In West Africa, security challenges have intensified, primarily due to the rise of extremist armed groups in the Sahel, and civilian governments have been unable to control them. As a result, Mali and Burkina Faso experienced successive coups between 2020 and 2022. Facing similar problems, the military regimes in the two countries forged close ties. Then in July 2023, a military coup also occurred in neighboring Niger.

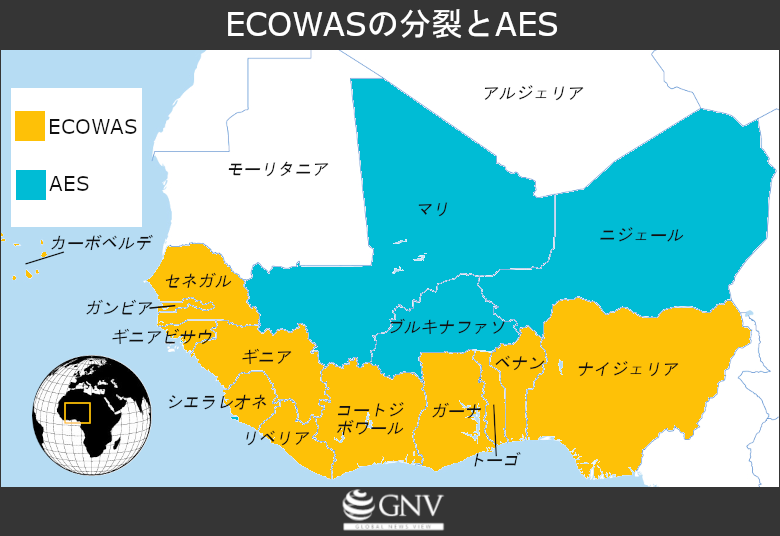

ECOWAS, of which these three countries were members, convened an extraordinary summit and condemned the coup. Furthermore, ECOWAS hinted at the possibility of a military intervention to free the deposed President Mohamed Bazoum and restore democracy. In response, the governments of Burkina Faso and Mali issued a joint statement declaring that any attack targeting the Nigerien authorities would be interpreted as a “declaration of war” against them. In September 2023, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger formed their own organization, the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), and in January 2024 announced their withdrawal from ECOWAS. Since then, the two organizations have been vying for diplomatic leadership.

This article explains the relationship between these two institutions—ECOWAS and the AES—and what lies ahead for West Africa.

目次

Origins and objectives of ECOWAS

ECOWAS was established in May 1975 in Lagos, Nigeria, initially as an economic group. It comprises 15 countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Senegal, and Togo. The member states of ECOWAS have a combined population of 300 million, a gross domestic product (GDP) of USD 734.8 billion, and a territory covering 5 million square kilometers.

ECOWAS’s original aim was to coordinate, strengthen, and achieve economic integration among member states. In the 1990s, its functions expanded to political issues. Thus, today’s ECOWAS upholds basic principles such as a pledge of non-aggression among member states, the promotion and strengthening of democratic governance, and the maintenance of peace, stability, and security in the region. These are the foundational principles designed to enable the peaceful resolution of disputes and preserve calm in the region.

ECOWAS and security issues

Since the 1990s, ECOWAS member states facing armed conflict have also been subject to military interventions. The ECOWAS Monitoring Group (ECOMOG), the bloc’s military arm, intervened in Liberia (1990), Sierra Leone (1997), Guinea-Bissau (1999), and Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia (2003). In 2013, ECOWAS deployed troops under the African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA). AFISMA’s mandate was to support the Malian government against insurgents expanding their influence in northern Mali. AFISMA was later taken over by the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). ECOWAS’s most recent deployment was in The Gambia in 2017, during “Operation Restore Democracy” following an electoral dispute.

In addition to armed conflicts, the region has seen both military coups and constitutional coups—when an incumbent president changes constitutional term limits (usually two terms) to extend their tenure. In dealing with military coups, ECOWAS typically suspends the country’s membership and imposes economic sanctions. Against Mali (2020), Guinea (2021), and Burkina Faso (2022), ECOWAS imposed sanctions and suspended their membership. ECOWAS also supports transitional authorities to return power to civilians.

ECOWAS countries training with U.S. soldiers (Photo: U.S. Army Southern European Task Force / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

The beginnings of the AES

In Mali, despite MINUSMA as well as French (Operation Barkhane) and European military interventions (the Takuba Task Force), the conflict has persisted. For years, multiple armed groups—mainly Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS)—have continued to exert influence across Mali. Since 2015, the violence by these groups has spread into Burkina Faso and Niger. The most intense fighting has occurred in the Liptako–Gourma area, the vast, hard-to-secure tri-border zone where the three countries meet.

