For many years, space development was monopolized by great powers. However, advances in science and technology have lowered the barriers to entering space, and the actors involved in space—from small and medium-sized countries and companies to, more recently, individuals—have expanded. Their purposes range widely, including scientific research, military, and commercial uses. Of course, there are many benefits to be gained from space development. Nevertheless, it is also true that behind the positive aspects of space development lie negative impacts.

When you open the Global News View (GNV) homepage, the first thing that catches your eye is an image of Earth photographed from space. For the first time, a GNV article steps off the planet to analyze the problems of space development from multiple perspectives, including militarization, the environment, and equity.

The launch of Space Shuttle Discovery (NASA / Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

目次

History of space development

The confrontation and military competition between the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics during the Cold War are inseparable from the story of space development. That history began in 1957, when the Soviet Union launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1. In 1961, the Soviet Yuri Gagarin became the first human to reach outer space. That same year, 1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy announced the Apollo program, and in 1969 the Apollo 11 mission commander, Neil Armstrong, achieved the first moon landing. With humans reaching outer space, countries recognized the importance of the peaceful use of outer space, and just 2 years after the first satellite launch, in 1959, the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) was established as a forum to discuss the peaceful uses of outer space at the international level. Since then, discussions have continued on the peaceful use of space. However, alongside debates on peaceful use, the aspects of great-power rivalry and competition remained, and the military dimension never disappeared. In this way, outer space initially reflected the U.S.-Soviet Cold War structure and became a stage for the struggle for hegemony between the two superpowers.

Nevertheless, science and technology advanced, and the number of countries venturing into space increased. After the U.S. and the Soviet Union, France succeeded in launching a domestically launched satellite into orbit in 1965. One point worth noting is that France’s initial launch took place not in present-day French territory but at the Amaguir launch site in Algeria, a former colony, Amaguir Launch Facility, which can be seen as securing a site suitable for launches outside the home country through colonialism. Subsequently, Japan (1970), China (1970), the United Kingdom (1971, also launched from Australia, a former colony), and India (1980) succeeded with their own launches. The countries mentioned thus far are so-called high-income countries and the populous giants China and India—ranked first and second by population at the time—illustrating how space remained an oligopoly for a long time.

Increase in actors in space development

In the 21st century, the base of space development has further broadened. As a result of miniaturization and cost reduction of satellites, by December 2022 the number of countries that own satellites under their national name had reached 105 countries; considering that about 20 years earlier, around the turn of the 21st century, the number was 14, the spread has been rapid. One important point: possessing a satellite under one’s national name and having the ability to launch independently—that is, the ability to launch rockets that carry equipment such as satellites—are entirely different issues. Even now, only 11 countries can launch satellites independently. In other words, since 1980, only four countries—Israel (1988), Iran (2009), North Korea (2012), and South Korea (2022)—have been added, so space development can still be considered oligopolistic. Both cost and technological capability heavily influence this.

We discussed the U.S.-Soviet competitive aspect of space development, but with the end of the Cold War this rivalry eased, and the International Space Station (ISS) began operations in 1998. The ISS is a space station where numerous countries, including the United States and Russia, cooperate on space development, conducting daily research and experiments in orbit. To date, 266 astronauts from 20 countries have visited the ISS for research. Although the ISS has developed under U.S.-Russian cooperation, following the Russia–Ukraine conflict, Russia announced in 2022 that from 2024 onward it would withdraw from the ISS and transition to its own space station. However, as a follow-up in 2023, Russia stated it would continue until 2028, with the policy shifting back and forth, raising concerns about the impact on stable space development.

Moreover, the actors are not limited to states and intergovernmental organizations. In recent years, more companies have expanded their businesses into space. Worldwide, the number of space-related companies exceeds 10,000, and in 2021 the market size surpassed $4 trillion. The scale is expected to expand further, with projections that it could exceed $10 trillion by 2030. In addition, personal involvement as tourists through space travel is becoming a reality. Space tourism is expected to increase, and although limited to the wealthy, the number of people involved will likely grow further.

