The “threat” of foreign interference in elections has become an increasing concern in Japanese media. As grounds for this concern, the media often highlight suspicions that the Russian government interfered in past elections around the world. As an explanation for such interference, they claim it aimed to help certain candidates win and to create “division” in society. Such claims have appeared in cases like the United Kingdom’s 2016 referendum on leaving the European Union (EU), the 2016 U.S. presidential election, and the 2024 Romanian presidential election. Many articles describe Russian influence operations as something that “actually took place,” and in some instances treat the threat of Russian election interference as if it were an established fact.

The problem, as discussed below, is that there is no evidence showing that there were serious attempts to influence these election outcomes—let alone that any such attempts had an actual impact. Of course, that does not mean many countries, including Russia, do not try in some way to meddle in other countries’ elections. That happens frequently around the world. But why do so many Japanese media continue to treat Russian interference in these specific elections as a “given” despite the lack of clear evidence? And what problems arise from overperceiving such threats in this way?

This article first examines the three examples mentioned above individually. It then delves into the broader issues surrounding allegations of foreign interference in elections.

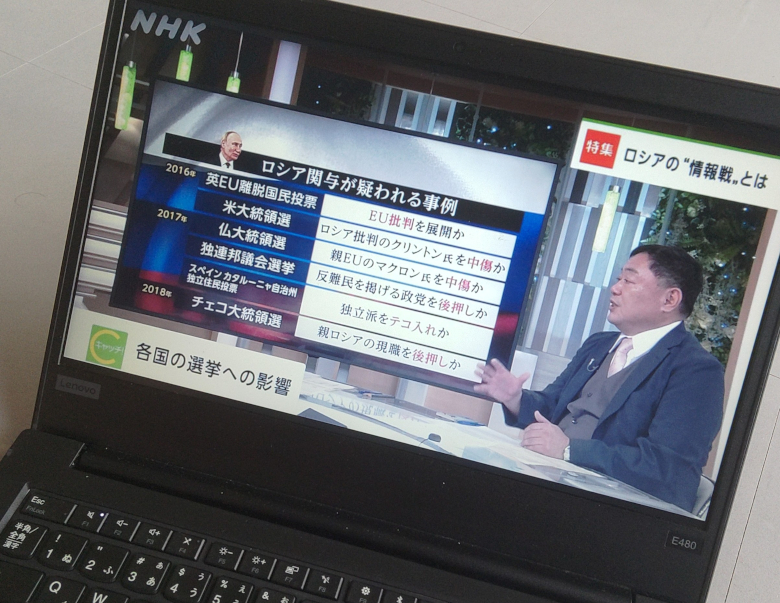

“What is Russia’s ‘information warfare’?”, NHK (broadcast July 22, 2024)

目次

UK withdrawal from the EU (2016)

In June 2016, the UK decided in a referendum to leave the EU, an event that came to be known as “Brexit.” It was only several months later, toward the end of 2016, that voices began to suggest the possibility that Russia may have interfered in some way using social media. These suspicions spread by piggybacking on similar concerns surrounding the U.S. presidential election the same year.

However, evidence of Russian influence operations ultimately failed to materialize. A 2017 study by the Oxford Internet Institute analyzed 22.6 million tweets from Twitter accounts believed to have been created by the “Internet Research Agency (IRA),” which was said to be close to the Russian government, but found that only 416 of those tweets mentioned Brexit between March and July 2016. Another 2017 analysis reported 3,468 Brexit-related tweets from such accounts, but the majority were posted after the referendum. With such small numbers, it is difficult even to infer an intent to influence. A 2020 assessment by the UK Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee also revealed that the government had not identified evidence of Russian influence operations. It did, however, point out that the government had not investigated the matter, and it did not rule out the possibility that attempts at interference may have occurred.

Despite the lack of evidence for attempts to influence, Japanese media still bring up suspicions of such interference and sometimes even present them as if they were established facts. Such claims are also seen via comments made by guest commentators.

On NHK’s “Catch! World Top News,” broadcast on July 22, 2024, the issue of Russia’s “information warfare” was featured, and several cases of alleged Russian meddling in foreign elections were introduced. Regarding the referendum that decided the UK’s exit from the EU, the anchor asked Takahiro Sasaki, an individual “well-versed in information warfare,” “Is it fair to say there was indeed an impact there?” Sasaki responded affirmatively, asserting that “some think tanks” have expressed that view (※1). However, he did not specify which think tanks or which studies he was relying on. Moreover, given that Sasaki is affiliated with the Fujitsu Defense & National Security Research Institute, a company that profits from defense-related contracts, it raises questions about a possible incentive to exaggerate the threat.

