In January 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump ordered an almost across-the-board 90-day freeze on foreign aid. The administration accused the independent government agency responsible for aid, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), of widespread waste and of undertaking many activities that do not align with U.S. national interests. Though challenged in court, six weeks after the freeze order, the Secretary of State announced an 83% cut to USAID programs.

The freeze drew widespread concern and criticism for its immediately life-threatening impact on aid programs worldwide, including emergency health and food assistance. However, some agree that USAID’s activities warrant review. They point to long-term problems at USAID. For example, opinion pieces in the U.S. media have included claims that USAID has “functioned as an instrument of regime change operations, election interference, and the destabilization of countries around the world.”

The implications for the news industry also became part of the debate. In February 2025, Trump suggested that USAID had been funding U.S. news outlets. Many outlets rejected the claim as false, but USAID has indeed provided substantial assistance to media organizations around the world. However, USAID is not the only U.S. government body that funds foreign media; other agencies also actively engage with the global media environment.

This article briefly reviews Japanese media coverage of the 2025 developments surrounding USAID and examines how the U.S. government has funded media organizations worldwide and what effects that funding has had.

USAID relief supplies (Photo: US Department of Agriculture / Flickr[CC BY 2.0])

目次

Japanese coverage of the USAID funding freeze

Japanese media showed a certain degree of interest in the Trump administration’s actions regarding USAID, and major newspapers ran several articles on the topic. From the initial announcement of the foreign aid freeze in January 2025 to the decision in March to cut most aid, the Asahi Shimbun published 11 articles on the subject. The Yomiuri Shimbun and the Mainichi Shimbun each ran eight.

Beyond reporting on the administration’s decisions and the responses to them, articles focused mainly on the harm to humanitarian projects worldwide. For example, there was an article discussing how the freeze would affect projects such as refugee assistance, demining, and treatment for people with chronic illnesses. The Asahi Shimbun translated and reprinted an emotive New York Times column by Nicholas Kristof that called the dismantling of USAID “a tragedy for humanity.”

This focus is of course important. The decision to freeze aid had grave consequences for humanitarian work, with immediate negative effects. But the broader context—what USAID has aimed to do and how it has operated to date, and the problems associated with such aid—is also important. In articles on the freeze and dismantling of USAID, there was little mention of USAID’s political activities or the darker sides of its history as an instrument for advancing U.S. national interests.

As for reporting on USAID activities beyond humanitarian assistance, we found little more in the major papers than a single line in a Mainichi Shimbun editorial (March 2, 2025) stating that “USAID has also borne a U.S. diplomatic strategy of supporting democratization in developing countries, etc.” Relatively neutral support for democracy is indeed part of what USAID has done, but since its establishment in 1961 its activities have had other darker sides as well. For example, during the Cold War USAID provided various forms of support to authoritarian regimes friendly to the U.S. government. USAID also worked with the CIA to teach police and security forces in U.S.-aligned Latin American regimes torture techniques.