International Space Station (ISS) (NASA Johnson / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Benefits of space development

What benefits has space development brought to humanity, and what benefits could it bring in the future?

First, we can cite the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) (※1), which contributes to life on Earth. GNSS was originally developed for military purposes, but it has now penetrated deeply into everyday life and is widely used in location-based services and navigation services.

Next, satellite broadcasting. The satellite broadcasting of television we commonly use today would not exist without space technology. Satellite broadcasting has the advantage that even where terrestrial broadcasting infrastructure cannot be developed, households can receive broadcasts by installing a small parabolic antenna, making it a very useful means of information especially in low-income countries.

Improved accuracy in weather forecasting is also one of the benefits brought by space development. With advances in satellite technology and supercomputing, the accuracy of a one-day forecast in 1980 is now equivalent to the accuracy of a five-day-ahead forecast today.

Space development is also useful in understanding global environmental problems and finding ways to solve them. Space satellites have played an important role in understanding the causes of global warming by providing massive amounts of data to study variations in Earth’s orbit. They are used to monitor deforestation and collect data on sea-level rise, contributing to the protection of the global environment. In the Amazon rainforest, forest fires are a problem, with as many as 30,000 in a single month; satellites can monitor forest fires and, in some cases, even predict them before ignition.

There have also been medical advances stemming from progress in space development. Remote sensing (※2) technology has been applied to infectious disease epidemiology, helping to understand environmental factors in disease spread and to predict risks. In onboard experiments, analyzing the effects of microgravity on blood circulation has helped elucidate how arteries age and how to prevent certain types of heart failure.

A medical experiment on the ISS by an astronaut from the European Space Agency (ESA) (Samantha Cristoforetti / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

Militarization of space

Thus far we have explained the benefits we can obtain by conducting space development. From here, we focus on the militarization of outer space.

As noted, it is not hard to imagine that the space race, intensified by U.S.-Soviet Cold War rivalry, was related to the military from the outset. Space, the ultimate high ground, has high military value, and controlling outer space is advantageous for national military strategy. What does “military” mean in this context? Is outer space a battlefield like in science fiction movies, with laser beams crisscrossing between spacecraft? Basically, that image is not very accurate. Many objects exist in Earth orbit, and reckless attacks on space assets would greatly affect the overall operation of space; thus, although military support operations and combat scenarios have been considered, outer space long remained a sanctuary in which both the U.S. and the Soviet Union refrained from actual attacks.

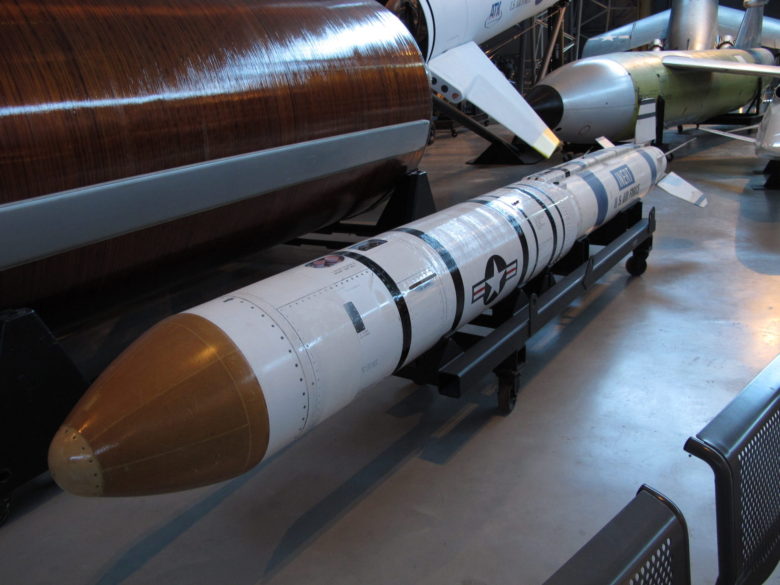

However, militarization has appeared in various forms. For example, anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons that attack satellites in orbit. These technologies existed as early as the late 1950s when space development began, with the United States conducting its first demonstration in 1959 and the Soviet Union in 1968. In 2007, the Chinese military conducted an ASAT test, destroying one of its own satellites. Among other factors, China’s entry into the ASAT field was one trigger for the U.S. Department of Defense in 2018 to officially recognize outer space as a war-fighting domain. Subsequently, in 2019, India conducted its first ASAT test, bringing the total to 4 countries that have developed ASAT weapons.

Intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) are another example of the militarization of space. ICBMs are long-range missiles that traverse continents; they are first launched into outer space and then re-enter the atmosphere to detonate nuclear warheads, etc. The forerunner of militarization in outer space was this ICBM, and the R-7, which launched the world’s first satellite, Sputnik 1, was the world’s first ICBM. After such weapons appeared, full-fledged discussions on the peaceful use of outer space began.

Moreover, militarization is not only about obviously military weapons. For example, satellites are used for reconnaissance of enemy territory and for remote sensing. In addition to physical weapons that destroy satellites, ASAT attacks can also be carried out by jamming communications. Jamming involves emitting noise at the same radio frequency within a satellite antenna’s field of view to disrupt communication between the target satellite and the ground.

An ASAT weapon on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, United States (Kelly Michals / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Legal frameworks against space militarization

Is nothing being done to address such militarization? Of course, that is not the case. After human activity in outer space began and the UN General Assembly adopted the establishment of COPUOS in 1959, the first major outcome came in 1961 with the adoption of the “Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space.” However, since the declaration is not legally binding, COPUOS’s next goal was to draft a treaty that could legally bind states. As a result, in 1966 the “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (commonly, the Outer Space Treaty)” was adopted. This treaty has been joined by 113 countries, including the U.S. and Russia, and is recognized as the “constitution of space.”

The treaty stipulates the peaceful use of outer space, freedom of exploration and use, non-appropriation of outer space, and the principle of attributing responsibility to states. The provisions on peaceful use are particularly relevant to the militarization of outer space. Article 4 (※3) divides space into “outer space” and “celestial bodies,” and stipulates that at least celestial bodies must be used “exclusively for peaceful purposes,” which is considered to have achieved demilitarization of celestial bodies under international law. However, regarding outer space, the treaty only stipulates that nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction should not be placed in Earth orbit, and in principle it does not regulate other military activities.

Therefore, it is difficult to address the militarization of outer space with this treaty alone. Four additional treaties (※4) were adopted after the treaty’s enactment. However, even with these, effective regulations on militarization have not been achieved.

A COPUOS meeting (UNIS Vienna / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Furthermore, no new treaties have been adopted for more than 40 years since the last one. This relates to the consensus method used for adoption in COPUOS, as well as the difficulty of forming a consensus among members after membership increased from 28 countries at the time of the Outer Space Treaty’s adoption to 102 countries. The United States takes a negative stance toward establishing new treaties, while China and Russia have proposed a draft “Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space (PPWT),” which has not been adopted. As a result, although discussions are being held under the topic of “Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS)” in forums including the Conference on Disarmament (CD) and the UN General Assembly First Committee, a prolonged stalemate persists, and no meaningful results have been achieved against the accelerating militarization.

In recent years, however, a noteworthy development occurred at the UN General Assembly. In 2020, the UK led the adoption of a resolution calling on UN member states to reduce space threats through norms, rules, and principles of responsible behaviors, with 150 countries voting in favor. Along with this adoption, a new working group on space security was established, marking a step forward toward creating effective disciplines.

Other instruments, while not directly regulating space weapons, are related to outer space, such as the “Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT)” and the “Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT),” which prohibit nuclear testing in outer space, and the “Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques,” which prohibits the military use of techniques that change the structure, composition, or dynamics of outer space.

Environmental issues caused by space development

So far we have looked at space development from the perspective of militarization, but what other problems exist? Since space development began, a wide range of problems attributable to it have arisen. Here, we address environmental issues.

