The role of the news media is to “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” This is a famous quote passed down since the 19th century and still used mainly within the journalism industry in Europe and the United States today. In other words, the media’s role is to speak for the voiceless and the vulnerable, protect them from harm and exploitation by those with power, and monitor, expose, and deter abuses of power and wrongdoing by the state and the wealthy.

But can we really say that the media in “democratic countries,” where freedom of the press should be guaranteed, are fulfilling this original role? State authorities and corporations can hide information detrimental to themselves. As a result, wrongdoing tends to occur within governments and companies; sometimes people inside these organizations who discover such misconduct become whistleblowers. News outlets and organizations such as WikiLeaks that receive leaked information from whistleblowers then transmit it to the public. This mechanism can be seen as a kind of safeguard to uphold democracy.

However, state power sometimes tries by every means to prevent such leaks from escaping or being published. A prime example is WikiLeaks and its founder Julian Assange, who, as of September 29, 2022, continue to face extraordinary persecution from the United States and the United Kingdom.

Moreover, if the news outlets that receive leaks are not interested in such issues, the “truth” will remain unknown to the public. In reality, even for leaks dealing with national security and human rights, or leaks about transactions by tycoons that appear to be improper, news organizations’ interest remains low.

This article explores leaks in international reporting and the challenges surrounding them.

WikiLeaks’ Assange delivering a remote speech from his place of asylum, the Ecuadorian Embassy in London (2014) (Photo: WorldCloudNews / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0] )

目次

Truths that aren’t hidden, truths that are

Looking at international coverage by Japanese news organizations, interest in the world is low to begin with, and, as GNV has pointed out, there is extremely little reporting on low-income countries, where the “afflicted” are concentrated. In international reporting, coverage overwhelmingly concerns the “comfortable”—that is, elites with power and wealth and high-income countries—and it tends to report from an elite perspective.

On armed conflicts, Japanese news outlets give wall-to-wall coverage to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a matter of high concern to high-income-country governments, but they hardly ever mention the Saudi-led coalition’s invasion of Yemen or the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which have caused casualties many times greater by comparison. When the United States, following the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan, seized all the assets of the country’s central bank and unilaterally declared that half would be used for the United States, Japanese outlets reported it as if it were part of U.S. humanitarian aid, in line with U.S. government propaganda.

They also lavishly cover topics related to the British royal family, which built the foundations of the former British Empire—such as individual marriages and deaths—as if they were entertainment, yet scarcely cover the violence and exploitation carried out under the monarchy or the undemocratic political system that persists today. Nor can their concern be called high for the world’s greatest public health challenges—malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis—or for the greatest environmental problem in human history, climate change. Information on these issues is already well established in some quarters, and news organizations are aware of it, yet they choose not to report it.

Meanwhile, where power and wealth concentrate, truths often remain hidden from the media under the cloak of that power and wealth. For the media to “afflict the comfortable,” they must bring to light truths that elites try to conceal. Leaks from the inside help make that possible.

A Canadian politician on the day of their election victory, surrounded by journalists (Photo: Olivia Chow / Flickr [CC BY 2.0] )

Leaks by governments

The relationship between leaks and journalism is not limited to state-level classified disclosures; it is far more familiar and routine, and it is no exaggeration to say journalism cannot function without leaks. In democracies, most leaks about government do not come from high-minded whistleblowers who witnessed wrongdoing; rather, they are authorized and provided by politicians or insiders within relevant ministries and departments. The motives behind such leaks vary. One is that politicians and officials hand internal information to journalists as ongoing “feed” to deflect critical coverage of themselves.

There are also aims that more directly shape policy. Leaks can be used to steer coverage of an issue in a direction favorable to the government’s position. For example, to pave the way for war against Iraq in 2003, the U.S. government asserted, starting in 2002, the falsehood that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction. As part of this, officials leaked incorrect information to the media that Iraq was seeking special aluminum tubes for uranium enrichment, attempting to spread disinformation through press coverage. Beyond that, governments sometimes test public reaction by partially leaking information about policies under consideration.

