On May 10, 2021, clashes between Israel and Hamas, which effectively controls the Gaza Strip in the Palestinian territories, broke out and continued until a cease-fire agreement on the 21st. The 11 days of fighting were widely reported around the world, not only in Japan. However, from the perspective of human life, many conflicts during the same period caused far more deaths than the Israel–Palestine conflict. Why, then, is this conflict reported so extensively? We explain the reasons while comparing the scale of conflicts and the volume of coverage.

Israel Police on the second day after the outbreak of fighting (Photo: Israel Police / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

目次

The scale of conflicts around the world

Where does the Israel–Palestine conflict stand in terms of the number of deaths compared to other conflicts worldwide? Using data from the research organization ACLED, which compiles details of all reported political violence and protest around the world, we compared the scale of each conflict in the first half of 2021 (Note 1).

Sorting conflicts in that period by number of deaths, the top 10 countries are Afghanistan, Yemen, Nigeria, Mexico, Syria, Myanmar, Ethiopia, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Somalia. In Afghanistan, which had the most deaths at 21,572, fighting between the government and the Taliban—opposed to the government and the U.S. forces whose full withdrawal was decided in 2021—remains intense. In Yemen, which had the second-highest number of deaths at 9,198, a multi-party armed conflict involving the Houthi rebels, the Saudi-led coalition, the government, and others has continued since 2014. In northeastern Nigeria, which had the third-highest number of deaths at 5,024, the government is fighting the insurgent group Boko Haram and an IS (Islamic State) affiliate, and deaths from acts of terrorism are frequent.

Meanwhile, what about the scale in Israel–Palestine? The number of deaths during the same period was 290, ranking 26th when sorted by deaths. This is one-sixth that of Somalia, which ranks 10th with 1,800 deaths. Even a single casualty is a tragedy, but compared with other conflicts occurring worldwide, Israel–Palestine is relatively small in scale.

How much is it reported?

So, during the same period, how much coverage did the Israel–Palestine conflict receive? How balanced are the scale of the conflict and the amount of coverage? For this article, we counted the number of articles on conflicts by country (Note 2) and graphed the results. First, using the top 10 countries with the highest death tolls as a baseline, we compared the amount of coverage; the graph is below.

As the graph shows, reporting on Afghanistan, which had the highest number of deaths, was carried out to some extent compared to the other 10 high-casualty conflicts, except Myanmar. However, Yemen, with the second-highest death toll, had little coverage, with only 13 articles. Nigeria, in third place, had just two articles. Among the countries with conflicts ranking in the top 10 by deaths, three had no coverage at all. Meanwhile, articles on the Israel–Palestine conflict, which has far fewer deaths than those 10 countries, totaled 83—second only to Myanmar, where a coup occurred in 2021 and conflict intensified. Despite the fact that the fighting itself lasted only 11 days, the number of articles far exceeded those on other ongoing conflicts and even on Afghanistan, which had the highest death toll.

To examine the relationship between countries with a large volume of coverage, their conflicts, and their death tolls, we created a graph listing the 10 most-reported countries (Note 3) and included the death tolls from those conflicts.

Looking at the two graphs together further shows that coverage of conflicts is not necessarily proportional to their death tolls. Of the 10 most-covered countries, only four—Myanmar, Afghanistan, Syria, and Yemen—also rank among the top 10 by deaths. There are reasons other than scale and human cost that draw attention to conflicts. For example, in Myanmar, many Japanese companies have entered the market, and deep economic ties are one reason for the attention. In addition, although there are relatively many articles on Afghanistan, most of them dealt with the withdrawal of U.S. forces rather than conditions inside Afghanistan. Against this backdrop, Israel–Palestine ranks second in volume of conflict coverage. As shown in the earlier graph, it ranks 26th by deaths, and the period of escalation was short; why, then, is it covered so much?

This excessive focus on Israel–Palestine is not unique to Japan. Many news organizations worldwide actively cover the Israel–Palestine conflict, leading to situations in which Israel–Palestine stories dominate headlines. Perhaps because of the sheer volume of coverage, attention has also turned to how the issue is reported. One example is the perspective that each outlet’s reporting favors either Israel or Palestine; such criticism has been made in the United States

, the United Kingdom, and Japan. GNV, however, deliberately sets aside the question of bias in content and instead asks why other conflicts that affect far more lives receive so little attention while the Israel–Palestine conflict attracts so much.

Media surrounding the Israeli prime minister and the U.S. secretary of state in 2013 (Photo: U.S. Embassy Jerusalem / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

The relationship between historical interest and media coverage

How is attention to global conflicts formed, and why do they come to be widely reported by Japanese media? Understanding this requires not only examining Japanese reporting but also broadly exploring the political interests (Note 4) of government officials and the surrounding political and economic elite. Both political and media interests are shaped by layers of history and by perceptions formed over many years among governments and the public. In general, news organizations tend to report from a self-centered national perspective that prioritizes national interests, and their coverage tends to be influenced by their own country’s political priorities. Japan is no exception to this national-interest-driven tendency. And when considering Japanese reporting on Israel–Palestine, we cannot ignore the political interests of Europe and the United States, because, as GNV has shown, Japanese media are heavily influenced by Western political and media priorities.