Scientific and technological development often brings environmental problems—at sea, on land, and in space. The foremost environmental issue in space is space debris. Space debris consists of non-functional satellites, defunct satellites, discarded satellite parts, and other fragments. These can collide with operational satellites and space stations, causing fatal damage. They also arise from the use of ASAT weapons mentioned earlier. Another concern is the Kessler Syndrome—a phenomenon in which increasing space debris collide with each other and fragment into more pieces, causing their numbers to grow exponentially (Kessler Syndrome). Countermeasures are urgent. To address increasing space debris, COPUOS has adopted the “Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines” and the “Guidelines for the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities (LTS Guidelines).”

Remains of a rocket booster found at sea (NASA / Wikimedia Commons [public domain])

There are also warnings that the fuel used to launch satellites and rockets contributes to air pollution, climate change, and depletion of the ozone layer. Until recently, air pollution and climate change attributable to space development had received relatively little attention. This is because rocket launches are not that frequent as events, and the fuel consumed annually by the space industry is about 1% of what aviation consumes, leading many to view it as a low priority. Conversely, however, given how frequent aviation is compared to relatively infrequent rocket launches, the fact that fuel consumption from launches amounts to one-hundredth that of aviation suggests that the fuel consumed per rocket is enormous.

Studies also show that the black carbon emitted by rockets in the upper atmosphere—where airplanes do not fly—has 500 times the heat-retention effect compared to usual, suggesting that the impact on climate change could be substantial. As space development advances and space tourism becomes a reality, such issues should be examined with greater specificity, and experts are sounding the alarm.

Disparities and inequality stemming from space development

We previously discussed environmental issues, but disparities and inequality in space development are also serious. Even though more countries possess satellites, only 11 countries (※5) have the ability to launch independently, and it is undeniable that countries with launch capabilities enjoy many advantages.

For example, by undertaking launches of 177 satellites for 19 countries over five years from 2018, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) earned approximately 94 million US dollars and 46 million euros in foreign currency. Among these 19 countries is the space superpower, the United States. In addition to private-sector launches from the U.S., plans exist for launches from India in cooperation between the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and ISRO. Various factors are involved, but ISRO’s reliability and high cost-effectiveness are major reasons.

Signing of a memorandum on cooperation between ISRO and Russia in space development (Prime Minister’s Office / Wikimedia commons [Government Open Data License – India (GODL))

Although there are exceptional examples of Global South (※6) countries with overwhelming presence like this, most of the Global South lags far behind in the space sector. In recent years, there have been cases of space powers cooperating with Global South countries on space development. Chinese companies plan to invest $1 billion to establish a space development hub in Djibouti, and in 2023 they signed a memorandum. A research satellite developed by Kenyan researchers was launched in 2023 aboard a SpaceX rocket from the United States. In January 2023, the African Space Agency was inaugurated, expected to serve as a foundation for Africa’s space development. In today’s society, information and technology derived from space development are essential in every aspect, including daily life. As a result, countries in the Global South currently have to pay exorbitant fees to foreign governments to access these, further widening the wealth gap. However, compared to investing from scratch in domestic space infrastructure, there is often no choice but to depend on other countries. As the launch process channels funds to countries that already have capabilities, their space development capacity is strengthened further, and disparities become more pronounced.

This is not unique to the space industry, but correcting disparities once they arise is not easy. Based on lessons from Earth, a potential future disparity could stem from the tension between addressing space environmental issues and the desire of some countries to advance development. Suppose that, to halt environmental destruction in space, development is regulated or greener methods are required. Then the question arises whether space powers responsible for past environmental damage should bear primary responsibility—applying a principle like “common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR),” used in the climate change context—or whether uniform regulations should be applied to all countries. If such regulations or costly green development are demanded uniformly, low-income countries will face higher barriers to entering space, allowing early-developing powers to pull further ahead and increasing disparities. This has already sparked major controversies in responding to climate change; when the stage shifts to outer space, what conclusions will be reached?

