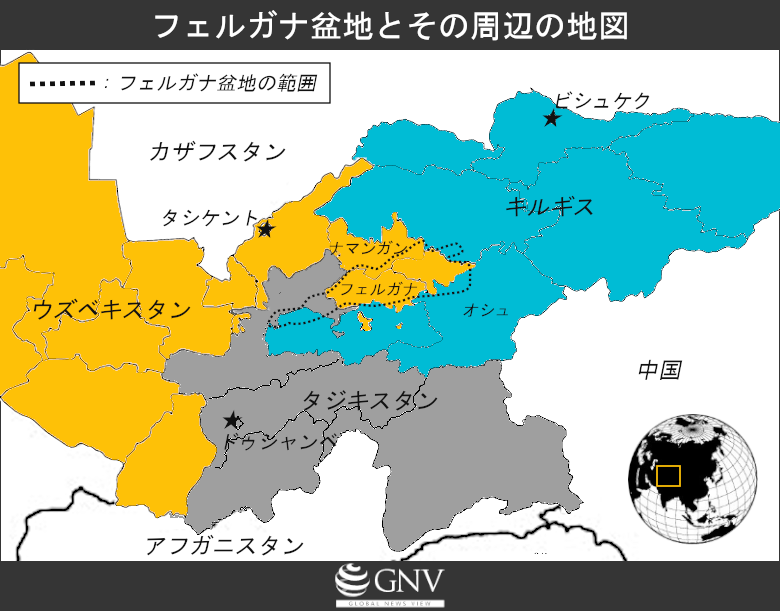

On September 14, 2022, a military clash broke out between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, and over the following week at least more than 100 people, including 37 civilians, were killed. However, this was not the first time the two countries have been in conflict. Nor is the conflict confined to just Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Behind the latest fighting lies the region known as the Fergana Valley, which spans Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, and, more broadly, the instability of Central Asia. This article looks at the issues that create such instability.

One of the mountain ranges surrounding the Fergana Valley, the Kurama Range (Photo: Daniel Mennerich / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

目次

Historical developments

First, let’s look at the Fergana Valley, the main stage of this article. The Fergana Valley belongs in part to each of three countries: Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Geographically, it is a basin of about 22,000 square kilometers surrounded by the Chatkal and Kurama Ranges to the northwest, the Fergana Range to the northeast, and the Alay and Turkestan Ranges to the south. Although precipitation is low, rivers and well-developed irrigation support the production of crops such as cotton and fruit, as well as raw silk.

The region was an important relay point on the Silk Road, where merchants traveling in camel caravans thrived. In addition to trade in goods, cultural exchange flourished, and Chinese pottery and weaving techniques advanced. Its geopolitical characteristic of being surrounded by mountain ranges served as a natural defensive barrier, making the valley relatively peaceful compared to surrounding areas and giving residents a somewhat higher standard of living. These factors attracted many migrants to the valley. Historically, the region was incorporated into unified political entities such as the Persian Empire, the Mongol Chagatai Khanate, the Khanate of Kokand, and the Russian Empire, without internal borders, allowing people to move freely to surrounding areas. As a result, the Fergana Valley became a mosaic of people with diverse backgrounds.

Around 1920, the valley came under Soviet rule. Guided by the idea that a “community of people” should possess a “common language, territory, economic life, and culture,” the Soviets sought to create autonomous republics and regions within the USSR on that basis (Note 1). This led to the division of what had been a contiguous Fergana Valley into three parts—today’s Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. However, at the time all three were part of the USSR, and internal borders functioned only weakly, so this did not pose a major problem.

After the Soviet Union collapsed and the states became independent in 1991, national borders began to function in practice. The problem was that the borders each state adopted were ambiguous. The Soviets had revised borders repeatedly, and each state chose the version most favorable to itself. In the immediate post-independence period, border management was not yet strict, and people and goods could move relatively freely across borders. At the same time, some Central Asian countries found themselves in unstable situations amidst an unanticipated independence. For example, Tajikistan experienced a large-scale armed conflict that lasted five years starting in 1992, in which politicians, local power brokers, extremist groups, and other competing interests joined the fight for control over the newly independent state, its resources, and its trajectory. Between 40,000 and 120,000 people are estimated to have died before the conflict ended in 1997.

