Deciding for oneself whether to have children, and if so when and how many. Leading a safe sex life free from the risk of sexually transmitted infections and from violence or coercion. Becoming pregnant and giving birth safely. Astonishing data has revealed that only about half of women have decision-making power over such sexual and reproductive health and rights (sexual and reproductive health/rights).

While gender equality is prominently featured in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targeted for achievement by 2030, and women’s rights movements may seem to be progressing, why have we arrived at such a result? This article explores the current state of women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights and the background behind it.

A woman carrying a child on her back, in Nigeria (Photo: Global Financing Facility / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Current situation

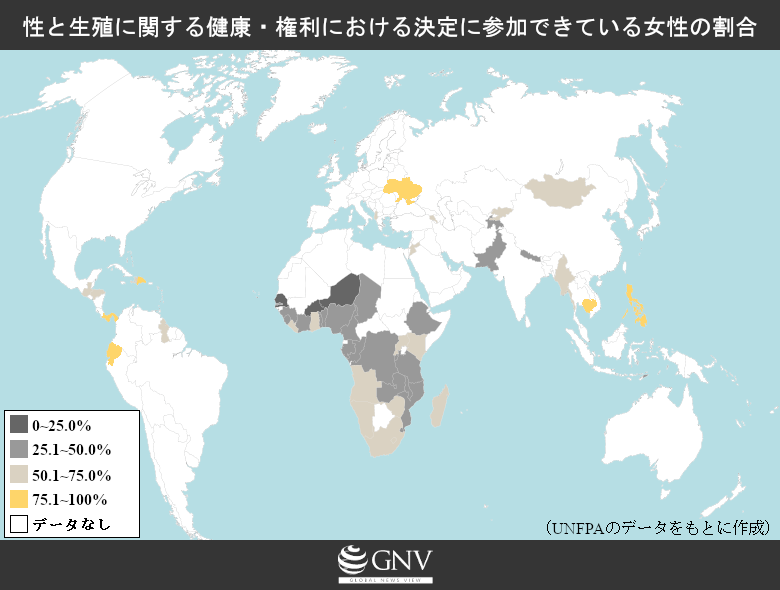

In February 2020, the UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund) published the results of a survey on women’s decision-making power in sexual and reproductive health and rights conducted in 57 countries (Note 1), mainly low-income nations. Respondents were married girls and women aged 15 to 49. The content covered three main areas of sexual and reproductive health and rights: “reproductive health care,” “use of contraception,” and “sexual relations.” In “reproductive health care,” respondents were asked whether they could participate in decisions such as whether to visit a clinic for care related to pregnancy and childbirth, sexually transmitted infections, and reproductive health. In “use of contraception,” they were asked whether the decision to use contraception was made by themselves, by their spouse/partner, or jointly. In “sexual relations,” they were asked whether they could refuse sex when they did not want it. Across these three areas combined, only 55 percent of women reported that they could participate in decision-making themselves.

Even that 55% varies greatly by region. Levels were relatively high in Southeast Asia and Central America, where 75% to 80% of women had decision-making power. By contrast, in Sub-Saharan Africa and in Central and Southern Asia, such women accounted for less than half. Breaking down Sub-Saharan Africa further, Southern Africa, including South Africa and Namibia, performed relatively well at 64%. In contrast, West Africa, including Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria, and Central Africa, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, both fell below 40%. The three West African countries of Mali, Niger, and Senegal fared worst of all, with fewer than 10% of women able to participate in decisions regarding sexual and reproductive health and rights.

How do the results look by field? Regarding health care, about 75% of women in the surveyed countries seemed able to access medical care of their own accord. However, Central and Southern Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa—especially West and Central Africa—were worse off, with more than 40% of women following decisions made by someone other than themselves, such as their husbands. For use of contraception, about 90% of women could decide for themselves. By region, all exceeded 80%, and by country, all exceeded 70%. Perhaps because methods like oral contraceptives do not require partner cooperation, this is the area in which women most exercise decision-making power among the three. As for sexual relations, about 75% of participating women appeared to have decision-making power. Regionally, all exceeded 60%, but some countries were in extremely poor condition—especially in Mali, Niger, and Senegal in West Africa, where the results suggested that roughly 70% to 80% of women may be coerced into unwanted sex with a spouse/partner.

