of the event. We extracted articles in which Least Developed Countries (LDCs) were related countries and analyzed the volume of reporting on LDCs. LDCs are a UN classification denoting the countries lagging furthest behind in development among developing countries. As of February 2016, 48 countries were designated as LDCs, about 1 in 4 globally. Here too, we calculated coverage volume from the three national dailies’ international reporting in 2015 based on character counts. The graph below shows reporting volume on LDCs.

For all 3 papers, the share of reporting devoted to LDCs is low, averaging about 5%. Although LDCs account for roughly 1/4 of the world’s countries, their share in international reporting is only about 1/20. Clearly, the balance between global poverty realities and reporting is skewed. A regional breakdown also yields interesting results. Averaging the three papers’ regional coverage of LDCs: Asia (9 countries): 4.2%, Africa (34 countries): 0.59%, Oceania (4 countries): 0.1%, Latin America and the Caribbean (1 country): 0.003%. Of the 48 LDCs, 34 are in Africa, yet coverage of these 34 countries amounts to only 0.59% of all international reporting. By contrast, the 9 LDCs in Asia account for 4.2%. Even more strikingly, over the entire year 2015, there were 11 African LDCs that were not covered even once by any of the 3 papers. In other regions, there were no countries that went entirely uncovered by all three. As these results also show, the balance between poverty realities and reporting is badly distorted—information on African countries, where extreme poverty is particularly severe, is largely shut out.

As we have seen, there is a clear gap between the current state of global poverty and the reality of its reporting. Because much attention is paid to regions with milder poverty or where poverty has improved substantially, are we not becoming somewhat optimistic about global poverty? For regions where poverty is severe, the volume of coverage is small, and important facts may be disappearing from view. Even if poverty is being reduced globally, many people still suffer from it, and we cannot afford to be complacent.

We obtain most information about global poverty from media coverage. In other words, our understanding of poverty is largely shaped by the media. The media are therefore expected to report on poverty more objectively and comprehensively, but as this analysis shows, the information most readily available to us is quite limited and biased. With such unbalanced reporting, we may form a vague image of poverty, but we cannot understand its current state or causes. Moreover, there are very few opportunities to learn about or reflect on how we influence global poverty and how global poverty affects us. To talk about poverty under such conditions is premature and perilous. This applies not only to poverty but to any kind of reporting. We must maintain a stance of engaging with information while being mindful of both the facts presented and the facts omitted, and we should once again urgently re-examine international reporting in Japan.

Writer: Taihei Toda

Graphics: Taihei Toda

0 Comments