A dump truck burned during the conflict in Tajikistan (Photo: Brian Harrington Spier / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0])

In Uzbekistan, a bombing targeting the president occurred in the capital Tashkent in 1999 (Note 2). The government attributed the attack to extremists and, to prevent their infiltration, tightened border controls by laying landmines. This also served the goal of protecting the protectionist economic policies pursued at the time. Known as a landmine policy, it killed dozens of civilians (Note 3).

By contrast, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan adopted a more relaxed border management regime. Between 2002 and 2021, only about 500 kilometers of the 970-kilometer boundary between the two countries were demarcated. It has been suggested that the two governments, eager to keep relations on an even keel, had little interest in finalizing the border. In fact, a frequent pattern of disputes in the region was for a conflict to start at the resident level, escalate to the point that border guards were deployed, and then, without addressing the root causes, for representatives to reach a provisional agreement and ceasefire—meaning the state was not always actively involved from the start.

Since the 2000s, however, both countries’ approaches to the border appear to have changed. From 2003 to 2013, border management was tightened. It has been argued that this made residents who committed minor infractions or scuffles—previously overlooked—targets of border forces, creating conditions more prone to military clashes. Such confrontations in turn led both countries to further beef up their border forces, creating a vicious circle.

Yet the ambiguity of the border and stricter border management are not the root causes of conflict in this region. Rather, issues spanning the Fergana Valley—and indeed Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan—have destabilized the area, with border disputes then acting as flashpoints. We consider these issues under poverty, politics, extremism, and drugs. Water is also a major issue in the region; for that, please refer to GNV’s previous article.

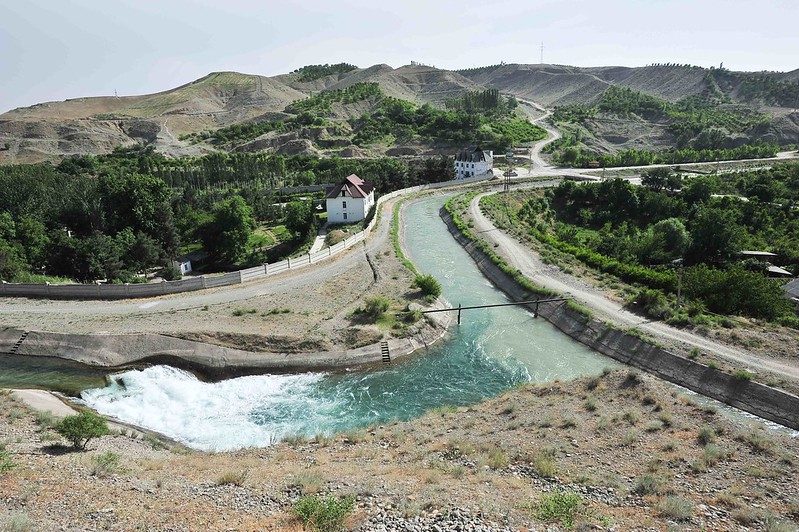

A canal flowing through the Fergana Valley (Photo: IWMI Flickr Photos / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Poverty

We begin with the poverty situation in the Fergana Valley. Here we define the poverty rate as the share of people living on US$5.50 a day or less (Note 4). In 2019–2020, many areas of Kyrgyzstan’s portion of the valley had a poverty rate of 74% to 84%. Given that Kyrgyzstan’s national poverty rate in 2019 was 53%, it is clear that the Fergana Valley has particularly high poverty rates. Reports also indicate that poverty levels are high across the valley beyond Kyrgyz territory as a whole.

To analyze the valley’s poverty problem, we first look at Central Asia’s overall poverty and then at the specific factors driving poverty in the Fergana Valley.

Understanding poverty in Central Asia requires tracing developments from the Soviet era. For regions of Central Asia, the Soviet central government was a major source of revenue, and Russia, the Soviet core, was a key market, indeed. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Tajikistan is estimated to have received transfers equivalent to about 40% of GDP from the Soviet government.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Central Asian states lost Soviet funding and the benefits of intra-Soviet trade. With few domestic revenue sources beyond banking and limited access to international markets, they were urged to pursue fiscal reforms to stabilize their finances. As part of this, governments in many countries cut spending such as subsidies to state-owned enterprises. Reduced government outlays and restricted market access dramatically reduced output in the region. Many industrial firms, having lost Russia as their traditional market, were unable to compete under new market conditions. Even cotton cultivation, a regional mainstay, has ceased to be a stable source of income due to global declines in cotton prices.

