From 2021 to 2022, Morocco severed diplomatic relations with Algeria and recalled its ambassadors from Spain and Tunisia, creating friction with various neighboring countries. The background to these tensions is the Western Sahara issue.

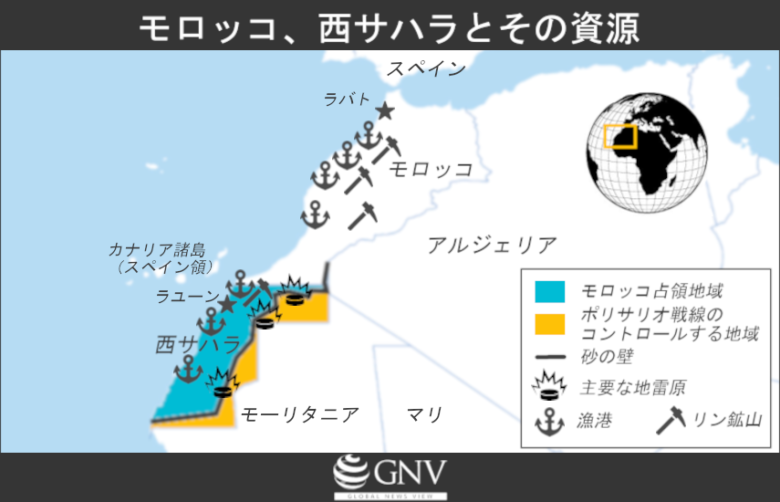

Western Sahara is a region in northwestern Africa considered the largest colony in Africa (Note 1), and Morocco currently occupies about 80% of its territory. While the African Union (AU) recognizes Western Sahara as a member state, the United Nations does not, making Western Sahara a “region that is like a state but not a state.”

Until 1975 this region was a Spanish colony. After Spain’s withdrawal, Morocco, which invaded, and the Polisario Front seeking Western Saharan independence each claimed sovereignty, and armed conflict broke out between them. A ceasefire agreement was reached in 1991 and held for years, but in 2020 the ceasefire was abandoned and the conflict resumed. What exactly is happening in Western Sahara, where tensions have risen alongside the resumption of hostilities? This article explores the background to the conflict and the current situation, including the international relations surrounding Western Sahara.

A Polisario Front base in the Western Sahara region (Photo: Teresa Marín / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

What is the Western Sahara conflict?

Western Sahara has a population of about 612,000 and an area of about 266,000 square kilometers. Historically, various ethnic groups lived in what is now Western Sahara, and the region was part of Saharan trade networks. There was no central government ruling the entire area, and until it became a Spanish colony in 1884, it appears it was not under direct rule. After colonization, the region became known as “Spanish Sahara.”

In the 1960s most African countries gained independence, but Spain, then a dictatorship, did not intend to relinquish its colonies. As criticism from the UN General Assembly and others mounted, in 1963 Morocco and Mauritania each claimed sovereignty over Western Sahara. In 1973, Western Sahara’s residents formed the Polisario Front to seek independence and launched a movement.

Backed by Algeria, the Polisario Front resisted Spain, effectively ending Spanish control in Western Sahara. In 1974, Spanish authorities announced a referendum on Western Saharan independence. Believing that such a vote would likely produce an independent Sahrawi state, Morocco filed a case with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) asserting its sovereignty over Western Sahara. However, in 1975 the ICJ issued an advisory opinion concluding that neither Morocco nor Mauritania possessed sovereignty over Western Sahara.

Even so, Morocco did not soften its claims. It continued pressuring Spain, including by organizing the “Green March,” sending some 350,000 of its citizens across the border to settle in Western Sahara. Under this pressure, in 1975 Spain secretly agreed with Morocco and Mauritania to unilaterally divide Western Sahara between the two countries. As a result, Morocco and Mauritania invaded and occupied Western Sahara in violation of international law. Such occupation disregarded the Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination.

The Polisario Front resisted the two countries’ occupation, and in 1976 armed conflict broke out between the Polisario Front and Morocco–Mauritania. That same year the Polisario Front, operating from southwestern Algeria near the border, proclaimed the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) as the legitimate representative of Sahrawis seeking independence. Algeria not only provided bases but also military training and weapons, continuing to support the Polisario Front.