To explore the historical background behind the concentration of Western political interest on Israel–Palestine, we look back at the founding of Israel and its relationship with Western countries. After World War I, European powers divided and administered under mandate the area where present-day Israel and Palestine lie, and the United States, the United Kingdom, and France played major roles in Israel’s founding in 1948. Among them, the United States has a history of providing enormous military aid to Israel continuously since its founding. Furthermore, after Egypt and other neighboring countries made peace with Israel in 1979, the United States provided financial military aid to those countries as well. In the United Nations Security Council (hereafter, the Security Council), the United States has repeatedly exercised its veto to prevent Israel from becoming the target of criticism or economic sanctions; from 1972 to 2020 it did so at least 53 times.

Japan, which has a strong alliance and robust economic ties with the United States—a country with deep ties to Israel—is highly sensitive to U.S. moves. As a result, politicians and bureaucrats tend to align with Washington, and U.S. political priorities become Japan’s political priorities. In turn, news organizations deem issues of high interest in the United States to be important for Japan as well, and coverage increases. This can be cited as one reason for the high volume of reporting on the Israel–Palestine conflict. In addition, the Japanese government has long regarded itself as having its own interests at stake in Israel–Palestine. For example, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in the context of securing crude oil from the Middle East and addressing international terrorism, has positioned Israel–Palestine as “the core of the Middle East peace issue.” It has argued that issues surrounding this region are “the key to peace and stability in the Middle East.”

Behind the Ministry’s tendency to connect the Israel–Palestine conflict with crude oil lies an event roughly 50 years ago. The oil shock triggered by the Fourth Arab–Israeli War in 1973, which began when Syrian and Egyptian forces attacked Israel to recover territory, caused various disruptions in Japan and became deeply imprinted in the memories of the government and the public. As a result, a persistent perception has taken root that deterioration in Israel–Palestine could lead to spikes in oil prices or supply disruptions and in turn to turmoil in the Japanese economy.

Gaza after air strikes by Israel (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The Israel–Palestine conflict is deeply embedded in contemporary U.S. politics

As noted above, the abundance of Israel–Palestine coverage in Japan is rooted in the political priorities historically formed in the United States. This is not merely a matter of the past; it remains a highly important perspective in U.S. politics today. In 2020, the United States provided US$380 million in military aid to Israel. During the renewed fighting in May 2021, Washington also exercised its veto in the Security Council to prevent Israel from being placed at a disadvantage. Aside from historical ties, why does the United States attach such importance to the Israel–Palestine conflict?

One factor behind the strong U.S.–Israel bond is the strength of the pro-Israel Israel lobby (Note 5). The Israel lobby is a constellation of lobbying groups composed of people who support the Israeli government’s position, including some Jewish Americans and Evangelical Christians who believe that defending the holy city of Jerusalem is indispensable to fulfilling the New Testament. Their activities include making political donations to U.S. politicians who support Israel and working to influence policy and public opinion by lobbying the government, think tanks, academia, and the media alike. Among them, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) works to build an even stronger U.S.–Israel relationship and is known for exerting very strong influence on U.S. policy. Leveraging its broad network, it funds policies that benefit Israel, and since 2014 is said to have spent over $3 million annually on lobbying. Many politicians are themselves members, and top politicians and experts regularly have opportunities to attend its conferences, making it a powerful force in current U.S. policymaking.

The AIPAC Policy Conference held in Washington, D.C. in 2017 (Photo: Paul Kagame / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Meanwhile, although still relatively small in strength, pro-Palestinian forces such as Muslims and left-leaning political groups are also gaining influence in the United States. During the May 2021 fighting, large demonstrations were held as supporters of Palestine gathered in major cities across the country to condemn the grim reality of rising deaths from intense Israeli airstrikes. In this way, activism on both sides—not only those supporting Israel but also those supporting Palestine—is further heightening political interest in the Israel–Palestine conflict.

Given that the conflict affects many aspects of society—including domestic politics, public opinion, and education—U.S. media interest is high and coverage is abundant. In addition, there are times when the Israel lobby attempts to influence coverage directly. For example, they mount letter-writing and social media campaigns, protests, and boycotts against outlets that report content critical of Israeli policies. News organizations may also engage in coverage that caters to the Israel lobby, which wields immense influence in politics and business, thereby benefiting Israel. Such dynamics are not limited to the United States; they also occur in the United Kingdom and Canada, where pro-Israel lobbying groups are said to exert strong influence.

