In late June 2025, a series of reports released by UN bodies and other organizations laid bare the grave state of development and international cooperation. The UN-affiliated Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) published a report on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), warning that progress is “seriously off track.” It stated that, at the current pace, none of the 17 SDGs is expected to be achieved by 2030.

In the same month, a UN expert group compiled a report on the rapid surge of debt burdens in low-income countries. Today, around 3.4 billion people live in countries that spend more of their national budgets on interest payments than on essential social services such as health and education. Meanwhile, according to a report by the international NGO Oxfam, roughly half of the world’s population lives in poverty, while the richest 1% have amassed at least US$33.9 trillion in wealth since 2015.

The timing of these reports was coordinated to coincide with the UN’s 4th International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4), held in Seville, Spain, from June 30 to July 3, 2025. Since the process was instituted in 2002, the conference has been held only four times; the last one was in 2015. This gathering of heads of state was positioned as a rare opportunity to address global development challenges. In his opening remarks, UN Secretary-General António Guterres highlighted the US$4 trillion gap between development needs and available financing, underscoring its gravity. At the same time, the UN itself is facing an existential crisis. It is severely underfunded, to the point of being unable to maintain even basic staffing levels.

Despite this dire situation, Japanese media, while publicly emphasizing interest in the SDGs, paid little attention to the bleak outlook that the goals will not be met, to the aforementioned reports, or even to the UN’s funding crisis. The Financing for Development conference itself received almost no coverage. This article examines how the media reported—or failed to report—these developments and issues, focusing on three newspapers: the Asahi Shimbun, the Mainichi Shimbun, and the Yomiuri Shimbun.

Group photo of the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development (Spain) (Photo: La Moncloa / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0])

目次

The SDG crisis

The SDGs, adopted at the UN in 2015, comprise 17 goals covering the major development challenges confronting the world. They span a wide range of issues, including ending extreme poverty and hunger, ensuring health and education for all, achieving gender equality, reducing economic inequality, protecting the environment, and strengthening peace. Each goal contains multiple specific targets—169 in total.

The SDGs were formulated under the slogan “leave no one behind.” Central to this is ensuring that the basic needs of the people and communities in the most disadvantaged positions are met. Achieving this, however, requires the engagement and responsibility of the wealthiest countries, because many of the development challenges facing low-income countries are deeply tied to the historical responsibility and current actions of high-income countries. According to the UN, “leaving no one behind” is not simply about “reaching the poorest of the poor. It means combating discrimination and rising inequalities within and across countries—and their root causes.”

The SDGs were set on a 15-year timeline, and only five years remain. As noted above, according to the SDSN report as of June 2025, none of the 17 goals is on track to be achieved. Looking at the individual targets within each goal, only 17% are projected to be met; the remaining 83% are stagnating or even reversing. The report also provides country-by-country SDG scores, with the five lowest-ranked countries being South Sudan, the Central African Republic, Chad, Somalia, and Yemen.

Refugee camp in Bangladesh home to Rohingya people (Photo: UN Women / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Coverage of the SDG crisis

So how did Japanese media report this sobering reality around the SDGs? In short, they scarcely did. The Asahi Shimbun did mention the SDSN report itself, but its focus was on Japan’s ranking in the SDG index. While it highlighted Finland as the top-scoring country, it did not touch on the countries where the largest numbers of people are being “left behind.” Most critically, the paper did not mention at all in its print edition the core fact that, on the current trajectory, the world as a whole will fail to meet all 17 goals. A brief note appears only at the end of an article on Japan’s ranking posted on “SDGs ACTION,” Asahi’s dedicated SDG web page. However, this was not in the print edition, and thus was accessible primarily to readers already following SDG issues (Note 1).

The Mainichi Shimbun and the Yomiuri Shimbun did not mention the SDSN report or its findings at all. In June 2015, the Mainichi covered a government report on Japan’s performance on gender-related SDGs, but this was confined to a domestic issue. In March 2025, it also ran an article on the Trump administration’s negative stance toward the SDGs, but did not address global SDG progress. The Yomiuri Shimbun ran four articles in June 2025 with “SDGs” in the headline, all on domestic topics, and did not touch on the SDSN report.

In recent years, Japanese media have shown strong interest in the concept of SDGs itself. That is precisely why it is astonishing that they have virtually ignored the major fact that the world is not on track to achieve any of the goals. What emerges from recent coverage across the papers is a fundamental misunderstanding of the intent and design of the SDGs. First, the focus on country “rankings” overlooks the core SDG principle of “leaving no one behind.” In other words, it fails to reflect the idea that those in the most vulnerable positions worldwide should be prioritized.

