In May 2023, armed clashes broke out in Manipur state, located in northeastern India, between members of different communities. Since then, the situation has escalated and many people have been forced to flee. Three months later, at least 120 deaths had been confirmed, and some assessments suggest the real number is even higher. Nevertheless, the Indian government’s response has been criticized as slow.

Such circumstances are not limited to Manipur. Other parts of Northeast India have also seen armed conflict that has continued for many years. Conflicts in this region involve neighboring countries, and instability spills across borders. Why are these conflicts occurring, and what lies behind them? This article explores these questions.

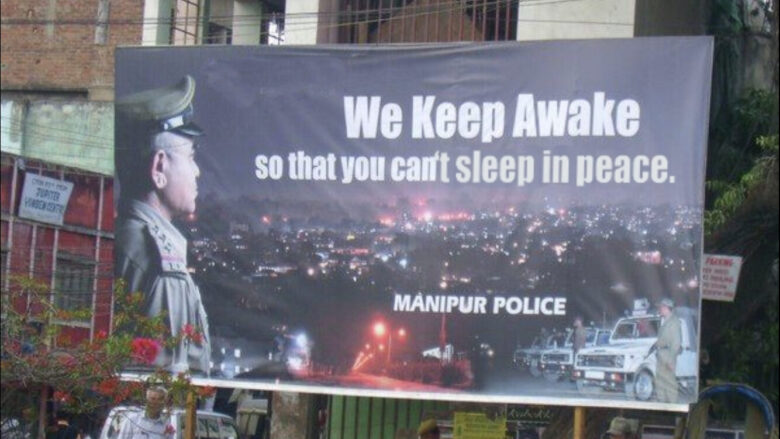

Police in Manipur (Photo: kh n_lyn / Flickr[CC BY-NC 2.0 ]

目次

What is Northeast India?

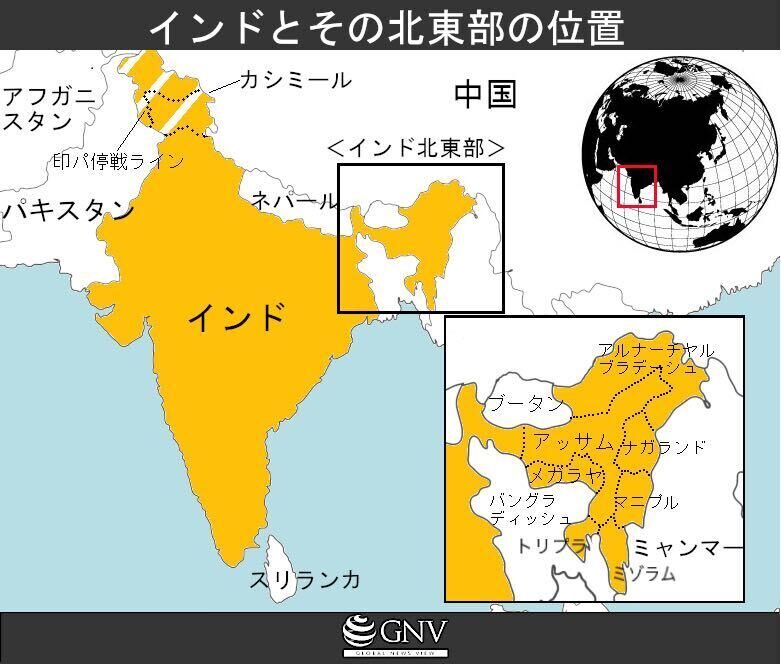

Northeast India consists of seven states: Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, and Meghalaya. The region lies mainly to the east of Bangladesh and west of Myanmar, and also borders Bhutan, China, and Nepal—five countries in total. Although it may look like an exclave, it is connected to the rest of India by the narrow Siliguri Corridor in West Bengal.

Geographically, mountains, hills, basins, plains, rivers, and flatlands are intricately interwoven. More than half of the Northeast is covered by forests, rich in various tree species and biodiversity. Surrounded by abundant nature, agriculture has long been practiced. On the other hand, its geographic separation from the rest of India and its mountainous terrain have made the movement of people and the transport of goods difficult. Underdeveloped inter-regional linkages have hindered the overall regional economic development of Northeast India.

This region is distinctive within India not only geographically. Over 50 million people live here, and the region has languages, cultures, religions, and histories that differ from the rest of India.

