Bashar al-Assad, Syria’s long-time leader, was toppled in December 2024 by a rebel coalition led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). HTS grew primarily out of the Nusra Front, al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate, and was formally established in 2017. A report by a United Nations Security Council committee as of July 2024 described HTS as “the most prominent terrorist organization in northwestern Syria.” It had also been designated a terrorist organization by multiple countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom. Its leader at the time, known by the nom de guerre Abu Mohammed al-Jawlani, was under sanctions by the UN Security Council. The U.S. government had also placed a $10 million reward for information on him.

HTS’s 2024 overthrow of the Syrian government led to a significant rebranding of the group and its leader. Al-Jawlani swapped his previously militant attire for Western-style clothing, changed his name to Ahmed al-Sharaa, and adopted positions aligned with Western interests. This suggested he could be accepted as Syria’s new leader. In July 2025, the United States revoked HTS’s terrorist designation. Meanwhile, HTS remains on the UK list of proscribed terrorist organizations, yet the British foreign secretary visited Syria to meet its leader.

On July 5, 2025, on the same day the British foreign secretary visited Syria, the home secretary designated a group called Palestine Action as a terrorist organization. Palestine Action is a protest group whose aim is to “end global complicity in Israel’s genocide and apartheid regime,” and it had been active mainly targeting the “Israeli military-industrial complex.” The designation followed an incident in which its members broke into a UK military base and sprayed red paint on two military aircraft in protest of support for Israel. With the designation, the UK’s counterterrorism law made statements or acts supporting Palestine Action crimes in themselves. During demonstrations protesting the designation, 890 people were arrested under the same law.

These two cases highlight how inconsistently and flexibly governments apply the concept of “terrorism,” prompting us to ask what “terror” actually means. This article delves into the concept of “terrorism” itself and considers its meanings and how it is perceived.

Ahmed al-Sharaa of Syria meeting with the Saudi crown prince and the U.S. president (Photo: White House / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain] )

目次

Definitions

Given that the word “terror” appears to be used arbitrarily, it is worth examining several definitions to understand what it actually means.

Oxford Reference offers a typical dictionary definition: “the use of violence, or the threat of violence, planned to instill fear. Terrorism is generally intended to intimidate or coerce governments or societies, often for political, religious, or ideological purposes.” A 2004 report by the UN High-Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change defined terrorism as: “any action, in addition to actions already specified by the existing conventions on aspects of terrorism, that is intended to cause death or serious bodily injury to civilians or non-combatants, when the purpose of such an act, by its nature or context, is to intimidate a population, or to compel a government or an international organization to do or abstain from doing any act.”

These definitions share common elements widely agreed to constitute “terrorism”: violence (or threats of violence) against civilians or non-combatants, the intent to intimidate, and the pursuit of some objective. Researchers who study terrorism also largely agree on these core elements (※1).

However, such definitions are not universally accepted. National governments craft their own legal definitions of “terror,” and specific government agencies also use their own. These definitions can expand—or conversely narrow—the range of acts considered “terror.”

Woman arrested under UK terrorism laws for expressing support for Palestine Action (Photo: Alisdare Hickson / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0] )

For example, the UK’s Terrorism Act 2000 provides that not only attacks on civilians but also “serious damage to property” can be classified as terrorist acts. With such a broad definition, the UK government can prosecute the spraying of paint on parked military aircraft not as mere criminal damage but as a “terrorist act.” By contrast, the U.S. State Department’s definition limits “terrorism” to acts perpetrated by non-state actors. Thus, even if a government (including the U.S. government) carried out killings to intimidate civilians for political purposes, under this definition such acts would not be officially considered “terrorism.”

Further definitional issues arise when attempting to classify specific groups as “terrorist organizations.” Such labels often carry the image that these groups engage exclusively in terrorist acts. As a result, observers may be puzzled or surprised when organizations labeled “terrorist” are involved in conventional armed conflict or routine governance activities akin to those of states. The reverse is also common: groups regarded as state armed forces or traditional insurgents sometimes carry out actions that deliberately target and intimidate civilians—acts that can be considered terrorism—under certain conditions. For example, the exploding pagers incident Israel used in Lebanon in 2024 is a clear case.

Terror is best understood not as a label attached to a particular organization but as a term referring to a type of act. In fact, in many armed conflicts the boundary between the use of force and terrorist acts is highly blurred.

Political labeling

In everyday contexts, the term “terrorism” tends to be used in highly subjective and political ways. Whether a group or act is labeled “terror” in government statements or media coverage often depends on the political and strategic aims of powerful countries. One scholar notes that the term is used by governments and others to demonize those they regard as enemies—or, more simply, to refer to “violence one does not support.” A famous saying holds that “one person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter.”