Second, this reporting approach disregards the global interconnectedness of the SDGs and the complexity of the challenges facing the planet. Achieving the SDGs is neither a purely domestic matter nor a competition between countries on a league table. All countries must work together to achieve the goals collectively. For example, Japan’s efforts on climate action are important, but the causes and impacts of climate change cross borders. If the world as a whole fails to meet the targets, global warming will not be stopped.

For an in-depth analysis of SDG coverage, please see this article.

Hiroko Kuniya of the Asahi Shimbun’s SDGs Project speaks at Davos with Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte (Photo: World Economic Forum / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

International Conference on Financing for Development

Let us turn to one of the key international forums for addressing global development issues: the International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD). The first conference was held in Monterrey, Mexico, in 2002 and was attended by leaders from more than 50 countries. Its outcome, the Monterrey Consensus, covered several critical areas, including mobilizing domestic and international resources for development, reducing external debt, and addressing structural issues in the international financial and trading systems.

The second conference (FfD2) took place in Doha, Qatar, in 2008, amid a spreading global financial crisis. Many heads of state attended; notably, however, the leaders of major high-income countries and the heads of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) did not. The meeting adopted the Doha Declaration, which reviewed implementation of the Monterrey Consensus and outlined future directions.

The third conference (FfD3) was held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 2015, and adopted an Action Agenda covering a broad array of development-related issues. Particularly notable was a push by many low-income countries to establish an international institution to address tax matters in response to global tax avoidance and evasion. This came against the backdrop of widespread use of tax havens to facilitate tax avoidance. However, the proposal was blocked by high-income countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan.

The fourth conference (FfD4) was held in Seville, Spain, in 2025 and was attended by about 60 heads of state. The meeting concluded on July 3 with a 38-page outcome document that, as before, covered a wide range of issues to advance development. Another significant development was a joint proposal by Spain and Brazil to strengthen intergovernmental coordination to ensure effective taxation of high-wealth individuals.

Representatives of the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) at the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development (Photo: UN Trade and Development / Flickr [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Coverage of the Financing for Development conference

How did Japanese media report on these four conferences? The first Monterrey conference in 2002 received a certain level of attention. The Yomiuri Shimbun ran 11 articles before, during, and after the meeting; the Asahi Shimbun ran 10; and the Mainichi Shimbun ran 6.

After 2002, coverage of the conference evaporated. For the Doha conference (FfD2) in 2008 and the Addis Ababa conference (FfD3) in 2015, none of the Asahi, Mainichi, or Yomiuri dispatched reporters or even mentioned that the meetings were held. Regarding the 2025 Seville conference (FfD4), the Asahi Shimbun published an op-ed by the UN Secretary-General on development ahead of the meeting, noting it would be held. However, none of the papers reported on the opening, proceedings, or outcomes of the conference.

The UN’s financial crisis

The UN is a central driver of the SDGs, the host of the Financing for Development process, and one of the most important forums for development more broadly. Although 2025 marks the 80th anniversary of the UN’s founding, it is far from a celebratory year. The organization is facing what may be the worst financial crisis in its history. One of the main causes is member states’ failure to pay assessed contributions. The UN’s finances are supported by member states according to a scale of assessments based on factors such as population, gross national income (GNI), and debt burden. However, many countries are failing to meet their obligations, resulting in a funding shortfall of US$2.4 billion as of April 2025—US$1 billion more than the previous year.

Against this severe funding backdrop, calls are growing within the UN for major reforms, with concrete proposals and discussions underway. In March 2025, Secretary-General Guterres launched the “UN80” initiative, beginning reforms aimed at streamlining and simplifying the UN’s work as a whole. Details were further clarified in May, indicating plans for a sweeping overhaul, including a reorganization of the entire system. A leaked internal memo also noted that the UN was considering a major restructuring that could include a 20% reduction in staff. The discussion goes beyond fiscal consolidation, touching on the UN’s raison d’être and structure itself.

UN Headquarters, New York, USA (Photo: John Gillespie / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

The overall cost of the UN’s activities is, in relative terms, not large. Global military spending reached US$2.7 trillion in 2024, while the UN’s regular budget for 2025 is just US$3.7 billion. In addition, UN peacekeeping operations cost a further US$5.6 billion. Beyond this, various UN agencies seek separate funding from countries and other donors for humanitarian operations worldwide, such as providing support to refugees and food assistance to countries facing famine.

