In April 2019, Julian Assange, founder of the whistleblowing site “WikiLeaks (WikiLeaks),” was arrested by British police at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. Fearing extradition to the United States on espionage charges, he applied for asylum to Ecuador seven years earlier and had been protected in the embassy ever since.

The charges against Assange are complex, and some aspects remain unclear, but his arrest has drawn mixed reactions. WikiLeaks is credited with exposing numerous truths that the powerful had hidden from the public, and many warn that his arrest poses a threat to freedom of expression and of the press, sounding the alarm. At the same time, others argue that the actions of Assange and WikiLeaks broke the law and that he should be arrested.

While the details of the arrest, Assange’s personal conduct, and his fate have drawn great attention, less notice has been paid to the significance of the social phenomenon that WikiLeaks set in motion. This article explores the nature of information by examining WikiLeaks and journalism.

Julian Assange delivering a speech (2009) (Photo: Ars Electronica/Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Is WikiLeaks a news organization?

WikiLeaks is a nongovernmental organization that exposes secrets of governments and corporations. Founded in 2006, it advocates ultimate information freedom and operates based on the principle that transparency in governments and corporations prevents abuses of power. It primarily receives, via the internet, unpublished materials such as official documents, emails, and videos from whistleblowers, and has published them in cooperation with other news organizations or directly through its own website. A distinctive feature is its development and use of advanced encryption systems to ensure that whistleblowers can submit information safely; measures are taken to enhance anonymity, such that even WikiLeaks, as the recipient, cannot identify the source of a leak.

Although the details of the organization are unclear, it is thought that in its early years it operated as a relatively loose network of a few full-time staff and numerous volunteers around the world. Many members, including Assange, have hacking experience and expertise in cryptography. In March 2018, Assange’s internet access at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London was cut off; about six months later, replacing him, Kristinn Hrafnsson, a journalist and WikiLeaks spokesperson, became editor-in-chief. Operations rely on donations.

Its social positioning has also been a subject of debate. According to the website (updated through November 2015), WikiLeaks is “a multi-national media organization and associated library” that “specialises in the analysis and publication of large datasets of censored or otherwise restricted official materials involving war, spying and corruption.” However, opinions differ on whether to treat WikiLeaks as a “news organization” and Assange as a “journalist.”

The WikiLeaks website

Indeed, like traditional news organizations, WikiLeaks gathers information from sources and publishes it. Even if information was obtained by illegal means, in countries with established press freedom it is generally considered that when leaked material is of high public interest, the organization that received it from the source has the right to publish it. In such activity, ensuring the authenticity of information and protecting the anonymity of the leaker are regarded as basic responsibilities of journalism. WikiLeaks can be said to have rigorously ensured the reliability of the information it has released, has implemented systems to guarantee source anonymity, and has a track record of protecting it. From this perspective, it shares common ground with journalism.

On the other hand, unlike traditional journalism, much of what WikiLeaks publishes consists of raw documents without context, analysis, or interpretation. Moreover, some of those materials include unredacted names of individuals, which can in some cases damage reputations or even expose people to danger. For this reason, there are many claims that it is not a news organization. Initially, by collaborating with traditional outlets such as the UK’s Guardian, the New York Times in the United States, and Germany’s Der Spiegel, it overcame such hurdles; but when WikiLeaks later began publishing documents directly, it cut ties with those partner media. Some now call it not a media partner but a “publisher” or a “complex source.”

Major disclosures

The scale of the data received by WikiLeaks is enormous. In the decade since its founding, it has enabled the leakage of 10 million documents, and they continue to be published in a searchable form in the site’s library.