By orchestrating leaks strategically in this way, governments can use the power of the press to create an information environment favorable to themselves. If news organizations rely too heavily on leaks, they risk cozying up to officials and becoming “pets” of power, rather than the “watchdogs” that protect the public from it.

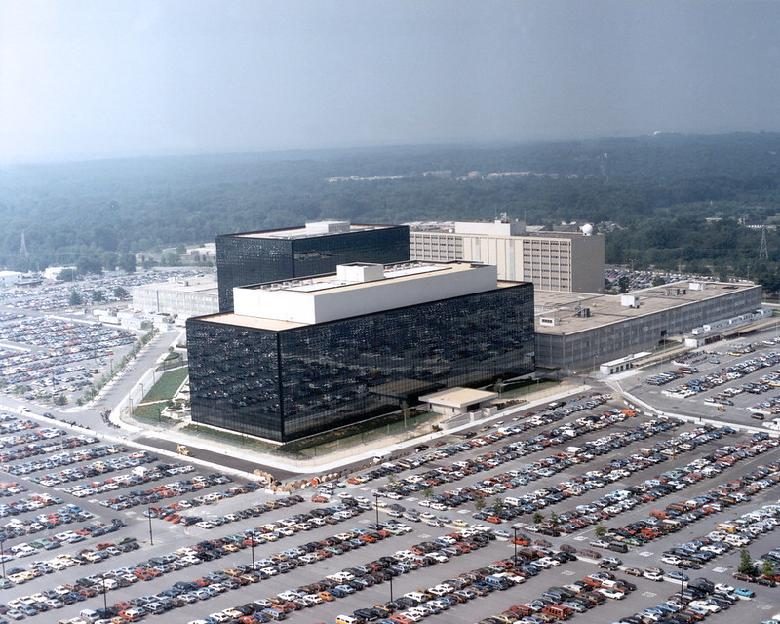

Headquarters of the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) (Photo: Fort George G. Meade Public Affairs Office / Flickr [CC BY 2.0] )

There are also times when governments allow leaks to pass without cracking down. Some argue that this gives the public reassurance that the truth will eventually come out, thereby increasing trust in government over the long term. However, governments cannot always control leaks at will. Leaks from officials are often used as weapons in internal conflicts within government or among politicians. For example, factions opposed to a policy under consideration within a ruling party or ministry may leak information unfavorable to its adoption to stoke public opposition. During election campaigns, politicians or their teams may leak damaging information about rivals to the media. Such cases have been seen in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Spain.

Leaks by whistleblowers

There are also rarer cases in which whistleblowers leak information to the media about wrongdoing or improper conduct within organizations. The content ranges widely, including national security, diplomacy, domestic and foreign intelligence activities, acts of repression, and political or economic corruption. In many cases, making information public through such leaks has led to major changes such as changes of government or revisions of law.

On national security, one example is the 1986 leak by a technician working inside Israel’s nuclear research facility, which revealed that the Israeli government possessed nuclear weapons. As for U.S. military actions, numerous disclosures have exposed them. For example, in 1971, internal reports that included inconvenient facts the U.S. government had hidden about the Vietnam War were leaked to the New York Times and the Washington Post—the so-called Pentagon Papers. In addition, in 2010, government documents on military operations—including acts suspected to be war crimes—in Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003) were leaked in large quantities through WikiLeaks War Diaries.

Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers, after testifying in court (1973) (Photo: manhhai / Flickr [CC BY 2.0] )

In diplomacy, the release of hundreds of thousands of U.S. diplomatic cables through WikiLeaks and other news organizations is famous. Many cables from Saudi Arabia and Iran have also been leaked. During meetings on Greece’s 2015 economic crisis, the European Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and Germany are said to have used their advantageous positions to apply undue pressure on Greece and force a solution upon it. Greece’s then-finance minister leaked and released a recording of events.

