In 2017, in the month of July, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was adopted at the UN General Assembly with the support of 122 countries. Nuclear weapons are sometimes called “indiscriminate weapons of mass killing” and can kill hundreds of thousands of people with a single detonation. The treaty comprehensively and without exception bans the development, possession, and use of nuclear weapons, going a step further than previous treaties that merely limited them. In 2022 in June, the first Meeting of States Parties to the treaty was held. Not only did 49 States Parties attend, but 34 non-parties also participated as observers. However, many nuclear-armed states such as the United States and Russia, as well as many countries under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, have participated in neither the treaty nor this meeting.

One region actively engaging with the treaty is the Pacific Island countries. Of the 14 Pacific nations, 10 have ratified or acceded to the treaty, including Fiji, Kiribati, Palau, and Samoa. Other countries that have not ratified the treaty nevertheless participated in the Meeting of States Parties as observers. Why is there such vigorous involvement with this treaty in the Pacific? The background lies in the history of large-scale nuclear testing conducted in this region.

This article outlines nuclear testing overall, details of tests carried out in the Pacific Island countries, the harm that continues to this day, and the responses to it.

Nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands (Photo: International campaign to abolish nuclear weapons / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

目次

Overview of nuclear testing

Nuclear weapons were first built in 1945 during World War II. The Allied powers, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada, mobilized scientists to develop and produce them to counter Axis powers such as Germany, Italy, and Japan. Nuclear weapons are devices that utilize nuclear fission, which occurs when neutrons strike elements such as uranium. The energy released by fission reaches tens of millions of degrees, and the destructive force extends over a range with a diameter of several kilometers, making them orders of magnitude more powerful than conventional explosives. In fact, when a nuclear bomb was dropped on Hiroshima in Japan in 1945, damage spread across a 6-kilometer diameter area and approximately 140,000 people were killed; in Nagasaki, the damage extended across a 7-kilometer diameter area and approximately 70,000 people were killed.

Because nuclear fission requires advanced scientific and technological capabilities, conducting nuclear tests is necessary to investigate the functions and effects of newly developed nuclear weapons. Nuclear tests can be broadly classified into four types: atmospheric tests, exoatmospheric (outer space) tests, underwater tests, and underground tests. Atmospheric tests include those conducted on the ground or dropped from aircraft. They loft soil and dust into the air upon detonation, producing large amounts of radioactive fallout such as ash. Exoatmospheric tests are conducted using rockets, with objectives that include evaluating the destruction of enemy satellites. They generate large amounts of space debris, and the electromagnetic pulse generated by the explosion affects electronic equipment on the ground. Underwater tests are conducted by methods such as suspending a nuclear bomb underwater from a vessel and detonating it. Radioactive water spreads and contaminates surrounding areas. Underground tests, if fully contained, do not produce fallout, but subsidence can occur afterward, and if the explosion vents to the surface it can release large quantities of radioactive material.

