Presidential and general elections are big events that come around only every few years. Whether a change of government occurs or not affects not only the country itself but also neighboring countries and sometimes the entire world. The impact extends not just at the national level but also to businesses and to us as individuals. Election coverage helps us understand such political situations in a country.

Voting in the 2007 French presidential election. Photo: Rama [ CC BY-SA 2.0 FR ]

From late last year into this year, the U.S., French, and South Korean presidential elections were heavily covered in newspapers and on television. Months before results were announced, the coverage delved into issues, the candidates’ backgrounds, policies and speeches, and opinion polls. However, not all of the hundreds of elections held around the world are reported on daily for months in advance. Just how much attention do elections in different countries actually receive?

With that in mind, we looked at the volume of coverage of the most recent presidential and general elections in the 30 most populous countries. (Note 1) This time, using the Yomiuri Shimbun’s Tokyo morning edition, we measured coverage going back six months from when the election results were finalized. (Note 2)

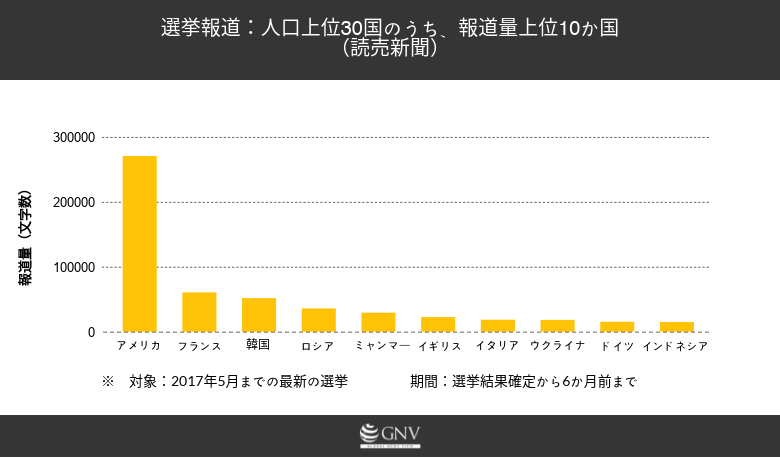

First, let’s see which countries’ elections were most reported. The graph below compares, by character count, the coverage of the 10 countries with the most election reporting among the 30.

Looking at the graph, it is clear that coverage of U.S. elections is far and away the greatest. Comparing the country with the most coverage, the United States, to the second, France, the difference is more than fourfold. Although this study counts coverage from six months before the election, these numbers alone do not capture all the reporting on the U.S. presidential race in Japan. In fact, reporting on the U.S. presidential election picks up as early as two years before voting, and in 2015 alone the volume reached 80,218 characters. Adding up the coverage from 2015 through the date the 2016 results were finalized yields 519,995 characters, roughly double the figure in the graph above. For most countries, if you look back even a month, there is almost no reporting on the election, but the U.S. presidential race was covered intensively nearly two years in advance.

Moreover, seven of these ten countries with the most election coverage also ranked in GNV’s previously introduced Top 10 countries featured in international news in 2015. In other words, these are countries that tend to be covered regularly. In addition, most are advanced economies; the only developing countries in the list are Myanmar and Indonesia. The tendency for wealthy countries to be reported on and poorer countries to be undercovered is reflected not only in international news overall but also in election coverage.

Looking more closely, the elections that received extensive coverage tended to be those in which major changes occurred. For example, in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Trump won and nativist sentiment surged. Riding that trend, attention focused on Le Pen in France’s 2017 presidential race. And in Myanmar’s 2015 general election and Indonesia’s 2014 general election, new forces broke the old order—historic events. Changes of government and major policy shifts brought about by elections have significant impacts not only on the country itself but also on its neighbors. Accordingly, such elections are relatively likely to be reported.

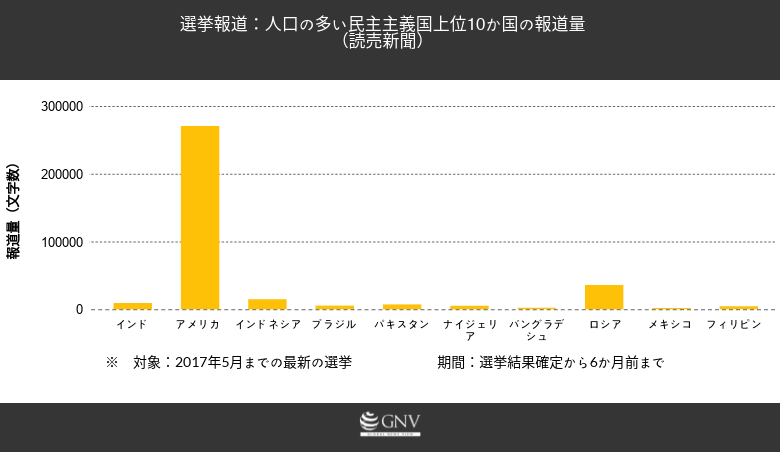

However, not every country that experienced a change of government received extensive election coverage. The next graph compares, in character counts, election reporting by country for the 10 most populous countries. Among them, seven—the United States, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Mexico, and the Philippines—saw the emergence of a new president or a change of government. Of these, only the United States and Indonesia exceeded 10,000 characters of coverage. Mexico had the least, with just 1,791 characters over the entire period. There were large differences in coverage by country, and we do not see a tendency for larger countries to be covered more. For more on differences in coverage among populous countries, see a previous GNV article.