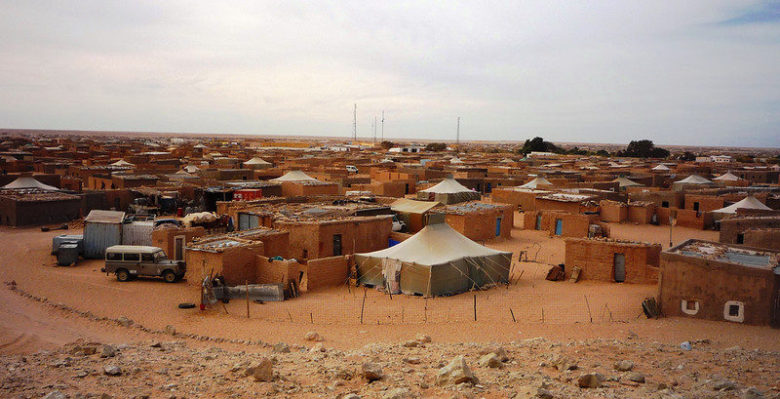

Refugee camp in southwestern Algeria (Photo: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Subsequently, the Polisario Front concluded a ceasefire with Mauritania, and in 1979 Mauritania renounced its claim to Western Sahara. Morocco then annexed that area as well, intensifying its confrontation with the Polisario Front. France and the United States, primarily to counter Algeria—which had close ties to the Soviet Union during the Cold War—provided military support to Morocco. With this backing, Morocco occupied about 80% of Western Sahara. To escape Morocco’s advance, many Sahrawis fled abroad and became refugees. Most went to neighboring Algeria, where there are refugee camps in the southwest housing roughly 200,000 people today.

From 1980 to 1987, Morocco also built a roughly 2,700 km-long “sand wall” separating the areas it occupies from those held by the Polisario Front. Because of this sand wall, about 100,000 Sahrawis remain stranded in Moroccan-occupied territory. Morocco planted vast numbers of landmines around the wall, creating what is believed to be the world’s longest minefield. Moreover, from the outset of the occupation there have been human rights violations primarily against Sahrawis, and communications (mail, telephone) and entry by foreigners have been strictly restricted. Even today, serious abuses are frequently reported, including unjust arrests of pro-independence Sahrawis and human rights advocates and inhumane acts such as torture.

Relations with international organizations

In 1991, under UN mediation, the Polisario Front and Morocco announced a ceasefire and agreed to hold a referendum to decide whether Western Sahara would become independent or be integrated into Morocco. However, because many Moroccans had already moved into Western Sahara through actions such as the Green March, Morocco opposed a referendum structured to exclude these Moroccans’ voting rights, and to this day no referendum has been held. Morocco’s continued obstruction is driven in part by a desire to avoid losing control over de facto occupied territory. Another motive is securing Western Sahara’s abundant resources. The region has rich fisheries and phosphate deposits; together, Morocco’s and Western Sahara’s phosphate reserves are said to account for about 72% of global reserves. Because Morocco profits from exploiting these resources, it is loath to relinquish Western Sahara.

Phosphate deposit in Western Sahara (Photo: jbdodane / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Debate over who should be eligible to vote has dragged on for years. In 2007, as an alternative to a referendum, Morocco proposed an autonomy plan under which SADR would enjoy autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty. In essence, however, this amounts to Morocco’s integration and absorption of Western Sahara, and no agreement has been reached.

The UN General Assembly does not recognize Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara and affirms the Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination and independence. To implement a referendum, the UN Security Council established the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) in 1991, sending envoys to seek compromises. As noted, however, negotiations to realize a referendum are effectively deadlocked, and MINURSO has not achieved major results. One potential solution would be for the UN envoy to exercise strong political leadership to push the referendum forward. Yet France and the United States, both veto-wielding Council members, have blocked efforts to advance the vote as part of their support for Morocco, making this unlikely.

Meanwhile, although the General Assembly affirms the Sahrawi right to self-determination and independence, Western Sahara is not recognized as a UN member state. Membership requires a Security Council recommendation followed by a General Assembly vote. Given France’s and the United States’ support for Morocco and veto power in the Council, Western Sahara’s admission appears extremely difficult.