There have also been many leaks about U.S. intelligence activities and acts of repression. For example, disclosures revealed that under the program known as COINTELPRO (COINTELPRO), carried out by the FBI from 1956 to 1971, the bureau repeatedly infiltrated various domestic political organizations, conducted illegal surveillance and break-ins into offices, and carried out assassinations, among other acts—facts made public through a leak. In recent years, whistleblowers and WikiLeaks have revealed that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and National Security Agency (NSA), as well as the United Kingdom’s Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), have engaged in large-scale surveillance in violation of the law.

Leaks exposing political and economic corruption are even more numerous. In the Watergate scandal—a historic U.S. political scandal that led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon—leaks to the media were a key factor. In recent years, large-scale leaks through the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), supported by the cooperation of numerous outlets, have had major impact worldwide. The standouts include the Panama Papers (2016), Paradise Papers (2017), and Pandora Papers (2021), which exposed vast numbers of financial transactions in tax havens. These leaks led to suspicions of wrongdoing by some heads of state and, in some cases, to resignations, election defeats, or impeachment. The prime minister of Iceland, named in the Panama Papers, was forced to resign, and Pakistan’s prime minister was removed by the Supreme Court. In the case of the Pandora Papers, the Czech prime minister lost re-election and Chile’s president was impeached.

There are also multiple cases not involving ICIJ in which leaks led to the downfall of national leaders. In Malaysia, following a massive corruption scandal inside and outside the then-government, the former prime minister lost re-election in 2018, was indicted, and was convicted in 2020—but this corruption scandal came to light in part because of a leak. In South Africa, a scandal that grew out of the leaks resulted in the former president’s resignation in 2018, and, as of September 29, 2022, he remains on trial for corruption charges. In Brazil, which was approaching a general election, the incumbent president was predicted to lose; behind this were leaks related to corruption issues (as of September 29, 2022).

Former South African President Jacob Zuma and Saudi Arabia’s King Salman bin Abdulaziz (2016) (Photo: GovernmentZA / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0] )

Leaks beyond politics

It is not only state power that can be shaken by leaks. The bulk of the financial transactions revealed in several ICIJ investigations concern private individuals and companies. These investigations have brought to light issues such as the tax haven problem and large-scale cross-border tax evasion and avoidance. Leaks to other media have also exposed tax avoidance by billionaires who top rich lists. There have also been leaks that led to the collapse of Iceland’s largest bank (at the time, 2008) incident, and leaks revealing tax evasion in European soccer Football Leaks.

What leaks reveal is not limited to tax evasion and tax avoidance. In 1996, media disclosures made clear that the tobacco industry knew about tobacco’s addictiveness while publicly denying it, attracting great attention at the time and later being made into a film. There have also been leaks about a major multinational trading company from the Netherlands (now Singapore) that was held responsible for the 2006 illegal dumping of toxic waste in Côte d’Ivoire that caused many deaths, and leaks in 2017—amid attention to large-scale human rights abuses by the Myanmar military—about donations by a Japanese sake company to that military.

Even international organizations are not immune from whistleblower leaks. In war-torn Syria, the government was suspected of using chemical weapons in 2018, and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) reached the same conclusion. However, evidence submitted by two experts involved in the investigation contradicted that conclusion and claimed chemical weapons were not used. Their evidence and views were not included in the final report, but whistleblowers leaked them to the media, revealing that the OPCW had suppressed evidence. Some whistleblowers claim this was due to pressure from the U.S. government.

There have also been scandals revealed by information provided by whistleblowers within non-governmental organizations (NGOs). In Haiti, devastated by the 2010 earthquake, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) undertook a large aid project including housing construction. However, according to a 2015 report based in part on whistleblower information, much of the budget was executed as administrative costs by multiple organizations; the large-scale aid plan was never fully implemented, and very few homes were built. In 2018, it also came to light that several staff members, including senior officials of the UK NGO Oxfam, who were assisting earthquake victims in Haiti, had sexually exploited local women; despite an internal investigation, the facts were covered up, which was exposed through a whistleblower leak and widely reported.