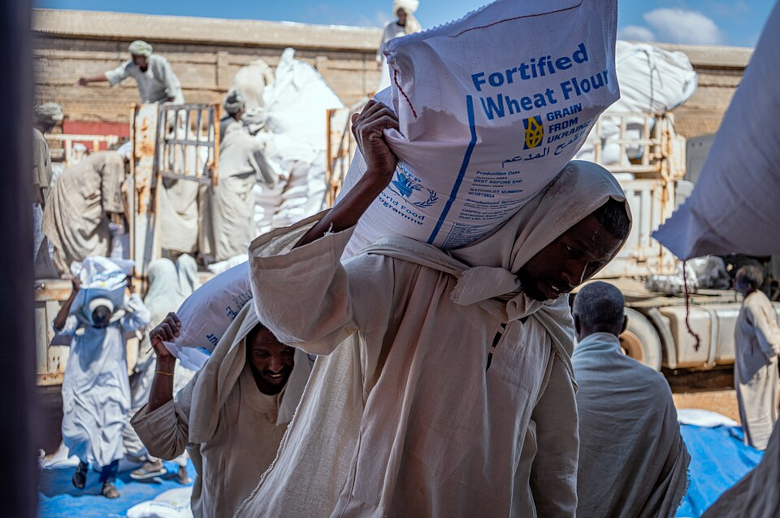

Funding for this humanitarian work is also in deep crisis. In 2025, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) appealed for US$47 billion to reach 180 million people worldwide. By midyear, however, contributions from donor countries and others amounted to only 13% of the requirement. As a result, in June 2025 the UN was forced to issue a significantly scaled-back appeal to prioritize within the limited resources. Consequently, even as the number of people suffering severe hunger is rising globally, the UN World Food Programme (WFP) is being compelled to drastically reduce the number of people it serves. In other words, food assistance to those most in need is not being delivered due to lack of funds.

Coverage of the UN’s financial crisis

As we have seen, this is a crisis of historic proportions for the UN as an organization—and for humanitarianism itself. The lack of sufficient aid is leading to large-scale loss of life in many parts of the world. Yet Japanese media do not appear to fully grasp the seriousness of the situation.

In the first half of 2025, there were only a handful of articles by Japan’s major newspapers on the UN’s funding issues. The Yomiuri Shimbun ran three articles primarily on this topic; the Asahi and Mainichi ran two each. Many of these treated the UN crisis in the context of the impact of US aid cuts, with few delving into the structural funding shortfalls facing the UN system as a whole. Some coverage addressed cuts to individual humanitarian agencies like the WFP, but most focused on reductions to food assistance in specific places such as Gaza. There was little mention of the cuts affecting African countries, where food-related humanitarian crises are most acute. With the exception of a single Yomiuri article on US cuts to the WFP, there were essentially no pieces treating the global funding crisis facing humanitarian agencies as a whole. Moreover, none of the three papers addressed the UN’s financial crisis—or the threat to its overall operations—in editorials.

Comparing the sparse coverage of the UN crisis with other topics makes clearer where Japanese newspapers’ attention lies. For example, in the first half of 2025, coverage of the “crisis” surrounding Harvard University in the US far outstripped reporting on the UN crisis and its associated loss of life. In response to moves such as the Trump administration’s aid cuts and changes to visa policies for international students, the Mainichi ran 33 articles, the Yomiuri 28, and the Asahi 17.

WFP aid supplies being unloaded from a truck, Sudan (Photo: Abubaker Garelnabei (WFP) / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0])

Not merely a matter of “charity”

The world is currently facing a severe shortfall in humanitarian funding. This retrenchment is occurring not only in emergency responses to crises, but across official development assistance (ODA) for long-term cooperation. Western countries, among the largest donors, are sharply cutting ODA. Even before this, most major economies, including Japan, have long provided amounts far below the internationally agreed target (0.7% of GNI) set half a century ago (Note 2). Moreover, many countries make large pledges at international conferences and summits but fail to deliver once media attention fades. This phenomenon is sometimes called “ODA debt.” In fact, there are estimates that, over the past 20 years, undelivered aid promised by the G7 and others to African countries amounts to around US$72 billion.

However, the current stagnation in development and lack of SDG progress cannot be solved merely by increasing the volume of aid. More effective and sustainable solutions lie in rethinking the structures of the various systems that govern the world today. Many of the international frameworks for trade, finance, taxation, and investment work to the advantage of high-income countries and impose unfavorable conditions on low-income countries. These systems and structures are major drivers of the stark global disparities in wealth.