Nelson Mandela and former Secretary-General Kofi Annan (2013) (Photo: UNIS Vienna / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0] )

As noted above, the official “terrorist” designation for Syria’s HTS and its leader changed rapidly with shifts in U.S. political priorities. But that was not the case with South Africa’s Nelson Mandela. Mandela was an anti-apartheid activist and member of the African National Congress (ANC), later serving as the first president of post-apartheid South Africa in the 1990s. He was imprisoned from 1962 to 1990, primarily on charges related to sabotage and conspiracy aimed at overthrowing the apartheid regime. The U.S. government viewed Mandela as sympathetic to communist ideas and reportedly helped his arrest through a CIA tip-off, as reported. Thereafter, because of ANC sabotage against the South African government, Mandela’s name was placed on the U.S. terrorist watch list. It was not removed until 2008.

In some cases, whether an act is treated as terrorism depends less on the act or intent itself and more on the religious ideology associated with the perpetrator. For example, in Norway in 2011, a self-declared Christian nationalist carried out a series of attacks, including the bombing of the prime minister’s office and a massacre of youths at a Labour Party summer camp, killing 77 people.

Many outlets initially speculated—without evidence—that Islamist extremists were responsible, only to be forced to correct themselves when the actual perpetrator became known. A New York Times article initially wrote that “there was ample reason to suspect terrorists were responsible.” In other words, once the perpetrator’s identity became clear, it read as though he was no longer a “terrorist.” Because the perpetrator was a Christian extremist rather than an Islamist extremist, the acts were suggested to be “extremism” rather than “terrorism.”

State involvement in terrorism: the United States

Given that the concept of terrorism is flexibly employed to serve particular political and strategic ends, the United States offers a revealing case study of how the term is used. The U.S. is known as the victim of a major terrorist attack on September 11, 2001 (9/11), which killed about 3,000 people. Since then, the U.S. has consistently positioned itself as the global leader in counterterrorism and declared a worldwide “war on terror.” From the outset, however, this “war” was questioned both logically and practically. Wars are waged against clearly defined enemies such as specific states or organizations, whereas terrorism is a tactic or method of violence rather than a fixed adversary, making it hard to understand how the concept applies.

Shock and awe. The U.S. invasion of Iraq, 2003 (Photo: 4WardEverUK / Flickr [CC BY 2.0] )

Moreover, the U.S. has long been accused of supporting or engaging in terrorism. There are many instances around the world in which U.S.-backed groups carried out terrorist acts. In the 1980s, for example, the U.S. provided military support to insurgents or governments involved in terrorism in Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Angola, among others. Regarding the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) in the former Yugoslavia, the U.S. provided military support in 1998 and 1999, though officials sometimes referred to the group as a terrorist organization. In 2012, while the U.S. was backing groups seeking to overthrow the Syrian government, Jake Sullivan, then deputy chief of staff at the State Department, emailed Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that al-Qaeda was “on our side in Syria,” according to an email.

The U.S. government has also directly engaged in actions that can be defined as terrorism. Most notably, the 2003 invasion of Iraq was carried out under the doctrine of “shock and awe (rapid dominance),” first proposed in 1996. Shock and awe is defined as “actions that create fears, dangers, and destruction beyond comprehension to the populace at large and to special groups or leadership.” In other words, it aims to instill fear in a target society through overwhelming force. The invasion of Iraq was executed under this doctrine; during the initial six weeks of massive airstrikes, an estimated 7,400 civilians were killed.

Ironically, the U.S. framed this invasion as part of the so-called “war on terror.” Since the start of this “war,” the death toll from five conflicts involving the U.S. between 2001 and 2022 is estimated at 4.5 to 4.7 million people (estimate) (※2).

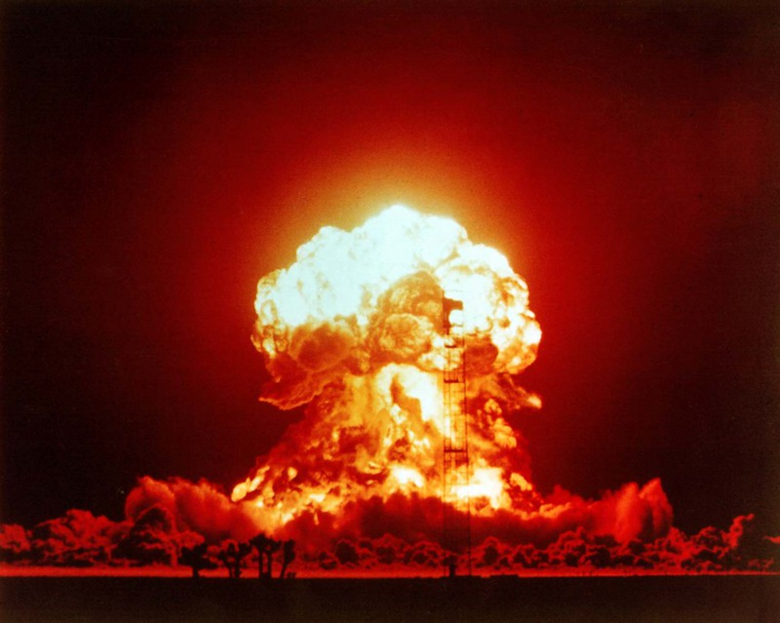

Nuclear weapons: the ultimate form of terror?