Brexit-related demonstration in front of the UK Parliament (2018) (Photo: David Holt / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

A similar line appeared in an Abema Prime program streamed on July 17, 2025. Tomoko Nagasako, a researcher at the Institute of Information Security, listed numerous elections and events in which Russia was said to have intervened. When asked by the anchor whether Russia intervened in Brexit and the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Nagasako replied that it had become “clear” that “Russia’s bot networks were active” and that “the effect of election interference was, in a sense, confirmed.”

Some major newspapers also mention suspicions of Russian interference in the Brexit referendum, while avoiding outright assertions. For example, a May 19, 2018 article in Mainichi Shimbun (※2) stated that “suspicions of interference have surfaced in the UK referendum (June 2016) that decided to leave the European Union (EU).” A June 2, 2025 article in Yomiuri Shimbun (※3) similarly remarked that “Russia and Iran were suspected of interfering” in that referendum.

U.S. presidential election (2016)

Suspicions about Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election have been investigated repeatedly, and the allegations are largely discussed in three categories. First, attempts to influence voters through social media; second, allegations that the Democratic National Committee (DNC) server was hacked and emails were leaked via the whistleblowing site WikiLeaks; and third, the possibility of collusion between Russian government officials and the Donald Trump campaign.

As for attempts to influence voters, while there is somewhat more evidence than in the Brexit case, it was by no means a full-fledged influence operation. Facebook was able to identify only about $100,000 in paid ads by the IRA. A Google investigation found that ad buys from within Russia during the same period totaled about half that amount. In addition, posts on social media by accounts believed to be linked to the Russian government and associated with the election were relatively few, and most were not focused specifically on the election.

A journalist who analyzed Russia-related social media activity surrounding these elections noted that it was “largely irrelevant to the 2016 election, tiny in reach, engagement, and spend, and silly and juvenile in content.” Other analyses also suggest that, judging from the content, it looked more like a marketing campaign aimed at generating revenue than a political effort.

Former headquarters of Russia’s IRA, the hub for social media posts (Photo: Charles Maynes / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Regarding the DNC emails leaked to WikiLeaks, no evidence has emerged that Russia hacked the DNC server. The FBI was not allowed access to the server, and the cybersecurity firm that had access admitted it could not verify whether the server had been hacked or whether staff with access had copied the files. It has also come to light that both the FBI and the National Security Agency (NSA) at the time expressed “low confidence” that Russia hacked the server.

Finally, as for the suspicions of collusion between Russian government officials and the Trump campaign, although there were reportedly some limited contacts between representatives of the two sides, investigations did not find that there was collusion that influenced the 2016 election.

Japanese media have vigorously reported on the possibility of Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Since 2016, the term “Russia-gate” has appeared 481 times in Yomiuri Shimbun, 371 times in Asahi Shimbun, and 305 times in Mainichi Shimbun (※4).

There are also many instances where media outlets do not question or verify the suspicions of Russian interference, instead accepting them at face value. For example, in 2022, an article by an Asahi Shimbun editorial writer (※5) stated without hesitation: “In the 2016 U.S. presidential election, a Russian company posed as U.S. companies and citizens on social media to support Mr. Trump, and the Russian military released information hacked from the opposing camp — the U.S. government said as much in 2019.” (February 21, 2022). Another columnist went even further, declaring, “It is clear there was Russian manipulation that benefited Trump.” (July 19, 2025) (※6).

A research article in Yomiuri Shimbun dated March 14, 2024, citing U.S. government investigations, stated the following about the possibility of Russian influence: “While it is certain that there was interference from Russia in the online sphere, it does not conclude that the impact was sufficient to elect a specific candidate. However, for authoritarian states attempting to interfere, even if they cannot sway the outcome, if they can leave mistrust and confusion around the results, it could be said they achieved considerable success.” Yet, given that full-fledged influence operations have not been confirmed, if “mistrust” and “confusion” were sown, one could argue that the primary cause lies with media that have exaggerated and reported the interference allegations uncritically, and that the impact of any interference itself is comparatively small.