In his opening address at FfD4 in Spain, the UN Secretary-General strongly criticized illicit financial flows, tax avoidance, and the current international debt system as “unsustainable, unjust, and unbearable.” He concluded with these words: “This conference is not about charity. It is about restoring justice and human dignity. This conference is not about money. It is about investing in the future we want to build together.” Ahead of the meeting, the head of Amnesty International also called for structural reforms in development financing, including international taxation and debt reform, redirecting fossil fuel subsidies to clean energy investment, and “reforming international financial institutions and fostering a more inclusive development and financing system.”

Vast amounts of wealth continue to flow from low-income countries to high-income ones—through tax avoidance, unfair trade, and excessive debt service. Furthermore, climate change driven by the industrial activities of high-income countries has inflicted immense damage on the people, environments, and economies of low-income countries. Yet high-income countries continue to resist meaningful reforms to address these problems.

The Spanish Prime Minister and the UN Secretary-General speaking at the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development (Photo: La Moncloa / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0])

Background to the coverage

The lack of interest shown by Japanese media in the issues discussed above is consistent with the findings of many of GNV’s past studies. In terms of volume, international coverage is skewed toward countries where power and wealth are concentrated, while the hardships faced by the vast majority of the world’s people receive little attention. In other words, the poorer a country is, the less likely it is to be covered. It is also important to note that the worldview of Japanese media is strongly influenced by the US perspective.

As a result, Japanese media tend to focus more on the responses of the Japanese government—or the US government—to global development problems than on the problems themselves. Coverage of the UN likewise tends to center on how the US government approaches the organization, rather than on the UN’s own actions. In other words, the reactions of Japan or major powers are often prioritized over the substance of international issues.

The lack of coverage of the Financing for Development conference in Japanese media may have less to do with the content of the meeting than with who attended. Even if about 60 heads of state were present, the absence of the US president, the Japanese prime minister, and other leaders of major high-income countries may have led Japanese media to deem it of “low news value.”

Another factor may be that the fundamental changes sought by the conference—reforms to international systems surrounding debt, taxation, fossil fuel subsidies, and unfair trade—could threaten the economic interests enjoyed by Japanese corporations around the world. This includes many large companies that advertise in or are otherwise connected to the major newspapers. The newspapers themselves are large corporations. The Japanese government, which sees one of its roles as promoting the expansion of major domestic companies’ interests, is also far from enthusiastic about the kinds of global system changes sought at the conference, as seen in its resistance to global tax reforms. These conditions may help explain why Japanese media do not dig deeply into such issues.

A mother and child selling water in a village in Ethiopia (Photo: Rod Waddington / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0])

While Japanese media show a certain level of interest in the SDGs, their coverage diverges significantly from the SDGs’ original purpose and actual progress. It is skewed toward promoting the areas of interest of Japanese companies and publicizing upbeat claims that they are “contributing” to the SDGs, while rarely addressing the environmental destruction and human rights abuses caused by those same companies that impede SDG achievement. Much of the coverage focuses on domestic environmental measures and initiatives, with very little attention paid to core SDG issues such as global poverty and inequality. The fundamental SDG principle of “leaving no one behind” is scarcely visible in Japan’s SDG reporting.

It is hard to avoid calling contradictory the stance of Japanese media that profess interest in achieving the SDGs, yet fail to inform readers that, under current conditions, achievement is highly unlikely. It is equally puzzling that they virtually ignored a major international conference held for the first time in a decade to discuss global development financing.

Extensive information on the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) is available on the official website, including video materials of the discussions. Even if the major Japanese newspapers did not send reporters to the venue, opportunities for reporting remain.

It is not too late. Now is precisely the moment for the media’s posture to be tested.

Note 1: In June, an online article unrelated to the SDSN report also addressed the issue of child labor in relation to achieving the SDGs.

Note 2: In 1970, the UN General Assembly agreed on a target for high-income countries to provide 0.7% of their gross national income (GNI) as aid. Japan’s 2024 ODA was only 0.39% of GNI.

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

記事ありがとうございます。このニュースは中で分析されている通り、日本のメディア(大手だけでなく独立系も含めて)ほぼまったく報じられていないかと思います。SDGsについても以前よりかなり言及は減りました。特に大手メディアはかなり近視眼的になっており、まさに「日本のメディアは、世界の開発問題そのものよりも、そうした問題に対する日本政府の対応、あるいはアメリカ政府の対応に関心を向けがち」だという意見には全く賛成いたします。もう少し、世界の一員である、自分たちの行動が世界、特に貧困国に影響を及ぼしているという自覚をメディアが持ってほしいと考えます。

SDGsバッジをつけている人はどれくらいこういう問題を知っているのだろうと思った。SDGsはもちろん、国連のこうした危機についてもっと多くの人が関心を持つべき。