Women visiting a community healthcare center for family planning (Photo: Global Financing Facility / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

As shown above, the degree of women’s decision-making power varies markedly by region, but some countries have also seen significant changes in recent years within their borders. For example, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the proportion of women who reported being able to refuse sex with a partner rose from 51.1% to 73.8% between the 2007 and 2014 surveys. In Rwanda and Zambia, too, the share of women able to access sexual and reproductive health care of their own accord increased by nearly 10 points within a few years. However, the changes are not all positive. Decision-making power in sexual relations fell by 15.5 points in Jordan, 13.3 points in Ghana, and 10.0 points in Ethiopia. Nigeria, which once improved by 4.0 points, later fell again by 12.8 points in subsequent surveys. Unfortunately, it cannot be said that the situation is improving across the board. The above summarizes the current overview of women’s decision-making power in sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Background

So what shapes women’s decision-making power? Even within a single country, various factors create differences. According to the UNFPA survey, the biggest influence is the level of education. In the combined global data across the three areas, when comparing women with no education to those with primary education, the latter had a 38-point higher rate of decision-making power. For example, in Tajikistan, fewer than 10% of women with no education could decide on their own sexual and reproductive health care, whereas the figure exceeded 70% among women with higher education. Receiving education can bring major changes in life, such as access to information and improved socioeconomic status. This makes it easier to assert oneself in household communication and increases one’s voice. Even focusing only on sex education, gaining accurate knowledge and information about sexuality and reproduction forms the foundation for self-determination, and is therefore crucial.

A girl studying in a classroom, in Guatemala (Photo: World Bank Photo Collection / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Decision-making power also increases with age. The most notable change occurs between ages 20 and 34, with little noticeable change after age 35. For example, in Pakistan, only about 25% of girls aged 15 to 19 can be involved in decisions about their own health care, but among women aged 45 to 49, the proportion exceeds 70%. Household wealth is another factor: in Mozambique, the proportion of women able to refuse sex with a partner is about 45% in the poorest household group, compared to nearly 80% in the wealthiest group. Additional factors that enhance women’s decision-making power in sexual and reproductive health and rights include higher age at first marriage and access to media such as newspapers, television, and radio. However, whether one lives in an urban or rural area did not create notable differences.

Why, then, are there such large differences between countries? First, as with within-country comparisons, education and poverty likely have a major impact. In countries where opportunities for education are limited and poverty is widespread, women’s decision-making power is harder to exercise. Differences in legal frameworks are another factor. The UNFPA survey also examined, across 107 countries home to 75% of the world’s population, the extent to which each country has developed legal frameworks to ensure equal sexual and reproductive health and rights. These legal frameworks were divided into four areas: “maternal health services,” “contraception and family planning,” “sexuality education and information,” and “sexual health” such as sexually transmitted infections. In the Philippines, where more than 80% of women reported having decision-making power in sexual and reproductive health and rights, legal readiness for sexuality education and information was 100%, and 95% for sexual health. By contrast, in Senegal, where only 7% of women had decision-making power, achievement was 22% in the area of contraception and family planning and 0% in sexuality education and information. In countries advancing legal frameworks, younger generations can obtain accurate information through education and can easily access STI testing, making it easier to secure sexual and reproductive health and rights equally. However, in 28% of countries where abortion is legal, spousal/partner consent is required, and in some countries the legal framework presumes spousal/partner involvement. Therefore, the mere existence of laws does not automatically guarantee women’s decision-making power.

A woman receiving counseling from a doctor, in Cambodia (Photo: ILO Asia-Pacific / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Social customs are also related. In regions where male-dominated culture is deeply rooted, it is difficult for women to voice opinions to their husbands in the first place, and open discussion of sexuality and reproduction is often taboo, hindering women’s autonomy. In such regions there are families who do not allow girls to receive an education. In places where having a large family is a status symbol, husbands may oppose contraception without regard for the woman’s wishes or health. Child marriage—marrying girls at ages when they should be receiving education and are physically too young to be fit for pregnancy—is sometimes accepted and even becomes a symbol of status for men. Religion is another factor that cannot be ignored. For example, in some branches of Islam and Christianity, contraception and abortion are prohibited by doctrine. Due to factors like these, women’s situations regarding decision-making power vary greatly within and between countries.

Impact

What impact does the current lack of women’s decision-making power over sexual and reproductive health and rights have? First and foremost, it affects the health of women themselves and their children. Approximately 300,000 pregnant and postpartum women die each year worldwide, and 2.6 million babies are stillborn. Many of these cases are due to causes that are fully preventable with modern medical technology—such as failing to notice abnormalities because checkups were not received, resulting in delayed treatment. While geographical and financial barriers can impede access to appropriate medical care, a lack of decision-making power can prevent women from receiving maternal health checkups or delay access to health care even when they feel unwell, costing many lives that could have been saved and babies that could have been born. Even when lives are saved, disabilities can remain. For example, prolonged labor can damage the birth canal, causing severe pain and urinary incontinence—an avoidable condition known as obstetric fistula—leading to discrimination and loss of livelihood. Inadequate obstetric care affects not only women’s bodies but also their self-esteem and socioeconomic status.

