In May 2021, GNV covered the politics of the Pacific Island countries in an article titled “A crisis for Pacific nations?.” Using as an entry point the event in February 2021 when five states (Palau, the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, and Nauru) declared they would withdraw from the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), that article outlined Pacific regional politics with a focus on the PIF.

As of June 2024, more than three years later, the above five countries are in a state of membership in the PIF. However, the path to that point was full of twists and turns. This article follows the developments surrounding the withdrawal declarations by those five Micronesian countries and examines the politics around the Pacific Islands.

Opening ceremony of the 2023 PIF Leaders’ Meeting (Photo: US Embassy / Flickr [Public Domain])

目次

About the Pacific Islands

The Pacific Islands are conveniently divided into Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia. Although this is an artificial classification created by French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville, it has become widely accepted and is still used. For example, Melanesia includes Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands; Polynesia includes Tuvalu and Samoa; and Micronesia includes Palau and the Marshall Islands.

For a detailed history of the Pacific Islands, please refer to past GNV articles, but we will offer a brief summary here. First, the development of the Pacific Islands was driven mainly by people who migrated during two periods, roughly 40,000–60,000 years ago and about 5,000 years ago. These Indigenous peoples developed navigation technology and expanded the development of various islands and trade.

In the 16th century, colonial rule by European and American countries began. The suzerain powers were mainly Britain, France, Germany, Spain, and (after the Spanish-American War) the United States. To secure resources, they established plantations on the Pacific Islands, and the local people faced harsh conditions. After World War I, Germany’s defeated colonies became League of Nations mandates, but in practice this merely changed the suzerain countries to Australia and Japan.

After World War II, when parts of the Pacific Islands were occupied by Japan and became battlefields, the region gradually moved toward independence. Beginning with the independence of Western Samoa (now Samoa) in 1962, countries such as Nauru, Tonga, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea followed in quick succession. At the same time, as of 2024, some territories have still not achieved independence. For example, France continues to regard French Polynesia and New Caledonia as part of its territory, and in New Caledonia in particular the independence movement has intensified. Before independence and in non-self-governing territories, the Pacific Islands were also used as sites for nuclear tests by Western countries, and the suffering of those affected continues to this day.

Finally, regarding the economies of the Pacific Islands, many countries rely on tourism, fisheries, remittances from overseas workers, and assistance from other countries due to small land areas and populations and limited resources. According to a World Bank study, overall economic growth in the Pacific slowed in 2023, and recovery is lagging in countries severely affected by cyclones and drought. The Pacific Islands are geographically highly vulnerable to climate change and natural disasters, and this is seen as a challenge for their future economies.

What is the Pacific Islands Forum?

The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) is a mechanism in which countries and territories of the Pacific region gather and which functions as a venue for dialogue and regional cooperation across a wide range of fields including politics, economics, and security. As of June 2024, 16 countries and 2 territories are members; 2 territories are associate members; and 4 territories participate as observers (※1).

It originally began as the South Pacific Forum (SPF), a venue for dialogue on common issues among South Pacific countries, but gradually expanded in scope, began dialogue with extra-regional countries in 1989, and was renamed the PIF in 2000. It has also formed a partnership with the United Nations to discuss issues such as climate change.

As a PIF activity, a Leaders’ Meeting is held every year. In addition to member states, associate members, international organizations, and extra-regional dialogue partners also participate. Decisions at this meeting are made by consensus. The chair rotates annually; the 2023 Leaders’ Meeting was held in the Cook Islands.

The PIF Secretariat in Suva, the capital of Fiji, implements the policies discussed at the Leaders’ Meeting. The head of the Secretariat is the Secretary-General, and a notable feature is that an individual, not a state representative, is selected. Although the Secretary-General is also selected by consensus, during the 2021 selection there was fierce confrontation, the method was changed to a secret ballot, and it ended with the shocking result of a withdrawal declaration from five Micronesian countries.

Micronesia’s 2021 withdrawal declaration

From here, we take a closer look at what happened after the withdrawal declaration by Micronesian states over the selection of the PIF Secretary-General in 2021.