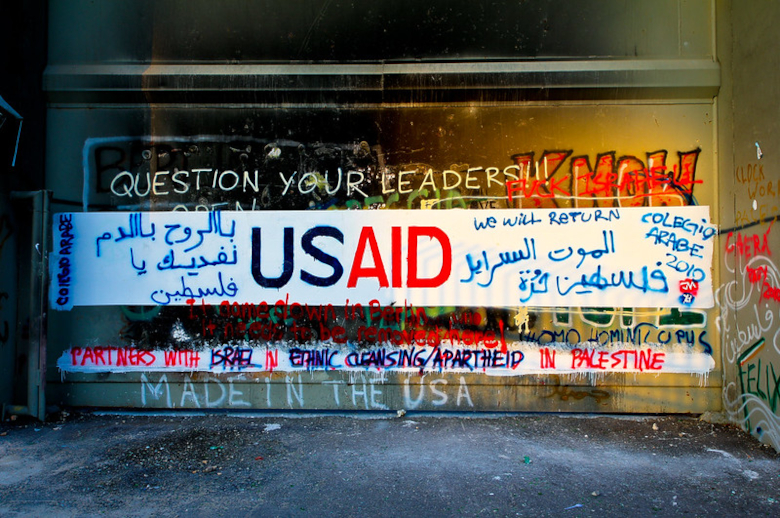

Anti-USAID graffiti on the wall between Israel and Palestine (Photo: Asim Bharwani / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In recent years, the notion of “democracy assistance” has often meant engaging in election interference or contributing to regime-change efforts—toppling leaders deemed unfriendly to the United States. In Serbia’s 2000 elections, for example, USAID provided extensive funding for political consultants and opposition election support, and distributed 5,000 cans of spray paint for anti-government graffiti and 2.5 million stickers bearing anti-government slogans. In Cuba in 2010, USAID covertly sought to introduce a social networking platform with the long-term aim of provoking political demonstrations against the government. By contrast, it is hard to find robust USAID-backed efforts at democracy promotion or regime change in authoritarian countries friendly to the United States.

USAID and the media

One of USAID’s activities is support for foreign media outlets and journalists. Japanese media covered the debate over USAID’s ties to media only in a limited way, and mainly to deny such connections. Officials including Trump claimed that USAID had funded U.S. outlets such as Politico and the New York Times, but major Japanese newspapers that covered the claim ran an article denying that any such facts existed. They also rejected social-media rumors that the BBC in the UK and many Japanese news organizations received such funding, labeling them “baseless claims” and “conspiracy theories.” Japanese newspapers also published articles denying rumors that they themselves had received funding from USAID.

Notably, while Japanese media denied claims that they themselves had received USAID funding, they did not report the fact that USAID has funded many media organizations around the world and played a major role. In one article, the Mainichi Shimbun merely stated that USAID “has also aided independent media in authoritarian countries,” without providing further detail. The Asahi Shimbun and Yomiuri Shimbun did not touch on the existence of USAID’s funding for media outlets around the world.

In fact, a USAID fact sheet cited by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) (now removed from the USAID website) stated: “In 2023, USAID provided training and funding to 6,200 journalists and supported 707 non-state media outlets.” Furthermore, the foreign aid budget appropriated by Congress for 2025 included roughly $270 million to support “independent media and the free flow of information.” In the wake of the U.S. aid freeze, many media outlets around the world that rely on this support have been forced to cut staff and are “desperate to survive,” according to some assessments.

Reporting by journalists supported via Internews with USAID funding, Indonesia (Photo: USAID / Flickr[CC BY-NC 2.0])

Independent media?

Much U.S. assistance to foreign media is distributed through U.S.-based intermediary media organizations. These organizations use funds received from USAID to provide financial support and training to outlets in other countries. For example, Internews is a nonprofit media organization that has supported thousands of outlets and journalists in more than 100 countries. Since its founding in the 1980s, the organization has relied heavily on USAID funding. The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) is another large intermediary media organization supporting journalism worldwide. It too originated with USAID funding and has since grown to operate on an annual budget exceeding $20 million, of which roughly half is provided by USAID and other U.S. government bodies.

Internews and OCCRP, though highly dependent on USAID and other government funds, assert that the projects they implement and the outlets they support retain editorial independence and are not influenced by donors.

However, such assertions do not necessarily mean that USAID lacks influence over the activities of the outlets it supports. For example, under projects funded by USAID, the agency holds the authority to approve senior staffing and annual work plans. Even if USAID does not reject staffing or plans, outlets and intermediary organizations may design them to align with U.S. government interests. A representative of a Bosnian outlet receiving USAID funding via OCCRP said in an interview, “When you receive funding from the U.S. government, there are topics you don’t pursue. The U.S. government has interests that take precedence over anything else.”

The precise extent of USAID’s direct influence is unclear, but if the interests of the U.S. government and those of intermediaries and outlets align, day-to-day influence may matter less. One of Internews’s founders observed early on that the organization was “beginning to structure itself around getting government funding,” creating an “intersection” between U.S. “political interests” and Internews.

Editor-in-chief of the Ukrainian outlet Ukrayinska Pravda, which received USAID support (Photo: Casa de America / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

It is hardly surprising that USAID tends to heavily fund projects in places and through methods that advance U.S. interests. For example, there is very little among OCCRP’s work that exposes scandals involving U.S. companies. Meanwhile, USAID has provided substantial funding to many Ukrainian media outlets. Some of the grant agreements include specific political objectives. For instance, a Ukrainian outlet producing English-language content for Western media received funding from USAID via Internews in 2021; reportedly, the agreement included objectives such as “undermining Russian information operations” and “strengthening international support for solidarity with Ukraine.”