In terms of languages, multiple languages from multiple language families are used. Languages that are minorities in India as a whole are central in the Northeast. Assamese is used primarily in Assam, Manipuri primarily in Manipur, and so on—usage is somewhat concentrated by state. However, languages that developed independently exist in various places, making the region a linguistic mosaic due to the sheer number of languages. Ethnic identities are likewise diverse. Community affiliation is often defined by language, and in many cases the name of the language and the name of the ethnic group are the same. Religiously, the region is also distinctive: most Christians in India are concentrated in the Northeast, and the large number of Muslims in Assam also stands out within India.

How anti-government sentiment arose in Northeast India

Next, let’s briefly review how this region known as Northeast India developed historically. As noted above, various ethnic groups formed in what is now the Northeast, and kingdoms and other political formations developed. That changed significantly with the advance of the British. It began when the British East India Company, a trading company, arrived and began to occupy the area from the 16th to the 17th centuries. From 1858, what are now India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh were formally colonized as the British Indian Empire. The Northeast was no exception and was placed under British rule.

Specifically, the Assamese region was divided, as elsewhere in India, into two modes of governance: directly ruled areas under officials from the metropole, and indirectly ruled areas governed through local powerholders. The former covered plains suitable for exploiting natural resources and cultivating crops such as tea. The latter, alongside being designated autonomous areas, also served as a buffer zone for the British against other powers like China. By creating invisible, artificial boundaries, the British effectively segregated parts of the Northeast within India. This sense of isolation is thought to have raised the region’s aspiration for independence.

Even after India’s independence in 1947, the Northeast tended to be treated much as it had been during colonial times, and the region’s political aspirations were often overlooked. This can be seen, for example, in how the rule of law was applied by the Indian government. Citing the need to maintain law and order, the Indian government enacted the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) across much of the Northeast, granting the Indian armed forces special powers to arrest and detain with relative freedom. From a human rights perspective, this has been criticized at times. In addition, the North Eastern Council (NEC) was established to ensure the region’s security and promote political, social, and economic development. Although intended as a policy to aid regional development, it was also perceived as deliberate oversight and intervention by the central government in the Northeast’s autonomy.

Soldiers photographed in Manipur (Photo: lecercle / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

At the root of anti-government sentiment among some people and inter-community tensions lie the geographic and cultural marginalization from the rest of India described above. As a result, poverty stemming from inadequate attention to economic development and social infrastructure needs, and responses by the British rulers and later the Indian government, also played a role. There was also a strong sense among residents that the central government might infringe upon the cultures and ways of life their communities had built, according to some commentary. Over decades, this created conditions that amplified region-wide grievances. Through various processes, insurgent organizations emerged and resorted to violence, while conflicts and clashes also erupted within the region. Below, we look at three states and influential insurgent groups that arose under such circumstances.

Assam

Anti-government sentiment in Assam arose from fears about immigration. During the 1971 war of independence that led to Bangladesh’s separation from Pakistan, refugees in the millions poured into Assam. Some Assamese youth, feeling that the influx posed a serious threat to Assam’s cultural, political, and economic life, launched a movement demanding expulsion. Around the same time, the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) was formed with the goal of freeing Assam and the Assamese people from the shackles of “Indian imperialism” (Note 1). Arguing that Assam’s development lagged despite its rich natural resources, led by major industries such as tea and oil, because these were being exploited by the Indian government, ULFA stoked anti-government sentiment among Assamese people.

In 1983, inspired by those who prioritized Assamese national identity, a popular movement launched a large-scale boycott of the Assam state assembly elections. The boycott involved ULFA and other armed groups seeking Assam’s independence, escalated into violent incidents across the state, and even led to the massacre of Muslims believed to have come from Bangladesh. ULFA rose to prominence amid this series of election-related developments.

However, in the 1990s, armed actions, arms and narcotics smuggling, and extortion intensified, and the group carried out indiscriminate violence such as bombings that also harmed local residents, causing its popularity among Assamese people to decline. As power in ULFA became concentrated at the top, activists grew dissatisfied with the leadership’s authoritarianism, and active participation dwindled. Public support gradually eroded, and ULFA’s call to boycott the 1999 parliamentary vote was ignored.

Tea cultivation in Assam (Photo: Rita Willaert / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0 ])

In 2023, the Indian government reached a peace accord with the pro-talks faction within ULFA. However, the hardline faction did not join the agreement, so there is still no end in sight to the decades-long insurgency.

