Between 1964 and 1973, in parallel with the Vietnam War, Laos was bombed by the United States. The number of air raids was about 580,000. Astonishingly, that translates to a bombing every eight minutes for nine years. The amount of ordnance dropped exceeded two million tons. Calculated against Laos’s population at the time, one ton of bombs was dropped per person. Laos is “the most heavily bombed country per capita” in the world.

The aftereffects persist to this day. Unexploded ordnance (UXO) left in the soil remains a problem even now, roughly 40 years after the war. Moreover, because there is an overwhelming amount of duds, cluster bomb casings, and other bomb debris left by the bombing, especially in rural areas there is a “bomb scrap business” in which people use the remnants as household items as-is, or rework them into spoons and accessories to sell to tourists for income. However, the people handling the bombs are not specialists; most are villagers without expert knowledge. Villagers and children are at risk of UXO accidents while collecting bomb debris or during reprocessing. Yet for people living in impoverished areas, using UXO has become a source of livelihood that cannot be easily given up.

Cluster bomb casing reused as a planter (Giovanni Diffidenti/Flickr) [CC BY 2.0]

Historical background of the bombing

Laos, which had been under French colonial rule, gained independence in 1953. However, after independence, conflict broke out over political control between the Royal Lao Government and the communist Pathet Lao. The U.S. government supported the royal government and opposed the Pathet Lao. At the same time, the Vietnam War was underway in neighboring Vietnam, with U.S.-backed South Vietnamese forces fighting the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, backed by North Vietnam. During this period, North Vietnam supported the Pathet Lao while pressuring the royal government. The United States initially avoided direct military intervention; led by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), it provided guerrilla training to Lao mountain units to disrupt North Vietnamese operations in northern Laos. But as North Vietnam gained the upper hand in the Vietnam War, the U.S. carried out bombing in Laos in 1964 as part of covert operations.

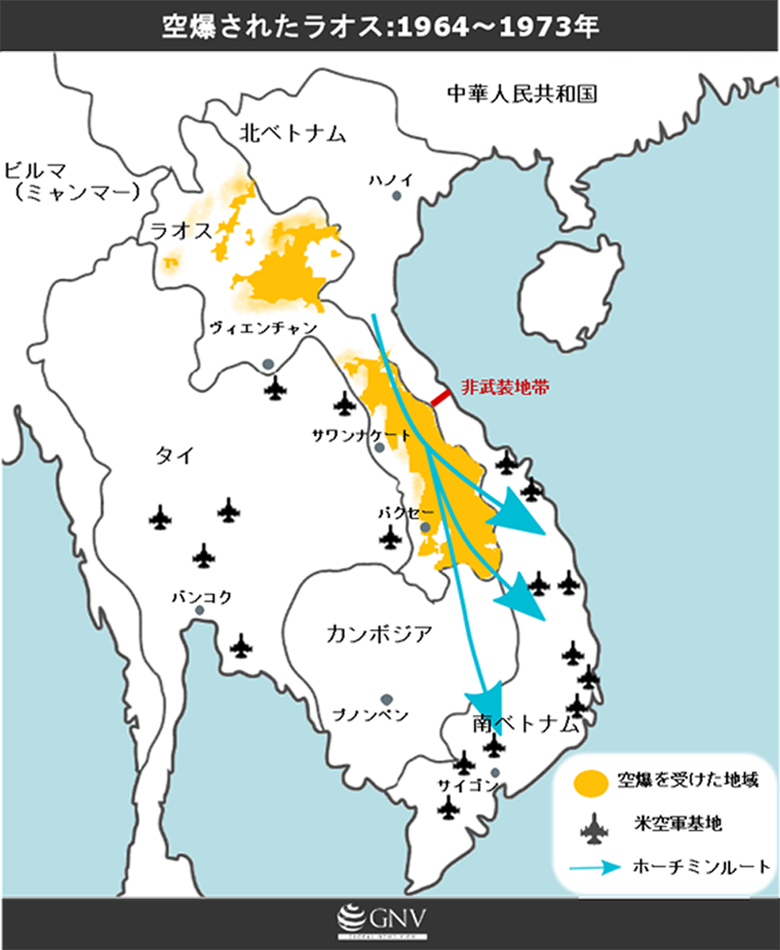

There were two main objectives. First, to attack the communist Pathet Lao. Given the Cold War context, the United States sought to prevent Laos from falling under communism through North Vietnamese influence. Second, to cut the “Ho Chi Minh Trail,” the route supplying troops and materiel from North Vietnam to the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam. The demilitarized zone separating North and South Vietnam was under extremely tight surveillance, making support via the DMZ impossible. North Vietnam therefore used the “Ho Chi Minh Trail”—a network of mountain paths through Laos and Cambodia—to reach South Vietnam. With the covert operations in Laos, the CIA evolved from a very small intelligence agency into a powerful quasi-military organization.