Official talks between the SADR and South Africa (Photo: GovernmentZA / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

In contrast to the General Assembly’s and Security Council’s positions, the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor to the AU, recognized Western Sahara (SADR) as a sovereign state and admitted it in 1982. Including the OAU era, the AU has been Western Sahara’s strongest base of support. Morocco protested and withdrew from the OAU in 1984. In 2016, however, Morocco reversed course and applied to rejoin the AU, and in 2017 the AU approved its return. Morocco likely judged it necessary to build good relations with African states to garner international support for its claim that Western Sahara is Moroccan territory—hence its decision to rejoin even though the AU supports SADR—among other possible reasons.

Other countries’ positions on the Western Sahara issue

Among AU members, Algeria is the strongest supporter of SADR. Algeria has long clashed with Morocco over territorial issues and Cold War alignments, and it supports SADR, which also opposes Morocco. Even though Morocco controls roughly 80% of Western Sahara, the Polisario Front can still resist in large part because Algeria provides bases and military support. Algeria has also engaged in lobbying other states to recognize SADR. As noted, Algeria hosts refugee camps created by Morocco’s invasion, and around about 200,000 people—roughly twice as many as those stranded in Moroccan-occupied territory—live there.

Conversely, countries that, via Morocco, benefit from Western Sahara’s abundant fisheries and mineral resources effectively tolerate Morocco’s occupation and help enable its exploitation. In fact, in 2002 the UN Legal Counsel issued an opinion that economic activities in occupied Western Sahara that do not take Sahrawi interests into account violate international law. Regarding fisheries, Japan and the United States are notable. Japan is Morocco’s largest trading partner for products like octopus, relying on Morocco for about 30% of its imported frozen octopus. Western Sahara’s waters are well known as an octopus fishing ground, and it is natural that many imported octopus were caught there. Yet the packages on Japanese store shelves are labeled only as “Product of Morocco.”

Fish market in Dakhla, Western Sahara (Photo: David Stanley / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

For the phosphate trade that Morocco exploits from Western Sahara, India and New Zealand stand out. Following the 2002 UN Legal Counsel opinion, a global movement grew against illegal extraction in Western Sahara, and many foreign firms have stopped trading phosphates with Moroccan companies. However, companies in India and New Zealand have continued such transactions and continue importing phosphates from Western Sahara.

The European Union (EU) in 2000 brought into force with Morocco an Association Agreement aiming toward future free trade (FTA). Since then the EU and Morocco have strengthened ties through multiple agreements on fisheries and trade. Under these agreements, EU countries, the United Kingdom, and multinationals based there have developed economic interests with Morocco that amount to exploiting Western Sahara’s resources. Among EU states, France is Morocco’s largest trading partner and has deep ties in politics and economics rooted in its past colonial rule. Spain is also one of Morocco’s major trading partners, and as neighbors they are historically and economically closely linked.

One reason EU countries seek friendly relations with Morocco is the issue of migrant and refugee flows from Africa. Morocco is one of the transit routes from Africa to Europe; if relations sour, Morocco—which usually strictly limits these flows—might relax controls and tolerate crossings, an outcome EU states want to avoid. A second reason is that Morocco has long cooperated with EU countries on counterterrorism, including information sharing.

At the same time, through the European Commission’s Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO), the EU has repeatedly stated its official position supporting UN efforts to resolve the issue. Since 2016, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) has issued multiple rulings that agreements between the EU and Morocco do not apply to Western Sahara. As a result of these rulings, EU fishing vessels are prohibited from operating off Western Sahara. While governments such as Japan and the United States have not imposed similar restrictions, the ECJ rulings are significant in curbing resource exploitation in Western Sahara. Following the rulings, Morocco effectively froze counterterrorism cooperation with EU countries. How EU states position themselves on Western Sahara going forward bears watching.

MINURSO staff monitoring the ceasefire in Western Sahara (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The United States is another long-time supporter of Morocco. From the perspective of its global strategy, the U.S. sees Morocco’s position on the Strait of Gibraltar as important. During the Cold War, it strengthened ties through an alliance and provided military support to Morocco. In 2020, under the Donald Trump administration, the U.S. concluded the Abraham Accords, under which the U.S. recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in exchange for Morocco’s normalization of relations with Israel. The current Joe Biden administration has maintained this policy. At the same time, there are voices in U.S. politics critical of the occupation (Note 2), including calls to change the venue of the U.S.-hosted annual multilateral military exercise from Morocco.

