Have you heard the term FGM (Female Genital Mutilation), which refers to the cutting or injury of female genitalia? It has been practiced for a long time as a traditional custom in many countries, but it places a heavy burden on women and there are said to be no health benefits. In recent years, FGM has plummeted, mainly across Africa. In East Africa, a study of girls under 14 found that between 1995 and 2016 the prevalence dropped from 71.4% to 8%. What was behind such a dramatic decline? In this article, we take a closer look at FGM and its reduction.

Girls resisting FGM (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

FGM: What is it?

First, an explanation of what FGM is. FGM refers to the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. Injury includes pricking with needles, cauterization, and more. Specifically, there are broadly four patterns.

Because FGM is not based on medical evidence, it places a great burden on women’s bodies. Reported harms include severe bleeding; difficulties with urination, pregnancy, and childbirth; infections such as tetanus; the onset of mental illness; and pain during sexual intercourse, among others. In the worst cases, it can be fatal—making it a life-risking practice for those subjected to it. Based in particular on Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) assert that FGM is a violation of the rights of women and children.

Despite the grave dangers, FGM is believed to have begun as far back as ancient Egypt. It is mainly carried out from infancy to around age 15, and in some cases 2–3 days after birth. It is often performed by local elder women who have not received proper medical training; traditional healers, herbalists, and female relatives may also act as practitioners.

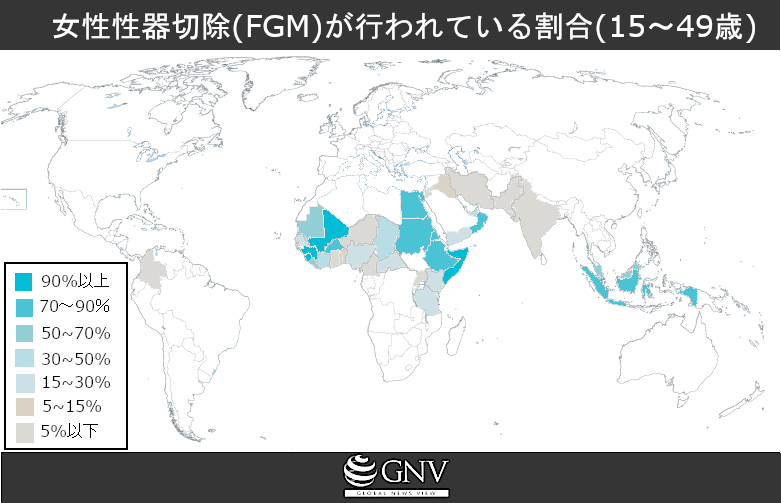

FGM is practiced in about 30 countries worldwide, predominantly in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. At present, at least 200 million women in those countries have undergone FGM, and each day about 6,000 women are said to become newly subjected to it.

As of 2016. Created based on data from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

Why FGM is practiced

Why has FGM—said to offer no benefit to women’s health—continued from ancient Egypt to the present day? There are several reasons. In some cases it is carried out based on male-dominant views that women should remain virgins until marriage and then enter into domestic life, and that women’s independence and assertiveness are undesirable. The purpose of FGM is to suppress women’s sexual urges before and after marriage and to control female sexuality.

As FGM has spread and taken root, it has come to be regarded as a social obligation. In many regions where FGM is practiced, those who do not undergo it are thought unable to marry or be recognized as full adults. FGM is thus treated as an indispensable coming-of-age ceremony for women’s education and preparation for marriage. Moreover, in societies where it is the norm for women to make a living by becoming economically dependent on men through marriage, practicing FGM can become a means for women to survive.

Furthermore, the aspect of controlling female sexuality overlaps with the religious importance placed on virginity; even when a religion does not directly support FGM, its teachings may be used as a basis to justify it. Including such beliefs, in some cases FGM is considered something “pure” or an emblem of “beauty.”