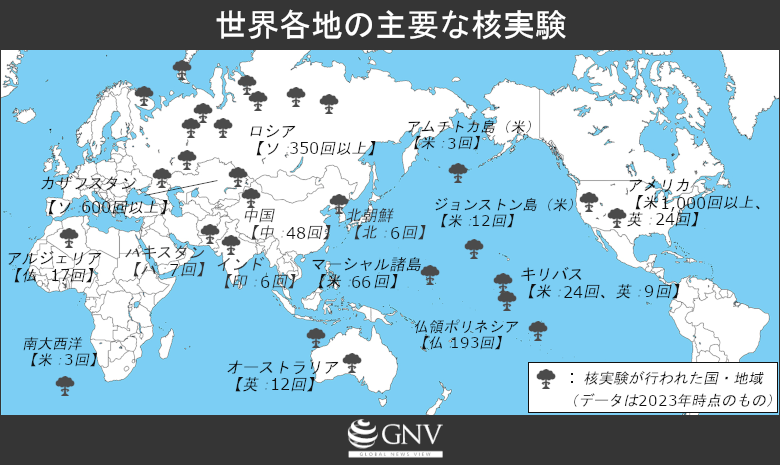

Next, we look at the history of nuclear testing by country. The United States conducted 1,030 nuclear tests between 1945 and 1992. In July 1945, it carried out the world’s first nuclear test, the Trinity test, in New Mexico, and went on to conduct tests in other U.S. states as well as in the Marshall Islands and Kiribati in the Pacific. The Soviet Union conducted 715 tests between 1949 and 1990 . It conducted many of these at the Semipalatinsk Test Site in Kazakhstan and also carried out tests sporadically across Russia. France conducted 210 tests between 1960 and 1996. It initially conducted tests in its then-colony Algeria, but moved its testing ground to French Polynesia after Algeria gained independence. The United Kingdom conducted a total of 45 tests, mainly in Australia and Kiribati. China conducted 45 tests, primarily in the northwest of the country. North Korea carried out a total of 6 tests, all since the 2000s. India conducted 3 tests, and Pakistan conducted 2. South Africa, which abandoned its nuclear weapons program, and Israel, which is believed to possess nuclear weapons, are also thought to have conducted nuclear tests in the past, though this is not certain.

We next examine efforts to restrict testing. In 1963, the Partial Test Ban Treaty was concluded among countries including the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom, banning all nuclear tests except those conducted underground. France and China did not join this treaty. Its stated purpose was to prohibit nuclear testing in the atmosphere and underwater in order to prevent environmental contamination by radiation. However, at the time, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom possessed underground testing capabilities and could continue testing even after the treaty’s conclusion, whereas France and China did not have such technology; there were thus suspicions that the early nuclear powers sought to institutionalize their oligopoly over nuclear weapons. In 1996, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, which also bans underground tests, was adopted by the UN General Assembly, but countries including the United States and China have not ratified it, so it has not entered into force. Moreover, while most countries no longer conduct nuclear tests today, this also reflects the development of technology that allows nuclear testing to be simulated on computers.

As this overview shows, many nuclear tests were conducted in the Pacific Island countries. In fact, from 1946 to the present, the United States, the United Kingdom, and France conducted as many as 315 tests in this region. As noted earlier, colonies of high-income countries—such as the Marshall Islands, French Polynesia, and Kiribati—served as the main testing grounds and suffered tremendous damage as a result. Below, we look in detail at the large-scale U.S. tests in the Marshall Islands and France’s tests in French Polynesia.

Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands comprise more than 1,200 islands. Although originally uninhabited, people began migrating from Micronesia around the 1st century, and from the 18th century people from great powers such as Britain and Germany also settled there. In 1886 it became a German protectorate, and after World War I, from 1920 it became a Japanese mandate. During World War II it was used as fortified military bases, and after the war it came under U.S. administration as a Trust Territory. When it gained independence in 1986, it concluded the Compact of Free Association with the United States. Under this arrangement, the United States provides financial support to the Marshall Islands in exchange for continuing to administer its defense and security.

