In June 2024, Namibia’s High Court declared the criminalization of same-sex conduct unconstitutional. This means homosexuality has been legalized in Namibia and the rights of LGBTQ (※1) people have improved significantly. In Botswana, LGBTQ supporter Duma Boko assumed office as president in November 2024. He is a human rights lawyer who previously won a case contesting the legal recognition of an LGBTQ rights organization. After his election, he has also stated he will protect the rights of LGBTQ people.

Meanwhile, in December 2024, a new penal code took effect in Mali, making same-sex conduct illegal and criminalized. It also appears that people who express favorable attitudes toward homosexuality may be prosecuted. Thus, while some African countries are moving to strengthen LGBTQ-related rights that were long severely restricted, others are moving in the opposite direction. How, then, have the legal systems and attitudes toward LGBTQ people developed?

A clandestine Pride event held following the passage of an anti-LGBTQ law (Uganda) (Photo: iain statham / Shutterstock.com)

目次

Overview

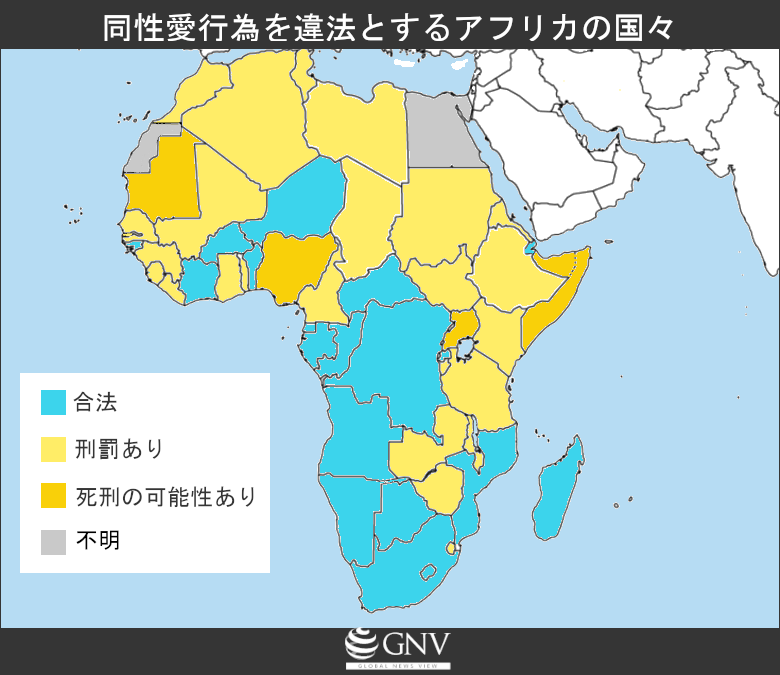

First, a brief explanation of the rights of homosexual people in Africa. In Africa, same-sex conduct is criminalized by law in 29 out of 54 countries (※2). This means more than half of African countries deem same-sex conduct illegal, a share that is higher than in other regions. In 4 countries—Uganda, Somalia, Mauritania (※3), and parts of Nigeria—the death penalty is also possible.

Next, the rights of transgender people. In Africa, 7 countries allow legal gender changes on official identification. However, most other countries have no specific laws. The existence of gender identities other than male and female, such as non-binary (※4), is not legally recognized in any country. Kenya, on the other hand, is the only African country that legally recognizes intersex (※5) people, and “intersex” has been added as a gender option in its census.

The African Union, a regional body, does not explicitly address the rights of LGBTQ people, but its human rights treaty, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, recognizes protection from discrimination based on sex and status and equality for all. However, it has not taken an official stance on whether sexual minorities are protected.

For Egypt and Western Sahara marked as unknown, see below (※6)

Pre-colonial history

As noted, Africa has more countries with anti-LGBTQ policies than other regions. However, this trend did not continue from ancient times. Prior to the 19th century, there are historical cases of acceptance of same-sex relationships and gender identities beyond the male-female binary. In Egypt around 2400 BCE, a tomb was discovered (※7) where two men were buried embracing as lovers. It has also been suggested that a third gender may have been recognized.

Such history existed not only in North Africa but also in sub-Saharan Africa. In the 16th century, in what is now Angola, there are records of men dressing as women having husbands, and the existence of transgender people. At the same time, although not heavily suppressed, there is evidence that negative perceptions of LGBTQ people existed. It remains unclear how exceptional the cases recognizing LGBTQ people were.