Moreover, Jerusalem, which Israel claims as its capital, is a holy city in Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. The Israel–Palestine conflict therefore holds important meaning for these religions as well. The United States has many adherents of each faith; as of 2020 they together account for about 67% of the population. In terms of non-Christian religions in the United States, Jews and Muslims are the two largest groups. Because this conflict involves all three religions, many ordinary citizens feel personally invested in it. If the conflict intensifies, it could also lead to friction among believers not only in the United States but elsewhere in the world, potentially drawing even more global attention. Thus, the perspective of America’s three major religions can be one reason for the current U.S. interest in the Israel–Palestine conflict.

Beyond religion, there are other factors that make readers and viewers empathize with those covered in the news. Israel belongs to the group of high-income countries with living standards similar to the United States, and it is, at least formally, a democracy. In terms of security, many share the view that both countries confront Iran and extremist Islamist organizations. For these reasons, it is easier to elicit empathy among the U.S. government and public, which in turn increases the prominence of coverage.

Pro-Palestinian demonstrators in Montreal, Canada (Photo: Heri Rakotomalala / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Factors drawing attention in Japan today

What, then, are the reasons why the Israel–Palestine conflict continues to attract attention and receive substantial coverage in Japan? One is the continuing influence of U.S. priorities described above. But there are also Japan-specific factors. As noted earlier, the Japanese government has long paid particular attention to Israel–Palestine in relation to crude oil. The media have accordingly treated Israel–Palestine as important. The government’s perception that developments in Israel–Palestine are closely tied to Japan’s energy resources has not changed, and this remains a major reason why coverage continues to concentrate on Israel–Palestine.

However, there is a mismatch between this government perception and the reality on the ground. Although there are no commercial oil fields in Israel–Palestine, the Japanese government worries that if oil-exporting countries are drawn into the Israel–Palestine conflict, oil supplies will be disrupted. In practice, such a situation has not occurred for more than 40 years, and there are cases such as Egypt’s peace agreement in the 1970s or the United Arab Emirates’ normalization of relations. When fighting does break out between Israel and Palestine, neighboring countries sometimes mediate, making prolonged wars less likely. In fact, when the conflict escalated in 2021, there was no fluctuation in oil prices. Even in Israel’s stock market, recent escalations in the Israel–Palestine conflict have hardly moved prices. In other words, it has become common to view clashes between Israel and Palestine as localized and short-lived even when they occur. Explanatory articles that point out the abundance of Israel–Palestine coverage in U.S. media rarely cite impacts on crude oil supply as a reason.

Yomiuri Shimbun Online report (Photo: Akane Kusaba)

By contrast, the Yemen conflict, which neither the Japanese government nor media can be said to focus on, may have a greater potential to affect Japan’s oil supply. This is because the Yemen conflict directly involves more major oil-producing countries. For example, in March 2021, when the Houthi rebels backed by Iran attacked two oil facilities in Saudi Arabia, crude prices rose 14% the next day. In this way, there are conflicts other than Israel–Palestine that can affect oil supply and prices, yet Japan’s government and media continue to emphasize the impact of the Israel–Palestine conflict on oil and, as in the past, treat it as an important conflict that demands constant attention.

Another factor behind the abundance of Israel–Palestine coverage in Japan is that Israel, like Japan, is a high-income country. Japanese media have a tendency to prioritize topics related to high-income countries, so they may be inclined to cover developments in Israel, whose living standards are similar to those of the United States. In trade and business, there is also strong interest from the Japanese government and companies in Israel’s strengths in IT and security technologies.

Furthermore, the fact that the holy city of Jerusalem is involved in the Israel–Palestine conflict has, albeit slightly, influenced Japanese coverage as well. Although the number of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in Japan is small, there is an aspect of seeing it as an issue connected to other countries and regions.

Jerusalem, the holy city of three religions (Photo: 696188 [Pixabay License])

Reported because it has long been reported?