Although we just cited Spain as leaning toward Morocco, as Western Sahara’s former colonial power it had taken a comparatively neutral stance. When the U.S. recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in 2020, Spain explicitly criticized Washington and, that same year, allowed Polisario leader Brahim Ghali—infected with COVID-19—to be treated at a Spanish hospital. Morocco reacted angrily to these moves. In 2021, Morocco expressed displeasure at Spain’s actions and recalled its ambassador. That same year, Morocco, in effect, tolerated the entry of roughly 8,000 migrants from its territory into the Spanish enclave of Ceuta (Note 3), putting diplomatic pressure on Spain. This use of migration as leverage is reminiscent of the 1975 “Green March.”

Under Moroccan pressure, Spain in 2021 issued a statement supporting Morocco’s autonomy proposal for Western Sahara, shifting to a more pro-Moroccan stance. Spain’s move not only to tolerate but to formally endorse Morocco’s control greatly unsettled SADR and Algeria. Algeria’s backlash was particularly strong: in 2021 it announced it would not renew a gas pipeline contract sending natural gas to Spain via Morocco, hinting at a potential halt to gas exports. In 2022, Algeria went further by suspending foreign trade in goods and services with Spain, worsening bilateral relations.

Resurgence of the conflict

In 2020, Western Saharan independence activists blocked the road linking Western Sahara and Mauritania in the buffer zone. In response, Moroccan forces conducted an operation to forcibly remove the civilians. Although there were no casualties or arrests, the Polisario Front declared the abrogation of the 1991 ceasefire, claiming that Morocco’s military operation itself violated the agreement.

Polisario Front troops (Photo: Western Sahara / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

The Polisario Front resumed armed resistance, and in 2021 an incident involving Polisario attacks reportedly left 6 Moroccan personnel dead—signs that the armed conflict may further escalate. One factor pushing the Polisario toward armed struggle is that the UN-led peace plan has been effectively nonfunctional for more than 30 years since 1991, fueling Sahrawi frustration. Many Polisario members—some of whom have never lived in Western Sahara—are increasingly motivated to resort to force under the banner of “reclaiming the homeland.”

The conflict’s resurgence has also worsened Morocco–Algeria relations. Citing hostile Moroccan actions in addition to Western Sahara–related friction, Algeria announced in 2021 that it would sever diplomatic ties with Morocco. That same year, Algeria also banned Moroccan aircraft from its airspace. After the break, relations deteriorated further, including an incident in which 3 Algerians were killed by Moroccan forces in Polisario-held Western Sahara.

Toward a resolution

In recent years, armed conflict has resumed in Western Sahara. If the issue remains unresolved, the Western Sahara conflict could escalate into a larger war. Both the Moroccan and Algerian governments face domestic challenges such as rising unemployment, corruption, and sluggish economies, and there is concern that they are exploiting the Western Sahara confrontation to divert public attention abroad—a further problem.

To advance a settlement, in 2021 the UN Security Council, through MINURSO, appointed after about 2 years a new UN envoy for Western Sahara, Staffan de Mistura. He previously served as the UN Special Envoy for Syria and has experience working toward conflict resolution. One hopes that de Mistura will lead concrete talks toward restoring the ceasefire.

However, with many high-income countries and companies based in them pursuing political and economic interests through cooperation with Morocco on trade and security, the UN envoy’s political leverage is limited. To push these governments and firms toward concrete steps for a peaceful resolution, it may be key for more people, as citizens and consumers, to learn about the issue and take actions that encourage progress.

Today, Western Sahara faces not only a longstanding sovereignty dispute but also frequent reports of military clashes causing casualties and serious human rights abuses by Moroccan authorities. To protect the lives and safety of many people, urgent efforts toward a solution are needed.

Note 1: While accounts vary, there are still regions in Africa that have yet to complete decolonization. For details, see: “A ‘Europe’ that is not Europe.”

Note 2: Senator James Inhofe, a strong opponent of Morocco’s occupation within the U.S., pressed the Department of Defense to exclude Morocco as a host for military exercises, and the Pentagon is considering this. Reflecting such domestic opposition to Morocco’s occupation of Western Sahara, in 2022 the U.S. Senate added a provision to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) barring U.S. participation in multilateral exercises held in Morocco unless the U.S. government commits to encouraging a mutually acceptable political solution between Morocco and the Polisario Front in Western Sahara.

Note 3: An exclave located near the northern coast of the African continent, now an autonomous city of Spain.

Writer: Seiya Iwata

Graphics: Takumi Kuriyama

0 Comments