Thus, before the 19th century there are confirmed examples of LGBTQ people being accepted by society. Later, from the 19th to the 20th century, Christianity was missionized and European colonization progressed in sub-Saharan Africa. Influenced by Christianity and colonial-era laws, anti-LGBTQ sentiment and heteronormative thinking grew stronger, exerting a major influence on subsequent culture and law.

A similar trajectory occurred in regions where Islam is practiced, such as North and West Africa. For example, in the Ottoman Empire, which ruled North Africa for many years, attitudes toward same-sex relations were considered more tolerant than in Europe. However, from the 19th to the 20th century, European intellectuals and Christian missionaries entered the region. Under their influence, hostility toward homosexuality intensified. These sentiments became closely linked with religion and have persisted across generations. As a result, strict attitudes toward LGBTQ people remain deeply rooted in both law and society across Africa.

A tomb in Egypt around 2400 BCE where two men were buried embracing (Photo: Jon Bodswort / Wikimedia Commons [Cc-zero])

Liberalization since the 1990s

Although anti-LGBTQ sentiment intensified in Africa under the influence of colonization and Christianity and Islam, some countries saw a change in the 1990s. Until 1992, same-sex conduct was considered a crime in 39 countries. Among them, Guinea-Bissau was the first in Africa to legalize same-sex conduct. In 1993, Guinea-Bissau partially repealed its Portuguese colonial penal code and abolished provisions penalizing “vices against nature,” including homosexuality.

In South Africa, the end of apartheid led to explicit constitutional protections: the 1993 Interim Constitution and the 1996 Constitution enshrined a prohibition on discrimination based on sexual orientation—the first such instance in the world. However, statutes criminalizing same-sex conduct remained for a time, so in 1998 a court ruling affirmed same-sex relations, making same-sex conduct fully legal. Beyond decriminalization, same-sex marriage and adoption by same-sex couples are recognized, creating an environment where many rights can be exercised.

South Africa also allows changes to legal gender on civil records with a medical diagnosis. Transgender people can thus have their gender identity officially recognized.

From the 2000s to the present, 10 countries—Cabo Verde, Lesotho, São Tomé and Príncipe, Mozambique, Seychelles, Botswana, Gabon, Angola, Mauritius, and Namibia—have legalized same-sex conduct.

A Pride event in South Africa (Photo: South African Tourism / Flickr [CC BY 2.0 ])

Countries newly tightening repression

At the same time, some countries are newly imposing restrictions on LGBTQ people’s rights. Burundi had no provision on same-sex conduct, but the 2009 penal code made it illegal. A 2011 order from the Ministry of Education also allows expulsion from middle school on the grounds of “homosexuality.” Similarly, in 2017 Chad made same-sex conduct illegal, toughening treatment of LGBTQ people. Before 2017, Chad’s laws did not clearly address same-sex conduct, but revisions to the penal code criminalized it.

Between 2023 and 2024, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali announced plans to criminalize same-sex conduct, reportedly following coups that brought military governments to power. In Niger and Burkina Faso the change remains declarative and same-sex conduct is still legal, but in Mali a new penal code took effect in December 2024 that made same-sex conduct illegal, making Mali the latest country to criminalize it.

There are also cases where countries that already had anti-LGBTQ policies intensified repression. In 2023, Uganda passed one of Africa’s harsher anti-LGBTQ laws. Same-sex conduct had long been illegal, but the new law further restricts the rights of LGBTQ people. The law criminalizes not only same-sex conduct but also the promotion of homosexuality. Repeat offenses and same-sex conduct with a person living with HIV are deemed “aggravated homosexuality,” for which the death penalty is stipulated. Such treatment can extend beyond homosexual people: other sexual minorities may face the possibility of life imprisonment if their identity becomes known.

In 2024, Ghana also passed a bill targeting LGBTQ people. If the president signs it, not only LGBTQ people but those who support them could be punished. Specifically, people who post about LGBTQ issues on social media platforms or participate in movements defending LGBTQ people could be targeted. The bill also encourages reporting LGBTQ people to authorities, leading some community members and supporters to fear denunciations and consider going into hiding.