Cotton cultivated in the Fergana Valley (Photo: Peretz Partensky / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Now to the factors that make the valley particularly poor. Today the Fergana region is the most densely populated in Central Asia, with a population density said to be 12 times that of Kyrgyzstan’s national average. Such overcrowding has led to shortages of resources such as land and water and to higher unemployment.

Moreover, not limited to the Fergana Valley, many young people from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan go to Russia as migrant workers to earn income. By 2014, the number of migrant workers from Central Asia in Russia was estimated at as many as eight million (Note 5). However, the 2009 global financial crisis, the 2014 depreciation of the Russian ruble, and Russia’s restrictions on foreign workers forced many to return, further exacerbating overcrowding in the valley.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, cross-border movement has been restricted and remittances from abroad have fallen, further deepening poverty. Although governments imposed cross-border restrictions, the ambiguity of the border and gaps in enforcement increased discretionary behavior and corruption among border officials, meaning small traders and residents needed bribes to move, according to one assessment.

As seen above, despite its natural endowments, the Fergana Valley has high levels of poverty due to region-wide economic decline compounded by factors such as overcrowding.

Political problems

Because of the complex history described earlier, communities in the Fergana Valley are highly diverse. It has been noted that politicians may seek to use nationalism and populist tactics to consolidate their power bases under such conditions. Here we consider several cases linking politics and conflict.

In 1990, large-scale clashes erupted in Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s second-largest city in the valley. Though Osh is in Kyrgyz territory, ethnic Uzbeks were the majority and wielded considerable economic power. As the number of ethnic Kyrgyz moving from the mountains into the valley grew, the Kyrgyz government implemented nationalist policies favoring ethnic Kyrgyz, fueling resentment among Uzbeks. Combined with unequal employment and political participation between communities, clashes broke out between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz. The death toll is at least 220 confirmed, with estimates ranging from 600 to 1,200.

In 2005, the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan forced President Askar Akayev to resign (Note 6). Under his successor, Kurmanbek Bakiyev, corruption and authoritarianism worsened. Bakiyev also favored the south of Kyrgyzstan, including the Fergana Valley, disadvantaging ethnic Uzbeks and northerners. In April 2010 in Bishkek, clashes between Bakiyev opponents and police left 85 people dead, leading to Bakiyev’s ouster. His supporters then began protests in the valley, and in June, clashes erupted between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks. The exact toll is unknown, but one claim puts the death toll at around 900.

Osh, one of the cities that witnessed the 2010 riots, at the time (Photo: Evgeni Zotov / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Meanwhile, many small-scale conflicts (Note 7) have occurred between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan in the valley. Since around 2012, the problem has worsened, with more than 150 incidents recorded in the following decade. Contributing factors include the limits of resources amid population growth on both sides of the border and stricter border enforcement. In recent years, however, the conflict appears to have further escalated. In 2021, a major military clash broke out, killing about 50 people. And in September 2022, as mentioned at the outset, a conflict erupted between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan that left more than 100 people dead. The rapid escalation suggests political factors beyond resource scarcity.

For example, some argue that the Tajik government deliberately sparked a foreign conflict to distract from domestic issues (Note 8). Kyrgyz officials have also claimed that Tajikistan sought to enlist Russia on its side. In recent years Kyrgyzstan has moved to build a railway with China and Uzbekistan to Europe that bypasses Russia and has taken a neutral stance on the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Given Kyrgyzstan’s equivocal posture toward Russia, Tajikistan may have seen an opportunity to align with Russia and gain an advantage, potentially making its approach to the conflict more assertive.

Extremism and excessive countermeasures

The presence of extremist groups is also a concern in the Fergana Valley. In 1992, the Adolat party, an extremist group, was formed in Namangan, a city in Uzbekistan’s part of the valley. Adolat sought to establish Islamic law in Uzbekistan based on an extreme interpretation, and members reportedly patrolled the city enforcing harsh rules and punishments. President Islam Karimov responded with a heavy hand, but one of the ringleaders, Tahir Yuldashev, moved to Tajikistan and continued attacks on Uzbekistan. The group also fought in the Tajik conflict that began in 1992. In 1998, Yuldashev and others founded the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) as Adolat’s successor. The IMU was described as dedicated to dismantling Uzbekistan’s political system and ousting President Karimov to establish sharia.

Namangan around 2005 (Photo: Farkhod Fayzullaev / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The IMU is believed to have been involved in the 1999 Tashkent bombings and the 2014 attack at Karachi Airport claimed by the Taliban. Many other extremist groups exist in Central Asia, but they are uncoordinated and have limited capacity, tending to be IMU offshoots or imitators of foreign groups such as al-Qaeda, according to one assessment.