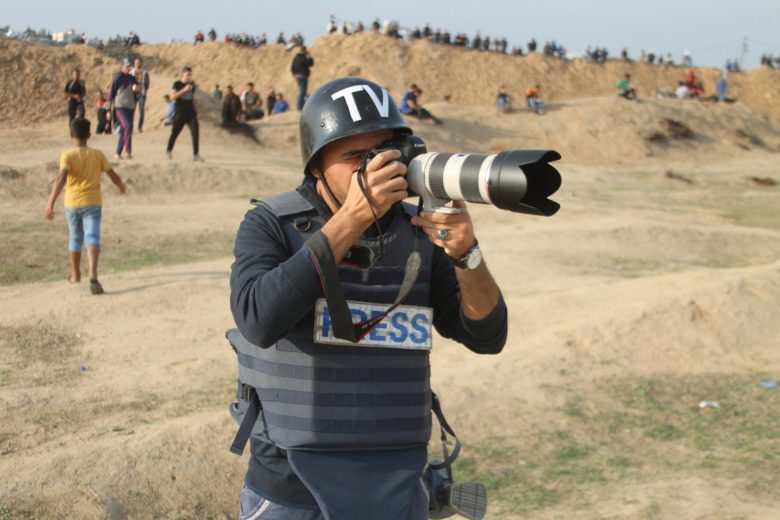

Current reporting cannot be separated from past reporting. One can say that the Israel–Palestine issue has been reported on for so long that an infrastructure for coverage exists, making it easier to continue covering it around the world today. As explained above, countries have historical and national-interest reasons for paying attention to the Israel–Palestine conflict. Consequently, without questioning it, media worldwide regard it as a major topic and believe it should continue to be prioritized. One manifestation of this ease of coverage is the placement of bureaus that enable ongoing newsgathering. Japan’s major media have bureaus in Jerusalem, creating a system that facilitates reporting.

Responding to the strong interest from global media, the Israeli government also invests in media relations. For example, by providing information and footage to foreign media, it becomes possible for overseas bureaus to report the latest developments from Israel’s point of view. Israel’s capacity to disseminate information and the speed of transmission thus also help drive media coverage of Israel–Palestine.

Moreover, because it has long been treated as important, studying its history has also been encouraged. The Israel–Palestine conflict appears prominently in history textbooks and is studied in detail over a relatively long period. For example, in one Japanese textbook (Note 6), all four Arab–Israeli wars as well as the founding of Israel after World War II are discussed, and content related to the Israel–Palestine conflict accounts for about 16% of the descriptions of wars and armed conflicts after World War II. Readers and viewers thus have a base of knowledge about the Israel–Palestine conflict. For news organizations, issues for which they can expect a certain level of understanding and interest are also easier to cover.

By contrast, there are conflicts such as the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo which, despite being among the largest in the world, are absent from textbooks and rarely covered. Because so little information is provided on such conflicts, they do not take root in the public’s knowledge and have long been deprioritized. As a result, they are deemed to have low news value, bureaus are not set up nearby, and the information available to readers and viewers becomes even thinner—creating a reverse cycle to that of Israel–Palestine.

As we have seen, a cycle can arise in which something continues to be reported “because it has long been reported” and “because it has long been studied,” as in the case of the Israel–Palestine conflict. At the same time, many other conflicts suffer from a lack of knowledge leading to indifference, resulting in little coverage and even less information.

Reporting in the Gaza Strip (Photo: Reporting in the Gaza Strip (hosny_salah [Pixabay License]))

Up to this point, we have explored why Israel–Palestine receives overwhelmingly more attention than other conflicts and why it is reported in Japan. Measuring scale by death toll does not allow us to view global events completely objectively, and news organizations surely use criteria other than scale when determining how much to cover. Even so, the current value judgments in reporting give far too little weight to the importance of human life. Furthermore, as the issue of crude oil supply shows, even when reporting from the perspective of Japan’s national interest, there is a gap between perceptions and reality. It is important to reexamine coverage biased toward national interest and high-income countries and to communicate in ways that enable readers and viewers to see the realities of the world’s conflicts from a broader perspective.

Note 1: Because of delays in data release, the data cover January 1 to June 25, 2021.

Note 2: Over the six months from January 1 to June 30, 2021, among international news stories in the morning and evening editions of Yomiuri Shimbun, we counted articles related to armed conflict. For the search, we looked up country names and then extracted those related to armed conflict.

Note 3: From among countries with at least 50 deaths during the period, we extracted the 10 with the most coverage.

Note 4: Although “political interest” is sometimes used to mean the public’s interest in politics, here it refers to topics considered important among forces within and around the government.

Note 5: Lobbying refers to efforts by companies, industry groups, civic organizations, etc., to influence policy and political decisions in their favor by approaching politicians outside the legislature.

Note 6: The textbook “World history and international reporting: Can we break the vicious cycle?” references “Detailed World History B / Yamakawa Publishing.”

Writer: Akane Kusaba

Graphics: Minami Ono

なんとなくよく報道されているなと感じていたイスラエル・パレスチナ紛争について、データを用いて他の紛争との比較を示し、なぜこのような報道がされるのかについて詳しく考察されていて、とても考えさせられる記事でした。

紛争によって報道量にここまで大きな格差があることに驚きました。とても興味深い記事でした!

死者数と記事数のグラフはかなりインパクトがあった。日本国内のニュースは死者数や被害の規模が優先順位に大きく関連するような印象を受けるが、国外となると物差しが変わってしまう。ではどういったニュースの取捨選択が良いのかと聞かれると難しいが、大手で報道されていることだけが全てだと思わず、広くアンテナを張っておきたいと感じた。