In the article “Five Misleading Words in International Reporting (Part 1),” we argued that terms such as “international contribution,” “pro-◯ country,” “civil war,” “developing countries,” and “fair trade” in Japan’s international reporting hinder understanding of the state of the world. As Part 1 pointed out, using such terms can transmit meanings inaccurately, or allow expressions that do not capture reality to become “common sense.” This is by no means a matter of semantics or an armchair issue. The misunderstandings these words cause can lead to real-world problems—and in some cases even involve danger.

This is the second installment. We will introduce the meanings of each term and, in gojūon (Japanese syllabary) order, look at how the media use them and what kinds of misunderstandings arise.

Kashmir, Srinagar (Photo: Adam Jones/Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 2.0])

目次

“Islam”

In many regions and countries around the world, organized religion goes beyond personal faith and exerts a major influence on society, politics, the economy, and lawmaking. In extreme cases, religion can become one axis of friction or conflict. Islam is no exception, and it is not uncommon for Islamic doctrine to be closely connected to believers’ living environments at various levels. Against this backdrop, there are numerous events, phenomena, and trends related to Islam that merit coverage. The pilgrimage to Mecca in Saudi Arabia, which draws some two million people each year, is one example. Trends in the relationship between politics and Islam are also an important angle in reporting. In addition, developments in Islamic finance in line with Islamic teachings, as well as conflicts and acts of violence, cannot be overlooked.

However, in Japan’s international reporting, coverage of Islam shows various biases and disconnects with reality, and is unbalanced. First, the imbalance in coverage volume by region stands out. A 2019 study of Asahi Shimbun’s reporting found that the country receiving the most coverage related to Islam was not a country with many Muslims, but the United States. Japanese media already report heavily on the United States, and that tendency is reflected in coverage related to Islam. Conversely, Indonesia, which has the world’s largest Muslim population, does not even appear in the top 10 for coverage related to Islam. As for content, reporting on the relationships among society, politics, the economy, and Islam is scarce, while the relationship between Islam and violence tends to be emphasized. For example, a study (2015) of Japan’s three major national dailies found that about half of Islam-related reporting (Asahi 58%, Mainichi 42%, Yomiuri 52%) involved violence; a similar trend was found in a 2019 study as well.

Under such reporting conditions, it is impossible to grasp the state of Islam in the world in a multifaceted and accurate way. Opinion polls in Japan show low levels of understanding of Islam and many people viewing it negatively, and the results likely have much to do with the biases described above.

Uzbekistan, Bukhara (Photo: javarman/Shutterstock.com)

“SDGs”

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): the 17 goals set by the United Nations in 2015 to be achieved by 2030, aimed at solving serious challenges facing humanity in areas such as the economy, education, health care, gender, and the environment. “Leave no one behind” is their slogan.

Some goals have seen a degree of progress, but for many it is hard to say the world is on track to achieve the SDGs. It is already clear that at this rate the SDGs will not be achieved by 2030. For example, regarding Goal 1, “No poverty,” research as of 2019 forecast that 500 million people will still be in extreme poverty by 2030 (Note 1). Most of them live in sub-Saharan Africa. Without solving global poverty, it will be difficult to achieve other goals such as health care and education, and comprehensive realization of the SDGs will be extremely difficult without ending extreme poverty. The Target under Goal 4 on education, to “ensure that all children (…) complete primary and secondary education,” required that by 2021 all children in the world be in school if it is to be met by 2030. However, at present one in five children worldwide are not attending school. A similar pattern is seen in environmental goals. For example, global carbon dioxide emissions are continuing to rise rather than fall. And the 20 targets set in 2010 to be achieved over the decade to protect biodiversity (the so-called “Aichi Targets”) were found, as of 2020, to have all been missed.

Japan’s media, albeit belatedly, have increasingly focused on the SDGs in step with government and society. However, in terms of the scale of the problems and awareness of them, coverage is far removed from reality. In five years of Yomiuri Shimbun coverage from 2014 to 2018, of 104 total SDG articles, only six focused on poverty. Even when poverty is covered, the focus often turns to Japan rather than sub-Saharan Africa, where the problem is overwhelmingly severe. For example, a short overview segment on Nippon TV titled “What are the SDGs?” said, “Poverty may sound like a problem of developing countries, but in fact one in seven children in Japan is in poverty…”—focusing solely on poverty within Japan without touching on extreme global poverty. The SDGs are also frequently reported as business opportunities for Japanese companies, or in the context of events such as the Tokyo Olympics and Expo 2025 Osaka. Such reporting far outweighs coverage of the global crisis that necessitated the SDGs in the first place and of the status of progress toward achieving them.

