Cotton is arguably the most familiar material used in clothing such as T-shirts and sweatshirts. Globally, 26.9 million tons are consumed annually. The cotton from which it is made is produced mainly in India, China, and the United States; in 2017, these 3 countries accounted for about 62% of global production. In 2019, India’s output was the largest. Despite being the world’s largest producer, it is hard to say that its producers enjoy affluent lives; the majority live in poverty. What lies behind this? Let’s unpack the problems faced by India’s cotton farmers.

Cotton T-shirts on display in a store (Photo: PickPic [public domain])

目次

The cotton industry in India

First, let’s trace the history of cotton in India. Cotton production is thought to have begun around 6000 BCE in the Indus River delta (present-day Pakistan). Production in India also dates back to more than 5,000 years ago. Around 200 CE, cotton goods were exported from India as luxury items to surrounding regions such as China and Parthia, and from there further west to the Roman Empire.

Until the early 18th century, India was the world’s hub of cotton production, but thereafter cotton cultivation in the U.S. South, underpinned by slavery, also increased. From the late 18th century onward, as the Industrial Revolution advanced the cotton industry in Britain, Britain made its colony India export cotton as a raw material, while Britain produced cotton textiles. As British machine-woven cotton cloth flowed into India, India’s cotton weaving industry suffered a major blow. In the latter half of the 19th century, when the American Civil War broke out in what was then the leading producer, U.S. cotton, India’s cotton exports grew.

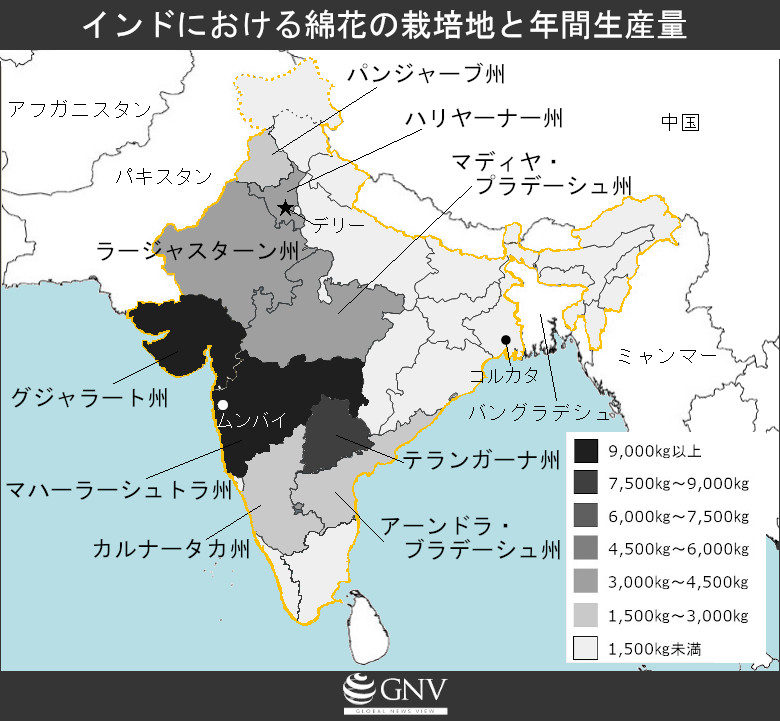

Today, cotton remains an important cash crop in India, and many people are involved in the textile industry. India has about 5.8 million cotton farmers, and a further 51 million, about 3.7% of the population, work in cotton-related industries such as yarn and fabric production. India also has the world’s largest area under cotton cultivation. The main cotton-growing areas are in 9 states in western India, grouped into the north, central, and south zones. According to 2018-19 statistics, Gujarat has the largest production in India, followed by Maharashtra and Telangana. These 3 states alone account for about 62% of India’s cotton output.

Created based on a map from Vemaps.com and materials (2018-19) from India’s Ministry of Textiles

The cotton produced is exported to more than 150 countries , with major trading partners including Bangladesh, China, and Pakistan. China and Bangladesh are the world’s No. 1 and 2 apparel exporters, and Pakistan also ranks in the global top 10 for textile exports. Cotton grown in India, as well as yarn and fabric made from it, are exported to these neighboring apparel-producing countries. Looking at global statistics, the largest cotton exporter is the United States, accounting for more than 1/3 of world exports.

Since 1970, cotton agriculture in India has begun shifting from traditional methods to technology-intensive ones. First came the use of “hybrid varieties” in cotton cultivation. Hybrid varieties are seeds developed by crossing different strains; they are expensive seeds that, when used with sufficient fertilizer and water, can increase yields. Because hybrid varieties do not occur naturally, seeds must be purchased every year to continue cultivation.

