Armed conflicts are unfolding across the world. In just the past five years, phenomena that can be called armed conflicts have been reported in at least 50 countries. But how much of the current state of these conflicts and the related issues can we see from information put out by Japanese news organizations? GNV has analyzed conflict-related reporting in Japan for about a decade, revealing many biases present there. This article looks back on eight years of that analysis.

War journalist (Photo: ChameleonsEye / Shutterstock.com)

目次

Conflicts that go unnoticed

The first thing that stands out from analyses of conflict reporting is that most of the world’s conflicts are not covered. One or two conflicts receive concentrated attention, while reporting on other conflicts is minimal. Conflicts that draw attention are not necessarily “chosen” based on scale. Even conflicts with high numbers of casualties and displaced people and extremely severe humanitarian situations often receive little coverage.

For example, the conflict in Sudan that has continued since 2023 has left25 million people—about half the population—in need of humanitarian assistance, and it has been called thelargest humanitarian crisis on record since record-keeping began. Yet despite the scale of the problem, coverage has been very limited, and in 2024 it was reported only a handful of times by major newspapers. In the Asahi Shimbun, for instance, this conflict was covered in roughly one-fortieth as many articles as the Russia–Ukraine conflict and about one-ninetieth as many as the Israel–Palestine conflict.

“Top 10 Hidden Global Stories of 2024” December 19, 2024

The conflicts facing the Democratic Republic of the Congo can also be cited.

The reality confronting the Democratic Republic of the Congo is severe. Conflicts in this country have claimed the highest number of lives in the world since the Korean War of the 1950s, with more than5.4 million deaths between 1998 and 2007 (no survey of deaths has been conducted since 2007). Until 2003 it escalated into a large-scale conflict involving eight neighboring countries, and since then multiple conflicts have continued, including in North and South Kivu in the east and in Kasai in the center.

“The problem is immense, the coverage is scant: Democratic Republic of the Congo” February 21, 2019

The Yemen conflict has also drawn in many neighboring countries and was at one point called the worst humanitarian crisis in the world. Yet it did not receive much attention in coverage.

“Yemen’s humanitarian crisis: Behind an unreported conflict” April 26, 2018

Large-scale conflicts such as those in Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Yemen can be described as “stealth conflicts.”

“Stealth conflicts” are conflicts that are not made visible through reporting and the like. Like stealth bombers that are hard to detect by radar, stealth conflicts are scarcely detected by the news media’s “radar” and thus do not rise to public awareness. The term “forgotten conflicts” also exists, but that refers to conflicts that briefly drew attention before dropping off the media’s radar. Many stealth conflicts never drew media attention to begin with—in other words, they are not forgotten because they were never remembered.

“Determinants of conflict reporting” April 18, 2024

Conflicts that receive attention

Since 2022, the conflicts that have attracted overwhelming attention in coverage are not these countries, but rather the Russia–Ukraine conflict and the Israel–Palestine conflict.

“Conflicts and displaced people not on TV” June 6, 2024

It can be said that conflicts occurring in Europe, and conflicts in the Middle East in which the U.S. military participates, tend to receive particular attention.

The disparity in coverage is not limited to Ukraine. Other European conflicts such as the Bosnian War and the Kosovo conflict in the 1990s were reported more from a humanitarian perspective than African conflicts that were far larger in scale. And the disparity is not confined to conflict reporting. Although Europe accounts for only a few percent of the global totals in terms of the number of refugees and the number of victims of terrorism, past GNV articles haveshown that in bothrefugees andterrorism, coverage linking these issues to Europe makes up more than half of the whole.

“Questioning Japan’s humanitarian reporting through the lens of armed conflict” March 31, 2022

When deciding whether to report on a conflict, the degree of humanitarian harm is not only not prioritized—it may not even be a factor. What becomes important here is balance.

Not every conflict needs to be covered equally. But surveying current conflict coverage, the disparity is far too great. For example, in the Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun, the Russia–Ukraine war accounted forabout 95% of all conflict reporting in the first half of 2022.

“Determinants of conflict reporting” April 18, 2024

So what, in fact, determines conflict reporting?

How much coverage an armed conflict receives is the result of a complex interplay of various factors. In the 2008 book by the author of this article, titledStealth Conflicts: How the World’s Worst Violence Is Ignored, six factors are cited that influence the amount of coverage: 1) national interest/political concern, 2) distance/access, 3) relatability, 4) sympathy, 5) simplicity, and 6) sensationalism.

“Determinants of conflict reporting” April 18, 2024

Children standing in a classroom destroyed by the Yemen conflict, 2018 (Photo: anasalhajj / Shutterstock.com)

The nature of conflict

How do the media capture the realities of a conflict when reporting on armed conflict? Sometimes they simplify conflicts to make them easier for readers and viewers to understand. But this approach often risks causing misunderstandings. The label “civil war” is one such example.

When armed conflicts are reported, aren’t they usually divided into a binary of “interstate war” and “civil war”? In other words, the “state” becomes the primary unit when applying labels to conflict. Among these, “interstate war” tends to be used only in very limited situations. For example, aside from wars in which the national militaries of two or more states clash on a large scale—such as the Gulf War, the Iraq War, and the war in Afghanistan—most cases are labeled as “civil war.” However, once a conflict is labeled a “civil war,” people may mistakenly assume that the conflict is occurring only within one country and that the actors are limited to those within that country.