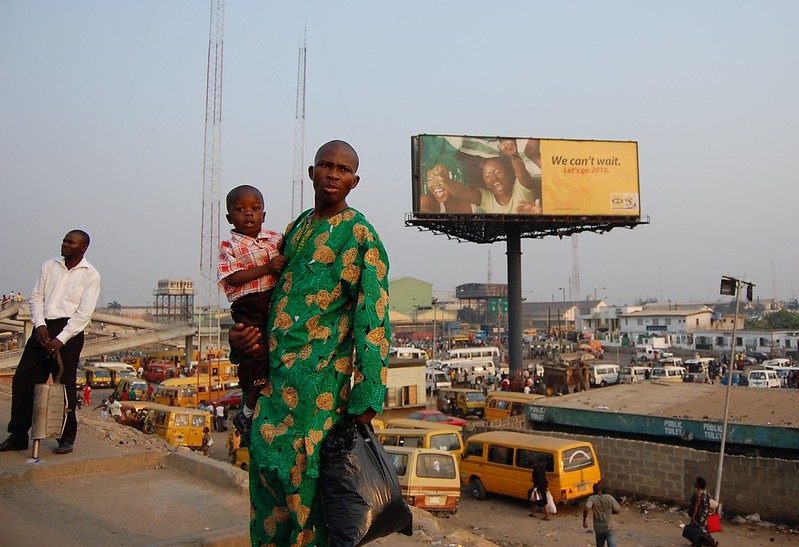

Nigeria, Lagos (Photo: William Muzi/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

“International community”

This term is frequently used by the media to denote global political trends. In 2019 alone, it appeared in 564 Asahi Shimbun articles, 644 Mainichi Shimbun articles, and 563 Yomiuri Shimbun articles (Note 2). The frequency suggests the meaning is shared by readers and has become “common sense.” Yet the contexts in which it is used are so broad that it is nearly impossible to pin down its meaning.

It is clear that the very definition of “international community” is vague. Definitions include “the countries of the world considered as a group or as acting together,” and “a phrase used especially by politicians and in newspapers to refer to all or some countries of the world or to regard the governments of those countries as a group” definitions. What emerges is that the “international community” refers not to the world’s people (and their public opinion) or transnational civil society organizations, but to national governments that hold power. But how many governments must coordinate before one can say an “international community” is at work? Does a majority in the UN General Assembly constitute a single “community”? Or can the gathering of the G20, where power and wealth are concentrated, or the G7 be called the “international community”? In reality, given governments’ divergent interests and tendencies to prioritize national interests, it is rare for them to cohere as a single body, taking positions or acting by consensus.

Using the term “international community” vaguely in the media risks creating the misunderstanding that a global consensus exists when it does not. For example, an Asahi Shimbun editorial (2018) on Saudi Arabia’s human rights issues stated, “Amid the retreat of U.S. leadership, the responsibility for defending the values of freedom and human rights must be borne by the international community as a whole.” But how many governments in the world (including the United States) actually respect freedom and human rights? And in AFP’s reporting (2020) on the Armenia–Azerbaijan conflict, it said “There are growing calls from the international community (…) for a ceasefire and the start of talks,” but how many governments actually issued such statements? It may be a convenient phrase for the media, but it does not necessarily reflect the reality of global solidarity.

UN Security Council. Open debate on “Women, Peace and Security” (Photo: UN Women/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

“Terrorism”

The term terrorism (“terror”) appears frequently in international reporting, but are we really capturing its meaning and current reality? There is no global consensus on the concept itself. Conflict parties and governments tend to craft definitions to suit themselves, so many different definitions exist. That said, many of them include three elements: an act of violence or threat of violence; targets being civilians or non-combatants; and the use of fear generated by the act to pursue political, economic, or religious goals (Note 3).

The image of “terrorism” that emerges through the media may be bombings or mass shootings in high-income Western countries far from conflict zones. This reflects the regional imbalance in terror-related coverage. For example, an analysis of international reporting in Japan’s three major national dailies (Asahi, Mainichi, Yomiuri) found that in 2015, 63% of terror-related coverage concerned incidents and countermeasures in Europe and North America. In reality, however, the scale of harm in the West is small compared with other regions. In terror incidents in 2015, deaths in the West accounted for about 6% of the global total, and for the period from 2002 (after the 9/11 attacks in the U.S.) to 2018, deaths from terrorism in the West amounted to only about 1% of the world total. Over this period, the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia together accounted for 93% of global terrorism deaths. Since 2015, deaths have been concentrated in Iraq, Syria, Nigeria, and Afghanistan, among others.

Related term: “war on terror.” This was a misnomer from the outset. “Terror” is not a conflict party or group but a method of violence; one cannot wage war on a method. The term was introduced by the U.S. government to justify wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere in the Middle East and Africa. The media around the world used it uncritically. Since 2008 even the U.S. government has stopped using it, yet Japanese newspapers still sometimes use it—without even placing it in quotation marks.

India, Mumbai. Memorial service for the 2008 coordinated terrorist attacks (Photo: Alosh Bennett/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

“Ethnicity”

The concept of “ethnicity” is difficult to define and cannot be neatly bundled into one category. Among several different definitions, representative ones include “a group sharing common customs, traditions, historical experiences, and, in some cases, geographic residence” definition. However, under any definition, the elements that constitute “ethnicity”—language, traditions, religion, and more—are diverse, and the concept itself is undeniably vague. Moreover, the fact that ethnicities have been formed through war, oppression, and power is one factor that complicates the concept. It is fluid, and it is no exaggeration to say that whether people belong to an ethnicity, to what degree they do so, and whether they ascribe others to one depends greatly on individual perceptions.