Potential competition over space resources

We have explained past space development and current issues. Space development will likely advance further. Here we consider one potential debate: the issue of space resources. For example, it has been found that the Moon contains various resources, one of which, helium-3, is considered highly useful as a nuclear fusion fuel; it is scarce on Earth but abundant on the Moon. Although the Outer Space Treaty prohibits national appropriation of outer space and celestial bodies, this is a ban only on national appropriation; in recent years, some countries have been establishing domestic legal frameworks to lay the groundwork for sending private companies to acquire space resources (※7).

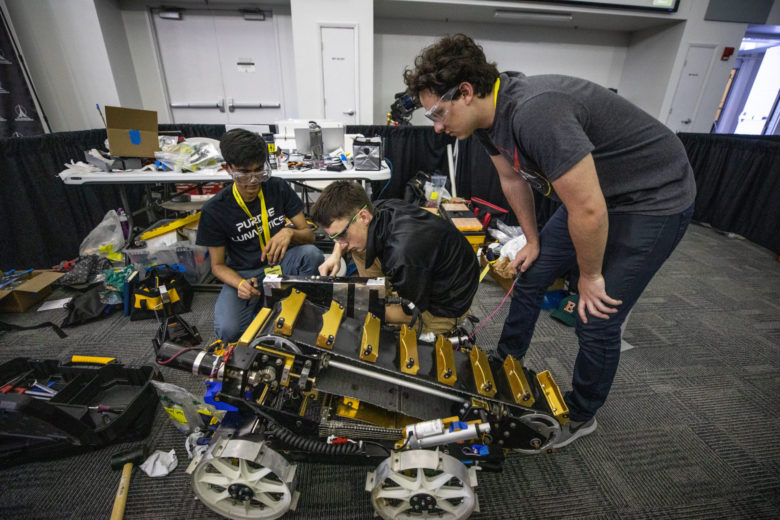

History is full of conflicts over resources, and such disputes are entirely possible. While collection is currently conducted primarily for scientific research, a shift to full-scale commercial activity would bring new problems. There are also questions about whether a small number of countries or companies should be allowed to monopolize space resources if the “common heritage of mankind (CHM)” principle, established in the Moon Agreement, is applied to countries without access to technology. In any case, few space powers have joined the Moon Agreement, so it has been largely dormant. Therefore, discussions are expected to continue across various layers—international, national, corporate, and individual.

A university team participating in a robotics competition for lunar resource extraction (NASA Kennedy / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Conclusion

We have discussed outer space from various perspectives. Space has given humanity new hope while also presenting many challenges and issues to be solved. We hope that careful discussion will lead to the optimal choices for humanity, and we will continue to monitor developments closely.

※1 The United States’ GPS, the EU’s Galileo, Russia’s GLONASS, and China’s BeiDou Navigation Satellite System, among others.

※2 Remote sensing is a technique for obtaining information about terrain and the atmosphere by measuring emitted and reflected radiation from satellites and aircraft.

※3 Outer Space Treaty Article 4: “States Parties to the Treaty undertake not to place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction, install such weapons on celestial bodies, or station such weapons in outer space in any other manner. The Moon and other celestial bodies shall be used by all States Parties to the Treaty exclusively for peaceful purposes. The establishment of military bases, installations, and fortifications, the testing of any type of weapons, and the conduct of military maneuvers on celestial bodies shall be forbidden. The use of military personnel for scientific research or for any other peaceful purposes shall not be prohibited. The use of any equipment or facility necessary for peaceful exploration of the Moon and other celestial bodies shall also not be prohibited.”

※4 1967 “Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space”

1972 “Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects”

1975 “Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space”

1979 “Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”

※5 After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Ukraine and the Russian Federation also succeeded in launches, but since their space programs were continuations of the Soviet program, they are not counted here.

※6 The Global South is a term used largely synonymously with “Third World” or “low-income countries” and does not literally mean countries located in the Southern Hemisphere.

※7 Countries that have established such domestic laws include the United States (2015), Luxembourg (2017), the United Arab Emirates (2019), and Japan (2021).

Writer: Yusui Sugita

Graphics: Yusui Sugita

0 Comments