Hillary Clinton speaks at the Democratic National Convention (DNC), United States (2016) (Photo: Maggie Hallahan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Romanian presidential election (2024)

In Romania’s presidential election held in November 2024, relatively unknown candidate Călin Georgescu topped the first round of voting. His political rise has been linked to increased activity on social media such as TikTok. Just two weeks after the election, before the runoff vote, Romania’s Constitutional Court invalidated the entire process, citing irregularities. The government then claimed that Russia had interfered in the election and declassified related documents.

However, those documents did not contain evidence or analytical explanations demonstrating Russian interference. While a campaign that secretly paid influencers through a PR firm was confirmed, that firm was not hired by Russia. In fact, it was later revealed that the National Liberal Party (PNL), a major Romanian political party, funded the campaign. Why they did so remains unclear, but some suspect the PNL calculated that by helping an unfamiliar candidate pass the first round, they would create a more favorable opponent for the runoff.

Japanese media appeared to have little hesitation in reporting suspicions of Russian involvement in this case regardless of the evidentiary basis. The episode seems to fit neatly into an established pattern of coverage about nefarious Russian activities, where mere “suspicions” appear to serve as sufficient grounds to substantiate the possibility of election interference.

In a May 22, 2025 editorial, the Nikkei evaluated the redo election held in 2025, stating that “The Romanian government, reflecting on having allowed what appeared to be Russian election interference, took many steps toward the current runoff.” It further asserted there had been “suspicions of Russian interference” for a “pro-Russian, unknown candidate” in the previous year’s invalidated election. NHK’s program of March 10, 2025 also summarized the situation as follows: Georgescu was “a candidate who surged in the election by using social media and espoused pro-Russian positions,” and the Romanian government “pointed to the possibility that Russia interfered in the election and that forces seeking to spread pro-Russian sentiment were involved in Georgescu’s campaign; the election was invalidated.”

Călin Georgescu, a leading candidate in Romania’s 2024 presidential election (Photo: AUR Alianța pentru Unirea Românilor / Wikimedia Commons [CC0 1.0])

It’s not just Russia

As noted at the outset, a lack of evidence does not necessarily mean there was no interference. It is likely true that Russia has tried to spread information it considers advantageous to itself during the course of foreign elections, especially in Eastern Europe. However, it is problematic to assert full-fledged influence operations—or to imply they were effective—based on mere suspicions without evidence.

It is also noteworthy that when Japanese media focus on foreign election interference, they focus almost exclusively on Russian influence operations. There is some degree of interest in Chinese operations, particularly regarding Taiwan, but they largely neglect influence operations by governments viewed favorably in Japan.

During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union conducted extensive election interference around the world. After the Cold War, numerous instances of intervention by both the U.S. and Russia continued. Interestingly, in July 1996, Time magazine boasted on its cover about U.S. interference in the Russian presidential election won by Boris Yeltsin, reporting “The secret story of how American advisers helped Yeltsin win.”

U.S. interventions have been diverse, including funding and advising opposition groups in Afghanistan and Serbia. Senior U.S. officials have also acknowledged purchasing foreign media outlets to disseminate information and narratives favorable to U.S. interests. Beyond elections, it has been confirmed that the U.S. government has conducted influence operations targeting populations in multiple countries using fake social media accounts and disinformation.

Influence operations targeting foreign elections by other countries have also been reported. While media attention focused on Russia during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the Israeli government also conducted covert influence operations intended to help elect Trump. Moreover, Israel’s broad efforts to influence U.S. politics, including via the powerful lobbying group the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) and other NGOs, cannot be ignored, including influence operations.

Former U.S. Secretary of Defense speaks at the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) (2023) (Photo: U.S. Secretary of Defense / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

While the Israeli government has engaged in large-scale online influence operations, many private Israeli firms are also involved in such work, and it is seen as a “growth industry” in the country. In 2023, a multi-outlet investigation revealed that a group in Israel used more than 30,000 social media accounts to try to influence foreign elections and had the capacity to hack the accounts of particular politicians.

The UK has also been involved in influence operations. In a case revealed in 2025, the British government had contracted with a media agency to pay local online influencers to produce content targeting voters in 22 countries in Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe.

However, influence operations by the U.S., Israel, and the UK are almost never covered by Japanese media, let alone treated as problematic.

Do influence operations actually work?

Even if we assume that many foreign states are conducting full-fledged influence operations, questions remain about their effectiveness—namely, how much they can actually affect the target country.