Laos was also used as a dumping ground for bombs. When U.S. bombers flying from bases in Thailand to Vietnam could not strike their intended targets, they could not land with their bombs still onboard, so they jettisoned them over Laos on the way back.

Based on UXO-NRA’s bombing data map

The current state of UXO

The major driver of UXO is cluster munitions. A cluster bomb contains hundreds of small bomblets that are dispersed in the air. Not all of these bomblets explode, and many duds are created. In Laos, between 1964 and 1973, about 270 million bomblets from cluster munitions were dropped. Of these, about 80 million—roughly 30%—remain in the country. More than 50,000 people were affected by UXO between 1964 and 2008, of whom 20,000 were victims after the war. Forty percent of the 50,000 victims are children. UXO can be small and look like toys, making children more vulnerable than adults. The damage is not only human. The presence of UXO in the soil raises the cost of land use and increases risks during development. As a result, land use is restricted, and infrastructure development and agricultural activity are constrained. As for agriculture, most households must farm despite the danger.

According to the Lao government agency’s 2015 annual report, the total number of victims in 2008 was 302. The number has been decreasing year by year, and since 2013 it has remained below 50. The UXO clearance and risk education conducted by NGOs and others can be said to be producing results. Nevertheless, less than 1% of UXO has been cleared or destroyed in the 40 years since the war. There remains the reality that over half of the world’s casualties from cluster-munition UXO occur in Laos.

Small UXO left from a cluster bomb (Steve Joyce/Flickr) [CC BY 2.0]

Measures to address the problem

In 1996, with assistance from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Lao government established UXO Lao as a state-run UXO clearance agency. Not only state agencies but also NGOs and international organizations play major roles in addressing the UXO problem. Examples include the Mines Advisory Group (MAG), which conducts UXO and landmine clearance in more than 40 countries, and the demining NGO HALO Trust, founded in the United Kingdom. These organizations contribute not only to clearance but also significantly to risk education about UXO. Furthermore, in 2005 the state regulatory body UXO-NRA was established to oversee UXO clearance activities broadly across both governmental and non-governmental actors. According to the agency’s 2015 annual report, more than 250,000 people received risk education that year.

The United States provided an average of $4.9 million per year in assistance from 1993 to 2016. However, this amount is far from sufficient; the gap is clear when you consider that about $13.3 million was spent per day during the bombing. There was a new development in U.S. support in 2016. President Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit Laos, stating, “Given the history between Laos and the United States, America has a moral obligation to help Laos,” and pledged $30 million per year for UXO clearance over the next three years. Compared to the pre-2016 annual average of $4.9 million, this is a substantial increase.

Demining activities (Steve Joyce/Flickr) [CC BY 2.0]

The remaining problems with cluster munitions

In response to cluster munitions, which cause devastating harm far into the future, international moves to regulate them have intensified. The prime example is the Convention on Cluster Munitions, signed in 2008 and entering into force in 2010. Building on the achievements and momentum of the Mine Ban Treaty, the efforts of the Cluster Munition Coalition—a network of more than 200 civil society organizations and NGOs worldwide—also contributed. The treaty comprehensively bans the possession, production, use, and transfer of cluster munitions, and 94 countries have ratified it to date. However, challenges remain, including the absence of major powers such as the United States, China, and Russia. Moreover, although the treaty obliges states parties to discourage the use of cluster munitions by non-signatories, since 2010 the use of cluster munitions has been confirmed in seven non-states parties, most notably in Yemen and Syria.

While there was significant movement in U.S. support for Laos, the U.S. Department of Defense announced a new policy on cluster munition use in 2017, revealing a likelihood of rescinding the previous plan that required ending the use of cluster munitions by 2019. The memo stated that “until sufficient quantities of enhanced and more reliable munitions are fielded to replace current cluster munitions, cluster munitions will be retained as an effective and necessary capability.”

In Laos and elsewhere around the world, UXO lying dormant continues to cause harm. Laos’s UXO problem may improve thanks to the efforts of the Lao government, international organizations, and NGOs, as well as increased U.S. assistance. Yet the reality is that less than 1% of UXO has been cleared. Globally, despite progress through treaty-making, many major powers are reluctant to relinquish cluster munitions because of their perceived power and effectiveness. The road to eliminating cluster munitions, which are still being used today, remains long.

Laos: View of Pakbeng village (Clay Gilliland/Flickr) [CC BY 2.0]

Writer: Eiko Asano

Graphics: Hinako Hosokawa

はじめまして, 私はラオス生まれ, 3才の時, 両親とラオスから逃げ出し, その後タイ▶台湾▶日本とフランスに移住した難民・華僑です, 最近こちらの記事を拝見させていただき, 当時のラオスの大変さや, 両親の苦労を今知りました, 素晴らしい記事をありがとうございました

ラオスの方々に苦しみが伝わってきます。大変勉強になりました。ありがとうございます。