In 2002, the use of genetically modified (GM) seed was legalized, and a GM variety called Bt seed began to be cultivated in India. “Bt” stands for Bacillus thuringiensis, a bacterium that lives in soil. Because this bacterium can produce insecticidal proteins, inserting its genes into crops is believed to protect them from insect damage. Bt cotton derived from Bt seed was developed to control the pest known as the pink bollworm, which eats cotton buds, flowers, and seeds. As of 2020, more than 95% of India’s cotton area is planted with Bt cotton. The only GM seed approved for use in India is Bt cotton sold by Bayer (formerly Monsanto). At the time Bt seed was marketed, Monsanto was a U.S.-based multinational biochemicals company; in 2018 it was acquired by Germany’s Bayer. Bayer has since taken over and continues selling Bt seed to Indian seed companies and raw cotton producers.

Cotton bolls bursting open (Photo: S Aziz123/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Poverty challenges faced by cotton producers

Although cotton producers underpin the textile industry, many of them face serious poverty. An estimated 70–80% of cotton farmers cultivate only cotton, meaning many depend heavily on it for income. However, compared with other crops, cotton is not highly profitable. While the average annual income of Indian farmers is about 1,315 US dollars per 1 hectare (ha), the average for cotton farmers is about 995 US dollars per 1ha, a difference of about 300 US dollars. Furthermore, after deducting cotton cultivation costs, net profit is about 126 US dollars per year per 1ha. This shows that income from cotton is lower than from other crops and that cotton entails high cultivation costs.

Child labor is another serious poverty-driven problem. Although labor by those under 16 is illegal in India, an estimated 500,000 children work in cotton-related industries, the highest proportion of child labor of any sector in the country, according to reports. Cotton cultivation using hybrid varieties requires a great deal of labor, so children are often made to work in fields or in ginning, the process of separating fibers from seeds. Many children work 8–12 hours and still earn less than the minimum wage. Although the minimum daily wage is about 7 US dollars, there are confirmed cases where they are paid only about 2 US dollars, less than one-third of that. Many such children come from poor families. There are cases in which parents hand over children around age 10 to brokers; the children then work long hours on cotton farms and the parents receive the income directly.

Children working in a cotton field (Photo: François Zeller/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Suicides among cotton farmers are also a concern. Over the 10 years from 1995 to 2014, more than 270,000 cotton farmers are said to have taken their own lives. Ironically, pesticides used in cotton cultivation are sometimes used for suicide. In agriculture more broadly, suicide rates among farmers are higher than among the general population. The rate is especially high among smallholders, with debt traps frequently reported as a cause.

The “industrialization of agriculture,” i.e., cultivating with hybrid and GM seeds expected to help with higher yields and pest control, has not necessarily solved farmers’ poverty. On the contrary, it has become a factor that further burdens smallholders. This is because industrialization forces producers to farm while bearing greater risks. Even when expensive Bt seeds and fertilizers are purchased, yields swing with weather and rainfall in the absence of irrigation. In fact, whether irrigation is available is a major determinant of success with Bt cotton. Farmers with irrigation can access water reliably, leverage GM seeds to suppress pest outbreaks, harvest more cotton with less pesticide, and thereby reduce poverty. Incomes for farmers with irrigation are more than twice those without.

However, 65% of India’s cotton farmers lack irrigation and rely on rainfall. For such farmers, even when using GM seeds, yields ultimately depend on the weather. Because they have paid high upfront costs, a poor harvest increases the risk that costs exceed revenue and loans cannot be repaid. Some farmers even have to sell their homes or land to make payments. In this way, the “industrialization of agriculture” can push smallholders into poverty—and sometimes suicide.

Moreover, the use of GM seeds and pesticides intended to control pests has, in some cases, been linked to pests evolving greater resistance to chemicals. And when GM seeds raise yields per unit area, pests such as the pink bollworm that feed on cotton can also become more abundant. As a result, some farmers end up needing even more pesticide than before adopting GM seeds, increasing costs—a perverse outcome.

In addition, Bayer (formerly Monsanto), the seller of Bt seeds, has also sold proprietary agrochemicals and demanded royalty payments for seed use. India’s more than 40 seed companies have been required to pay about 10 US dollars per 450 g of seed as a product fee, plus royalties. After years of negotiations between the Indian government and the company, in 2018 the royalty was cut by 20% to 0.53 US dollars, followed by a further reduction in 2019 to half, 0.27 US dollars, and in March 2020 royalties were abolished altogether. However, because the price ceiling for farmers purchasing seeds remains in place, conditions for cotton farmers are unchanged, and it is said that the abolition of royalties will primarily benefit Indian seed companies rather than farmers as hoped。

Workers manually removing unwanted parts of cotton bolls (Photo: CSIRO/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 3.0])

Problems in cotton trading

Looking across the textile industry as a whole, trading companies and textile/apparel manufacturers high up the apparel supply chain wield major influence and capture most of the profits, while cotton’s participants sit at the very bottom with little clout. Only 10% of a garment’s retail price is returned to farmers as raw material costs.