Beyond pregnancy and childbirth, the female genital cutting (FGM) of girls, which persists as a tradition in some countries, also reflects a lack of decision-making power. Practiced with the aim of controlling female sexuality, this custom functions as a rite of passage and is virtually impossible for the women themselves to refuse. It poses significant burdens for girls and women, including complications during pregnancy and childbirth, risk of infection, and, in the worst cases, death. In this way, the lack of autonomy over health care has serious impacts at various stages of women’s lives.

The lack of women’s decision-making power also affects education. Girls forced into child marriage are at ages where autonomy is hard to exercise and are likely to be disadvantaged in using contraception or refusing sex. Against such a background, girls who become pregnant early and unintentionally often cannot continue attending school due to factors such as discrimination and financial constraints. Once deprived of educational opportunities, these girls face disadvantages in the labor market and find it difficult to improve their socioeconomic status. The lack of women’s decision-making power in sexual and reproductive health and rights thus becomes a factor that hinders the expansion of women’s rights in other areas such as education and wages.

A female student in Colombia (Photo: World Bank Photo Collection / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Measures

In recent years, various measures have been implemented to change this serious situation. The background includes a shift in awareness regarding sexuality and reproduction. Beginning around the 1980s, governments concerned about population growth introduced systems for family planning and maternal and child health, and the spread of HIV infection increased condom use, improving public awareness and outcomes. For example, Uganda was able to significantly reduce HIV infection between the 1980s and 1990s. This is said to be largely due to policies that encouraged open discussion of sexuality and reproduction—previously taboo—even for women.

Building on this momentum, many measures have continued to be implemented in recent years. A few examples: Globally, in 2000, the UN Girls’ Education Initiative (UNGEI) was launched to eliminate gender disparities in education, supporting national education policies to achieve gender equality. In 2016, UNFPA and UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) launched an initiative to end child marriage. Targeting 12 countries where child marriage is particularly severe, the initiative urges increased national budgets to eliminate the practice and supports girls’ school fees, given that access to education reduces the likelihood of child marriage.

At regional and national levels, there have been efforts in Africa to combat FGM. Governments have banned FGM by law, and traditional and religious leaders have directly appealed to communities to end the practice. Increasingly, girls and women who would be subjected to FGM—and their parents—are standing up to refuse it, leading to a significant reduction in cases.

A community health worker advising a pregnant woman on antenatal care, in India (Photo: Save the Children / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

As a maternal and child health example, consider Nepal. In Nepal, a geographic feature where one-third of the country is mountainous and the low status of women made access to medical facilities difficult. To address this, health centers were established across the country, and abortion was legalized so that safe procedures could be accessed, reducing maternal mortality. In Ecuador, too, activism by women has led to the submission of a bill to relax the requirements for abortion, which is generally prohibited—showing signs of change. As noted in the UNFPA survey above, in the field of sexual and reproductive health and rights, there is a certain correlation between legal frameworks and women’s decision-making power. Therefore, as in the examples from various African countries, Nepal, and Ecuador, legal reforms are likely to improve the situation. In this way, some countries and organizations are taking proactive action.

However, the problem cannot be solved by international organizations and government policies alone. Ultimately, whether a woman has decision-making power is determined within each household. This does not mean women must decide alone. There is evidence that joint decision-making with a spouse/partner leads to higher access to health care, and, as the example of Uganda shows, the ability to discuss sexuality and reproduction with a spouse/partner is crucial.

A woman holding her baby in a hospital (Photo: Children’s Investment Fund Foundation / Flickr[CC BY-NC 2.0])

There are many women around the world who do not have decision-making power over their own sexual and reproductive health and rights. Even within countries, circumstances vary widely depending on factors such as education, age, and income, leaving major challenges to be addressed. Moreover, when the level of women’s rights in sexual and reproductive domains is low, inequalities in other areas, such as education and wages, also become entrenched. Although the background to the problem is complex, it is necessary to follow the approaches of countries and regions that are showing improvement and to implement appropriate measures.

Note 1: Of the 57 countries surveyed, 36 were from Sub-Saharan Africa, 7 from South America and the Caribbean, 5 from Central and Southern Asia, 5 from East and Southeast Asia, 2 from North America and Europe, and 2 from West Asia and North Africa.

Writer: Suzu Asai

Graphics: Yumi Ariyoshi

現状から対策まで流れが分かりやすく、理解が深まったすてきな記事でした!まだまだ自分で決定権を持てていない女性が世に多くいることが身にしみて感じられました。これから対策を講じる国や地域が増えていくことを願います。

リプロダクティブヘルスについて自分自身で決定権を持つことができる女性が全体の約半数しかいないというのはとても衝撃的でした。国際組織での運動や国の政策があっても、最終的な女性の決定権はそれぞれの家庭で決まるという言葉が印象的で、確かにそうだなと思いました。そういった中でも、教育と法整備を両立させて、課題解決へと向かっていくといいなと思いました。

日本のように、性に関する話をすること自体が憚れる社会の風潮がある場合、制度だけでなく、長期的な教育が必要になると思います。