Why is extremism active in the Fergana Valley? The area attracts extremists due to geographic, economic, socio-cultural, and external factors. Geographically, enclaves and inadequate border control meant fewer constraints on movement. Economically, there are many unemployed young people in the valley, noted to be more susceptible to extremist ideologies. Migrant workers seeking income may also have their identities damaged by low wages and poor living conditions abroad, making them more vulnerable to extremist influence, it has been argued. Socio-culturally, there has been a return to Islam after the atheism of the Soviet era, which may also bolster extremist currents.

External factors include the influence of neighboring countries. The valley is close to unstable regions such as Afghanistan and Pakistan. In the late 1990s the IMU allegedly received funding from Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and maintained ties with the Taliban, whom the ISI also supported, according to reporting. Radical elements from Saudi Arabia have engaged in outreach through education, building mosques, and disseminating extremist literature. Saudi Arabia has supported the spread of such ideology not only in the valley but worldwide, with funding totaling US$86 billion over the past 50 years.

Residents of Central Asia, including the Fergana Valley, have also traveled abroad and taken part in combat as extremists, documented in various reports. Exact numbers are unclear, but the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) estimates that more than 500 citizens from Uzbekistan joined Sunni extremist groups in Syria and Iraq. Kyrgyzstan’s Interior Ministry has confirmed that more than 500 of its citizens were in Syria and Iraq.

Beyond extremist activity itself, reactions to it also contribute to instability. The prominence of the IMU—a group bearing “Uzbekistan” in its name—has at times led to the perception that extremism and terrorism are specifically problems among Uzbeks, an example of prejudice. Since many ethnic Uzbeks live in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan as well, such bias risks fueling clashes between Uzbek communities and others.

Persecution and overreach targeting “unofficial” Islam not recognized by governments are also problems. In Uzbekistan, invoking the 1999 bombings, the Karimov government cracked down on religious figures and opposition party members, imprisoning thousands. In Kyrgyzstan, human rights groups have criticized harsh enforcement that criminalized mere possession of texts deemed extremist, leading to hundreds of convictions. In Tajikistan, President Emomali Rahmon has instructed citizens not to wear religious clothing associated with extremism or grow long beards, and has banned the wearing of veils in schools and minors praying in mosques.

Tajikistan’s President Emomali Rahmon speaking at the 64th UN General Assembly (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Drug problem

Drug trafficking is also a major problem in and around the Fergana Valley. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates that 80% of the world’s opium and heroin supply flows from Afghanistan to Asia and Europe along three main routes. Central Asia corresponds to the northern route, and in 2010, 15% of the opium and 20% of the heroin produced in Afghanistan is estimated to have transited Tajikistan. Drug addiction is widespread: in Osh, Kyrgyzstan, 1,400 drug addicts were registered as of 2012, but the actual number is thought to be about ten times higher, suggests one report. Many HIV infections due to injecting drug use have also been reported. Addicts may commit robberies to obtain drugs, worsening public security. Drugs thus pose a major challenge in Central Asia, intertwined with border issues, poverty, extremist activity, and government corruption. We consider each in turn.

First, the Fergana Valley’s areas of ambiguous borders facilitate trafficking. Even where borders are clearly demarcated, Central Asia’s mountainous terrain and uneven border enforcement make it difficult to fully prevent smuggling. And because many residents of the valley are low-income, they are more easily drawn into the drug trade.

Drugs also serve as a funding source for extremist groups. By the late 1990s, the IMU had become known as a drug trafficking enterprise whose business financed terrorist activity. Supporting this, major terrorist acts in Central Asia have occurred along established drug routes.

Moreover, governments that should be cracking down are implicated. Some law enforcement officials in Tajikistan are said to supervise drug sales, provide confiscated drugs to couriers, protect allied dealers, and arrest their competitors, according to reports (Note 9). In Kyrgyzstan, some border guards and police are involved, while in Tajikistan involvement allegedly reaches higher levels of government, according to one view. Income from the drug trade in Tajikistan is thought to be equivalent to about 30% of the country’s GDP.