A sober analysis of the facts suggests the potential to exert real influence is very limited. Today’s online environment is saturated with messaging and propaganda from a diverse array of viewpoints and innumerable sources. In such a context, even if a foreign actor could covertly mobilize large numbers of fake accounts or bots, it is highly questionable whether they could realistically swing the outcome of a national election or meaningfully cause “social division.”

Person looking at a smartphone on a train (2p2play / Shutterstock.com)

Persuading the general public is far from easy. People are exposed daily to a massive volume of advertising and PR campaigns backed by vast sums of money and research. In elections in particular, foreign influence operations must compete with local political organizations, businesses, and other domestic forces. Compared with foreign actors, local forces have far more resources—funds, time, political expression, and local knowledge—to persuade voters. Even if a foreign actor had a method to persuade many people about candidates or issues, in most cases domestic forces would have greater incentives and capacity to conduct such efforts more broadly and effectively than any foreign actor.

Research has found no evidence that voters were influenced by what is described as Russian information operations during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. In fact, other studies suggest that even domestic political campaigns and political advertising have little effect on changing people’s political behavior. Furthermore, research on social media’s influence has found scant evidence that exposure to different content changes people’s political attitudes or participation. In reality, people tend to hold relatively fixed views on political issues. Thus, when someone shares a Russian news article or reposts its claims, it is more likely they already agreed with the message than that they were persuaded by the information.

Russia and other countries may attempt large-scale political influence operations in the future. But given the limited returns to be gained, such a development may not necessarily be likely.

Origins of the focus on Russia

So where did concerns about Russian “influence operations” come from, and why have they become such a major preoccupation for Japanese media?

Suspicions about Russian meddling first emerged during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, surrounding the leaked emails of candidate Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party. The Clinton camp gradually leveraged (and in part constructed) suspicions suggesting ties between Russia and Trump, using them to attack the Trump campaign. After losing the election, Clinton blamed Russian interference for her defeat. A nearly two-year investigation into the alleged collusion between Russia and Trump followed, and the allegations dominated the news day after day. At the same time, the British government began to emphasize the Russian threat. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine brought a new phase to concerns about Russian influence operations.

Election monitoring in Romania (2025) (Photo: OSCE Parliamentary Assembly / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Japanese media interest in suspicions of Russian interference followed this longstanding attention from Western governments and media. In 2025, however, suspicions of Russian involvement around Japan’s 2025 House of Councillors election surfaced in some quarters and drew particular attention.

In both Western countries and Japan, the threat of Russian influence operations has increasingly been discussed in militarized, anxiety-inducing terms such as “information warfare” or “cognitive warfare.” The concept is often used vaguely and broadly. Concerns are not limited to clandestine online disinformation but extend even to ordinary news broadcasts originating from Russia. The scope of concern is increasingly ambiguous, and the media’s focus has expanded beyond merely allegations of foreign election interference to encompass information and viewpoints interpreted as “pro-Russian” or “Russia-leaning.”

All governments, of course, try to disseminate messages they believe will benefit them. Thus, distinguishing between information that can be considered objective and propaganda is extremely difficult. Countries constantly use whatever means are available to criticize and expose the weaknesses of perceived enemies and to win over allies.

International coverage by Japanese media can be said to be strongly influenced by “pro-U.S.” or “U.S.-leaning” perspectives. As a result, the news Japanese media convey includes propaganda and disinformation the U.S. government disseminates to advance its interests. This is due to the fact that perspectives from countries with significant influence in the information environment are necessarily more readily accepted, and because of the central position the United States holds in Japan’s foreign policy and media. Such a biased reporting posture is likely treated as normal and unproblematic because the U.S. is considered an ally.

X (formerly Twitter) headquarters, United States (Photo: 9yz / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Conclusion

As we have seen, discussions in Japanese media regarding alleged Russian influence operations appear to be marked by alarmism and exaggeration. An article in the online outlet President even claimed in its headline that “Russia’s information operations are dominating Japan’s social media…”

For governments, exaggerating fears of foreign interference in the online environment can help justify measures that restrict people’s legitimate access to information and freedom of expression, especially information and speech critical of those in power. The media also have a tendency to align themselves with government movements. Additionally, fear of clandestine malicious actions by hostile foreign forces may help boost media readership and viewership. Moreover, the anti-disinformation industry comprising tech companies and research institutions is expanding, and the companies and organizations involved stand to benefit when governments implement questionable measures against alleged foreign interference.