The background to the conflicts affecting Mali and its two neighbors is complex, originating in a separatist movement in northern Mali led largely by Tuareg groups, which was later joined by regional extremist organizations. Other key factors include land disputes between settled farmers and pastoralists, and the failure of governments to provide essential public services to impoverished communities in the arid periphery. The coups in Mali (August 2020 and May 2021) and Burkina Faso (January and September 2022) stem from the instability generated by these armed groups and the failure of leaders to contain them.

In just three years, there were five coups among ECOWAS member states: two in Mali (2020 and 2021), one in Guinea (2021), and two in Burkina Faso (both in 2022). The subsequent 2023 coup in Niger was a decisive blow for ECOWAS. While the bloc imposed economic sanctions on Mali, Guinea, and Burkina Faso in the Sahel, it took an even tougher stance in Niger. Beyond the usual economic sanctions, it warned that it would take military action to free President Bazoum and restore constitutional rule. This hard line appeared aimed at preventing the post-coup junta in Niger from consolidating power and deterring others. Before any intervention, ECOWAS dispatched negotiators while calling on the Nigerien junta to step down.

The French government voiced support for a military intervention to stop the coup in Niger immediately. That support reflected multiple motives. French companies account for much of Niger’s uranium production, giving France significant economic and energy interests there. Paris also had concerns that the coup could suspend defense agreements with Niger and force the withdrawal of French troops stationed there.

Training of Nigerien forces (2018) (Photo: US Africa Command / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

In this context, ECOWAS’s hard line was widely interpreted as being under European influence. The intervention plan provoked a backlash from the military regimes in Burkina Faso and Mali, which issued a joint statement warning that “any military intervention against Niger would amount to a declaration of war against us.” They also insisted they would not impose “illegal, unjust and inhumane sanctions” on the people and authorities of Niger.

Beyond their shared history of French colonial rule, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have been bound together by the tri-border zone known as Liptako–Gourma and by the numerous attacks carried out there by armed groups since 2013. Together with Mauritania and Chad, they had also engaged in military cooperation through the G5 Sahel, launched in 2014 with the stated aims of fostering economic development and improving security. As instability deepened, a G5 Sahel Joint Force was created in 2017. However, dissatisfied with France’s heavy influence, Mali in 2022 and Burkina Faso and Niger in 2023 withdrew.

The offer by the governments of Burkina Faso and Mali to provide military support to Niger caught ECOWAS off guard. It also paved the way for the conception and establishment of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), finalized on September 16, 2023, when the three countries signed the Liptako–Gourma Charter. The alliance’s main purpose is collective self-defense, requiring members to provide military assistance to one another in the event of armed conflict or external aggression, as stipulated. Any attack threatening a member’s sovereignty or territorial integrity is considered an attack on all.

Moreover, at a summit held in July 2024 in Niamey, the Nigerien capital, the AES was further expanded into a Sahel Confederation (retaining the acronym AES).

The leaders of the military regimes: Goïta (Mali), Traoré (Burkina Faso), and Tchiani (Niger) (Photo: President of Russia [CC BY 4.0], Lamine Traoré / VOA [Public domain], Office of Radio and Television of Niger [Fair use] / Wikimedia Commons)

AES decisions and plans

The AES began by helping Niger survive ECOWAS’s economic sanctions, strengthening coordination, and diversifying external partnerships away from ECOWAS—including military cooperation with Russia. Mali and Burkina Faso, AES members, had already started military cooperation with Russia in 2021 and 2022. Following them, Niger abandoned its defense agreements with France and asked the United States to withdraw its troops. Niger also left the G5 Sahel Joint Force and began military cooperation with Russia. In January 2024, the AES countries announced that they had decided to leave ECOWAS, describing ECOWAS’s sanctions on Niger as a tool of European—particularly French—power.

The AES’s new partners include Russia, China, North Korea, and Turkey. Russia contends that European countries have refused to supply the weapons needed to fight insurgents and extremists and secure shared territory, and has become a major supplier of heavy arms to these states. In addition to its growing presence in Mali, Russia has sent personnel to Burkina Faso and Niger to provide military training. Turkey is a key supplier of drones. The AES maintains that these military agreements, unlike those with France and the United States, are based on neutral understandings and mutual benefits. For AES leaders, the freedom to build diverse partnerships is seen as proof of sovereignty and independence under the current regimes.

Alongside diversification, in March 2024 the AES announced the creation of a joint force to fight insurgents and address their own security challenges. So far, however, it is difficult to assess the AES’s fight against armed groups. In November 2023, they reported retaking the northern Malian town of Kidal from Tuareg separatist groups, hailing a victory for the junta. Yet terrorist attacks continue in large numbers.