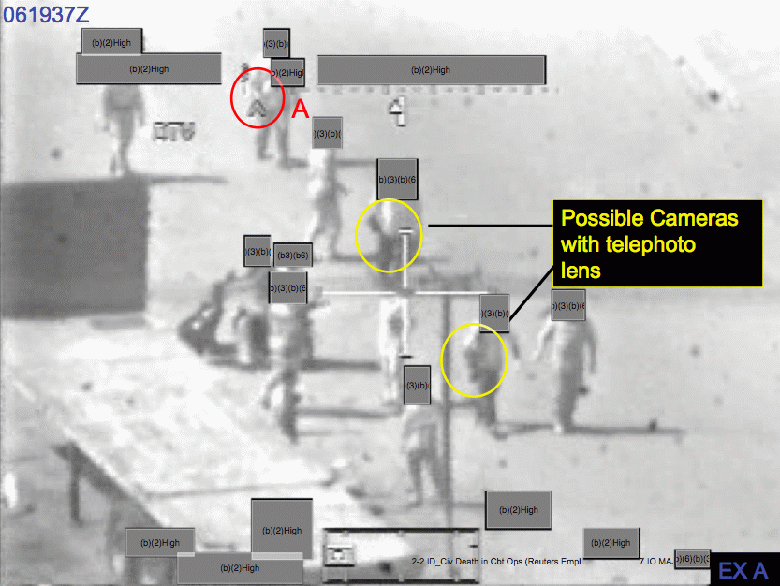

Although it had been active since 2006, it became known worldwide when, in 2010, it released a video of a U.S. military helicopter in Iraq firing on civilians. In the 2007 incident, at least 12 people, including two journalists, were killed, and it became clear that the U.S. military had previously issued false statements about the event. Also in 2010, it separately published U.S. military classified materials on the Afghan War (75,000 documents) and the Iraq War (400,000 documents). Numerous incidents of civilian deaths caused by U.S. forces, as well as torture and other human rights violations by allied governments on the ground, were brought to light. Regarding the Iraq War, the deaths of some 15,000 civilians not previously disclosed by the U.S. government were confirmed.

Image recorded by a U.S. military helicopter in Iraq (2007). Journalists and other civilians were shot dead by the helicopter (Photo: Department of the Army, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division/Wikimedia)

Another catalyst for attention was the U.S. diplomatic cables released that same year. Some 250,000 documents exchanged between the U.S. State Department and embassies and consulates between 1966 and 2010 were published. They included, among other things, indications that then–Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had instructed U.S. diplomats to spy on foreign diplomats and UN officials, and that two years before the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, Japan had been warned by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) of serious safety problems. Information about corruption within the Tunisian government was also included, and the release is said to have been one of the triggers for the protests there that later became known as the Arab Spring.

In U.S. politics, however, what drew the most attention was the release, during the 2016 presidential campaign, of about 20,000 emails from Democratic National Committee (DNC) officials. Containing material unfavorable to Hillary Clinton’s campaign, they became a major issue.

However, the materials published by WikiLeaks did not come only from the U.S. government. There is virtually no country not mentioned in the documents it released. For example, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), negotiated in secret by 12 countries, saw parts of its draft agreement obtained and published by WikiLeaks, revealing that corporate interests were being prioritized over those of citizens in participating countries. Other disclosures included corruption in Kenya and Peru, and corruption in Australia and Southeast Asian countries. Documents and emails exposing the internal affairs of governments and political parties in the United Kingdom, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia were also released.

Beyond governments, numerous disclosures were made through whistleblowers in corporations, banks, think tanks, and religious organizations. For example, the illegal dumping of toxic waste by the Swiss company Trafigura that caused many casualties in Côte d’Ivoire, and a corruption case involving French and German arms manufacturers and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), drew attention. In banking, misconduct at Kaupthing, Iceland’s largest bank that ultimately collapsed, and tax avoidance by the UK’s Barclays were exposed.

Barclays Bank, whose tax avoidance was exposed by WikiLeaks (Photo: Håkan Dahlström/Flickr[CC BY 2.0])

From Stratfor, a major U.S. think tank conducting international risk analysis (sometimes referred to as a “shadow CIA”), some 5 million emails were published. They revealed, among other things, that in India, in connection with the 1984 Bhopal disaster, Stratfor had been hired by Dow Chemical and had spied on victims and bereaved families engaged in protests. Another notable case was the publication of internal documents leaked from Scientology, a religion followed by Hollywood stars and others that has repeatedly drawn criticism.

Impact on journalism

Strictly speaking, WikiLeaks may not be a “news organization.” However, it is clear that it has had a major impact on journalism. In mature democracies, one of journalism’s important roles is to monitor power—that is, to act as a “watchdog” that exposes and deters abuses of power, corruption, violence and wrongdoing, and conduct that harms people, society, and the environment at home and abroad. From this standpoint, the presence of WikiLeaks has been highly significant.

By partnering with WikiLeaks, traditional outlets were able to obtain large volumes of confidential documents and materials that they otherwise would not have had, and several traditional media organizations published exposés together with WikiLeaks. Some outlets and journalists now criticize WikiLeaks, but its activities formed the basis for numerous scoops and articles.

There are also cases in which WikiLeaks’ activities helped strengthen the role of the press in democracy. In Iceland, for example, after banking scandals were exposed, the prime minister was forced to resign, and the new government established IMMI, a body to advise the legislature on enacting laws to protect freedom of information, speech, and expression.

Its influence is seen on the technological front as well. Spurred by WikiLeaks’ anonymous submission system, development advanced on technologies that allow sources to safely leak to news organizations online, and many traditional outlets now routinely use open-source systems such as SecureDrop.