The architects of the U.S. military’s shock and awe doctrine regard the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as the “ultimate military application” of shock and awe. They argue that using these weapons “inflicts immediate, nearly incomprehensible levels of massive destruction on entire societies, both leaders and the populace.” These actions aim to “strike directly at the will of the enemy nation’s people to resist.” This description—mass killing of civilians to break their will—meets all the major elements of commonly accepted definitions of terrorism.

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) in a launch silo (Photo: Steve Jurvetson / Flickr [CC BY 2.0] )

The sheer scale of destruction these weapons cause further indicates that nuclear weapons are designed primarily for use against civilians rather than military targets. The atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima killed over 100,000 people. Since then, nuclear-armed states have vastly increased the destructive power of their arsenals. Today, the average yield of U.S. nuclear weapons is more than ten times that of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Some nuclear-armed countries have developed so-called “tactical nuclear weapons,” a term suggesting weapons more tailored to military purposes than to targeting civilians. Yet, depending on where they are used, tactical nuclear weapons can kill tens of thousands of civilians even with yields far below the Hiroshima bomb—far beyond the killing capacity of conventional terrorism. Moreover, most simulations of major nuclear powers using tactical nuclear weapons foresee retaliation and escalation that could cost tens of millions of lives within hours.

The “use” of nuclear weapons does not only mean launching them at and detonating them over enemy cities. Nuclear weapons are used routinely as “deterrents.” Deterrence entails an implicit threat to potential aggressors that, if they attack, there is both the will and the capability to kill hundreds of thousands of civilians in the aggressor’s country in retaliation. The most extreme version of deterrence is known as “mutually assured destruction” (MAD). Under this strategy, rival states build up their nuclear arsenals to levels capable of wiping out the opposing population—and potentially all life on Earth. Because both sides assume massive retaliation, each is expected to refrain from initiating a first strike.

This deterrence is not merely theoretical. To maintain a level of deterrence seen as credible to potential adversaries, nuclear-armed states must demonstrate both the technical capacity and the political will to carry out devastating strikes that would inevitably target civilians. Hence, even though no nuclear weapon has been detonated against an enemy since 1945, countries continue to invest vast sums in modernizing and improving their nuclear arsenals. Despite numerous studies suggesting that nuclear deterrence is not necessarily an effective strategy, states are strengthening their nuclear capabilities under this doctrine.

Nuclear test, United States, 1953 (Photo: International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0] )

As noted earlier, major definitions of terrorism include not only actual violence but also threats of violence against civilians. Nuclear deterrence functions as the most severe threat of violence against civilians currently conceivable. Accordingly, countries that possess nuclear weapons—and those that rely on allies’ so-called “nuclear umbrellas”—can be said to be engaged in terrorism.

The gap between media portrayals and reality

Much of the discussion above is clearly not reflected in the information provided by Japan’s major media.

In general, the perspective that acts by state actors can be considered terrorism is rarely taken into account—meaning definitions closer to that of the U.S. government are often adopted rather than those used by the UN. During the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, mainstream media offered no articles considering whether the U.S. “shock and awe” campaign could be seen as terrorism—and such arguments have not been raised since. Meanwhile, in looking back at the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks in the U.S., many outlets have continued to frame the invasion of Iraq as part of America’s “war on terror.” This framing persists despite the long-established fact that suggestions linking 9/11 to the Iraq invasion were falsehoods deliberately spread by U.S. officials at the time.

Nor is there any sign that Japanese media have grappled with the idea that the use of nuclear weapons or nuclear deterrence could be regarded as terrorism. In coverage of the relationship between terrorism and nuclear weapons, mentions are almost exclusively limited to the risks of such weapons falling into the hands of non-state extremist groups. In recent years, television programs on nuclear armament and nuclear deterrence have increased. These programs discuss the costs, benefits, and risks of nuclear armament and deterrence, but they generally do not address their relationship to terrorism.