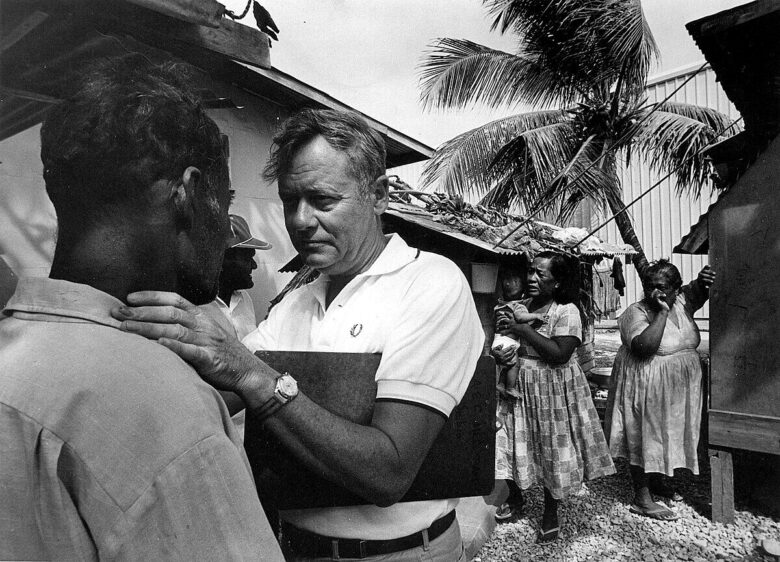

A radiation-exposed person in the Marshall Islands receiving a medical examination (Photo: ENERGY.GOV / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Between 1946 and 1958, the United States conducted 67 nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands. Tests were conducted primarily at the Bikini and Enewetak atolls, including both atmospheric and underwater detonations. The total explosive yield during the testing period reached 108.5 megatons (※1), and radiation fell across more than 2,000 islands and areas within Marshallese territory. The effects of radiation caused health damage across the Marshall Islands, including burns, congenital disorders, and cancers, and the environment was also affected—for example, coral reefs were decimated at the test sites.

During the testing period from 1946 to 1958, residents of Bikini and Enewetak atolls were forcibly relocated to uninhabited islands such as Rongelap Atoll and Kili Island. Regarding Bikini Atoll, in 1968 U.S. authorities declared that radiation levels had sufficiently decreased, and about 100 islanders returned in 1972. However, subsequent surveys revealed high levels of residual radiation, and the islanders were evacuated again in 1978. Bikini islanders still cannot return home. At Enewetak Atoll, decontamination work began in 1977, and in 1980 the western side of the atoll was declared safe and repatriation proceeded, but some areas still remain contaminated.

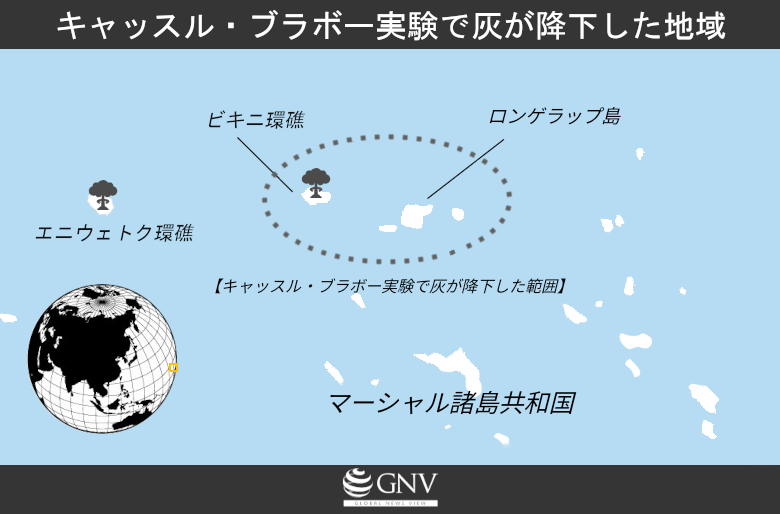

One of the most damaging tests was the Castle Bravo test conducted in 1954, an atmospheric detonation with a yield of 15 megatons. Conducted at Bikini Atoll, this test produced fallout that reached unexpected locations such as Rongelap Island and Utirik Atoll. Although island residents had been informed of the test in advance, they were not evacuated and were therefore exposed. It has been suggested that the United States may have intentionally allowed harm to occur for human experimentation. The Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon No. 5 (Daigo Fukuryu Maru) was also exposed while sailing near Rongelap. Damage to soldiers and U.S. Navy vessels involved in the test was also reported.

Exposed individuals suffered health problems such as itching and vomiting, and many developed cancers such as thyroid cancer decades later. A 2010 investigation by the U.S. National Cancer Institute found that about 55% of cancers occurring on Rongelap Island were attributable to fallout from the Castle Bravo test. Environmentally, coral reefs and the ecosystems they sustained were devastated. It is believed that radioactive contamination remains on Rongelap Island, and residents still cannot return.