SecureDrop, a tool for whistleblowers to anonymously leak to news organizations

Beyond WikiLeaks

As noted above, while WikiLeaks has greatly influenced journalism, it has also prompted reconsideration of what journalism should be. The path has been arduous. It has at times been called a “terrorist” or a “hostile intelligence service” by the U.S. government, among others, and has come under heavy pressure. For example, that pressure lay behind the removal of its website from Amazon’s servers and the blocking of donations to WikiLeaks via Visa, MasterCard, and PayPal. It has also suffered powerful hacking attacks aimed at stopping the website. It has been bashed by traditional outlets as well. And after seven years of “asylum,” its founder was finally arrested. Despite numerous obstacles, WikiLeaks continues to operate.

However, WikiLeaks also has many problems. Even while championing “transparency” as a principle, it has been far from transparent about itself. Operations grew unstable under Assange’s leadership, and the loss of talented personnel seems to have contributed to a loss of focus. In the end, it has not shaken off the image of being a one-man organization.

There is no need for “WikiLeaks” alone to continue playing the role it has played. What WikiLeaks created could be expanded and refined, established as a new form of “para-journalism,” and by increasing the number of players, both quality assurance and public interest could be enhanced.

We have entered an era of big data, artificial intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT), and advances in such information and communication technologies can be said to be encouraging the concentration and abuse of power and wealth in many countries. Some governments unlawfully collect vast amounts of personal information without our knowledge; companies accumulate and trade personal data, creating a vast underground market. There are also governments that try to legislate to hide information inconvenient to them from their citizens. Precisely because such circumstances exist, the role of the press as a “watchdog” that monitors and checks power is extremely important. Yet given the mass media’s longstanding tendency to accommodate power and wealth, and the worsening financial situation in the news industry, it is hard to say that traditional outlets are fully playing this role.

It does not have to be WikiLeaks, but organizations capable of fulfilling the role WikiLeaks has played could greatly contribute to the promotion of peace, the rule of law, justice, and democracy around the world. Such an entity is needed in today’s world.

GCHQ, the UK’s intelligence agency (Defence Images/Flickr[CC BY-SA 2.0])

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

We’re also on social media!

Follow us here:

「番犬」としての報道の役割や報道の自由は、やはり重要であると思う。

権力者が不都合な情報を自由に統制できてしまえば、権力の濫用は必ず起こる。

運営には様々な障壁があるが、ウィキリークスのような「準ジャーナリズム」の役割の重要性をもっと社会が認識していく必要があると思った。

最後のセクションにおける考察に感銘を受けました。権力の濫用を監視する機能は、もはや政府の(建前の)良心にも憲法にも期待できない。したがって、ウィキリークスのような政府と関わりを持たない第三者の機関を、法によって保護しつつ権力濫用の番犬として公式に役立てるべきだと思います。本来のジャーナリズムのあるべき姿、ジャーナリズムの哲学を今一度見直す必要があると感じました。

確かに秘密文書を持ち出すのは違法かもしれませんが、やっぱり内部告発も、ウィキリークスも、必要だと思います。

本来のジャーナリズムとは何かということを考えさせられました。

昨今はマスメディアがマスゴミと呼ばれるようになり、国家システムの傀儡・ポチに成り下がっている。

国家システムが歴史上、常に悪なので、「全ての国家が悪」になってしまうのは致し方無い。

(例) 課税は常に悪/軍は常に悪/スパイは常に悪

中でもファイブアイズは「米国侵略全史」という本が出る位に、悪なのである。

しかしその反面、世界を進歩させてきたと言えるし、

その恩恵に西側諸国が浸かっているのである。欧州、インドを始め、日韓台湾すらもだ。

インドなどは、自国の言語体系が多岐に渡り複雑なので、

共通語として英語が便利というくらいで、外国語が公用語なのだから、

日韓台湾からすれば呆れかえる側面すらある。

また、情報技術=スパイ技術=諜報技術だが、裏を返せば、

世界中の悪事が伝わってくるし、きゃつら「全ての国家」はその「悪事」を隠そうともしない。

つまり国家というのはそもそもが「テロ国家しか存在しない!」とすら言える。

東西諸国とは、つまり「テロ政党」が「テロ組織」を集合させ「テロ国家」を作り上げているだけのことである。

同じ「ギャング国家」「ならずもの国家」の集散であれば「利権」「うまみ」で判断する、

というのが「国民の道理」であろう。

それが上手なのが、ファイブアイズだったとも言える。

だから英連邦というゆるーい経済圏に60カ国ほどが加盟している。

それらの「国家を形成する大企業が悪」であるのは当たり前である。