First, a brief look at the process leading up to the Micronesian states’ withdrawal declaration (for details, please see the past GNV article). There was originally an agreement commonly called a “gentlemen’s agreement” regarding the selection of the PIF Secretary-General, under which candidates recommended by each subregion—Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia—would be chosen in turn. 2021 was Micronesia’s turn. Micronesia, which has long argued it is overlooked in the Pacific region due to its relatively small population and economy, stated it would not hesitate to leave the PIF if this unwritten rule were not honored. In the end, the unwritten rule was broken during the 2021 selection, and the Micronesian candidate lost. As a result, five countries in Micronesia (Palau, the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, and Nauru) declared they would withdraw from the PIF.

If the five Micronesian countries were to withdraw, the Forum would lose nearly one-third of its members at once. Their withdrawal would mean that islands north of the equator would not participate in the PIF. The PIF would no longer be a forum for the entire Pacific, and would revert to the South Pacific-focused SPF era. If the withdrawal were realized, Pacific regionalism would significantly retreat. On this point, it has been suggested that Australia and New Zealand, the major powers within the PIF, did not defend this unwritten rule and instead moved in a direction that broke it. In particular, Australia clearly did little to help the Micronesian candidate be selected and was criticized for failing to anticipate how the Micronesian states would react.

The PIF Secretariat in Suva, the capital of Fiji (Photo: Stemoc / Wikimedia Commons [CC0 1.0 UNIVERSAL DEED])

Developments in the Pacific Islands after the withdrawal declaration

About a year after the withdrawal declaration, in February 2022, the Micronesian states temporarily reversed their withdrawal from the PIF (※2). They took this step because Henry Puna (former Cook Islands prime minister), who had taken the Secretary-General’s post in 2021 after defeating the Micronesian candidate, pledged to resign earlier than the original term (two terms, six years). Behind the scenes, unlike during the 2021 selection, Australia was said to have actively engaged Micronesian countries politically.

In addition to Puna’s early resignation, it was also agreed that the next PIF Secretary-General would be appointed from Micronesia. To prevent another rift over the Secretary-General selection, the “gentlemen’s agreement” to rotate the post among Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia would be formally codified. Furthermore, measures to strengthen Micronesia’s standing—such as establishing new PIF offices in Micronesian countries—were announced one after another. Micronesia had long argued it was being overlooked in the region, and this series of agreements (the Suva Agreement) was expected to improve that situation.

However, on the eve of the PIF Leaders’ Meeting scheduled to begin on 11 July 2022, at which the Suva Agreement was to be endorsed, Kiribati’s President Taneti Maamau abruptly announced that he would not attend and that Kiribati would withdraw from the PIF. In a letter to PIF Secretary-General Puna, President Maamau cited dissatisfaction over the 2021 Secretary-General selection and concerns about the Suva Agreement as reasons for the withdrawal.

President Taneti Maamau of Kiribati (Photo: UNIS Vienna / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Kiribati diplomatically recognized China in 2019 and has built close ties, and the opposition in Kiribati criticized the PIF withdrawal as being influenced by China. China has denied such speculation, and there are opinions that this view is too simplistic. Regardless of whether China was influential or not, Kiribati’s withdrawal was a major blow to the PIF, and the 2022 Leaders’ Meeting, which had been expected to promote regional unity through approval of the Suva Agreement, became a turbulent meeting once again.

Consultations continued after Kiribati’s withdrawal, and six months after the Leaders’ Meeting, in February 2023, Kiribati announced it would rejoin the PIF. Kiribati’s return is thought to have been largely due to a summit the previous month between Fiji’s Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka and President Maamau.

The 2023 Pacific Islands Forum Leaders’ Meeting

With Kiribati back in the PIF, the 52nd Pacific Islands Forum Leaders’ Meeting was held in the Cook Islands from November 6 to 10, 2023. Prime Minister Mark Brown of the Cook Islands, the chair, set the theme as “Our Voices, Our Choices, Our Pacific Way: Promote, Partner, Prosper.” This signaled the importance of Pacific Island countries themselves leading decision-making on regional matters while cooperating with partner countries. However, the leaders of the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and New Zealand were absent, and clouds were already gathering over the region-led approach.

From here, we highlight several items discussed at the 2023 PIF Leaders’ Meeting: the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent, climate change, deep-sea mineral extraction, and the selection of the PIF Secretary-General.

At this meeting, the first-phase implementation plan for the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent (the 2050 Strategy) was approved. The 2050 Strategy presents a vision for Pacific Island countries to cooperate to advance peace and sustainable development in the region. Specifically, it lists ten objectives across seven themes, including “political leadership and regionalism.” Among them, the sense of crisis over climate change is particularly emphasized. Although greenhouse gas emissions from the Pacific Islands account for only 0.03% of the global total, they are considered among the most affected by climate change. While the 2050 Strategy itself was approved at the previous year’s Leaders’ Meeting, within just about a year it reached adoption of an implementation plan. This reflects the region’s urgency on climate change.

Kiribati affected by climate change (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Next, we look at specific climate measures discussed at this meeting: the Pacific regional framework on climate mobility and the Pacific Resilience Facility (PRF). The regional framework is a comprehensive approach for Pacific Island countries to address the impacts of climate change. A distinctive feature is that it lists as a priority the right of people in the Pacific, who are in a vulnerable position vis-à-vis climate change, to continue living in their homes without becoming climate refugees.

The Pacific Resilience Facility is a mechanism to mobilize funding to help Pacific communities exposed to climate and disaster risks build resilience and recover from disasters. Damage from cyclones and other disasters is immense in the region, and reconstruction costs are a heavy burden. The idea is to reduce these costs even before disasters strike by raising funds from outside. It is scheduled to launch in earnest in 2025, and a large funding pledge has reportedly already been made by Saudi Arabia.

As another environment-related issue, deep-sea mineral extraction was also discussed. Deep-sea mineral resources generally refer to manganese nodules formed when iron and manganese dissolved in seawater precipitate as oxides. Over millions of years, these nodules have accumulated cobalt, nickel, and rare metals, and are therefore expected to be a new source of supply. Such mineral resources have been found through exploration in the Pacific, and there is ongoing division within the PIF over whether to proceed with extraction. For example, the Cook Islands promotes extraction. At this Leaders’ Meeting, the Cook Islands’ prime minister himself brought deep-sea nodules and presented them as souvenirs to other leaders. Meanwhile, because the impact of deep-sea mining on the ocean and ecosystems remains unclear, countries such as Fiji and Papua New Guinea oppose it.

Regarding the selection of the Secretary-General, which had caused a crisis of division since 2021, the meeting settled on appointing Baron Waqa, former president of Nauru. Micronesian leaders met in February 2023 and agreed to nominate a new Secretary-General from Nauru. While this appointment was welcomed by Micronesian countries, human rights groups and former Nauruan MPs criticized Waqa for his conduct during his presidency. Questions were raised about the selection even within this PIF meeting, leading to a scene in which Nauru’s president walked out in displeasure. The Secretary-General’s future actions will need close watching.

Baron Waqa (Photo: World Humanitarian Summit / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

Beyond what we covered here, leaders also discussed, decided, and announced various matters including fisheries policies, a new agreement between Australia and Tuvalu (the Falepili Union Treaty), and a declaration on gender equality.

So did the 52nd Pacific Islands Forum Leaders’ Meeting unite the region as the PIF aspires to do? Unfortunately, tensions are seen as remaining high among Pacific countries. The aforementioned behavior of the Nauru president is one example, and the PIF still faces multiple issues. As activities by extra-regional partner countries become more active, the PIF will face difficult steering.

Global powers moving closer to the Pacific Islands

We now look at several major powers approaching the Pacific Islands. But first, why are they doing so? One reason is the region’s geographical attributes. The Pacific Islands lie along vast Pacific sea lanes and are considered useful as refueling bases. In addition, deep-sea mineral resources and fisheries like those mentioned earlier are widely distributed across the Pacific, and major powers value these resources.

As of June 2024, there are as many as 21 extra-regional dialogue partners of the PIF. In this chapter we cover China, which has been strengthening political ties rather than economic assistance, and the United States, which itself has territories in the Pacific and exerts strong influence. In the next chapter, we cover Indonesia, geographically close but with historical frictions with the Pacific Islands, and Australia, the major power within the PIF.

First, China. Compared to the United States and Australia, China is a relatively recent actor in the Pacific Islands. Even so, it has been a PIF dialogue partner for over 30 years, so its history there is not short.

According to the Lowy Institute’s Pacific Aid Map, China gradually expanded its economic assistance to the Pacific Islands in the 2010s. However, it never overtook Australia’s total and has in fact decreased its economic assistance since the late 2010s. One reason is that much of China’s assistance takes the form of loans, leading to large debts in recipient countries and making Chinese aid appear less attractive to some.

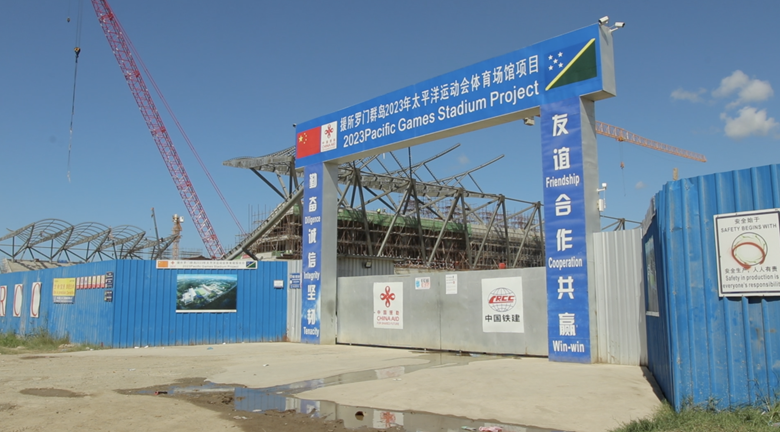

China itself has also shifted policy toward deepening direct political ties with the Pacific Islands rather than indirectly exerting influence through economic assistance. Using financial aid to pry Pacific nations away from Taiwan and establish diplomatic relations with China is a long-standing tactic in the region. In recent years, the Solomon Islands and Kiribati in 2019, and Nauru in 2024, severed ties with Taiwan and established relations with China.

A China-supported construction project in the Solomon Islands (Photo: 美国之音记者莉雅、久岛 / Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Among these countries, the Solomon Islands has especially close ties with China. In March 2022, a security agreement between China and the Solomon Islands was leaked. Under the agreement, China can deploy armed police at the Solomon Islands’ request. In 2023, as part of an upgrade of relations to a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” the two countries signed a new agreement, further deepening ties.

The United States, which has long held strong influence in the Pacific, has pushed deeper engagement to counter China’s activism. The U.S. has multiple territories in the region (Hawaii, Guam, American Samoa, etc.) and maintains close ties especially with Micronesia through Compacts of Free Association with the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau. These compacts provide economic assistance and other benefits in exchange for exclusive U.S. military access to the signatories’ territories, making them extremely important for the U.S. As noted earlier, China’s actions have stoked U.S. concerns.

The U.S. hosted summits with the Pacific Islands in Washington in 2022 and 2023. It has announced plans to expand diplomatic relations by increasing the number of embassies in the Pacific Islands and has also released a region-specific strategy. It even opened an embassy in the Solomon Islands, which has close ties with China. Massive amounts of funding were also pledged for the Pacific Islands at these summits.

In June 2022, together with the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, and New Zealand, the U.S. launched the “Partners in the Blue Pacific (PBP)” framework to support the Pacific Islands and coordinate closely to maintain the region’s prosperity and security. However, the PBP has been criticized as merely using the “Blue Pacific” label for major powers’ own interests while disregarding the decision-making processes of Pacific countries.

Flags of the Marshall Islands and the United States (Photo: U.S. Secretary of Defense / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

The Pacific Islands and regional powers

Next we look at the relationships of Indonesia, geographically close to the Pacific region, and Australia, a Pacific country itself, with the Pacific Islands. Although both are geographically very close to the Pacific Islands, their political relationships differ markedly.

First, Indonesia. Located in Southeast Asia, Indonesia borders the Pacific and is geographically very close to the Pacific Islands. However, it cannot be said to be capitalizing on this geographical advantage. The reason lies in the conflict between the central government of Indonesia and West Papua.

After World War II, a referendum on independence or integration into Indonesia was finally held in the 1960s in West Papua, a former Dutch colony. Indonesia pressured the people of West Papua to favor annexation, and West Papua was absorbed into Indonesia. Due to this history, an independence movement has continued for decades in West Papua. Several Pacific Island countries (including Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, and Tuvalu) openly support West Papuan independence, and tensions with Indonesia have persisted.

Even under these circumstances, Indonesia has sought to strengthen ties with the Pacific by hosting the Indonesia–Pacific Forum for Development in December 2022. For Indonesia, the Pacific Islands occupy an important position in its geostrategic calculations and face similar climate risks, so building good relations is a key task.

The Indonesia–Papua New Guinea border (Photo: Marwan Mohamad / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Finally, we turn to Australia, the major Pacific power and a member of the PIF.

In Australia’s relationship with the Pacific Islands, its massive economic assistance stands out. According to data from the Lowy Institute, Australia ranks first by a wide margin in total assistance over the entire data-collection period (2008–2021). In particular, it provides loans to address severe infrastructure shortages in the Pacific Islands.

On climate change, there are tensions between Australia and the Pacific Islands. While the Pacific Islands are highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, Australia is a major exporter of the fossil fuels (coal and liquefied natural gas) that drive greenhouse gas emissions. In 2023, Australia was the world’s second-largest exporter of both coal and liquefied natural gas. Since these exports underpin Australia’s economy, it is thought to be difficult to reduce them. The Pacific Islands have repeatedly called on Australia to take effective measures. At the PIF Leaders’ Meeting mentioned above, they also urged Australia to rein in fossil fuel subsidies and cooperate in the fundamental phase-out of fossil fuels.

Among Australia’s recent major moves is the conclusion of the Falepili Union Treaty with Tuvalu announced in 2023. This treaty is Australia’s own response to climate change, the main content of which is to accept Tuvaluans, who are suffering severe impacts from climate change, with special treatment. The treaty would also allow Australia to exercise a veto over Tuvalu’s military agreements with other countries. However, after a change of government, Tuvalu’s new administration has argued the treaty could infringe on Tuvalu’s sovereignty regarding security and is seeking to have Australia reconsider.

Tuvalu, highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change (Photo: UNDP Climate / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Beyond the four countries covered so far, many others—including India, South Korea, Japan, and the EU—are deepening ties with the Pacific Islands for various reasons. Amid fierce competition to build good relations with the Pacific, the Pacific Island countries are asking partners to prioritize the region’s own priorities. Conversely, there is also a view that by skillfully leveraging this competition, the Pacific Islands can choose their partners and exercise agency over a range of options.

What is the future of the Pacific Islands?

An agreement has been reached on the method of selecting the PIF Secretary-General, which triggered the Micronesian countries’ withdrawal move in 2021. However, many other challenges remain for the Pacific Islands. In particular, climate change is an urgent issue; in March 2024, the PIF Secretariat submitted a written statement to the International Court of Justice on states’ responsibilities regarding climate change.

While this article has mainly covered the politics of already independent countries, as noted earlier, there are several territories in the Pacific that have yet to achieve independence. In particular, in New Caledonia, a French territory, tensions are escalating between the Indigenous Kanak and the descendants of former settlers, with France moving to amend its constitution to expand the franchise for French-origin residents in New Caledonia, prompting Kanak demonstrations and clashes and even riots.

We will need to keep a close eye on which path the Pacific Islands take and whether they can conduct region-led politics.

※1 As of June 2024, Australia, Kiribati, the Cook Islands, Samoa, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Tonga, Nauru, Niue, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, Palau, Fiji, French Polynesia, the Marshall Islands, and the Federated States of Micronesia are members; Tokelau and Wallis and Futuna are associate members. The Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Timor-Leste, and American Samoa participate as observers.

※2 Disappointed with the outcome of the February 2021 PIF Leaders’ Meeting, the Micronesian countries that declared withdrawal had each proceeded with their withdrawal processes over the following year. In fact, the withdrawal procedures of the Federated States of Micronesia in February 2022 and of Palau and the Marshall Islands in March were set to take effect on schedule.

Writer: Ayane Ishida

Graphics: Koki Morita, Mayuko Hanafusa

前回の記事を見返しながら、今回の記事を拝見しました。

太平洋諸国の変遷と、最新の状況が分かりやすくまとめられており、理解しやすかったです。

依然としてPIFではゴタゴタが続いているようですが、地域成長と存続のため、地域大国も巻き込みながら諸問題の解決に向かって欲しいと思いました。