HIV/AIDS (*1) is one of the serious illnesses people have long been fighting against. It was once regarded as a certain death sentence, with more than 3 million people infected each year from 1996 to 2001. However, thanks to a range of HIV countermeasures, new infections continued to decline after 2001, and in 2019 fell below 2 million, making it appear the situation was improving. Unfortunately, in the past few years the threat of HIV/AIDS has grown once again. In Africa, where many people are infected, measures that were once highly effective are no longer showing the same impact. What, exactly, is happening in Africa—and around the world?

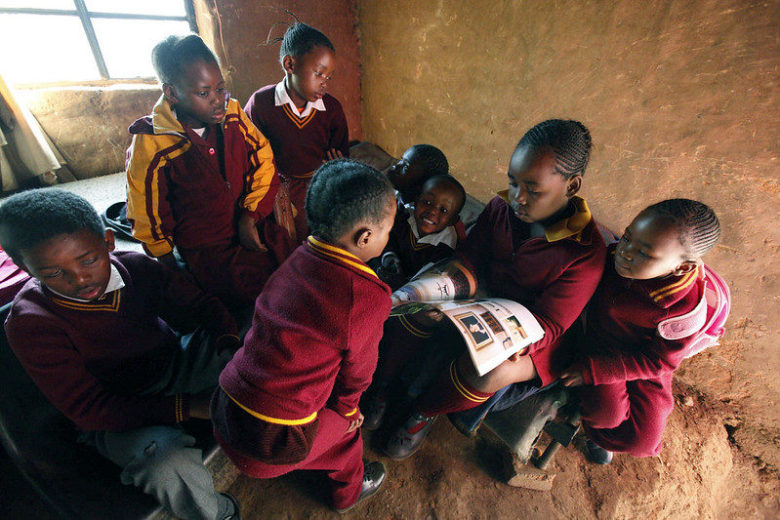

Children looking at an HIV/AIDS awareness poster (Photo: Jeff James / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

目次

What is HIV/AIDS?

What kind of disease is HIV/AIDS in the first place? To begin with, there is a virus called HIV (human immunodeficiency virus). The disease that results when this virus infects a person is AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome). This virus has the property of causing acquired damage to the human immune system. Because the immune system defends the body against diseases and pathogens, when it is damaged, people can become ill with infections they would not normally contract. The routes of HIV transmission are threefold: sexual contact in which an infected person’s bodily fluids enter the body through mucous membranes; blood transmission in which infected blood enters the body through wounds or mucous membranes; and mother-to-child transmission (*2), in which if the mother is infected, the virus can be passed to the child during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding. However, even after infection with HIV, there is a period in which the immune system and HIV itself are in balance, and it takes about 1 to 10 years before the onset of AIDS. During this period, HIV/AIDS can spread without people realizing it.

Human infection with HIV is thought to have come from chimpanzees in Central Africa, with the transmission beginning when hunters killed and ate chimpanzees. Research suggests that infection in humans may have been present as early as the late 1800s. HIV spread across Africa over several decades, and then to other parts of the world. In 1981, the disease was first officially recognized in the United States, and a year later it was named AIDS.

The global spread of HIV/AIDS

So how did HIV/AIDS spread from its origin in Africa to the rest of the world? In Africa, the period during which HIV spread widely is thought to be around the turn of the 20th century. As people gathered and urbanization progressed in colonial-era Africa, HIV transmission also increased. By 2020, the number of people living with HIV worldwide reached about 37.7 million, and the death toll was about 680,000.

Among all regions, Africa still has by far the most infections, and in sub-Saharan Africa, where the damage is severe, there were about 25.6 million people living with HIV in 2021. Countries with particularly large numbers include South Africa with 7.2 million, Nigeria with 3.2 million, and Kenya with 1.6 million—ranked among the world’s top 3 countries by number of people living with HIV.

Why are there so many infections in Africa?

Why, then, is HIV transmission so prevalent in African countries? Several main factors are often cited. First, Africa is the place of origin of the infection. As noted above, there was a long period during which the virus spread within the continent. However, we also need to consider other reasons to explain the spread after the 1980s.

One explanation that has drawn attention in solving this puzzle is the widespread extreme poverty in Africa compared to other regions. Infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS, tend to spread more readily among people with weaker immunity tendencies, and it is well established that malnutrition weakens immunity. There are even studies suggesting that poverty-driven malnutrition, which increases susceptibility to HIV, contributed to the spread of HIV in Africa.

