In the Central African Republic, located in the heart of the African continent, a conflict has intensified once again. The conflict, which seemed to have calmed around 2014, prompted the United Nations to release a report on May 30, 2017. It stated that acts of violence were surging in the country, with hundreds killed in May alone. As of May 2017, the Central African Republic had produced a cumulative total of about 480,000 refugees and about 500,000 internally displaced persons. The report described rampant heinous crimes, including rape, murder, torture, abductions, and the recruitment of child soldiers. What exactly is the conflict unfolding in the Central African Republic?

Refugees fleeing their homes [CC BY-NC 2.0] Photo: UNHCR/ B. Heger/Flickr

Background of the conflict and the parties involved

Surrounded by Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, and Cameroon, the Central African Republic gained independence from France in 1960, bringing an end to decades of colonial rule. However, even after independence, the country has remained susceptible to intervention by foreign powers, notably France. In 1965, Bokassa seized power in a coup and declared an empire in 1976, proclaiming himself emperor. In 1979, when student protests erupted in the capital, Bangui, Bokassa suppressed them with help from Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), but the crackdown left as many as 400 dead, drawing criticism at home and abroad. As a result, in September of that year, Bokassa was ousted in a coup supported by France, and the empire collapsed. Yet even after a return to a republican system, there were several coups and attempted coups suspected of foreign involvement. This landlocked country of about 4.9 million people has scarcely known “stability.”