These attacks have been criticized as reflecting the region’s instability and the shortcomings of the new organization’s approach. Human rights abuses by the juntas have also drawn criticism. In response, in July 2024 the AES launched a project to build a social media campaign and a web TV platform to counter what it calls “organized disinformation” targeting the alliance—seeking to stoke citizens’ loyalty to their governments and enhance the AES’s international reputation. Beyond confronting armed groups, it also aims to prevail in an “information war” with other countries through the promotion of “patriotic journalism.”

Islamist militants near the Mali–Niger border (Photo: saharan kotogo / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

By evolving from an alliance into a confederation, the AES seeks to unite 72 million people into a single community. This change will enable the free movement of goods and people among the three countries. Its long-term objective is eventually to transition to a federation that transcends individual national identities. In that federation, citizens of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger would be known as “citizens of the AES,” and administrative obstacles would be removed.

As a step toward this integration, Mali’s President Assimi Goïta announced the launch of biometric passports across the area to simplify travel within and beyond the AES region. At the same time, the three countries said they would work together to expand transport and communications infrastructure, liberalize trade and the movement of goods and people, and invest in the agriculture, mining, and energy sectors for industrial reform.

The three countries already appear to be deepening cooperation. In February 2024, Niger agreed to sell Mali 150 million liters of diesel at nearly half the international price, a major boost for Mali, which frequently faces energy shortages. Burkina Faso is also benefiting from Niger’s petroleum.

Additionally, in July 2024 the AES announced it would coordinate diplomatic initiatives and establish an investment bank and a stabilization fund. Before this announcement, social media frequently buzzed with rumors that the AES would introduce a single currency, the “Sahel,” to replace the CFA franc. Given France’s heavy influence, the CFA franc is widely seen in the region as a colonial currency. If a new currency were introduced, the AES would take a groundbreaking step toward financial and economic independence from France and further boost public trust.

Near the Benin–Niger border (Photo: NigerTZai / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Where the two organizations stand now

The coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger created tense relations in the region. The first clash arose when Burkina Faso and Mali rejected ECOWAS sanctions against Niger and backed its authorities. The establishment of the AES followed, and in January 2024 its members announced their intent to leave ECOWAS. Since then, attempts to reconcile the old West African bloc and its breakaway members have repeatedly failed. In February, ECOWAS urged Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali to reconsider their withdrawal from the political and economic union and warned of the hardship the move would impose on their populations.

However, the AES has not suffered further hardship. First, because the military coups in the three countries enjoyed broad domestic support, the sanctions had little effect. The assumption was that economic difficulties would turn the public against coup leaders and force the plotters to relinquish power. Instead, the sanctions did not have that effect and rather increased negative views of ECOWAS. Many in the AES see ECOWAS not as a “people’s ECOWAS” but as an “ECOWAS of heads of state,” backed by Western powers to strengthen political power and influence.

The new juntas also received support from Russia in various fields after taking power. Moreover, although being cut off from ECOWAS risked depriving the three landlocked countries of access to the sea, they benefited from the involvement of new players such as Morocco, which offered them access to the Atlantic. ECOWAS sanctions and threats thus became a catalyst for acquiring new partners.

In response, ECOWAS lifted sanctions and reopened borders with Niger. It also appointed Senegal’s newly elected president, Bassirou Diomaye Faye, as mediator. However, AES leaders have not reversed their decision to leave, stressing that “turning our backs on ECOWAS is definitive.” In this way, West Africa has been split into two blocs.

Delegates discuss the situations in Guinea and Mali at an ECOWAS meeting (2022) (Photo: Présidence de la République du Bénin / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The emergence of two blocs in today’s West Africa recalls the Cold War era, when the world was divided into East and West. Now, the AES confederation has Eastern partners, while ECOWAS has Western partners. AES governments are trying to maintain their legitimacy and claim that Western powers have used ECOWAS countries to destabilize them. The main point of contention appears to be the choice of international partners.

However, the division is not foreordained. A year after its launch, the AES is moving toward a split from ECOWAS, but the three countries say they want to maintain good relations with neighbors through bilateral agreements. Despite their differences, the AES is not necessarily an anti-ECOWAS organization. And ECOWAS has not stopped trying to negotiate with the AES, ideally aiming for reintegration or for the AES to exist as a member within ECOWAS. For now, however, the outlook remains uncertain.

Writer: Gaius Ilboudo

Translation: Kyoka Wada

Graphics: MIKI Yuna

So informative !

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.