LGBTQ people gathered at court when the bid to legalize same-sex conduct was rejected (Kenya) (Photo: Andrew Ngea / Shutterstock.com)

A similar trend is seen in Kenya and Tanzania. Kenya is considering a Family Protection Bill. If enacted, owners of facilities used for same-sex conduct would also be fined. In Tanzania, life imprisonment is currently prescribed for same-sex conduct, and even harsher penalties are being considered.

U.S. Christian conservative groups are partly involved in this trend. Through funding and policy advocacy in Africa, these groups fuel anti-LGBTQ sentiment. They have had international influence since the 2000s, engaging in countries such as Uganda, Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, and South Africa. Over 20 such groups exist and have spent more than USD 54 million on anti-LGBTQ activities since 2007, according to a report. These funds flow to African religious organizations and are used in anti-LGBTQ efforts.

The group Family Watch International (FWI) reportedly supported Ugandan lawmakers who advanced anti-LGBTQ legislation and helped revise the draft bill. The organization denies this, but if true, it would amount to direct influence on policy. FWI values “the family formed by marriage between a man and a woman” and claims that being LGBTQ is due to mental illness or trauma.

Furthermore, some say anti-LGBTQ sentiment is being used politically. In fact, activists in Tanzania point out that politicians criticize LGBTQ people to distract from economic and social problems and gain support.

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni (Photo: Paul Kagam / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Persecution faced by LGBTQ people

As noted, in many African countries the rights of LGBTQ people are restricted by law, but persecution occurs regardless of specific laws. Public opinion appears to play a role. According to Equaldex, a database of LGBTQ-related information, the public opinion index (※8) toward LGBTQ people in Africa is relatively low, and a significant number of people hold negative views. What forms does persecution take in this environment?

First, people can face violent victimization because they are LGBTQ. Beyond the risk of detention or the death penalty under the law, they may be targeted with violence by the state or armed groups, and such violence is often underreported. In countries with anti-LGBTQ policies, groups perpetrating violence sometimes style themselves as vigilantes and justify it. Such violence is seen even in countries where same-sex conduct is legal. In Angola, where same-sex conduct has been legalized, local groups reported LGBTQ people facing violence. Some are forced to live in safe houses to escape violence and arrest.

LGBTQ people also face discrimination in many settings. Discrimination occurs not only in countries with anti-LGBTQ policies but widely in education, healthcare, and workplaces. Even in relatively tolerant South Africa, 56% of LGBTQ respondents reported experiencing discrimination in educational institutions, according to a report. In Uganda, there are cases where bribes were required to obtain medical care. Laws prohibiting such discrimination are few, and South Africa is the only country with explicit constitutional protection. Moreover, misinformation about LGBTQ people is often spread by media and politicians, which reinforces prejudice and discrimination.

Restrictions on freedom of expression are also a major issue. In some countries, publishing, organizing, and holding events related to LGBTQ topics are banned. In Kenya it is illegal to view any film with LGBTQ content, affecting not only LGBTQ people but many others. Elsewhere, participants in Pride events (※9) have been arrested, and the registration of support organizations is obstructed, posing major hurdles to advancing LGBTQ rights.

A poster on a Ugandan school gate explaining risks associated with same-sex conduct: Erich Karnberger / Shutterstock.com)

Discrimination and prejudice against LGBTQ people also affect treatment for HIV/AIDS (※10). Among LGBTQ people, men who have sex with men (MSM) are at a 26-times higher risk of HIV infection due to sexual behavior and require particular attention to HIV. Prejudice against LGBTQ people can make them reluctant to seek sexual health care services. Research also shows that in countries where same-sex conduct is illegal, HIV prevalence is higher than in countries where it is not criminalized. Because HIV/AIDS can be managed with appropriate testing and treatment, ensuring that MSM can access care is crucial.

Human rights activism

While there is generally a strict attitude toward LGBTQ people in Africa, various groups are working to improve LGBTQ rights. For example, in 2022 students in Kenya held a peaceful protest to secure educational rights for LGBTQ students, resulting in a meeting with education ministry leaders. LGBTQ support groups are also active in other social movements. In 2020, Nigeria saw the #EndSars movement (※11), protesting police violence. While participating in #EndSars, LGBTQ people also held protests to advance their own rights. This became a turning point for Nigerian activists to assert their legitimate rights.