In response to the drug problem, China, Russia, the European Union (EU), the United Nations, and others have provided cooperation and funding to Tajikistan, among others. The United States has spent nearly US$200 million on security assistance to Tajikistan since 2001. But much of the aid is administered by Tajikistan’s State Committee for National Security, and information on the flow of funds is not disclosed. Such support is thought to have deepened ties between the state and the drug trade. For example, stricter border controls can narrow trafficking routes, increasing opportunities for officials to solicit bribes, which in turn can systematize illegal trade.

Anti-drug advertisement in the Fergana Valley (Photo: Adam Jones / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Prospects

As we have seen, the Fergana Valley faces numerous challenges—its complex borders and historical background, as well as region-wide issues of poverty, politics, extremist groups, and drugs—which destabilize the area and likely contributed to the major conflicts described at the outset. Can these problems be resolved?

Politically, solutions might emerge if forces beyond the ruling elites can make their voices heard, but that will be difficult in the authoritarian systems entrenched in Central Asia. On drugs, policies may appear proactive on the surface, but particularly in Tajikistan the drug trade is said to be entrenched at the state level, making short-term solutions unlikely. As for extremist groups, there are concerns that activity in Central Asia could revive as people from the region who fought with extremist groups in Syria and Iraq have been returning in recent years.

On the other hand, investment in the valley appears to be picking up. In Uzbekistan, a Chinese firm aiming to build a smart-city (Note 10) complex is preparing a US$475 million investment. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, while still facing many issues to be resolved, are envisioning a railway through Fergana that connects to China. In Tajikistan, the United Nations is implementing economic assistance for youth and others with about US$2 million in funding from Russia, among similar initiatives.

The potential for conflict in the Fergana Valley will persist until the issues spanning the region—and Central Asia more broadly—are addressed. Investment in the valley is progressing, but more time is needed to judge whether it will actually alleviate poverty. We will continue to watch developments in Central Asia and the Fergana Valley.

Note 1: It is also argued that the Soviet Union deliberately divided the Fergana Valley among three republics to prevent its inhabitants from uniting against Moscow. Local power brokers lobbied the Soviet government to bring desirable areas under their jurisdiction. As these competing claims were reflected, Soviet-era borders around the Fergana Valley ended up with a complex outline dotted with multiple enclaves.

Note 2: The president was not harmed in the blast, but there were nearly 150 casualties, including 16 deaths, reported.

Note 3: In 2020 there were reports that landmines along the Uzbek-Tajik border had been cleared.

Note 4: When GNV addresses poverty, we usually adopt the ethical poverty line of US$7.40 per day, but since this article focuses on a region—the Fergana Valley—rather than a country, and because the CAREC INSTITUTE figures did not provide data under that threshold, we compare using the US$5.50 per day measure.

Note 5: In a 2014 announcement by the Russian government, there were 4.5 million migrant workers in Russia from former Soviet Central Asian states, and the number of irregular migrant workers was estimated at about 3.7 million.

Note 6: This event was closely tied to Kyrgyzstan’s internal north-south divide. Northerner Akayev favored fellow northerners, and southerners—including those from the Fergana Valley—were said to have been distanced from power, allegedly.

Note 7: Here, “small-scale conflicts” refers to disputes over the use of water or land that spark resident-on-resident clashes involving stone-throwing or property damage, prompting the deployment of border forces. Representatives then hold talks and reach a provisional ceasefire without resolving the root issues.

Note 8: A main domestic issue is unrest in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, outside the Fergana Valley but part of Tajikistan. The government had recently carried out a heavy-handed crackdown there, and in May 2022, a violent response by authorities to protests against the crackdown sparked riots that left dozens dead. There were also reports that Tajik media were instructed by authorities not to cover the events.

Note 9: Tajik authorities are said to focus enforcement on small-scale dealers to increase the number of enforcement “results,” thereby obscuring ties with larger traffickers cooperating with the state, according to reports.

Note 10: A smart city is an urban area that uses information and communication technologies (ICT) to improve service quality and welfare. The Uzbek government has been actively adopting ICT-based systems from China.

Writer: Seita Morimoto

Graphics: Mayuko Hanafusa

フェルガナ盆地という名前は世界史でしか聞いたことがありませんでしたが、これほどの問題を抱えているとは知りませんでした。特に衝撃的だったのは薬物問題で、取引量もさることながら政府が取引に関わっている可能性があることです。もしこれが真実であれば、ギャングまがいのことを国家がやっていることになると思います。また、薬物は健康被害だけでなく、過激派を助長したり経済的に負の影響をもたらしたりもするので、国家として百害あって一利なしの薬物取引から一刻も早く手を引くべきだと思います。