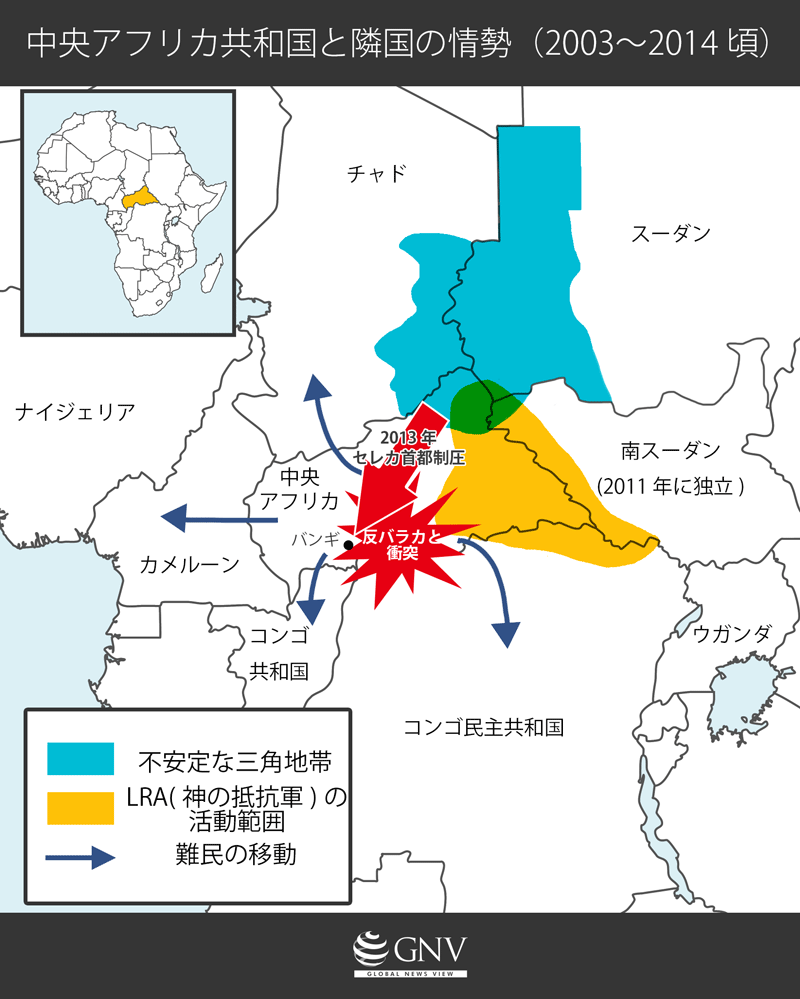

Many countries in Central Africa are also unstable, and because the Central African Republic borders six nations, it inevitably both influences and is influenced by them. In particular, the regions near the borders with Chad and Sudan are known as the “Triangle of Instability.” Understanding the CAR’s conflict is inseparable from these neighboring states. In Sudan, the Darfur conflict intensified around 2003, producing large numbers of refugees and armed groups. Around the same time, the Darfur conflict helped fuel many rebellions in parts of Chad. In this context, multiple armed groups and refugees moved back and forth across the borders with Sudan and Chad. Historically, residents of northeastern CAR share many linguistic, cultural, and religious commonalities with people in western Sudan and southern Chad, making these borderlands closely connected. The conflicts themselves also became tightly intertwined and came to be known not as three separate wars but as a single “conflict complex.”

BBC and Relief Web data used to create this graphic

In March 2003, François Bozizé, a southerner and former army chief of staff, overthrew the previous government with help from Chadian President Déby and assumed the presidency, but his regime, which lasted until 2013, eventually collapsed. Since independence, people from the south have often held power in the CAR, but the coalition that toppled the Bozizé government came from the northeast. Calling themselves “Seleka” (meaning “alliance”), they gained strength by partnering with armed groups from Chad, Sudan, or the border areas. However, even after taking power, Seleka attacks continued, prompting the formation of an armed group called “anti-Balaka.” The backlash did not remain limited to fighting Seleka. Since Seleka was largely composed of Muslims from the north, and anti-Balaka drew many Christians, anti-Balaka forces carried out retaliatory attacks on Muslim civilians. Vast numbers of Muslims became refugees and fled to neighboring Cameroon and Chad or were internally displaced—numbering around 800,000. It was a vicious cycle of violence and reprisal that engulfed civilians, including women and children.

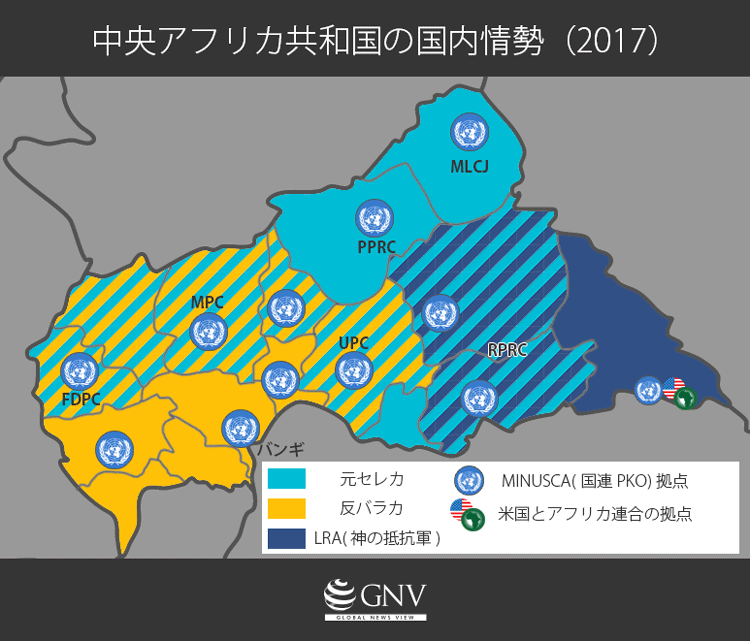

Amid this situation, Michel Djotodia, a Seleka figure who succeeded Bozizé as president, failed to rein in the armed groups. His ability to govern came into question, and after losing the support of Chad, which had backed CAR since the Bozizé era, he resigned. With additional intervention by France, regional bodies, and the African Union, Seleka was effectively dissolved in 2014. Anti-Balaka, emboldened, stepped up attacks on Muslims, and former Seleka elements were pushed out of the capital, Bangui, bringing a tentative lull to the CAR. Following elections, President Faustin-Archange Touadéra took office in March 2016, but his administration has effectively exercised control only in Bangui—and even there, only to a limited extent.

