To date, GNV has pointed out, based on its own analysis, a regional bias in international news coverage within Japan among major newspapers (Asahi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun). Overall, coverage of low-income countries such as Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and South Asia—the so-called “Global South” (※1)—is scarce, whereas coverage of the United States and other Western countries as well as East Asia is overwhelmingly abundant. This bias is no exception for election coverage.

Presidential and general elections are important events that not only change a country’s situation through a change of government and more, but that also bring to light domestic and external problems and clarify a country’s direction. Thus, election coverage can help us grasp international affairs, but when such coverage is heavily skewed, it becomes difficult for us to accurately understand the current state of certain countries. It is already clear that, compared with elections in the Global North where high-income countries are concentrated, election coverage in the Global South is overwhelmingly sparse; but among elections within the Global South, what differences exist? In this article, we explore that reality by focusing our analysis on election coverage in the Global South.

Scenes from elections in Nigeria (Photo: Commonwealth Secretariat / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Coverage of elections in the Global South

From GNV’s analysis to date, we know that international coverage in Japan is substantially skewed by region, and that low-income countries are hardly covered at all. Focusing on coverage amounts by region, reports on Asia account for 40–50%, North America for just under 30%, and Europe for just under 20%, whereas Africa and Latin America together amount to only about 5〜6% (※2), indicating a considerable bias.

As noted above, this tendency also appears in election coverage; as evidence, we introduce a past GNV article that analyzed global election coverage. In recent years within Japan, the country receiving the most election coverage was the United States, with more than four times that of France, which was in second place. Among the top 30 countries by population, North America (the United States) alone accounted for nearly half of all coverage, and when Europe and Asia were included, they made up more than 90% in total. The article also mentioned countries in the sample that received no election coverage at all, or almost none; all of these were in Africa and Latin America. In short, election coverage of the Global South in Japan is quite limited.

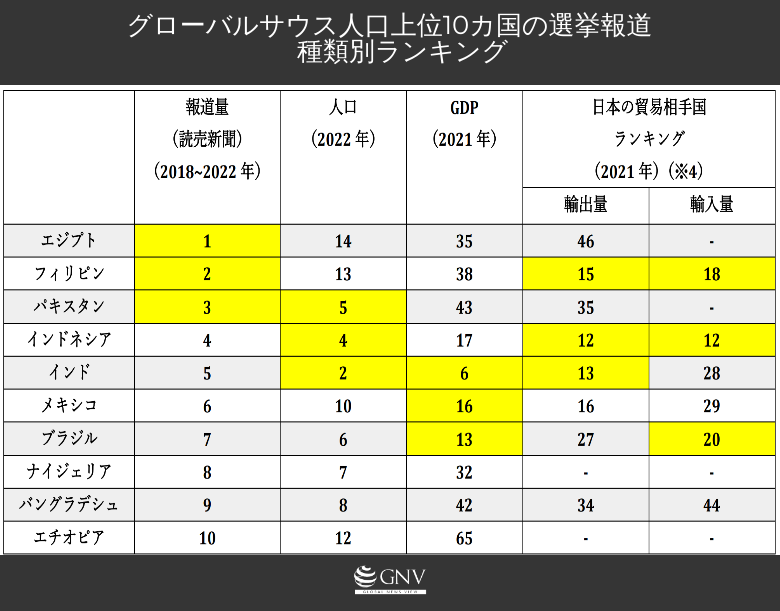

But what about within the Global South, where attention is limited? This time, focusing on the large countries within the Global South—namely the 10 most populous countries (※3)—we examined their election coverage, targeting the most recent presidential or general election (※4), using the Yomiuri Shimbun (※5).

First, we analyze the amount of coverage. We confirmed the paucity of election coverage in the Global South. To compare this amount with a country from the Global North, we conducted a similar survey for France, which held a presidential election in April 2022. Numerically, the average number of articles for the 10 Global South countries was 10, and the average total character count was 6,750; by contrast, articles on France numbered 45, with a total character count of 37,576. On average, there is more than a 5-fold difference in character count. Even when compared with Egypt, which was the most covered within the Global South, France’s coverage volume was about 2.4 times larger. This suggests that overall, election coverage of the Global South is indeed limited.

Looking at the graph above, we can also see that even within the Global South there is variation in the amount of election coverage. The country with the most was Egypt, followed by the Philippines and Pakistan; these 3 countries each exceeded 10,000 characters. By contrast, Ethiopia, with little coverage, had 1,958 characters and Bangladesh had 2,473, roughly a fivefold gap with the most-covered countries. In terms of article counts, Egypt had the most at 22, whereas Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Nigeria each had four, indicating differences in the scale of coverage.