Decline of FGM

Although FGM is practiced in different regions for various reasons, its prevalence has been declining in recent years. A study on FGM prevalence was conducted among 208,195 girls up to age 14 across 29 African countries and two Middle Eastern countries (Iraq and Yemen) from 1990 to 2017. According to the study, East Africa—where the decline was particularly striking—saw a drop from 71.4% to 8% between 1995 and 2016. In addition, North Africa fell from 58% to 14% between 1990 and 2015, and West Africa from 73.6% to 25.4% between 1996 and 2017. All regions saw reductions of over 40% within 10–15 years.

A session on FGM held at the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) in 2018 (Photo: UN Women/Flickr [ CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

However, even within Africa, national prevalence rates vary widely. As the world map above suggests, among women aged 15–49, FGM is almost universal in countries like Somalia, Guinea, and Djibouti with rates over 90%, whereas in Cameroon and Uganda it is around 1%. Given these differences, it is difficult to say that FGM is decreasing at the same rate across Africa. Focusing on the Middle East, prevalence rose by 1% between 1997 and 2013, so we cannot claim that FGM is decreasing uniformly in every region of the world. Nonetheless, the substantial decline in FGM prevalence, particularly in Africa, is highly significant.

Background to the decline of FGM

What lies behind the decline of FGM centered in Africa? We can see the efforts of people from all walks of life.

First, important changes have taken place at the government level, especially through legal measures. Today, in Africa, the practice of FGM is legally prohibited in 22 of the 28 countries where it is carried out. Even so, passing laws banning FGM has not been easy, especially when it means changing long-standing traditions. Consider West Africa. In 1991, Burkina Faso introduced the first law in West Africa to penalize FGM. Other countries followed, with Benin in 2003 and Guinea in 2016 adopting laws prohibiting FGM. Meanwhile in Liberia, as of 2013 about 40% of women aged 15–49 had undergone FGM, yet no law banning it had been enacted for a long time. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who became president in 2006 and advocated for women’s rights, was only able to sign an executive order banning FGM in 2018—12 years after taking office. Following this executive order in Liberia, Mali is now the only country in West Africa that has not abolished FGM.

Former Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (Photo: European Parliament/Flickr [ CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Somalia—a country with high FGM prevalence—is also moving toward abolition. In 2012, FGM was banned under the constitution, but a survey conducted between 2006 and 2011 found that 64.5% of women believed FGM should continue, indicating how deeply rooted it is. Because of the high level of support, lawmakers feared losing votes and had not introduced strong, specific penal provisions against performing FGM. However, after a 10-year-old girl died due to FGM in 2018, the country announced its first prosecution. This is likely to be a major turning point in shifting perceptions in Somalia, where FGM is deeply entrenched.

In regions where FGM is deeply rooted as a tradition, legal bans alone cannot eliminate the practice. It is necessary to persuade even those who believe the custom should continue. In that sense, outreach and persuasion by traditional leaders can be effective. Traditional leaders often command deep trust and operate at a smaller, local scale than national governments, making their views more reflective of and persuasive to public opinion. There are also collaborative efforts among traditional leaders to work toward ending FGM. For example, in August 2018 in Nairobi, Kenya, leaders from 17 African countries held a conference with the aim of taking the outcomes back to their communities and spreading them among the people. They discussed plans to contribute to the African Union’s efforts to end child marriage, FGM, and other harmful cultural practices.

In addition, numerous religious leaders have raised their voices against FGM. For instance, Somali cleric Ibrahim Hassan has stated that FGM is not supported by Islam and is leading a campaign to end it. Religious leaders directly stating that FGM is not religiously endorsed is important for dispelling misunderstandings; rather than laws alone, trusted leaders speaking directly to people can be an effective means of changing attitudes toward FGM.

A study session on FGM held among mothers in Ethiopia (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia/Flickr [ CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

As noted earlier, FGM is a long-standing traditional practice, and because the idea that one is not recognized as a full-fledged woman without undergoing FGM has taken root, abolition and attitude change are not straightforward. Therefore, rather than rejecting everything about FGM, there is growing adoption of new ceremonies that understand and respect the tradition and cultural characteristics and focus on the aspect of an “initiation into adulthood” as an alternative to FGM. These are called alternative rites of passage, or ARP (Alternative Rites of Passage) training. They not only teach girls what FGM is and its dangers, but also provide education about health and culture, aiming to help them make the best choices for their futures. As abolition progresses, the adoption of such ceremonies will likely expand further.