Looking accurately at the current realities and mechanisms of conflict, it becomes clear that the “state” is not necessarily the appropriate unit. Even if the violence itself occurs within the territory of a single country, almost without exception foreign militaries and armed groups, as well asprivate military companies, are directly involved. It is alsocommon for many foreign companies and other actors to provide bases, funds, supplies, and weapons to conflict parties, or to purchase resources that serve as those parties’ sources of funding. Furthermore, it is extremely common for refugees to flow into neighboring countries and for the conflict itself to destabilize other countries. Cases in which distinct conflicts in the territories of multiple countries blend together are byno means rare. Globalization is further accelerating these phenomena.

“Five misleading words in international reporting (Part 1)” February 27, 2020

Supplementary note: “Do civil wars exist? (GNV Podcast 26)” December 16, 2019

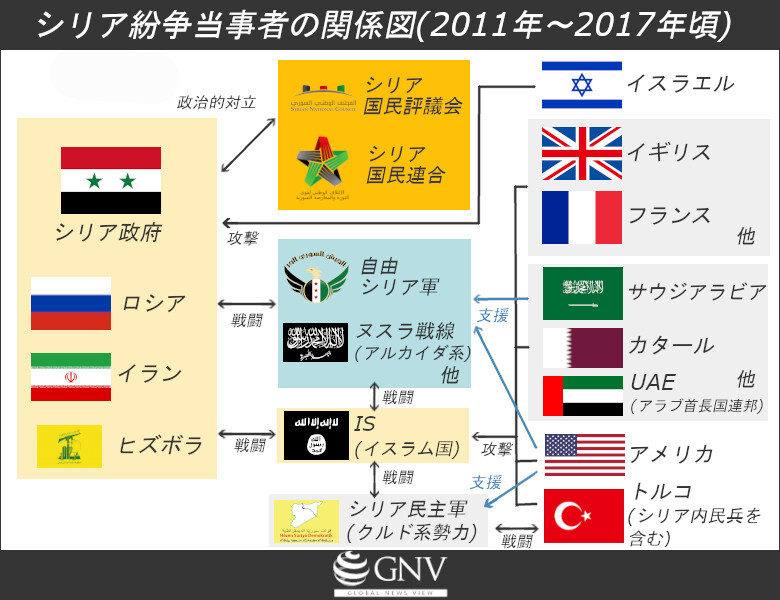

In fact, many conflicts reported as “civil wars” involve multiple actors from outside the country. The Syrian conflict is a prime example.

“Syria: A growing humanitarian crisis” February 16, 2023

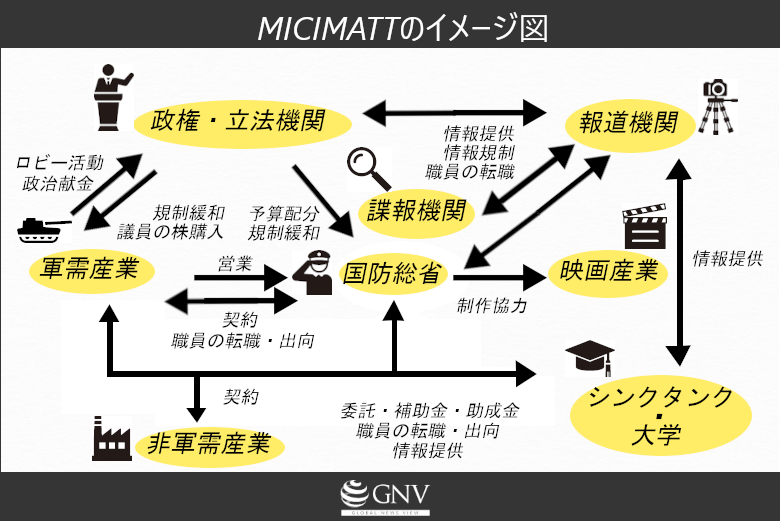

Furthermore, we must also keep in view the ever-expanding arms industry around the world as a factor that enables conflict. In particular, the close relationships among governments, militaries, the arms industry, and other institutions that shape arms production and trade—the so-called “military–industrial complex”—and its expanded form, the “military–industrial–congressional–intelligence–media–academia–think tank complex” (MICIMATT) are crucial.

It must be said that Japanese news organizations have tended to downplay the problems brought about by the military–industrial complex. From reporting, it is difficult to derive answers to questions such as why defense spending is ballooning around the world, why interstate tensions are deepening, and why armed conflicts are becoming prolonged. The enormous military–industrial complexes lurking within countries offer one clue.

“The military–industrial complex: a colossal force unseen in coverage” November 30, 2023

“The military–industrial complex: a colossal force unseen in coverage” November 30, 2023

Peace

Lastly, peace. Even when the media pay attention to conflicts, they rarely report on peace, or on movements and appeals toward peace. For example, in Japanese coverage of the Russia–Ukraine conflict, the paucity of reporting that captures moves toward peace stands out.

“Peace coverage in the Ukraine–Russia war” June 8, 2023

What problems lurk in conflict reporting that centers on combat?

Columns of tanks raising dust as they move along a gravel road; explosions in city streets; children whose tears have run dry. These are scenes you have probably seen at least once in news reports on armed conflict. Such images may feel as though they are vividly conveying the situation on the ground in real time. However, how much of the actual state of the conflict do they convey? Coverage that relies on such imagery may leave us thinking we understand a conflict’s “tension,” “intensity,” and “misery.” But it is likely difficult to grasp the whole picture of a conflict, including its background and efforts toward peace.

What is conflict reporting for? Media outlets and journalists alike are called upon to reaffirm the significance of conveying information about conflicts and to approach conflict reporting accordingly.

“Questioning Japan’s conflict reporting” February 3, 2022

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

0 Comments