Possible factor (1): Country size and ties with Japan

So what factors influence the amount of election coverage? First, the size of the country is a possibility. There are various ways to measure a country’s “size”; here, as examples, we look at its population and GDP (gross domestic product). Another factor may be the relationship with Japan. While news organizations are expected to provide broad coverage that captures the world as a whole, at their core they are still business models that seek profit. Countries that attract readers’ interest—that is, those with strong political, economic, or cultural ties to Japan—are likely to receive more coverage. Therefore, as one indicator of economic ties with Japan, we refer to the ranking of Japan’s trading partners. In addition, we use the physical distance from Japan as another indicator of the relationship with Japan.

The top three countries in each ranking among the 10 surveyed are shaded in yellow.

The first point to note is India, which ranks in the top 3 across the 3 indicators. India’s population exceeds 1.3 billion, the second largest in the world, and in terms of GDP it ranks sixth globally after the United States, China, Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Its ranking among Japan’s trading partners is also relatively high, meaning it combines population scale, economic scale, and strong ties with Japan. Yet its amount of election coverage ranks only fifth among the 10 Global South countries, which is not particularly high relative to its status. Its coverage volume is about one-3rd that of Egypt, the most covered. Conversely, looking at Egypt, it ranks low across all 3 indicators. In particular, its low GDP and low rank among Japan’s trading partners indicate small economic size and weak ties with Japan, and the physical distance from Japan is also large. Thus, these indicators are unlikely to explain Egypt’s high coverage.

Looking across the table as a whole, there is not necessarily a correlation between coverage volume and population, GDP , or trading-partner ranking. The Philippines, which is physically close and ranks high as a trading partner, has the second-highest coverage among the 10, suggesting country size and ties with Japan may have some influence. However, these alone do not explain the bias in coverage volume. Considering France from the Global North mentioned earlier, its population is about 65 million, whereas all 10 Global South countries exceed 100 million; in scale, the relationship with coverage is reversed. Furthermore, in terms of GDP and Japan’s trade relations, France trails India; in trade with Japan, it also trails Indonesia, and it is physically farther from Japan than both countries. This also suggests that the reasons above cannot account for the difference in coverage.

Possible factor (2): Presence of bureaus

Another possible factor is whether a news organization’s reporting hub is located in that country or its vicinity, which may be relevant. Each newspaper establishes a regional headquarters and bureaus in major cities—centered on countries and regions it deems important—as bases for international reporting, and dispatches correspondents. The figure below shows the 10 countries surveyed here and the locations of Yomiuri Shimbun’s overseas headquarters and bureaus.

Among these 10 countries, there were bureaus in only 4: Egypt, Indonesia, India, and Brazil. The election coverage volume for these four, in order, ranked 1st, 4th, 5th, and 7th among the 10. It would be simplistic to say a local bureau automatically means more coverage. Nonetheless, the distribution of bureaus is highly uneven: they are concentrated in Europe and East/Southeast/South Asia and the Americas, with only one bureau each in sub-Saharan Africa and South America, leaving correspondents to cover extremely wide areas. The Philippines (coverage rank 2) and Pakistan (3), for instance, are in regions where bureaus are concentrated and thus have relatively nearby bureaus. In contrast, Nigeria (8) and Ethiopia (10) have no nearby bureaus; they are presumably covered by the distant bureau in South Africa. While not definitive, having a reporting base in the country itself or its surrounding area appears to be one factor associated with comparatively higher election coverage.

Possible factor (3): What is reported

Additionally, the nature and content of events likely have a major impact on coverage volume. Even when we say “election,” the amount of coverage will vary depending on the significance and related developments. Let’s first look at coverage volumes by stage in the election process. The following graph classifies coverage into four types—before the election, during voting, election results, and post-election (※6)—and visualizes their amounts.

All countries had coverage before the election and of the results, but some had no coverage during voting or after the election, indicating variation in content and proportions. As a trend, pre-election coverage often reported on the issues at stake, leading candidates, opinion polls, and incidents of violence; coverage during voting often focused on the start of voting or demonstrations. Coverage of the results frequently reported the announced outcomes as well as detailed profiles of the winners, while post-election coverage discussed future policies and often included articles about opposition parties alleging ruling-party fraud. Looking across the graph, with Brazil being an exception, countries with more election coverage also had a higher proportion of pre-election coverage. The more a country attracts media attention, the more frequently it is reported on from before the election, resulting in a larger overall volume. In fact, Egypt—the most covered—was actively reported on from three months before the vote (※7), and the Philippines—the second most covered—from more than 5 months before; there was even reporting more than six months prior (outside our sample) (※8). Considering that most other countries’ coverage didn’t begin until less than 1 month before the vote, a pattern emerges in which highly covered countries are covered over a longer period and in greater detail.