ICIJ’s website on the Pandora Papers (Photo: Virgil Hawkins)

Leaks and the challenges

Leaks can contribute to building a fairer, more equitable world. However, even when major wrongdoing is exposed through whistleblower information, reporting does not necessarily lead directly to solutions or improvement. As noted earlier, in South Africa, leaks and subsequent reporting are said to have contributed to a change of government, but other factors also played a role. A journalist involved in the investigation later recalled that factional struggles within the ruling party and the timing of the leaks were also crucial factors.

Leaks also raise ethical and legal issues. By disclosing internal information, whistleblowers may violate their employment contracts and, in some cases, the law. However, if those in power are committing illegal or improper acts that implicate human lives, then covering for power for one’s own protection enables wrongdoing. Many whistleblowers are said to take such public-interest considerations into account before leaking.

Even so, even when leaks are highly in the public interest and contribute to society, whistleblowers are often harshly punished for removing information from the government or other entities. When leaks are orchestrated within government, those involved—who would ordinarily be subject to punishment—are rarely held to account.

In deciding whether to publish leaked information, news organizations must make appropriate judgments about the social benefits and harms of disclosure. In democracies with freedom of expression, the media are supposed to play a role in monitoring power and exposing wrongdoing. Even if information was collected through illegal means, as long as journalists themselves did not participate in the illegality, their right to possess and publish it should be protected. Yet in recent years, following disclosures by WikiLeaks and others, state authorities in the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and elsewhere have increasingly threatened such rights of journalists and news organizations. The U.S. government even considered assassinating the founder of WikiLeaks, who had received and published truthful, highly public-interest information.

A demonstration in London calling for Assange’s release. “Stop the CIA’s hitmen” “Free Assange, no extradition” (2022) (Photo: Alisdare Hickson / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0] )

Where is the media headed?

Exposing wrongdoing that causes social harm is often likened to “sunlight as disinfectant.” In deciding whether to leak the truth, or to publish a leak that has been received, the balance between various risks posed by leaks and the public interest will likely be at issue. In democratic societies, however, citizens need an environment in which they can access a wide range of information, express and articulate their own will, and participate in free and fair national governance. For democracy to function, whistleblowers who leak information and the news organizations that publish it are indispensable.

Yet those in power try by various means to block leaks. With advances in information and communications technology making it easier to leak large volumes of information, power has intensified its persecution of both those who leak and those who publish leaked information. This carries the danger of a chilling effect on leaks and on the media.

A study conducted in Spain found that leaks intentionally released from within government were covered more prominently than leaks by whistleblowers, pointing to a tendency for the media to be subordinate to government. In Japan as well, if an issue has low elite interest, it may fail to attract the attention of news organizations; thus, even leaks of high public interest may be neglected.

What lies behind this tendency in the media? It goes beyond a simple value judgment about the benefits of pleasing the government versus the risks of displeasing it. For example, even when a news organization receives a leak, it must verify that the information is not false. Investigating and reporting the information, and weighing the social benefits and risks of publication, can require enormous work. Yet in a financially strained news industry, infotainment has grown and international reporting has declined. Under such circumstances, even if outlets wish to pursue investigative reporting on leaks, how many can accept the risks that leak reporting entails?

Leaks present various constraints and challenges for whistleblowers and for the journalism that seeks to report them. One can only hope the courage of those who leak the truth—and the journalistic spirit to bring that information to the world—will not be lost.

[At GNV, as part of our effort to highlight issues that the world—and Japan—continue to ignore, and to speak for the vulnerable who face them, we welcome information from readers. For information-sharing with GNV, please see here.]

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

0 Comments