Moreover, among the elections in these 10 countries, some were accompanied by major incidents or developments. Indonesia and Pakistan stand out as historically significant. In Indonesia’s 2014 general election, the country elected its first president who did not come from the military or the elite. In Pakistan, where civilian governments had repeatedly been toppled by military coups, the 2013 election produced the first consecutive democratic transfer of power. There were also countries where elections were held under threat. Nigeria’s 2015 presidential election saw repeated attacks and terrorism by the armed group Boko Haram; deemed unsafe to conduct the vote, it was postponed by six weeks from its original date. During Bangladesh’s 2014 general election, clashes broke out across the country; on election day about 20 people were killed and as many as 440 polling stations were closed. Despite such significant election-related events, coverage did not increase.

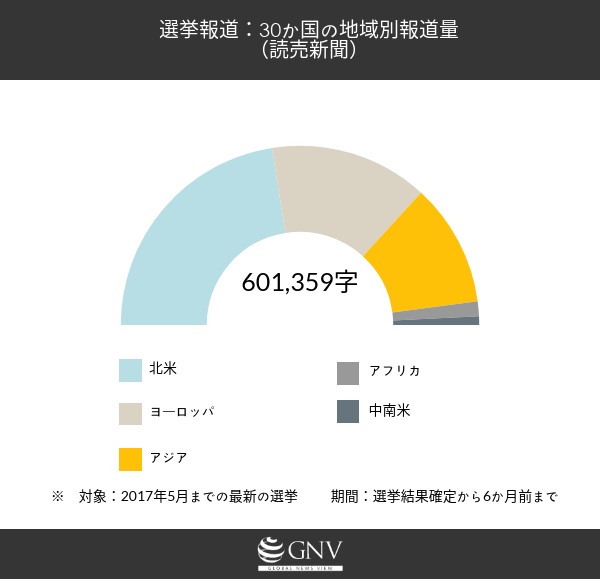

So far, we have analyzed coverage by country. Looking at the two graphs above, Western countries stand out. So what do the shares look like by region? The graph below shows election coverage for the 30 most populous countries broken down by region.

North America alone accounts for nearly half of the total coverage across the 30 countries. It is followed by Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The shares for North America, Europe, and Asia are quite large, whereas coverage of Africa and Latin America is scant. One point to note here is the number of countries in each region. Of the 30, North America consists of only one country (the United States), Europe has seven, Asia nine, Africa nine, and Latin America four. This underscores that countries in Africa and Latin America are less likely to be covered than those in other regions.

Let us therefore dig a bit deeper into election coverage in Africa and Latin America. Most strikingly, there was no coverage at all of the elections in Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Sudan. In other words, not only the circumstances of the elections but even the results and the fact that they were held were not reported. For Colombia, Argentina, South Africa, Kenya, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, reporting was limited to the fact that an election was taking place and its outcome, with little on the substance. Argentina’s 2015 presidential election saw a change of government, yet coverage totaled only 1,706 characters. In Colombia’s 2014 presidential election, despite the major issue of peace in the conflict, coverage came to just 564 characters. Unlike in other regions, election reporting in Africa and Latin America contained very little of the information that ought to be conveyed, such as candidates and key issues.

In this article we analyzed election coverage for the most populous countries. We found large differences in volume by country and by region. In particular, elections in Western countries were readily reported, while those in Africa and Latin America were rarely covered. It was especially striking that some highly populous countries received no coverage at all. Even among very populous, economically powerful states like Brazil and India, there were countries that drew little attention. Meanwhile, elections in Western advanced economies not included among the 30 most populous—such as the Netherlands (6,768 characters) and Canada (4,041 characters)—were relatively well covered. Whether there was a change of government or other political shift seems to have some effect on coverage volume, but this did not apply much to countries in underreported regions.

For countries that receive little coverage, there is concern that even if major political events occur in the future, they still will not be widely reported. Without an accumulation of background knowledge, it is difficult to catch up in understanding the issues. Elections should be regarded as a first step toward understanding a country’s politics; we hope to see reporting that takes the entire world into view and is more balanced.

Election campaigning in Nigeria (2015), Photo: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung/flickr [ CC BY-SA 2.0 ]

Notes

Note 1: Of the 30 countries, the non-democratic states of China, Thailand, and Vietnam, as well as Japan, which is not the subject of international news coverage, were excluded from the study. We traced back to the most recent elections in the 30 countries and analyzed them; the survey period spanned from the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s general election on November 28, 2011 to Iran’s presidential election on May 19, 2017.

Note 2: We counted, by country, the character counts of articles whose headlines contained a candidate’s name, a party name, the word “election,” or other election-related keywords.

Writer: Miho Horinouchi

Graphics: Miho Horinouchi

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks