In Myanmar, armed conflict continues between the military, which seized power in a 2021 coup, and multiple anti-government forces. In February 2024, a national conscription law covering men and women of certain ages came into force, and from April some eligible people began to be drafted. In the month the enforcement of conscription was announced, citizens attempting to flee abroad to avoid the draft rushed passport-issuing offices, and a stampede in the crowd led to the deaths of two women in an accident. Among young people who received draft notices, some have reportedly chosen to join anti-government forces.

This article looks at how conscription works around the world and its issues from various perspectives.

Conscripts in Singapore (Photo: Daylon Soh / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Overview of conscription

Armed forces exist in most countries around the world, with exceptions such as Costa Rica and Panama. However, the ways they secure personnel vary by country and fall broadly into volunteer enlistment and compulsory enlistment. Volunteer enlistment is a system in which applicants join of their own accord as a profession, while compulsory enlistment is a system in which people of certain ages are forced to serve for a certain period. Compulsory service can be further divided into three types, one of which is conscription. Conscription is a system under which people of certain ages are registered as eligible for service and may not be called up in peacetime. The second is selective compulsory service: unlike random conscription, selective compulsory service calls up medical personnel, mechanics, pilots, and others to fill needs in those specific fields. The third is statutory compulsory service: compulsory service exists in law but people are rarely actually called up. There are cases where there are enough voluntary applicants that there is no need to call up compulsory participants. In practice, many countries operate a combination of these systems.

The history of organized obligations of citizens to perform military service goes back to ancient Egypt. However, there are differences between ancient forms of conscription and modern conscription: many ancient systems were not universal conscription but selective. Modern conscription began in France after the French Revolution; Prussia then adopted universal conscription, and that system was widely adopted, especially across Europe.

Conscription today

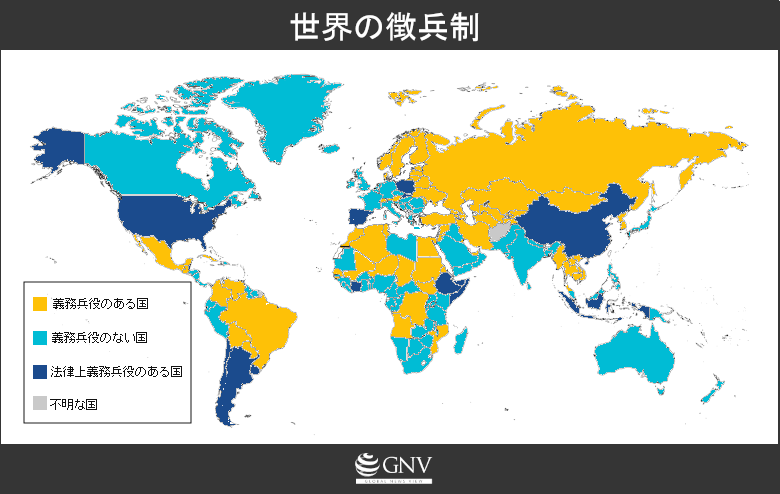

As of September 2024, 68 countries have compulsory military service, 17 countries have compulsory service in law, and 93 countries have no military service (※1). There are also countries and territories where it is legally recognized but the level of implementation is unclear, and countries with no military at all. We compare these various systems in terms of obligation, age, gender, and the mechanisms for exemptions from the draft.

As noted above, military service is compulsory in some countries and voluntary in others. Some compulsory systems use a lottery, such as Thailand. In Thailand, men aged 21 are required to undergo a draft examination every 4月, and those who pass take part in a lottery. Those who draw a red card are required to serve for up to two years, while those who draw a black card are exempt.

Latvia, meanwhile, reinstated conscription in 2023 due to reasons such as a shortage of soldiers, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that began in 2022. Many aspects of the system remain undecided, but for the January 2024 draft, a lottery was used. The draw was conducted randomly using a computer program and was broadcast live.

The ages at which people are subject to military service also vary by country. Many set the lower age limit at 18, but in Eritrea those aged 16 and above are subject to the draft, and students are forced to serve. Upper age limits vary: in Ukraine, in response to Russia’s invasion that began in 2022, men aged 18 to 60 are required to register with the military and are barred from leaving the country. In Russia, men aged 18 to 27 were previously subject to one year of compulsory service, but from 2024 the upper limit was raised to 30. The Russian government prohibits those who have received draft notices from going abroad.

In recent years, some countries also conscript women. Countries that draft both men and women include the Nordic states of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, as well as Eritrea, Israel, Mozambique, North Korea, and Myanmar. North Korea was the first in the world to conscript women, but men and women are not subject to the same term lengths: men are required to serve 11 years, while women must serve 6 to 7 years, by law. Only Norway and Sweden impose equal service conditions on men and women. Some countries where only men are currently obligated are considering introducing mandatory service for women. For example, in South Korea, there is growing public opinion in favor of women’s conscription due to population decline and dissatisfaction among men.

Draft exemption mechanisms also differ by country. Exemptions allow those who meet certain criteria to avoid conscription, with criteria ranging from health to higher education. In Israel, for example, both men and women have an obligation to serve, but women are exempt due to faith, pregnancy, or marriage. Haredi Jews (※2) had also been exempt, but amid the prolongation of military operations in Gaza since 2023 and the potential escalation of conflict with Lebanon’s Hezbollah, the Supreme Court issued a ruling in June 2024 abolishing the exemption.

In Egypt, Egyptians living abroad can avoid conscription by paying $7,000. In Egypt, men aged 18 to 30 are subject to compulsory service, and become reservists for 9 years after service. Men of draft age cannot obtain a passport—and thus cannot leave the country—unless they have completed service or been exempted, so those of conscription age living abroad have sometimes avoided returning home for fear of exit restrictions. This system was introduced in 2023 at the request of Egyptians overseas and to bolster the government’s foreign currency reserves.

New recruits in Israel (Photo: charcoal soul / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

Furthermore, some countries impose an obligation to serve but allow citizens to choose non-military national service instead of military service. In Switzerland, for example, citizens can choose among three options: repeated short-term military service periods; participating once in a longer-term military service; or engaging for a longer period than military service in civilian work in fields such as health care, welfare, or environmental protection.

Can conscription be justified?

We have reviewed the diverse military service systems adopted in different countries. But can a system that forces citizens into military service be justified? Some argue that conscription was invented for military convenience and is difficult to justify from other perspectives. Here, we consider its legitimacy from two perspectives: human rights and the social contract.

On human rights, there are claims that conscription is a human rights violation and constitutes a crime against humanity, as argued by some. The right to life is one of the most fundamental human rights, and the right to refuse to take another life can also be considered a basic human right. Therefore, a system that obligates citizens to kill under compulsion—conscription—can be said to violate those rights. Moreover, conscription may fit characteristics of crimes against humanity as defined by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. For example, conscription may involve the “forcible transfer” of conscripts or the “severe deprivation of physical liberty,” both of which are categorized as crimes against humanity. Drafting only men could also constitute “persecution against an identifiable group,” namely the gender group of men.

The social contract is also often a central argument in this debate. The social contract theory, proposed by the 17th-century European philosopher and political philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, holds that society is constituted by a social contract—an agreement between the people and the state—and that individual wills must submit to the general will produced by that agreement. In this context, military service is argued to be part of the duties people owe as members of society. However, the state exists to protect the lives of its citizens, and the social contract is understood to be concluded on that premise; conscription is a system that endangers citizens’ lives. Moreover, if a state is to demand conscription as a duty, it can be argued that, to guarantee its legitimacy, it must wage just wars under an uncorrupt political system. Yet the evaluation of any war is subjective, and some argue that no war is truly just.

A poster urging opposition to a referendum on conscription in Australia (1916) (Photo: Chifley Research Centre / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Societal impacts of conscription

Conscription has a variety of impacts on society. Here we look at effects from military and economic perspectives.

As noted, the legitimacy of conscription is contested, but how effective is it militarily? Pro-arguments include that conscription is an effective defense measure and that it fosters patriotism among citizens.

The most obvious security benefit of conscription is that it is easier to maintain troop numbers than under a volunteer-only system, a point often raised. On the other hand, aside from maintaining numbers, its military effectiveness in modern warfare may not be particularly high, according to some assessments. Reasons include the training and experience demanded of soldiers and factors such as morale. In the United States, for example, it has been noted that the military has been higher quality since moving to an all-volunteer force compared with the era of the draft. Thanks to higher morale and greater experience, U.S. troops in the volunteer era are said to be superior not only in basic soldiering, but also in skills such as computing and engineering.

Furthermore, modern warfare is increasingly high-tech, using missiles, drones, and cyberattacks. It takes a long time to train soldiers able to handle such systems, but modern conscription often sets service terms of a few months to around 2 years, making it difficult to cultivate the necessary personnel. In Taiwan, for example, there is a volunteer force of full-time soldiers, but men aged 18 to 36 must also complete compulsory service. Some participants have questioned the value of such service due to the lack of practical training and curricula not aligned with new weaponry. To address these issues, the government extended the service term from 2024 and introduced new training using weapons such as anti-tank missiles.

As for the claim that conscription fosters patriotism or a sense of civic duty toward the state, some research suggests the opposite is possible. A study of several European countries indicates that military service may create a sense of belonging to the military while lowering trust in institutions such as the legal system, parliament, and politicians. Generations exempted from conscription had higher levels of trust in such national institutions than generations that were conscripted. Thus, conscription does not necessarily cultivate a sense of belonging or patriotism toward the state.

Finnish conscripts (Photo: NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Next, the economic impact of conscription. It has been pointed out that forcing young people into military service can depress long-term earnings and interrupt education. In countries with compulsory service, as noted, the lower age limit is often 18, and serving during youth—when investments in human capital would otherwise be made—can affect income and education. In the Netherlands, for example, research has found that conscription participation reduces lifetime earnings and degree attainment rates. The same study estimates that conscription reduces the average wage across society by 1.5%. On the other hand, military experience can build skills such as leadership, discipline, and teamwork, and some argue that this experience can be helpful when job hunting.

Problems arising in the implementation of conscription

We have seen that the existence of conscription does not necessarily confer military, economic, or social advantages, and many problems arise in its implementation.

First, at the drafting stage, there can be unequal conscription. Drafts are not always conducted randomly among those eligible. During the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 70s, for example, two-thirds of U.S. troops were volunteers and one-third were draftees, but those drafted in the early years were disproportionately from the poor and minorities. One reason was the deferment system: deferments were granted for reasons such as university enrollment or health, which favored those who were better off economically and white men more likely to have connections with examiners. After criticism, the draft law was revised in 1969 to increase randomness.

Forced conscription is another major problem. In Myanmar, for example, a conscription law took effect in February 2024, spreading fear among those eligible. Some people fear being forced into the military not through formal procedures, but through police arrests or abductions. Similar problems are occurring in Ukraine. Following Russia’s invasion that began in 2022, recruiting officers constantly look on public transport and in city streets for eligible men evading the draft. Those identified are taken to enlistment centers, leading many eligible men to fear such situations and avoid going out.

An Eritrean man in an Ethiopian refugee camp who went into exile two years after being conscripted (Photo: ODI Global / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Violence is one problem that can occur during service. In Thailand, for example, there have been confirmed cases of abuse by superiors against new recruits within the military and sexual abuse of homosexual recruits. In Eritrea, where conscription covers both men and women aged 16 and up, corporal punishment and forced labor during service are reportedly tolerated.

Another issue that can arise during and after service is adverse health effects. In South Korea, where men aged 18 to 28 serve for about two years, military life—despite its image of regular routines and exercise—has been linked to health harms due to alcohol and tobacco use. The normalization of drinking and smoking in the military and the stress of exposure to dangerous situations can increase consumption during service, with effects persisting after discharge. In Thailand, in addition to alcohol and tobacco, the prevalence of drugs in the military is also a problem.

Military service can also affect crime rates. One possible reason is that conscription during youth lowers psychological barriers to the use of weapons and violence. In Argentina, for example, men aged 21 and older were assigned service by lottery until 1995, and research shows that those who actually served as conscripts had higher crime rates.

People who refuse the call-up

Some people refuse to serve even when called up. Refusals based on conscience, religion, political beliefs, or similar grounds are called conscientious objection. Responses to conscientious objectors vary; historically, despite some religious exceptions, they were often treated as lawbreakers. In the modern era, a variety of responses have developed. In Norway and Sweden, for example, service is mandatory, but conscientious objectors are allowed to perform civilian service as noncombatants or as civilians. Some countries do not recognize the right to conscientious objection. In Thailand, for instance, the concept had not taken root because those with means could avoid the draft by other means such as bribes. In April 2024, however, the first conscientious objector emerged, refusing service as a violation of human rights. He was not arrested, but may face up to 3 years in prison for the crime of civil disobedience.