Many farmers operate as contract growers, entering into agreements in which companies provide on credit the costly fertilizers, pesticides, hybrid varieties, and GM seeds needed for industrial agriculture and then purchase the harvested cotton. But companies set both the prices of inputs and the purchase price of the harvest, leaving farmers with little say in pricing and at a disadvantage in most cases. In India, laws to enforce minimum prices and minimum wages for farm labor, and their enforcement, are weak. Farmers’ weak bargaining position contributes to deeper poverty.

Where there is no contract farming, intermediaries or traders buy cotton from farmers, but there are problems of cotton being purchased at unfairly low prices, even below production costs. A primary cause is information asymmetry. Traders are well informed about international cotton prices, production forecasts, and global economic trends, while farmers know little about market prices or the world economy. When markets are stable this may not be critical, but cotton prices are highly volatile, leaving farmers with little market knowledge at an disadvantage.

Falling market prices are another challenge. The price of cotton, which was 3 US dollars per kilo in the 1960s, had fallen by 2014 to 1.73 US dollars per kilo—a 45% decline. One factor is the low price of U.S. cotton. Because the U.S. provides massive public subsidies to cotton producers, American farmers can sell cotton very cheaply while still receiving stable income via subsidies. To compete with the U.S., other producing countries have been forced to lower prices, but even then they cannot match the U.S., which has pushed down international cotton prices. The export share of U.S. cotton roughly 2x from 1995 to 2002 due to subsidies, but for smallholder cotton farmers in India and West Africa, the fall in international prices has become a matter of survival.

Workers standing on a mound of cotton bolls (Photo: Adam Cohn/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Price volatility driven by speculation

Not only price declines but also price volatility pose serious problems for farmers. Farmers must invest in seeds and fertilizers before production, and companies that lend to them also need to forecast post-harvest prices; without predictability, both are disadvantaged. In cotton, poor harvests due to weather or pest outbreaks can push prices up, as can increased demand from textiles and apparel, while prices can also fall. To mitigate this uncertainty, futures trading is used in cotton markets. Producers and buyers agree in advance on the price for a certain portion of future output; even if prices swing, the futures contract acts like insurance.

However, price movements are now also driven by factors beyond weather and supply–demand balances. Since the late 2000s, cotton futures have been treated like stocks, folded into speculation by investors and hedge funds, and traded repeatedly. In other words, third parties such as asset holders buy and sell cotton futures for profit, causing prices to fluctuate more widely and constantly for reasons unrelated to production on the ground. This makes price forecasting difficult. Futures trading has thus come to undermine its original aim of enabling “stable-price transactions.”

Outlook

As we have seen, although India is a leading cotton exporter and supports the global textile industry, many of its cotton producers cannot secure even a subsistence income due to a host of intertwined problems. How can we move toward solutions? There are some glimmers of hope.

Regarding the problems of industrial agriculture, there are research findings that suggest an effective alternative to GM seeds is to use varieties with shorter maturation that can be harvested before pests such as the pink bollworm proliferate.

To counter unfair intermediaries and powerful firms pushing down cotton prices, there is a move to promote Fairtrade. Cotton produced under standards that protect worker health and safety and prohibit GM seeds is certified as Fairtrade, and traded at or above a set minimum price. About 88% of Fairtrade cotton is from India; while still a small share of total production, volumes are gradually rising. Ethical fashion brands that ensure fair wages and safeguard traditional Indian craftsmanship are also increasing in India.

A spinning mill in India (Photo: lau rey/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Other necessary measures include limiting agricultural subsidies in high-income countries, strengthening regulations on cotton trading, and protecting smallholders from predatory intermediaries. Still, given the scale and complexity of the problems, these steps alone will not suffice. The issues described here are faced by the people who make the clothes we wear every day. The fact that we can buy on-trend clothing cheaply each season has hardship for producers in the background. As consumers, rethinking “what we buy” and acting accordingly may be the best solution.

Writer: Yuna Takatsuki

Graphics: Yumi Ariyoshi

綿花の裏側で発生している格差の仕組みがよくわかりました。

しかしこのような課題を解決するために、私たちが具体的にとれるアクションは何なのかまで追求する必要があると思います。

例えばフェアトレードはどうすれば増加するのか。

このような格差を多くの人が認識することも重要だが、さらには具体的な解決策を報道し、読者も考えるべきだと思いました。