Such activism has taken place in the past as well. In the 1980s, protests led by LGBTQ activists ran alongside the anti-apartheid movement struggle. Simon Nkoli, both an anti-apartheid activist and an LGBTQ activist, joined the anti-apartheid struggle in the 1970s and 1980s without hiding his sexual orientation. Inspired by his stance, LGBTQ support groups around the world supported anti-apartheid activities. He also represented various LGBTQ organizations and advocated for decriminalization in South Africa.

Today, some young people are at the forefront of these movements, fighting to improve LGBTQ rights. For example, initiatives to provide safe houses for persecuted LGBTQ people activities and to offer options for asylum and migration programs are being led by people in their 20s.

Exhibit of Black LGBTQ people asserting their rights in the anti-apartheid struggle: LennyFlank / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

Conclusion

Compared with other regions, LGBTQ people’s rights are often more restricted in Africa, and public opinion is not particularly positive. Some countries are strengthening anti-LGBTQ policies. People face various forms of persecution simply for being “LGBTQ.” Will this situation improve in the future? As described in this article, anti-LGBTQ sentiment in Africa dates back to the colonial era and is closely intertwined with religion and politics. It may be difficult to change these sentiments at their root.

At the same time, there are countries and leaders working to improve LGBTQ rights, and many activists are fighting for their rights amid repression. Such actions may lead to shifts in public attitudes and policy. Anti-LGBTQ sentiment in Africa is also influenced by other countries. Therefore, it is important for the world at large—not just Africa—to recognize the current situation. We hope that this movement spreads and that a day will come when LGBTQ people living in Africa can live freely.

※1 LGBTQ is an acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (those who do not fix their sexual orientation or gender identity) or queer (sexual minorities broadly). It is used as a collective term for sexual minorities.

※2 The African Union holds that Africa comprises 55 countries. However, as most of Western Sahara is occupied by Morocco and it is not a UN member state, some sources count 54 countries.

※3 It has been announced that since 1987 Mauritania has observed a moratorium on applying the death penalty. However, the possibility of the death penalty remains.

※4 Non-binary refers to people who do not identify themselves within the male/female gender binary.

※5 Intersex generally refers to people born with genitalia or sex characteristics that do not fit typical definitions of male or female.

※6 The countries marked unknown are Egypt and Western Sahara. In Egypt, while same-sex conduct is not explicitly criminalized, the state effectively criminalizes homosexuality and may use morality provisions to prosecute LGBTQ people. In Western Sahara, the situation varies by area: in Moroccan-occupied regions it is considered illegal as in Morocco, while in areas governed by the Polisario Front, it is unclear whether criminalization of same-sex conduct is codified.

※7 There is also a theory that the two men buried and depicted on the tomb’s wall paintings were brothers.

※8 According to Equaldex, the public opinion index measures attitudes toward LGBTQ issues using reliable surveys. For example, if in a survey asking “Do you support same-sex marriage?” 56% answered “support,” the number 56 is used. The index is the average of all such values revealed by surveys.

※9 Pride is a celebration of advances in LGBTQ people’s rights and a wish for further progress, and events related to it are called Pride events.

※10 HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) is a virus that damages the human immune system. AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) is a late stage of HIV infection. Once AIDS develops, people become more susceptible to various pathogens and diseases.

※11 #EndSars activities refer to a movement that began in 2020 calling for the abolition of the Nigerian police’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad (Sars). It grew after videos of alleged Sars human rights abuses spread.

Writer: Ayaka Takeuchi

Graphics: MIKI Yuna

サブサハラアフリカ地域でのLGBTQの現状に、植民地主義の歴史が関わっているということを知り、驚きと同時に植民地主義の爪痕の深さを改めて考えることができました。

1日も早く、サブサハラアフリカ地域を含めて世界中のLGBTQの権利回復が実現することを願うばかりです️️

キリスト教徒が多いから、イスラム教徒が多いからと、宗教のせいにできそうかと思いきや、これまでの歴史の形成によってLGBTQに対する嫌悪感や厳格な法制度ができあがったんですね。そういった観点でも、一国の法制度や特定の人や思想への嫌悪感がどのように醸成されていったかを知ることは大切ですね。

宗教の影響力や文化的な影響力よりも、法律の影響力が強くなっていると分かる記事でした。逆に法律が、LGBTQの権利を認めれば、社会もそれを受け入れるようになるかもしれませんね。