Poverty has also contributed to HIV transmission in another way: disparities in access to treatment. Early access to treatment not only reduces the fatality rate of HIV/AIDS but also lowers infectiousness among people living with HIV. Although treatments were developed during the 1990s—the decade in which HIV infections surged (see below)—the pharmaceutical companies that developed them set extremely high prices and refused to share patents to allow others to produce generics. While the average per capita income in many African countries was below US$800 per year, treatment could cost about US$36,000 per year at one point. As a result, while treatment became available in high-income countries, access in low-income countries such as those in Africa was minimal. After sustained pressure from low-income nations, it was only in the 2000s that treatment finally began to spread in Africa.

Although it is difficult to generalize about a continent with such diverse social structures and cultures by simply calling it “Africa,” sociocultural factors are also cited. Since sexual activity is a primary route of HIV transmission, having an environment in which people can talk openly about sex is important for prevention. This is by no means unique to Africa, and it has been changing in recent years, but traditionally many African communities have viewed discussions about sex as shameful, and conditions for open discussion have been lacking. This problem also breeds stigma (prejudice) against HIV/AIDS. Out of fear of discrimination, many people who suspect they may have been exposed do not get tested for HIV, and even those who know they are infected may be reluctant to acknowledge their status or seek treatment for themselves or their families—an issue reported among many people, especially in the early days of the epidemic.

Differences by region in sexual behavior patterns have also been studied. However, much of the purported evidence carries biases and stereotypes, and it is hard to say that decisive differences with other regions have been confirmed.

Children left behind by HIV/AIDS (Photo: Steve Evans / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Problems caused by HIV/AIDS

There are various problems arising from the spread of HIV/AIDS. The greatest, of course, is the loss of many lives. Many others will live with the disease as a chronic condition. Moreover, the fact that younger generations in particular die from this disease leads to multiple social problems.

One such issue is the problem of orphans due to HIV/AIDS. The number of HIV/AIDS orphans left behind by the deaths of parents living with HIV reached 12.2 million in 2018. This is especially pronounced in Africa. Although it is common for relatives to care for orphans in Africa, stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS leads some to fear the disease and refuse to take in children. In addition, because many adults die from HIV/AIDS, there are fewer relatives available to care for children. Furthermore, many families in Africa are poor, and taking in children can cause further financial hardship. There are also impacts on the education sector. Many children drop out of school to care for relatives living with HIV or to work.

In this way, the adverse effects of HIV/AIDS on younger generations can also slow economic growth. As the workforce shrinks, national industries and labor markets are affected. For example, one study estimated that South Africa would lose 10.8% of its labor force by 2005 and 24.9% by 2020. Across Africa, where the damage is great, HIV/AIDS is a major factor reducing national economic growth by 2–4% per year, with ripple effects on labor supply, productivity, and dependence on imports.

Global responses to HIV/AIDS

As noted above, the number of people living with HIV/AIDS increased, but many efforts have been sustained over many years. First among them is the development of treatments. The first treatment, released in 1987, was a groundbreaking drug called zidovudine (AZT). It inhibits the replication of HIV. However, the effect was limited and it had serious side effects. In addition, the development of resistance over time was a major problem. The next major breakthroughs were saquinavir and nevirapine. These inhibit HIV replication through mechanisms different from AZT and made it possible to combine multiple drugs (ART: antiretroviral therapy), suppressing HIV replication from multiple angles and greatly extending life expectancy. However, these regimens had the drawback of requiring many pills. Through this history, there are now around 30 anti-HIV/AIDS drugs on the market, and with medication, people living with HIV can live similarly to those without it.

Beyond treatment development, a notable effort is the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), established in 1996. Working with 11 other UN agencies, it pools resources and efforts to confront HIV/AIDS. It convenes international meetings on HIV/AIDS, supports national financing for HIV/AIDS, and carries out prevention and treatment. It also collects international data on HIV/AIDS and provides country strategies to curb HIV/AIDS. For example, UNAIDS provides technical assistance to countries to develop strategies to end the HIV epidemic, support policy, and build capacity.

In addition, UNAIDS collaborates with UN member states and NGOs on initiatives to eliminate stigma against people living with HIV through treatment, prevention, and care services.

Another highlight of UNAIDS activities is its goal—in cooperation with UN member states and other UN agencies—to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030. By 2030, it aims to prevent nearly 28 million new HIV infections and 21 million AIDS-related deaths.

A scene from an international conference on HIV/AIDS (Photo: World Bank Photo Collection / Flickr[CC BY 2.0]

Responses to HIV in Africa

In African countries, where people have been living with HIV/AIDS since the early stages of the epidemic, national measures were implemented early. For example, in Burkina Faso, comprehensive HIV measures began as early as 1987. These included heavy investment in HIV treatments, the establishment of support funds for patients and orphans, large-scale training of healthcare workers, and the distribution of condoms. In 2000, the HIV prevalence rate there was 6%, making it one of the lowest in the region.