HTS fighters storming a Syrian village (Photo: Qasioun News Agency / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 3.0] )

Even regarding violent terrorist incidents actually perpetrated by non-state actors, the media significantly distort their scale and where they occur. Of those killed in terrorist attacks worldwide in 2024, more than half were in West Africa, particularly the central Sahel. Yet this reality is scarcely reflected in Japanese media coverage of terrorism, which more often focuses on relatively small-scale incidents in Europe and North America.

Such tendencies have been investigated and reported by GNV in the past. They reflect a broader distortion seen across international reporting, stemming from a structure in which news organizations focus intensely on centers of power and wealth and tailor coverage to those perspectives. As a result, the viewpoints and priorities of the Japanese government and powerful Western governments are more likely to be strongly reflected in reporting on terrorism. Meanwhile, terrorism in regions far from the centers of power and wealth remains largely unreported.

Now is the time to step back and reconsider “what terrorism is” from a broader perspective.

※1 For example, in the definition proposed by Timothy Shanahan, terrorism is “the act of causing or threatening strategically indiscriminate harm to members of a target population to affect the psychological state of an audience population in ways the perpetrator expects will advance his/her goals.”

※2 This estimate is based on research by Brown University and covers direct and indirect deaths in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen.

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

[6759]MNL168: Best Philippines Online Casino – Secure Login, Register, App Download & Slot Online Link Experience MNL168, the best Philippines online casino! Access secure mnl168 login, quick mnl168 register, and premium mnl168 slot online games. Get the official mnl168 app download and mnl168 casino link to start winning today! visit: mnl168

[8568]JILI178 Login & Register: Best JILI178 Slot & Casino Online in Philippines | App Download Experience the best JILI178 slot and casino online in the Philippines! Secure jili178 login and jili178 register for exclusive bonuses. Get the jili178 app download for 24/7 mobile gaming. Join the top-rated JILI178 casino online today and win big! visit: jili178

[9636]JLLJPH Online Casino Philippines: Login & Register to Play JLLJPH Slot Games. Download the JLLJPH App for the Ultimate Casino Experience. Experience the best of JLLJPH Online Casino Philippines! Use your jlljph login or complete a quick jlljph register to play premium jlljph slot games. Get the jlljph app download for the ultimate mobile gaming experience. Join the #1 jlljph online casino and start winning today! visit: jlljph

[6890]Pokerbet Philippines: Register & Login for Online Slots, App Download, and Exclusive Casino Bonuses. Join Pokerbet Philippines! Secure your Pokerbet login or register to play top Pokerbet online slots. Get the Pokerbet app download & claim your exclusive Pokerbet casino bonus today. visit: Pokerbet

[1770]bmw777 Casino: The Most Legit Online Casino Philippines for the Best Online Slots & Big Wins. Experience the ultimate gaming thrill at bmw777 casino, the most legit online casino PH. Discover the best online slots Philippines has to offer and enjoy massive wins on a secure platform. Join the top-rated online casino Philippines today—secure your bmw777 login and start your winning journey with the best in the business! visit: bmw777

[3748]winjili download|winjili login|winjili slots|winjili register|winjili app Experience top-tier gaming at Winjili, the leading online casino platform in the Philippines. Complete your winjili register today to unlock premium winjili slots and exclusive bonuses. For seamless mobile play, use the winjili download link to get the official winjili app. Secure your winjili login now and start winning with the most trusted name in Filipino online gambling! visit: winjili

[8140]Phlaro Casino & Slots: Official Login, Register, and App Download Philippines Experience the best Phlaro casino games and Phlaro slot action in the Philippines. Use the official Phlaro login or Phlaro register to start playing. Get the Phlaro download app for secure, high-speed mobile gaming and exclusive rewards today! visit: phlaro

[5950]Winph111 Login & Register: The Best Legit Philippines Casino. Experience Top Winph111 Slot Games and Fast Winph111 App Download Today! Winph111 is the top legit Philippines casino! Secure your Winph111 login & register to enjoy premium Winph111 slot games. Fast Winph111 app download available now. visit: winph111

[1930]Jili30: The Philippines’ Best Online Casino for Premium Jili Slot Games visit: jili30

[3874]SSBET77: The #1 Online Casino in Philippines – Fast Login, Register, and App Download for Top Slot Games Experience the #1 online casino in Philippines at SSBET77. Quick ssbet77 login and register process. Get the ssbet77 app download for top ssbet77 slot games and big wins. Join today! visit: ssbet77

[8512]PinasGems Online Casino: Secure Login, Easy Register & Top Slot Games. Download the App Now! Experience the ultimate gaming at PinasGems Online Casino. Enjoy secure PinasGems login, fast PinasGems register, and top PinasGems slot games. Download the PinasGems app now for the best mobile casino experience in the Philippines! visit: pinasgems