A rebel fighter in northern CAR [CC BY-SA 2.0] Photo: hdptcar/flickr

Today, in other regions where effective governance is lacking, the cohesion of Seleka—originally an amalgam of separate armed factions—has loosened, and the various groups have dispersed across the country. Six main ex-Seleka armed groups (Note 1) are consolidating and seeking to expand their control to pursue their own interests. Further aggravating the turmoil in the CAR is the group known as the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Formed in 1987 as an anti-government force in Uganda, the LRA is notorious for atrocities, abductions, and the use of child soldiers. In recent years, to evade the Ugandan government, it has crossed borders and operated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Central African Republic, and Sudan, becoming a transnational armed group. In the CAR, where power vacuums have persisted for years, even when the situation appears calm, armed groups can operate with relative ease, and rebellions can break out readily. In that sense, the CAR has been a convenient place for the LRA to take refuge.

International efforts

Although multiple factors have intertwined to complicate the situation in the CAR, it is not the case that the world has taken no action. In 2013, through the mediation of the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the government, Seleka, and others concluded a peace agreement, albeit temporarily. As conditions later deteriorated, the UN Security Council authorized the deployment of the African-led International Support Mission to the Central African Republic (MISCA) and French forces. Currently, the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) is active. Under MINUSCA’s program, a total of about 12,870 military and police personnel have been deployed. However, this number is vastly insufficient relative to the scale of the challenges and the mandate, making operations difficult. In addition, to eliminate the LRA, the United States, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan, the Central African Republic, and others have deployed troops, but the United States and Uganda—key players—have announced their withdrawal, leaving the outlook uncertain.

Based on data from the CRS Report and the United Nations

What underlies the conflict and the responses

Because many Muslims joined Seleka and many Christians joined anti-Balaka, the religious divide is often emphasized in this conflict. In reality, however, the fault lines are not only religious. They also include a power-distribution divide between the south, which has historically held power, and the north, which has not, as well as divisions among multiple ethnic and linguistic groups. Underpinning these is also a struggle over wealth generated by natural resources.

The various countries involved in the CAR likely have their own interests to protect. The CAR is rich not only in gold and diamonds but also in uranium and timber, and oil exploration is underway. Thus, some see foreign aims as focused on natural resources. Former colonial ruler France is the CAR’s largest trading partner and is developing uranium mines. France has assisted CAR governments in many ways, reminiscent of the colonial legacy, but it did not help Bozizé when Seleka overthrew him in 2013. As Bozizé himself stated, that was because he had sold oil extraction rights not to France but to China. In South Africa, which deployed troops in 2013, relatives of the president and party affiliates were involved in resource businesses in the CAR—oil, uranium, diamonds—leading to claims that the state intervened militarily to protect personal interests.

A truck transporting timber in the Central African Republic [CC BY 2.0] Photo: WRI Staff

Not a “civil war”

The conflict unfolding in the CAR is not merely a “civil war” driven by religious or ethnic antagonism. It is rooted in a broader context that integrates multiple armed conflicts in Central Africa and has long been open to foreign intervention. Beneath it lie cross-border issues intricately intertwined: regional power struggles and contests over political power and natural resources. Forces that fight together one day may split the next. The blurred lines between armed groups further fuel national disorder. If foreign powers that intervene in the name of restoring security also harbor ulterior motives to advance their own interests, what path can the CAR take? One cannot understand this conflict without considering it from multiple perspectives.

People seeking shelter in a church [CC BY 2.0] Photo: UNHCR/ B. Heger/flickr

Note 1: The main ex-Seleka armed groups are FDPC (Central African Democratic Front), FPRC (Popular Front for the Renaissance of the Central African Republic), MLCJ (Movement of Central African Liberators for Justice), MPC (Patriotic Movement for the Central African Republic), RPRC (Patriotic Rally for the Renewal of the Central African Republic), and UPC (Union for Peace in the Central African Republic).

Writer: Madoka Konishi

Graphics: Mai Ishikawa

普段生活していたら、この様な情報は分からないですが世界を知ることがとても大切だと感じました。これからもっとアフリカの情報を知りたいと思います。

ボカサの孫とか今どうしてるんだろう?

グーグルアースで多分唯一一切360oカメラの無い国なんですよね。ここ。治安情報もレベル4(最大)でアフリカの中でもトップクラスだし……