In Uganda, HIV infection rates dropped significantly after 1993. As early as 1986, the Ministry of Health had been calling on people to prevent HIV/AIDS infection. The message was “abstain from alcohol and live modestly, be faithful to your spouse, and use condoms.” Despite the sensitivity of HIV/AIDS as a sexual health issue, Uganda turned these messages into a national slogan. As a result, the share of the population living with HIV fell from about 18% in 1990 to 5% in 2000.

Kenya made HIV education mandatory. Since 2003, this has been required in school curricula and has attracted many donations. In addition, the supply of HIV treatments led to a sharp decline in new infections. From 2008 to 2010, Kenya doubled its HIV funding to step up efforts to eliminate the virus.

In Ethiopia, with support from the United States, free distribution of HIV treatments was introduced and has continued since 2005. Services for patients were expanded, medical staff were deployed to remote villages, infrastructure was improved, and healthcare facilities were built. In addition, about 2,500 clinics provided antenatal care to prevent mother-to-child transmission, and between 2013 and 2014 about 9.6 million people (1 in 10 Ethiopians) were tested for HIV/AIDS. Ethiopia’s HIV/AIDS measures are considered a model, and in 2020 the prevalence among those aged 15 to 49 was 0.9%.

The slowdown in HIV/AIDS responses and hopes going forward

Although HIV/AIDS responses seemed to be progressing smoothly, their effectiveness has diminished in recent years. According to data released in 2022 by the United Nations, the decline in new HIV infections is stalling. Globally, new infections decreased by only 3.6% from 2020 to 2021, which UNAIDS says is the lowest reduction since 2016.

A similar slowdown is occurring in HIV/AIDS efforts in Africa. A major reason is the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Many countries prioritized COVID-19 measures over HIV/AIDS responses. Restricted access to medical facilities due to COVID-19 and the suspension of treatment transport due to the shutdown of air infrastructure also had a significant impact on HIV/AIDS responses. Moreover, this slowdown has made achieving UNAIDS’ goal of eradicating HIV/AIDS by 2030, mentioned above, extremely difficult.

Even though HIV/AIDS responses are currently slowing worldwide, new hopes are emerging for eradicating HIV. One such hope is a further breakthrough in HIV treatment. In 2021, a “long-acting antiretroviral (ARV) injectable” was approved for use in some countries. This is administered by injection once every 1–2 months, and because the drug stays in the body longer, it can provide sustained effects without taking multiple pills every day. It has been approved, or is slated for approval, in the European Union, the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom; in Africa, a trial involving about 500 participants began in Uganda in October 2021.

Research is also progressing on a new kind of HIV treatment that could have lasting effects unlike before. This approach uses B cells, which produce antibodies against pathogens such as viruses and bacteria, to induce the release of neutralizing antibodies against the disease-causing HIV virus. If realized, it could make it possible to treat HIV/AIDS with a single injection and could even serve as a vaccine.

Beyond treatments, new initiatives are also under way in education. Five UN agencies have launched a new plan, “Education Plus,” to ensure that all girls and boys in sub-Saharan Africa have equal access to free secondary education by 2025, contributing to the prevention of HIV. Teenage girls face a very high risk of HIV infection, and schooling has been shown to significantly reduce this risk. Before COVID-19, about 34 million girls of secondary-school age in sub-Saharan Africa lacked sufficient access to education, and an estimated 24% of young women aged 15–24 were not in education, training, or employment. This plan aims to help them, and five countries—Benin, Cameroon, Gabon, Lesotho, and Sierra Leone—have already signed on.

Conclusion

As described above, the fight between people and HIV/AIDS has been waged around the world—especially in Africa—for many years. Measures advanced markedly from the 2000s onward, but COVID-19 has significantly hindered progress. In the face of these challenges, countries will need to work closely together and respond across sectors beyond healthcare alone. To eliminate suffering from HIV/AIDS by 2030, it is urgent that people change mindsets and put these approaches into practice.

*1 HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system. As the disease progresses, the immune system ceases to function due to the attack, leading to infections by pathogens that would not normally cause illness. AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) is the most severe stage of HIV infection. Viral load is high and the immune system is severely damaged.

*2 Mother-to-child transmission of HIV/AIDS can be prevented through antiretroviral treatment during pregnancy and by avoiding breastfeeding.

Writer: Hikaru Kato

Graphics: Koki Morita

0 Comments