It is common to scapegoat domestic problems onto hostile foreign forces (and foreigners in general). As a columnist in the UK’s Guardian pointed out, “From Brexit to Donald Trump, it’s easier to pin blame for political outcomes we don’t like on the malevolent hand of Putin than to look hard at our own broken democracies.”

In Japan as well, rather than overreacting to unproven meddling by foreign powers, it may be necessary first to focus on improving digital literacy among citizens and to re-examine the state of domestic democracy.

※1 Sasaki’s response: “Some think tanks have published analyses. After all, the UK wants to turn inward domestically. It seeks to avert attention from the EU imposing united sanctions on Russia, and so on. On the issue of the UK leaving the EU, they spread information that would be advantageous to that outcome. In that context, the Brexit event occurred — that is my analysis.”

※2 Mainichi Shimbun, “Verification: Measures against fake news — EU’s ‘fake’ designation sparks controversy: ‘Interference with reporting’ vs. ‘Measures against information manipulation’” (May 19, 2018)

※3 Yomiuri Shimbun, “[SNS and elections] Politics today (Part 3): Intervention from abroad — a looming crisis” (June 2, 2025)

※4 Based on searches using Asahi Shimbun’s online database “Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search,” Mainichi Shimbun’s online database “Maisaku,” and Yomiuri Shimbun’s online database “Yomidas.”

※5 Asahi Shimbun, “(Reporter’s analysis) Countermeasures against information manipulation: National regulation, education, and the maturity of society are also key — by Editorial Writer Naoo Fujita” (February 21, 2022)

※6 Asahi Shimbun, “(Naoya Fujita’s Net Field Notes) Information that stokes xenophobia, resonant emotions” (July 19, 2025)

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

[5275]Paldobet Login & Register: Best Online Slots and Casino in the Philippines. Download the Paldobet App for Quick Casino Login and Big Wins! Experience the best online slots and casino in the Philippines at Paldobet! Secure your Paldobet login or complete your Paldobet register today. Get the Paldobet app download for a seamless Paldobet casino login experience and start winning big with Paldobet online slots! visit: paldobet

[3430]ph367 Online Casino: The Best Online Gambling Site in the Philippines for Slot Games and Easy GCash Registration. Experience ph367 online casino, the best online gambling site in the Philippines. Play top ph367 slot games with easy ph367 gcash registration and secure ph367 login philippines access. Join now for the ultimate gaming experience and big wins! visit: ph367

[1895]Phlbest Official: Login, Register, and App Download for the Best Online Slots in the Philippines. Get the Phlbest Casino APK Today! Join Phlbest Official for the premier online slots experience in the Philippines! Access easy phlbest login, phlbest register, and phlbest app download options. Get the official phlbest casino apk today and start winning big! visit: phlbest

[8351]PH78 Login & Register: Top Philippines Casino Online, Slots & App Download Join PH78, the top Philippines casino online! Experience seamless ph78 login and ph78 register to access premium ph78 slot games and exclusive bonuses. Secure your ph78 app download today for the best mobile gaming experience and start winning anytime, anywhere! visit: ph78

[7437]The Best Online Casino in the Philippines: Bet777 App Download, GCash Slots, and Fast Payouts. visit: bet777app

[7271]The Best Legit Online Casino in the Philippines for Slots and Fast GCash Payments visit: a45com

[8058]phlago app|phlago giris|phlago register|phlago login|phlago slots Experience premier online gaming with Phlago, the top choice for casino enthusiasts in the Philippines. Download the Phlago app to enjoy a wide variety of Phlago slots anytime, anywhere. Complete your Phlago register today for secure Phlago login and Phlago giris access to start winning big! visit: phlago

[714]3jl Philippines: Best Online Slot & Casino APK – Easy 3jl Login, Register, and App Download Experience the best 3jl online slot and casino games in the Philippines. Enjoy a seamless 3jl login, fast 3jl register, and official 3jl app download. Get the 3jl casino apk today! visit: 3jl

[7780]SuperJili Online Casino Philippines: Easy Login, Register & App Download for Top Slot Games Join SuperJili Online Casino Philippines for the ultimate gaming experience! Enjoy a seamless SuperJili login and register process. Get the SuperJili app download now to play top SuperJili slot games and win big today! visit: superjili

[1591]iq777 Login & Register: Best Philippines Slot, App Download & Link Alternatif Join iq777, the best Philippines slot destination! Experience secure iq777 login, fast iq777 register, and easy iq777 app download. Get the latest iq777 link alternatif here. visit: iq777