Change is also happening not only among government, community, and religious leaders who hold power, but also at the level of women directly targeted by FGM, mothers, and schools. In recent years, there has been an increase in people who were scheduled to undergo FGM resisting and opposing it themselves. With support from international organizations and significant investments, more people now have access to education compared to before, leading to more mothers who are knowledgeable about FGM and determined not to let their children undergo it, and more who do not want their daughters to experience the same suffering they did.

Young girls who are targets of FGM may come to believe that it is indispensable for them if their mothers and sisters have undergone it as a matter of course. Insufficient education about FGM and its health risks is one factor behind such situations. Thus, in recent years, activities such as school-level seminars on FGM to convey its dangers have been implemented. At one school in Kenya, students take part in initiatives where they sing songs to urge their parents to end FGM and allow them to live freely, and they organize events such as marches calling for the abolition of FGM that include girls who have escaped FGM, other boys and girls, and their parents.

In this way, the efforts and changes of many different people have led to a decline in FGM.

An awareness campaign for girls’ rights carried out by girls in Kenya (Photo: UN Women/Flickr [ CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Persistent challenges

Although FGM is gradually decreasing thanks to the activities of various people and organizations, many challenges remain, and the road to 0% is long. Eliminating a practice accepted as tradition is not easy and requires sensitivity to local culture and values. Therefore, providing only knowledge deemed “correct” is not necessarily effective. Likewise, trying to solve the issue through laws alone is too simplistic; even if people know it is illegal, FGM may continue in secret. Unless those who practice FGM truly feel it should not be carried out, no effort will be meaningful. However well-intentioned, blunt external intervention can backfire and hinder the reduction of FGM.

Despite the remaining challenges, the decline of FGM in Africa is indeed significant. FGM, which is said to offer no benefit to women, is not an issue that can be overlooked simply because it is a tradition. At the same time, because FGM is deeply intertwined with cultural factors, it is an issue that must be handled carefully, and delicate approaches will continue to be required.

A mother who has undergone FGM. She has decided not to let her daughter undergo FGM. (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia/Flickr [ CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Writer: Wakana Kishimoto

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

すごいですね。頑張ってください。

伝統や慣習といったものは深く根付いているもので、解決が非常に難しい問題だと考えていたので、今回のFGMの大幅な減少は非常に興味深かったです。

禁止する法律や外部の圧力などトップダウンによる方法では、当事者達の理解を得られず根本的な解決にはならないと理解した上で、伝統的指導者といった当事者達が信頼のおいている人による啓蒙活動などの草の根レベルの活動が大切なんだと改めて気づいた。草の根レベルでの活動がここまでアフリカ全土に広がり実を結んでいることは、他の国際問題に対する大きな希望であり、モデルケースになるように感じた。

これほど数字として結果が出ていることに驚きました。

ただ、依然として、同じ立場である女性でさえFGMに賛成している人もいると聞いて伝統・考え方を変えることの難しさを実感しました。

FGMの問題、存在については知っていましたが、減少している地域もあるとは驚きでした。FGMは伝統に基づいた習慣であるからこそ、その全てを否定するのではなく代替儀式を導入しているというのはすごくいい方法だなと感じました。

FGMが男性優位的な理由から存在しているって言うのを考えると、女性だけじゃなく男性にもFGMの危険性を周知する必要があるのかなと感じます。

根絶までは長い道のりになるのかもしれませんが、一刻も早くFGMにより心身共に苦しむ女性がいなくなることを、心から願っております。

根絶のために協力できることがあるのなら知りたいです。

本当に難しい問題に取り組まれる方々に敬意を表します。FGM、初めて知りました。感染症で卵管が閉塞するリスクも有る気がします。一日も速く、根絶されます様、願ってやみません。全ての人や物、自然が尊重される社会に成ります様に