In the Russia-Ukraine conflict, it became clear in 2022 that in 12 December Ukraine asked the United States to supply cluster munitions and that the U.S. was considering it. However, Japan’s three major newspapers—Asahi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun, and Mainichi Shimbun—made no mention at all of this consideration, let alone the fact that Ukraine has used cluster munitions in this conflict. By contrast, when Russia used cluster munitions against Ukraine in the same conflict, all three papers reported on it multiple times, mixing in strong criticism.

Although it is the same weapon, these two cases reveal a difference in how cluster munitions are treated. What exactly is this weapon? How has Japanese media viewed it? And does coverage change depending on whether a country used it or was targeted by it, as with Russia and Ukraine? We analyzed coverage by Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun.

Unexploded submunitions scattered on the ground, Iraq (Photo: Cluster Munition Coalition / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

目次

About cluster munitions

Cluster munitions are weapons that contain numerous submunitions within a single parent munition. When fired, they release these submunitions in midair, inflicting indiscriminate attacks over a wide area. They were first used during World War II and since then have been used by more than 20 countries. The United States used them extensively in Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq, among others. In 2006, Israel used them on a massive scale in Lebanon.

At first glance, they may not seem so different from conventional bombs, but in fact there is an international convention that bans the production, possession, and use of this weapon. What lies behind this? Among the submunitions released by this weapon, many fail to explode and remain as duds, and like landmines, they continue to pose a risk of detonation even after conflicts end. In other words, they harm both soldiers and civilians, in both wartime and peacetime. In affected areas, even after a conflict ends, children continue to be killed after mistaking duds for toys, and residents are prevented from freely using fields and land, delaying postwar reconstruction. According to statistics from the mid-1960s to the end of 2021, deaths from duds caused by cluster munitions are about four times higher than direct deaths ( ※1 ).

Because of these characteristics, a global movement emerged to ban the production, possession, and use of cluster munitions. First, in 2006 11, discussions were held within the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) on regulating cluster munitions, but opposition from stockpiling countries, including the United States and Russia, prevented agreement. In response, following the precedent of anti-personnel landmines, which were banned by treaty in 1999 ( ※2 ), a group of like-minded countries led by Norway and various NGOs drove the creation of a new treaty. The Convention on Cluster Munitions was adopted in 2008 and entered into force in 2010. It is commonly known as the Oslo Convention. As of August 1, 2022, 110 countries had joined and 13 had signed. Since the treaty entered into force in 2010, there have been no confirmed instances or allegations of new use by states parties as of 2023. In addition, the treaty has achieved certain results by deterring even non-parties from using these weapons and by helping to create an international trend toward restricting investment and financing related to cluster munition producers. However, as of August 2022, multiple stockpiling countries, including the United States, Russia, China, and India, remained non-parties, and their use or potential use remains a problem.

A 12-year-old boy who lost his leg, Lebanon (Photo: luster Munition Coalition / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Use since the treaty entered into force

Since the Convention on Cluster Munitions entered into force in 2010 August, no use by states parties has been confirmed, but non-parties Thailand, Libya, Syria, Sudan, South Sudan, Ukraine, Saudi Arabia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia have used them ( ※3 ). Let us look in turn at where these countries used cluster munitions.

In 2011 2, during a border conflict with Cambodia, Thailand reportedly used cluster munitions against Cambodia.

Cluster munitions were used in Libya in 2011, 2014, and 2019. In 2011, it was revealed that government forces loyal to Muammar Gaddafi used cluster munitions against opposition forces. After the collapse of the Gaddafi regime, from 2014 12 onward, evidence was found at at least 2 sites in the country indicating cluster munitions had been used, although the users could not be identified. Furthermore, in 2019, there were multiple instances of use and possible use by units belonging to the anti-interim government “Libyan National Army.”

In Syria’s ongoing conflict since 2011, from mid-2012 the Syrian government forces or the Russian forces supporting them used cluster munitions, with further use confirmed in 2022. In the latter part of 2014, IS (the Islamic State), which controlled part of Syria, also used cluster munitions.