While it is a label often used to simplify people’s sense of belonging, it is also true that “ethnicity” exists to a greater or lesser degree as one facet of identity, and using the term in reporting is not inherently problematic. However, precisely because it is ambiguous, it must be used with care. Especially in contexts of armed conflict, labels such as “ethnic conflict” can be misleading. For example, a Yomiuri Shimbun editorial (2019) attempting to simplify the post–Cold War world claimed that “ethnic conflicts and religious antagonisms that were contained during the Cold War have erupted,” a representative example. Armed conflicts are extremely complex social phenomena. Even if identity-based antagonism such as “ethnicity” is one axis of a conflict, there are other axes—such as political and economic interests among those in power, and relationships with neighboring countries or other great powers. Summarizing conflicts with the word “ethnic conflict” risks creating the mistaken belief that interethnic hatred explains them.

Related term: “tribe.” As a negative legacy of the colonial era that evokes primitive or savage images, the term is in most cases harmful. Originally, “tribe” was distinguished from “ethnicity” as a smaller unit composed of clans, but in Japanese media it is still, puzzlingly, used in the same context as “ethnicity” to refer to large identity groups, especially in Africa. For example, Mainichi Shimbun used it in an article on South Sudan (2016), and Nikkei in an editorial looking back on the Rwandan genocide (2019) (Note 4), to refer to groups that could be called “ethnicities.”

Belgium, Brussels. Demonstration protesting the oppression of Kurds in Turkey (Photo: Jan Maximilian Gerlach/Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

We have introduced five terms that frequently appear in Japan’s international reporting but whose problematic usage hinders understanding of the world. In this set of five, many terms either have meanings in reporting that diverge from the realities being reported, or are so ambiguously defined that they fail to represent the situation accurately. The world is vast, and because readers and viewers have limited opportunities to see, feel, and experience events around the globe for themselves, international reporting bears a grave responsibility to convey the situation accurately. International reporting that avoids causing misunderstandings and promotes understanding of the world is urgently needed.

The article “Five Misleading Words in International Reporting (Part 1)” is here.

Note 1: “Extreme poverty” refers to living on US$1.90 or less per day, the poverty line defined by the World Bank. However, there is criticism that this line is set far too low, and that at least US$7.40 a day is necessary to meet basic needs. In other words, even if Goal 1 were achieved, it would by no means mean the problem of poverty had been solved. Moreover, the poverty line estimates do not factor in climate change—expected to greatly worsen poverty—or the impact of the novel coronavirus that hit the world in 2020, so the situation is likely to be even more severe.

Note 2: Nationwide editions. Includes morning and evening editions, domestic and international reporting.

Note 3: The definition in the 2004 report by the UN High-Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change reads: “Any action, in addition to actions already specified in the conventions on aspects of terrorism, the Geneva Conventions and Security Council resolution 1566 (2004), that is intended to cause death or serious bodily harm to civilians or non-combatants, when the purpose of such an act, by its nature or context, is to intimidate a population, or to compel a Government or an international organization to do or to abstain from doing any act.”

Note 4: Mainichi Shimbun: “Close-up 2016: New missions for the Self-Defense Forces, training opened; struggles over expanded use of weapons” (October 25, 2016). Nikkei: “[Editorial] Keep Rwanda’s ‘miracle’ going” (April 9, 2019).

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

特にSDGsについては、浅薄な議論やニュースしか報道されておらず、なぜか響きの良い言葉として濫用されていると感じていました。メディアにはもっと本質をついた報道を期待したいです。

「便利」な言葉を普段無意識に使ってしまっていることによって、世界の問題を正確に捉えられない原因になってしまうこと

を知り、自分が使う時やメディアで読む際に気を付けたいと思いました。

ニュースのみならず様々な場面で何気なく目にしている言葉ばかりだが、この記事を読んで、一つ一つの言葉を改めて考える必要があると感じた。表面上うける印象に流されずに、本質を見極められるような「メディアリテラシー」を身につけたい。

「SDGs」という言葉はよく使われていますが、達成するために何を行っているのかなどはほとんど聞いたことがないと感じていました。目標を立てるだけでなく、達成するための具体的な方針が必要だと記事を読んで実感しました。

言葉によってイメージが作られるという恐ろしさを改めて感じた。そしてSDGsに使われている写真の人物の背景にある言葉、”We can’t wait”はまさにその通り。

「国際社会から見た日本」や「イスラム教=怖い宗教」という単純化が日頃なされていると考えていたのでこの記事はまさに頭の中でモヤモヤとしていたことを具体化し言葉にしてくれていたと思う。中でも言及されている通り、国際社会と一概にいってもすべての国を指しているわけではないのは確か。普段例に上がっていることばを使いがちなメディア関係者は、やはり出来事の背景をきちんと調べてからどういう言葉が一番ふさわしいのか考えて発信してほしい。