How much can we really understand the world from the news we usually see? As described in an article previously published on GNV, as globalization advances and the borders between countries grow blurred, it has become difficult to insist that what happens on the other side of the planet has nothing to do with us. With the spread of the internet, we can now connect instantly with people all over the world in both business and daily life. This makes it all the more necessary to learn the state of the world through international reporting. At the same time, it is the information disseminated by the mass media that cultivates public interest. A world seen through a nation-centric lens often differs from the real world. As noted in GNV’s article that investigated and analyzed the state of Japan’s international reporting, Japanese international news coverage is biased. The regions covered tend to be those with strong ties to Japan, high international status, or the developed world. In its current skewed state, such reporting can hardly be said to convey the world as it is.

One way to see which parts of the world are prioritized—and which are not—is to look at correspondents. A correspondent is a special reporter assigned to a foreign bureau or headquarters who covers and reports on the region from that city as a base. Every day, correspondents around the world relay what they have covered, and editors decide daily whether to run those stories or not. Here, let’s look at international reporting in Japan from the perspective of these “correspondents.”

Placement of correspondents and volume of coverage by region

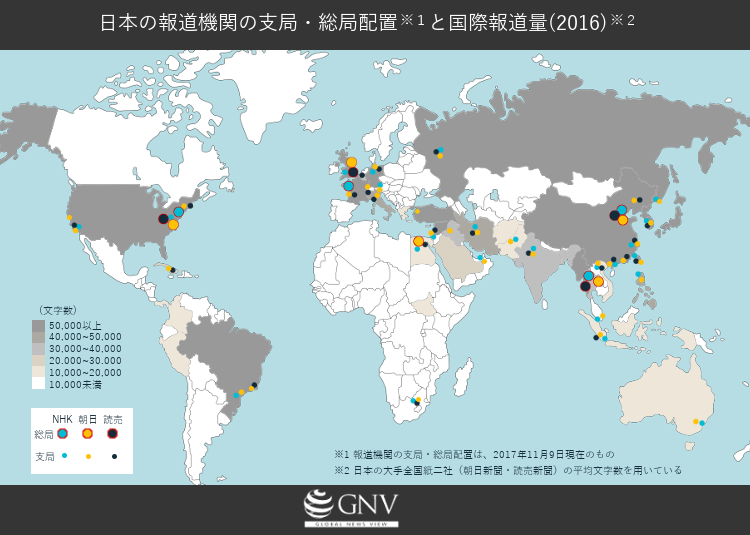

First, take a look at the map showing the locations of overseas bureaus with correspondents from two major Japanese newspapers (Asahi and Yomiuri) and NHK, along with the volume of coverage by region in 2016.

Volume of coverage by region and placement of overseas bureaus

As the figure shows, regions with many overseas bureaus such as Asia and Europe receive a lot of coverage, while Africa and Latin America are covered relatively little. Bureaus exist in developed countries and in regions with large trade volumes with Japan, but are scarce in poorer countries. In addition, over a six-month period on NHK’s program News Watch 9 in 2012, the only report from Africa was on Egypt, and the only report from Latin America was on Rio’s carnival, as was revealed by a certain study a study. Africa, which receives little coverage, consists of 55 countries—about a quarter of the world. Yet the realities of those countries are rarely reported. It is more accurate to say that there is little news because there is no bureau, rather than that there is no bureau because there is little news. Choosing not to place a bureau, from a long-term perspective, imposes a regional bias by deeming that “there is little in that country or region worthy of reporting.”

Reporting in regions with few correspondents

Advances in communications have made it possible to obtain real-time information from anywhere in the world, but a news organization would have little reason to exist if it relied only on such secondary information. What happens to reporting when foreign correspondents are not near the places they want to cover?

Each news organization’s overseas bureaus number only one in sub-Saharan Africa. The area that must be covered is extremely large, and in reality they are unable to gather information on most countries. Because a correspondent can only be in one place at a time, the areas they can report from are limited, and many stories inevitably go by the wayside. So what happens if a horrific incident occurs in this region? For example, if word comes of a massacre in a rural area of an African country, it is the correspondent at the overseas bureau who will go to cover it. Considering transportation, it could take several days to reach the scene. In reporting—where freshness is often the very value—taking time from the event to the broadcast is fatal; and on top of that, what if another important development occurs somewhere else? With so few correspondents, it is difficult to split them among multiple locations. As a result, the planned coverage of the initial country gets postponed, ending up inadequately covered or, in some cases, never covered at all.

It is also difficult to conduct long-term reporting in regions like Africa. Because there are so few correspondents, staying in one place for an extended period would neglect coverage elsewhere. This actually happened when former South African president Nelson Mandela fell ill and was in critical condition. Mandela’s stature was of immense international significance, and many journalists hurried to Africa—a place they normally do not visit—to cover the story. In effect, they were waiting for the news of Mandela’s death.

In anticipation of reporting the death of Mandela, a man revered around the world, countries dispatched not only reporters but many staff such as camera operators. Hotels in Johannesburg overflowed with media. However, contrary to the reporters’ expectations, Mandela kept the flame of life burning longer than they had predicted. They visited his hospital every day, yet nothing they wished to report occurred. The journalists’ stay became unexpectedly long. Unable to keep large crews in Africa indefinitely, some among the media harbored an improper hope. Their behavior was scorned by Mandela’s eldest daughter, Makaziwe, who likened them to “condors waiting for a lion to finish eating a buffalo.”

So does that mean regions without correspondents cannot be reported on? In such cases, news outlets often use wire services. A wire service is an organization that gathers far broader information than any single outlet can and supplies much of the media’s information. News organizations relay stories based on what they obtain from these agencies, but the information from wire services is, at best, bare facts and cannot convey the background narratives or relationships that one would ideally want to report. In the end, without on-the-ground reporting, you cannot obtain the information you seek.

Reporters are always chasing the news( NASA Goddard Space Flight Center/ flickr: (CC BY 2.0))

To know the world as it is

The placement of correspondents around the world is determined by factors such as relations with one’s own country, but the imbalance is so great that most of the world is barely visible in the news. It may not be wrong to vary the number of correspondents by region, but the status quo cannot be said to convey the world as it is. As noted at the outset, in today’s era where national borders have become extremely blurred, it is unwise to reject information by saying “it has nothing to do with us.” What is happening in the world now? To bring reporting closer to its proper form, correspondents have a very large role to play.

Writer: Yusuke Sugihara

Graphics: Hinako Hosokawa

海外に報道したい事があります。

多分、日本人の陰謀が明らかになります。

ワクチンについても、何か分かるかも知れません。