In 2012 and 2015, Sudanese government forces used cluster munitions in fighting against anti-government forces. The Sudanese government participated in the negotiations and adoption of the Convention on Cluster Munitions and previously stated its intent to sign, but as of 2023 1 it remains a non-party.

In 2014, cluster munitions were used in conflict-torn South Sudan. The user has not been identified.

In the 2014–2015 conflict, both Ukrainian government forces and Russian-supported Ukrainian anti-government forces used cluster munitions in eastern Ukraine.

In the Yemen conflict, from 2015 to 2017, the Saudi-led coalition used cluster munitions in airstrikes against Houthi forces.

In 2020, in the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, both Armenia and Azerbaijan used them.

Since the Russia-Ukraine conflict erupted in 2022 2, both Russia and Ukraine have used cluster munitions.

The 10th meeting of the Convention on Cluster Munitions (Photo: Cluster Munition Coalition / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Cluster munitions still stockpiled and produced

As described above, due to their indiscriminate nature and long-lasting harm, the use of cluster munitions is considered problematic and there is a treaty banning them. Even so, many countries that have not joined the convention continue to stockpile them, and some states parties have yet to complete destruction.

What about Japan? Japan, which has stockpiled cluster munitions, was involved from the drafting stage of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, signed it in 2008 12, and ratified it in 2009 7. By 2015 2, it had completed the disposal of cluster munitions previously held by the Self-Defense Forces. However, Japan allows the introduction and use of cluster munitions by U.S. forces stationed in Japan. Responding to U.S. pressure against strict provisions, Japan negotiated during the treaty drafting to ensure the text would not impede U.S. forces’ activities in Japan; when that failed, it unilaterally declared its own interpretation at the conference. As a result, U.S. forces in Japan were able to continue bringing in and using cluster munitions. This came to light through U.S. diplomatic cables published by the whistleblowing site WikiLeaks.

Behind stockpiling lies production. Among non-parties to the convention, several countries still produce cluster munitions or retain the potential to do so. Production is carried out by numerous companies and supported by financing from many financial institutions. In the past, four Japanese financial institutions—Dai-ichi Life, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group, and ORIX—were also involved in investing in and financing producers. Furthermore, in 2017 it was revealed that the Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF), which manages Japan’s public pensions, held shares in cluster munitions producers. As of 2021 3, the fund was still found to hold shares in companies producing or that had previously produced these weapons at that time.

Israeli-made cluster munition (Photo: aick / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 3.0])

Cluster munitions and media coverage in Japan

Given that Japan has joined the Convention on Cluster Munitions while at the same time preserving U.S. forces’ cluster munitions in Japan, and that Japanese financial institutions have been involved—past or present—in producing these weapons through investment and financing, how has this been reported domestically? We examined articles that mentioned cluster munitions in Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun since the convention entered into force on 2010 8 1 ( ※4 ).

In Yomiuri Shimbun, we observed a reporting stance that seemed to exclude facts unfavorable to the home country. There was one article that mentioned the exchanges between the U.S. and Japan revealed by WikiLeaks, but this piece (※5) focused on portraying WikiLeaks itself as problematic and criticizing it for “endangering diplomacy,” and said little about the series of cluster munitions–related events that could be considered inconvenient for Japan. In contrast, an article (※6) reporting that the United States had secretly pressured Afghanistan to allow the use of cluster munitions treated WikiLeaks as a legitimate source, without questioning or criticizing it at all. Despite being the same source, Yomiuri’s stance appeared to shift to questioning the source’s reliability when the revelations were unfavorable to Japan. Moreover, there were no articles directly covering investment and financing by Japanese financial institutions in cluster munition producers. In one article ( ※7 ), for example, it stated, “MUFG Bank is expected to finalize by May a lending policy that prioritizes public interest, such as encouraging financing for ultra-high-efficiency coal power projects and prohibiting financing for companies that produce cluster munitions,” thus deftly avoiding any mention that problematic investments had been made in the first place.

By contrast, Asahi Shimbun and Mainichi Shimbun could be said to have offered coverage that was relatively reflective of reality. There were two articles in Asahi and 1 in Mainichi that mentioned the series of events surrounding the preservation of U.S. forces’ cluster munitions in Japan revealed by WikiLeaks ( ※8 ), and none of these articles attempted to shield Japan. As for investment and financing, there were 6 articles in Asahi and 4 in Mainichi that mentioned the topic, indicating a certain degree of attention. Notably, all 6 Asahi articles used critical wording such as “inhumane cluster munitions” or “cluster munitions that scatter small bomblets over a wide area,” and included pieces criticizing the fact that four companies—the largest number among states parties to the convention—had invested in or financed producers, as well as a reader’s letter lamenting Japanese financial institutions’ investment in and financing of cluster munition producers ( ※9 ).

Disposal detonation of unexploded ordnance, Laos (Photo: Cluster Munition Coalition / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Coverage biased by who uses the weapon: Asahi Shimbun and Yomiuri Shimbun

Next, let’s see how Japan’s three major newspapers reported on the use of cluster munitions. We examined articles in Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun that mentioned the use or possible use of cluster munitions since the convention entered into force on 2010 8 1 ( ※10 ). There were 15 articles in Asahi, 32 in Mainichi, and 13 in Yomiuri. To understand the context in which the articles were written (※11) and the extent of criticism they contained, we developed criteria for assessing the level of criticism ( ※12 ) and used these for the analysis.

Among the three, Asahi and Yomiuri showed particularly pronounced bias. In the Russia-Ukraine conflict, these two papers overwhelmingly reported Russia’s use against Ukraine (Asahi: 6 of 15 articles; Yomiuri: 8 of 13). Moreover, in all of its articles ( ※12 ), Asahi used strongly critical language such as “inhumane weapon,” “a weapon that indiscriminately and widely kills and injures people,” and “brutal.” Yomiuri also included at least moderate criticism in all of its articles ( ※13 ), with wording such as “cluster munitions banned by international treaty.” In contrast, in the same conflict, neither paper reported at all on Ukraine’s use. Nor did they report on Ukraine’s use in eastern Ukraine in 2014. Despite being the same weapon, Russia’s use drew extensive and critical coverage, while Ukraine’s use was not mentioned.

Furthermore, articles reporting use in Syria were less than half the number of those reporting Russia’s use against Ukraine (Asahi: 3 articles; Yomiuri: 3 articles). The Syrian conflict is larger in scale, and cluster munitions have been used over a longer period since 2012. By comparison, judging by death tolls alone, the Russia-Ukraine conflict is smaller in scale than the Syrian conflict, and Russia’s use of cluster munitions against Ukraine is a phenomenon only since 2022 2.

Similarly, the Yemen conflict is larger in scale than the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and cluster munitions were used for a prolonged period from 2015 to 2017, based on what is known. Nevertheless, use by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen was almost not reported (Asahi: 1 article; Yomiuri: 1 article).

Other cases—Thailand, Libya, Sudan, South Sudan, and Armenia and Azerbaijan—were also barely covered ( ※14 ).

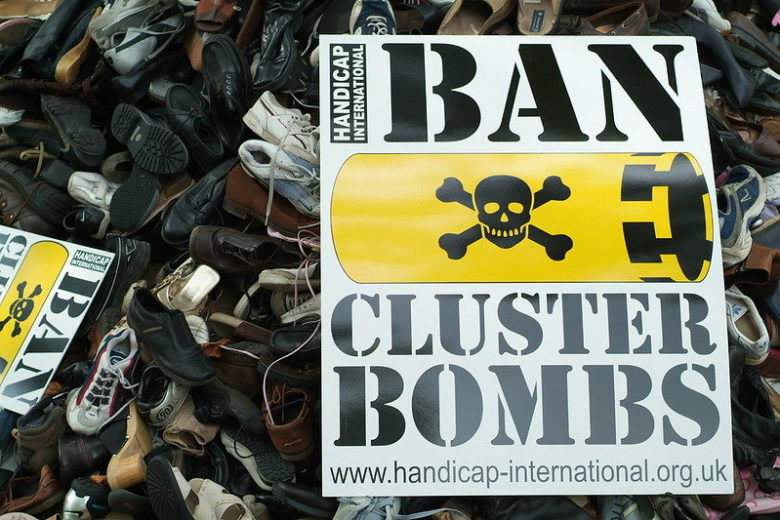

“Ban cluster bombs!” A protest displaying shoes symbolizing injuries caused by unexploded ordnance (Photo: S Pakhrin / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Coverage biased by who uses the weapon: Mainichi Shimbun

Compared with the other two papers, Mainichi Shimbun achieved a somewhat better regional balance. The country it mentioned most was Syria ( 13 of 32 articles ). Given the scale of the Syrian conflict and the prolonged use of cluster munitions there, this is more balanced. In contrast with the other two papers, coverage of Russia’s use against Ukraine in the Russia-Ukraine conflict was limited to 3 articles. In addition, the paper mentioned Thailand’s use in 2 articles, Libya’s in 6, Ukraine’s 2014 use in 3, and the Saudi-led coalition’s use in Yemen in 3, providing somewhat broad coverage.

That said, Mainichi also did not mention at all Ukraine’s use against Russia in the conflict that began in 2022. Moreover, looking at the content, when Russia used cluster munitions against Ukraine, two of the three articles used strongly critical terms such as “a massive humanitarian catastrophe” and “outrage” ( ※15 ), whereas when Ukraine used them in eastern Ukraine in 2014, there was little critical framing—only one of the three articles contained weak criticism ( ※16 ).

Conclusion

As we have seen, Japanese reporting on cluster munitions does not necessarily reflect the realities at home or around the world. Why does such bias emerge? While it is difficult to be categorical given differences across conflicts and in how cluster munitions were used, we may be able to identify the following pattern. With variations across newspapers, overall there is a tendency to report more on and to criticize more heavily countries such as Russia and Syria that are “enemy” in the eyes of Japan or the West, cast as the “villains” in a morality play. By contrast, when close partners of the Japanese government such as Saudi Arabia use them in Yemen, or when Ukraine uses them, there is little attention or criticism. And when it comes to places like Sudan or Libya, where the Japanese government appears to have less strong interest, usage seems to attract little attention as well.

However, if we treat weapons like cluster munitions as “inhumane,” then whoever uses them should be treated as using an “inhumane” weapon. Biased reporting of this kind fails to convey the realities of the world and may be perceived as indirectly taking sides in a conflict. Is Japanese reporting acceptable as it is?

U.S. service members preparing cluster munitions for a fighter jet (Photo: U.S. Indo-Pacific Command / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

※1 From the mid-1960s to the end of 2021, out of the total number of casualties 23,082 worldwide from cluster munitions, 4,656 were caused directly by cluster munition strikes and 18,426 were caused by duds.

※2 The Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention (the Ottawa Convention) was achieved under the leadership of Canada and other like-minded countries and the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL).

※3 Mainly cases where there is solid evidence indicating use.

※4 Using the three papers’ databases (Asahi: Kikuzo Cross Search; Mainichi: Maisaku; Yomiuri: Yomidas Rekishikan), we searched the Tokyo editions (morning and evening) of the national and metropolitan sections. The period was from 2010 8 1 to 2022 12 31. In each database, we searched for articles containing the keyword “cluster munitions” and analyzed all hits. One Yomiuri article could not be viewed due to copyright restrictions and was excluded.