Another perspective is that when there are salient issues to report, pre-election coverage increases, and total coverage rises as a result. Among the 10 countries surveyed, there were changes of government in three—the Philippines, Pakistan, and Brazil—and the graph shows a notable abundance of pre-election coverage in all three. A change of government has major implications for a country’s future and, by extension, for its region and the world, which likely drives greater attention. Brazil had active pre-election coverage, but after former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—who had been leading the polls—was imprisoned on bribery charges and his candidacy was annulled, there was no coverage at all for a full month leading up to election day (※9). This suggests that the competitiveness between candidates is also a key factor in attracting attention. Thus, “whether a change of government is at stake” and “how closely matched the candidates are” appear to be among the reasons for differences in coverage volume.

To further probe the realities of reporting, we also considered another content-related angle. One distinctive element that varied by country was the presence or absence of “violence,” such as attacks, terrorism, demonstrations, and detention of candidates. As examples, consider Egypt, which had the most coverage among the 10 countries surveyed, and Pakistan, which had the second most. In Egypt, a de facto dictatorship under President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi had continued for years; in this election, two powerful challengers to Sisi were detained or intimidated by his government and were eliminated from the race. In fact, the majority of pre-election reports primarily covered, or at least touched on, candidates being detained; counting these and articles about terrorism, there were 8 “violence”-related pieces out of 22.

In Pakistan, there were a series of large-scale terrorist attacks during the campaign period, including those that killed more than 100 people or in which candidates died. As a result, headlines frequently included words like “deaths” and “terror,” and “violence”-related articles accounted for 8 out of 18, nearly half. The tendency to report heavily on violence during election periods applied not only to these two countries. There were “violence”-related articles in three other countries: Brazil had 6 of 8, Nigeria 3 of 4, and Bangladesh 3 of 4. In other words, in elections accompanied by violent incidents, the majority of coverage tends to prioritize those incidents.

Scenes from elections in Pakistan (Photo: DFID – UK Department for International Development / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Misgivings about the election coverage

Given the analysis of coverage volume and content so far, what can we say? First, a point about coverage of Egypt. As mentioned, a de facto dictatorship under President Sisi has continued in Egypt; in this election, candidates were detained, intimidated, and excluded from the race by the Sisi regime. Numerous people have been imprisoned under trumped-up charges, the media are repressed, and Sisi’s de facto opponent was said to be a “stalking horse” fielded to give the appearance of an election. Ultimately, as the deadline approached, Musa Mostafa Musa, head of the opposition Ghad (Tomorrow) Party, filed his candidacy; however, he had expressed support for Sisi prior to announcing his run and stated outright that he entered the race to avoid a one-candidate vote of confidence (※10). Moreover, the Ghad Party held no seats in Egypt’s parliament (total 596), which is part of the context.

How did the Yomiuri Shimbun cover this election in Egypt? It clearly stated that it was a stalking-horse election, that candidates were being detained, and that an authoritarian regime had continued for years, and there were also reports detailing Egypt’s social conditions and problems. However, once the election began, such reporting disappeared, and frequent coverage focused only on opinion polls and a head-to-head between candidates. What matters here is the background of the election; we felt a sense of dissonance that a “sham election” was reported day after day as if it were a “normal election,” and that it was the most-covered within the Global South.

Even in countries with daily reporting, those with short articles tended to cover only which of the leading figures was ahead and the results of opinion polls. This was especially pronounced in Ethiopia. Of the four election reports on Ethiopia, three were under 400 characters, and they did not touch on the issues at stake or challenges. During the 2021 election period, Ethiopia was in the midst of a large-scale armed conflict between government forces and Tigrayan forces in the north. The conflict heavily involved clashes between government and anti-government forces, making this election highly significant in that context. However, when election reporting focuses only on numerical facts, it is difficult to convey the inner dynamics of the election.

Additionally, in countries where violence or terrorism occurred, we had the impression that the mere fact of such incidents was reported excessively. Reports on violence and terrorism centered on numbers of dead and injured; like opinion polls, these are numerical topics that are relatively easy for the media to report. Past GNV research has shown that news organizations tend to prioritize negative content. Of course, reporting on violence and terrorism should never be taken lightly, both from a humanitarian standpoint and for understanding the situation. However, simply reporting numerical facts and the perpetrators of violent incidents makes it hard to truly understand a country’s situation. To make reporting on violence and terrorism more meaningful, it is important to delve into the background behind the violence, as well as the issues at stake in the election and the country’s history.

Scenes from elections in India (Photo: joegoauk Last Namegoa / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Finally, a note on India. Long called the world’s largest democracy and the world’s 2nd most populous country, it has in recent years been said that its level of democracy has significantly declined. Its population and economy rank among the top globally, it has substantial trade relations with Japan, is relatively close geographically, and Japanese newspaper bureaus are stationed there. Nevertheless, coverage in the Yomiuri Shimbun was limited, with most articles being short. Could such reporting adequately convey India’s current situation, which many argue should be of global concern?

All 10 countries examined here are populous—and regional—powers. If election coverage does not deepen our understanding of key countries in the Global South, can we truly see the state of the world?

※1 There are various ways to define the Global South. For scholars and many nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), it generally refers to “countries in Africa, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and the Caribbean that the World Bank classifies as low- or middle-income,” and this is the definition adopted here. Other institutions such as the United Nations use it as a geographical categorization referring to Africa, Asia, and South America. As a new definition derived from the idea that the Global South also exists in the Northern Hemisphere, there is also a concept of a “global political community that recognizes multiple ‘Souths’ beyond geographic specificity and considers the conditions common to every ‘South.’”

※2 See the 2017 comprehensive monthly report, 2-1 Coverage by country (character count).

※3 The countries surveyed, in order of population size, were the 10 most populous: India (held a general election in May 2019), Indonesia (held a presidential election in April 2019), Pakistan (held a general election in July 2022), Brazil (held a presidential election in October 2018), Nigeria (held a presidential election in February 2019), Bangladesh (held a general election in December 2018), Mexico (held a presidential election in July 2018), Ethiopia (held a general election in June 2021), the Philippines (held a presidential election in May 2022), and Egypt (held a presidential election in March 2018). Note: Although China falls within the definition of the Global South, it was excluded from this survey because the one-party system under the Communist Party means there is no substantive electoral system.

※4 The database used was Yomiuri Shimbun’s Yomidas Rekishikan. Articles from six months before to one month after election day were included.

※5 The data referenced listed only the top 50 trading partners; for countries ranked below that, values are shown as “–”.

※6 Specifically, “before the election” refers to coverage up until voting begins; coverage on election day (or during the voting period) is “during voting”; coverage of the election results on the day they are confirmed and the following day is “election results”; and election-related articles published thereafter are classified as “post-election.”

※7 Yomiuri Shimbun, “Egypt: March presidential election; no strong challenger; Sisi’s re-election seen as certain,” January 10, 2018

※8 Yomiuri Shimbun, “Duterte’s daughter eager to run; Philippine presidential election; plan for father to become vice president,” July 25 2021

※9 Between “Former São Paulo mayor as ‘successor’,” published September 13, 2018, and “Brazil: far-right candidate backed by 60%; presidential election; eroding left through anti-poverty policies,” published October 22, 2018, there was no coverage of Brazil’s election.

※10 Yomiuri Shimbun, “Egyptian presidential election: Sisi’s advantage unchanged; one-on-one with small-party leader,” March 1, 2018; Yomiuri Shimbun, “Egyptian presidential election: ran to avoid a ‘vote of confidence’; Musa says ‘I’ll fight to the end’,” March 26, 2018

日本の外国の選挙報道のあり方については、欧米偏重でその次に東アジアやBRICSとなっていて、アフリカや中南米についての報道は皆無です。これは、日本がかつての欧米列強のような植民地を持たず、宗主国となっていないからです。また経済的な結びつきも少なく、貿易相手国としての比重も少なく報道機関としては選挙報道をしないのもうなずけます。しかし、今後、日本が世界に果たす役割を考えると、グローバルサウス国をはじめとする世界各国の報道も増やす必要があると思います。

グローバルサウスの選挙報道が少ない背景について、多角的か観点から調べ上げられていたのが印象的でした。

日本との結びつきや支局の存在だけでなく、当該選挙が持つ意味など様々な理由で報道量が抑えられているのだと勉強になりました。

クリティカルな結論が得られず、いささか残念だったかと思います。ぜひGNVとしてリベンジを期待しております!