In 2017, the Marshall Islands initially voted in favor of adopting the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons at the United Nations, but ratification was not achieved because it was feared in parliament that joining the treaty would violate the Compact of Free Association with the United States. However, at the 2022 Meeting of States Parties, the country participated as an observer to closely follow what victim-assistance measures would be proposed for states affected by nuclear testing.

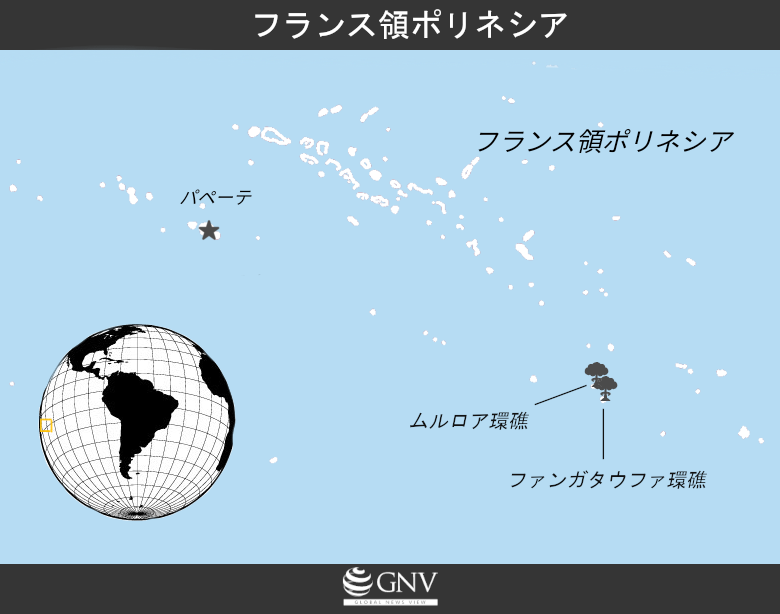

French Polynesia

French Polynesia consists of 118 islands, of which 67 are inhabited and the rest are uninhabited. The region was originally ruled by the Pomare Dynasty centered on the Society Islands, but became a French protectorate in 1844 and was annexed by France in 1881. After World War II, in 1946 it became an overseas territory of France, a local assembly was established, and it was given the right to elect a small number of representatives to the French parliament. Although partial autonomy has expanded since then, it has not achieved full independence.

Between 1966 and 1996, France conducted 193 nuclear tests in French Polynesia. Tests were conducted mainly at the Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls, including both atmospheric and underground detonations. According to IAEA surveys, radioactivity spread not only to the testing grounds of Moruroa and Fangataufa and the Tureia Atoll, where evacuation measures were implemented as a danger zone, but also to islands such as Tahiti, exposing many people. Due to the long duration of the tests, it is estimated that 110,000 people—nearly the entire population of French Polynesia—were exposed. However, France is said to have concealed radiation levels. A joint investigation by the UK firm Interprt and Princeton University found that dose estimates for residents presented by French authorities in 2006 were between one-half and one-tenth of the actual results. The environmental impact has also been enormous: Moruroa Atoll has repeatedly experienced cracking, subsidence, and landslides, and there is a possibility of large-scale collapse across the atoll in the long term.

Opposing these French nuclear tests, the international environmental NGO Greenpeace sailed vessels near Moruroa Atoll to stage protests. In 1985, however, the group’s ship, the Rainbow Warrior, was bombed by French agents in the port of Auckland, New Zealand, killing 1 person. The ship had planned to depart Auckland for Moruroa Atoll to conduct protest activities. French authorities initially denied involvement, but later that year a British newspaper revealed that President François Mitterrand had approved the operation, forcing several top-level members of the Mitterrand cabinet to resign. Of the agents who carried out the operation, 2 were sentenced by a New Zealand court to 10 years’ imprisonment for charges including manslaughter, but were released after 1 year following negotiations by the French government.