※5 “WikiLeaks threatens diplomacy: U.S. diplomatic cable dump—current situation and problems—undermines the premise of confidentiality” (Yomiuri Shimbun, June 23, 2011)

※6 “Ripples in Afghanistan: WikiLeaks—U.S. pressed ‘accept cluster munitions’—pressure by previous administration” (Yomiuri Shimbun, December 6, 2010)

※7 “Tightening financing for coal-fired power: major banks weigh limits based on CO2 emissions” (Yomiuri Shimbun, 2018 5 12)

※8

“U.S. worried about Japan joining treaty: ‘would constrain U.S. forces’—diplomatic cables on the cluster munitions ban” (Asahi Shimbun, 2011 6 16)

“Two faces of Japanese officials: joined the cluster ban treaty while repeatedly making discouraging statements to the U.S.—diplomatic cables” (Asahi Shimbun, 2011 6 16)

“WikiLeaks: Japanese government discussed preserving cluster munitions—publishes U.S. diplomatic cables” (Mainichi Shimbun, 2011 6 16)

※9

“Japan tops among treaty countries with four firms investing in cluster munition producers—NGO report” (Asahi Shimbun, 2017 5 24)

“(Voices) Stop investment and financing for bomb manufacturers” (Asahi Shimbun, 2017 6 5)

※10 Using the three papers’ databases (Asahi: Kikuzo Cross Search; Mainichi: Maisaku; Yomiuri: Yomidas Rekishikan), we searched the Tokyo editions (morning and evening) of the national and metropolitan sections. The period was from 2010 8 1 to 2022 12 31. In each database, we searched for articles containing the keyword “cluster munitions” and analyzed those that reported or mentioned use or possible use since 2010 August.

※11 When a single article mentioned multiple contexts of use, each context was counted as one article. For example, “Cluster munitions: 97% of victims are civilians—417 casualties last year—Syria and Yemen stand out—NGO report” (Mainichi Shimbun, 2016 9 3) was counted as one article on Syria’s use, one on use by Saudi forces in Yemen, and one on use in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

※12 Based on the language used, articles were categorized as “strongly critical,” “moderately critical,” or “weakly critical.”

“Strongly critical” articles included language that could be taken as direct and emphatic criticism. For example: “outrage,” “extremely dangerous/highly lethal,” “brutal/brutality/cruel,” “inhumane,” “indiscriminate attack/amounts to a war crime,” etc.

“Moderately critical” articles mentioned denunciations or concerns expressed by someone (government officials, human rights groups, the international community, etc.), or included wording such as “also injures civilians/causes civilian casualties,” “banned from use/widely banned/internationally banned/banned by international treaty,” “causes widespread harm,” etc.

“Weakly critical” articles included language that could be seen as indirect criticism. For example: “suspected of ~,” “used repeatedly,” “at any cost,” “damage/victim/casualty,” etc. Articles that appealed to readers’ sympathy by describing the harm or the circumstances of victims were also categorized as “weakly critical.”

※13

“(Editorial) Russia’s invasion—immediate halt to humanitarian crimes” (2022 3 16)

“(Ukraine invasion) Lives and cities disappearing—intensifying east, fears of prolonged war” (2022 4 24)

“Cluster munitions? Slavyansk mayor posts” (2022 7 3)

“Cluster munitions used? Southern Ukraine—by Russian forces” (2022 7 30)

“UN: ‘Russia committing war crimes’—torture and sexual assault of a 4-year-old confirmed” (2022 9 24)

“Crosses marked only with numbers in the woods—Izyum cemetery probe, ‘scars on the heart’—Ukraine” (2022 9 25)

※14

On Thailand’s use: Asahi: 1 article; Yomiuri: 0 articles

On Libya’s use: Asahi: 2 articles; Yomiuri: 1 article

On Sudan’s use: Asahi: 0 articles; Yomiuri: 0 articles

On South Sudan’s use: Asahi: 0 articles; Yomiuri: 0 articles

On Armenia and Azerbaijan’s use: Asahi: 2 articles; Yomiuri: 0 articles

※15

“Ukraine invasion: ‘Accept people seeking peace’—appeal by Ukrainians in Japan” (2022 3 4)

“This week’s bookshelf: ‘To you who don’t know the Iraq War’ = edited by the Network Calling for an Iraq War Inquiry” (2022 4 9)

※16 An article that appealed to readers’ sympathy by describing the harm and victims’ circumstances.

“Ukraine: Residents in the east (Part 2, end)—Civilians in distress, rations keeping people alive” 2015 3 16

Writer: Yuka Funai

0 Comments