When outlets depend heavily on donors, to what extent can they truly be called “independent media”?

Other influences

A downsizing of USAID does not mean the end of the U.S. government’s ability to disseminate information aligned with its interests worldwide. The U.S. government has multiple instruments for influencing the global media environment. For example, the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM) is an independent government agency that owns its own media outlets. USAGM operates two outlets—the Voice of America (VOA) and the Office of Cuba Broadcasting—and funds four more: Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Radio Free Asia, the Middle East Broadcasting Networks, and the Open Technology Fund. Through these, USAGM provides content in 64 languages to more than 400 million users.

USAGM claims editorial independence, but its editorial policies and statements reflect strong alignment with U.S. foreign policy. On its website, it states that it “ensures that programming decisions reflect the interests of the United States.” In another document, it states that it is committed to “counter malign influence by the People’s Republic of China, Russia, Iran, and other authoritarian regimes and non-state actors.” The Trump administration is reviewing funding for USAGM and may consider cutting support and tightening control over the organization, a possibility.

Voice of America (VOA) headquarters (Photo: Rhododendrites / Wikimedia Commons[CC BY 2.0])

While the U.S. military is not a media organization, attempts by the military to influence foreign audiences through media have a long history. When U.S. forces invaded and occupied Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003, they hired contractors to build media infrastructure, outlets, and newscasts to provide information—primarily aimed at casting the occupying forces in a favorable light—to local populations. Such projects sometimes involved cooperation with USAID. They also paid local outlets to publish pro-U.S. news stories, some of which were presented as written by local civilians but were in fact written by U.S. soldiers. Beyond media, the U.S. military has employed numerous psychological operations to influence foreign populations and leaders.

The CIA also has a record of getting outlets around the world to carry stories containing disinformation and propaganda. In large-scale information operations exposed in the 1970s, the CIA infiltrated news organizations worldwide and paid journalists to channel CIA-originated content into newspaper articles and television reports.

In addition, there are organizations that are not officially government agencies but receive direct U.S. government funding and support the operation of foreign media. For example, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) is a nonprofit but has close ties to the U.S. government. One of NED’s co-founders even stated in 1991, “A lot of what we do today was done covertly 25 years ago by the CIA.” Although its name suggests it works “for democracy,” NED appears to decide how to support countries less on the basis of democratic standards than on whether they are antagonistic to the U.S. government, it would appear. NED has a long history of involvement in election interference abroad, and media support is part of that activity. Like USAGM, NED also faces the prospect of funding cuts under the Trump administration.

Media literacy training by Internews and USAID, Kazakhstan (Photo: USAID Central Asia / Flickr[CC BY-ND 2.0])

Conclusion

The abrupt freezes and cuts targeting USAID and other bodies involved in media support may at first glance look like measures to reduce wasteful spending. However, they can also be seen as part of a reorganization of power and control within the U.S. government. Some observers suggest that the Trump administration is seeking to bring the activities of organizations like USAID—which had a degree of autonomy from the administration of the day—more directly under its control.

From the outset, such foreign aid and support for media around the world have not been undertaken purely as charity or solely to advance global democracy and press freedom. The Trump administration likely recognizes that these programs are designed to promote U.S. national interests and that these organizations can wield significant influence. At this stage, it remains unclear how such aid activities will be reconfigured.

In any case, U.S. influence in shaping the global media environment goes beyond the support programs mentioned above. More generally, because news organizations tend to focus on powerful people and states, U.S. actions and perspectives are heavily reflected in media around the world. A previous GNV article discussed the mechanisms behind this. Moreover, this influence is exercised not only by the U.S. government but also by major U.S. media. For instance, another GNV article has shown that the New York Times’ international reporting influences how Japanese outlets cover international news.

While this piece has focused on news organizations in the series of events around U.S. foreign aid cuts, it also presents an opportunity to reflect on other issues such as international relations and inequality. It is to be hoped that Japanese media will adopt a more critical stance toward such developments and report in ways that raise questions from a broader perspective.

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

「ヤクザの炊き出し」は正義か?

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.