Insufficient compensation and moves toward denuclearization

The harm from nuclear testing described above is not merely temporary; it continues over the long term. It is known that radiation exposure increases survivors’ subsequent risk of developing cancer over time. In the Marshall Islands, an estimated 170 cases of cancer attributable to exposure occurred among residents alive between 1948 and 1970. A survey from 1986 to 1994 found that in irradiated areas of the Marshall Islands, the risk of liver cancer was 15 times higher for men and 40 times higher for women compared to the U.S. average. Despite such long-term harm, compensation has been inadequate. Under the 1986 Compact of Free Association, the United States decided to pay $150 million in compensation to the Marshall Islands, but this has been criticized as insufficient, especially given cancers that will continue to occur.

France has compensated only 63 civilians exposed in French Polynesia. In the background is the fact that France’s compensation commission for nuclear test victims has refused to recognize causality between radioactive substances from the tests and victims’ cancers. Not only has compensation been inadequate, but French authorities have not even apologized to the victims of nuclear testing.

Nuclear testing in French Polynesia (Photo: Pierre J. / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

In the Pacific Island countries used as testing grounds, there have also been positive moves toward denuclearization. First is the Treaty of Rarotonga, which entered into force in 1986. It designates the South Pacific as a nuclear-weapon-free zone and comprehensively prohibits the manufacture, acquisition, possession, and testing of nuclear weapons, as well as the dumping of radioactive material into the ocean, within the territories of States Parties. As background, as seen above, numerous nuclear tests were conducted in the region, and there were concerns about marine environmental pollution from the dumping of nuclear waste. All 13 independent states of the South Pacific (※2) have ratified this treaty. Civilian demonstrations were also seen in the region to stop nuclear testing. In 1995, people in the Cook Islands, together with residents of Tahiti, held a protest march calling for an end to the tests and for peace.

The Pacific Island countries also played an important role in the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. They actively issued statements during the treaty’s negotiating conference. Of the 50 ratifications required for the treaty’s entry into force, 10 were by Pacific Island countries.

Conclusion

As we have seen, large-scale nuclear tests in the Pacific Island countries have caused enormous harm to both human health and the environment, and residents continue to suffer from cancers and other consequences to this day. Nevertheless, perpetrator countries such as the United States and France have minimized or concealed the damage and have not provided sufficient compensation. There are even suspicions that harm was intentionally caused for the purpose of human experimentation. Against this negative historical backdrop, the Pacific Island countries have concluded and actively joined treaties banning nuclear weapons.

We will continue to monitor developments to ensure that victims of nuclear testing receive adequate compensation and to watch for the realization of a world free of nuclear weapons.

The Prime Minister of Fiji delivering a speech at the first Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (Photo: UNIS Vienna / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

※1 A unit used mainly to express the yield of nuclear weapons; 1 megaton is one million times a ton. As a reference point, the combined explosive energy of the nuclear weapons dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was 0.037 megatons.

※2 Australia, Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, Western Samoa

Writer: Koki Ueda

Graphics: Ayane Ishida

日本は被爆国ですが、核兵器禁止へ向けて報道されるのは8月6日あたりしか見受けられず、核兵器が国民の関心の外にあるように思います。条約への動きは、核兵器のない世界へ働きかける責任のようにも感じます。

太平洋の人たちを何だと思ってるんでしょう。

核実験した国は誠実に謝るべき。誠実に補償すべき。

広島長崎への原爆投下からもうすぐ80年。今、有事に備えるために、戦力や核兵器が必要という声が強まっています。そのような意見が出てくるのも仕方のないことかもしれませんが、核実験で被害を受けた人々がいるということ、核が人体に及ぼす影響についても知っておく必要があると思いました。

記事を興味深く拝読しました。一部の高所得国が「核兵器には抑止力があるから」という主張を現在強めていますが、そうではないということがこの記事からも伝わってきます。核実験の下で長い間危険にさらされ、命までも落としている人々の存在を忘れずにいるためにも、こういった記事が世に出ることは貴重だと考えます。