What do international bodies say about conscientious objection? The Human Rights Committee and the United Nations Human Rights Council recognize conscientious objection as a legitimate exercise of the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and related instruments, as set out in their standards. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (ONHCR) also provides recommendations, under its mandate to promote and protect the enjoyment of rights by all people, including criteria for procedures to apply for conscientious objection.

A demonstration burning draft cards in the United States (Photo: Washington Area Spark / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

There are various ways to refuse conscription. In the United States during the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 70s, for example, thousands refused to serve in Vietnam on anti-war grounds, but when applying as conscientious objectors, they were required to perform non-military service for the government, so many refused by other means as well. Methods included using deferments, such as staying in university or becoming a minister, options permitted by the system, as well as fraudulent methods like feigning illness or forging draft cards. There were also more radical forms of resistance, such as demonstrations by students burning draft cards and armed resistance movements to refuse service. To prevent draft resistance, authorities deployed troops to suppress protests and searched and arrested draft resisters without warrants.

In Myanmar, as noted, a conscription law has been in effect since February 2024, and many people are trying to evade the draft. Although draft evasion carries penalties of three to five years’ imprisonment and fines, many hope to flee abroad due to fears of being sent to the front lines without proper training and having to fight their own people.

In Eritrea, by contrast, as noted earlier, corporal punishment and forced labor are tolerated during service and in some cases service can be indefinite, among other problems. Refusing service is not permitted; draft evaders are taken by authorities and sent to the military. Authorities also punish evaders’ families through detention or confiscation of livestock. To escape such conditions, many people become refugees and seek to leave the country.

Global trends

From the 1970s to 2010, conscription showed a declining trend worldwide. In recent years, some countries have abolished it: in Jordan, for example, conscription was abolished in 1991, and since 2020 unemployed people of certain ages have been required to participate in programs that include construction, tourism, and military training. In Ecuador, conscription was suspended in 2008, making service voluntary for both men and women. In Thailand, public opposition to conscription is growing. As protests drew public attention to the issue, abolition of conscription became an election issue, and the military was forced to consider transitioning to a volunteer system. No change in the draft has yet been observed, but future developments warrant attention.

Meanwhile, some countries are considering bringing back conscription. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that began in 2022, there have been moves to reinstate conscription in several European countries. Morocco, which once abolished conscription, reintroduced it in 2019. And, as noted, in Myanmar, a conscription law was implemented in 2024.

It remains to be seen which systems countries around the world will adopt in the future.

Note 1: The classification of countries’ military service systems in this article is based on World Population Review , with some modifications.

Note 2: Ultra-Orthodox Judaism is one sect of Judaism, comprising about 13% of Israel’s population. Ultra-Orthodox political parties have long supported Benjamin Netanyahu’s government in exchange for draft exemptions and funding.

Writer: MIKI Yuna

Graphic: MIKI Yuna

徴兵制の現況や種類、社会や人々へ与える影響まですっきりとまとまっていて良かったです。徴兵制が侵害する人権について、どういった種類があるか深く考えたことがなかったので勉強になりました。

入隊の方式が徴兵制以外にもたくさんあることに対して、まずは驚きました。加えて、義務兵役を課している国が想像以上よりも多い一方、兵役に関する批判や、人権侵害だという主張は私自身が思ったよりもなされていないんだなという印象を持ちました。

世界に置いて戦争の勢いが増す中、徴兵制は全ての国民にとって意識すべき問題だと感じた。国から強制的に徴兵制度に参加させられることについて、戦争が間近に迫る国にとってはまさに命を脅かす行為であり、大いなる人権の侵害であると思う。各国の徴兵制の比較と共に、徴兵制の正当性についてもデータをもとに知れたのは良かった。

徴兵制の種類が一つではないことに驚きました。以前、韓国の某男性アイドルグループのメンバーが徴兵されたというニュースを見た際、韓国は大変だなあと思っていましたが、意外にも徴兵制を採用している国が多くあり、驚きました。

小学校の文章の参考にしたいところが簡単にたくさんまとまっていていいなと思った