Nagaland

Many people who identify as Naga once lived within Assam state, inhabiting specific hills and mountain ranges in what is now Nagaland. For centuries they maintained relative isolation—geographically and culturally—from people who lived mainly in the plains. Even British missionaries, who advanced as part of colonial rule, interfered less here than in other regions.

British forces promoting colonization across the Indian region faced strong resistance here. In 1918, the Naga Club emerged as a political forum to establish unity and friendship among the Naga people. Around this time, the British took actions that seemed to promise future independence for Nagaland. After World War II, further unity was achieved, and in 1946 the Naga National Council (NNC) was formed.

The NNC, unwilling to join the Indian Union, concluded the Hydari Agreement with the Governor of Assam two months before India’s independence in 1947. This agreement ensured a certain degree of NNC autonomy and stipulated that after 10 years the NNC could demand an extension of the agreement or the establishment of a new one.Regarding this 10-year period, the NNC interpreted it as meaning that the Naga people’s participation in the Indian Union was temporary. However, the Indian government did not view the review after 10 years as implying the Naga people’s secession from the Indian Union. This disagreement in interpretation led NNC members to feel their demand for independence was being ignored, deepening distrust of the Indian government.

On the eve of Indian independence, a radical faction that split from the NNC boycotted the declaration of Indian independence. The Naga people also signaled their rejection of the Indian Constitution in nonviolent ways by boycotting the post-independence general elections. The Indian government’s response toward NNC members, however, was military action. Naga groups responded with an armed uprising, leading to confrontation with Indian security forces and to conflict.

Mountains in Nagaland (Photo: ILRI / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 ])

In 1963, amid a reorganization of states in the Northeast, Nagaland was formally established as a separate state from Assam.

Despite pressure from the Indian government, underground activity continued and in 1980 the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) was formed, growing into a central force in the Northeast insurgency. In 1988, however, internal differences over peace talks with the Indian government led to a clear split into factions, further clouding the path toward a statewide peace process in Nagaland.

In 2015, several Indian soldiers were killed in an ambush by an insurgent group composed of Naga people, and in retaliation Indian special forces killed members of the insurgent group. In 2021, the same unit mistakenly attacked civilians, causing widespread unrest. Naga society still bears grudges toward the Indian government, and progress toward peace remains uncertain. Even so, some Naga insurgent groups are now seeking peace through negotiations to resolve the political issues the Naga people have long faced.

Manipur

Before colonization, what is now Manipur was an independent state under the Meitei kingdom. It later became part of the Indian Union and a state. During this period, despite invasions by Burma and becoming a (Note 2) princely state under British protection, it retained a degree of autonomy. However, in 1947 it was forcibly merged into India. Many local residents strongly resisted this and asserted separatism. In this region, which comprises multiple communities with various beliefs and cultures, there were conflicting demands and claims toward the Indian government, and insurgent forces emerged accordingly. For example, the United National Liberation Front (UNLF) in 1964 and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1978 are among the armed groups that arose and clashed with Indian security forces.

The conflict cannot be simplified as India’s central government versus Manipur. In particular, there is a tendency toward division between the Meitei people, who mainly live in the lowlands, and the Kuki people, who mainly live in the highlands. One cause is the imbalance in land rights between these communities. Upon annexation to India, the state government designated protected forests in hill areas where many Kuki people live and undertook surveys of Kuki villages within these forests. Many were judged to be below the government’s desired environmental standards, and Kuki people were forcibly evicted. In addition, Meitei people are restricted from purchasing land in the hills, creating a system of current land imbalances between communities.

Manipur’s rich natural environment (Photo: Nick Irvine-Fortescue / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0 ])

Because of the land imbalances described above and distrust of state government actions, there has been constant tension between the Kuki and Meitei communities. That tension escalated into violence in May 2023. On that day, a court handed down a ruling granting the Meitei people a special status under the Indian Constitution. Some Kuki people opposed this and staged protests. The Meitei community was galvanized, and elements within both communities triggered violent clashes. Many people were displaced and killed, and even sexual violence has been reported. The Indian government was also criticized for remaining silent for about two months after the violence in Manipur became overt in May 2023. Soldiers and police have been deployed to the region, but the communities’ longstanding anxieties remain.

A look across the Northeast

So far we have focused on three states in Northeast India, but insurgent organizations like those described above have also appeared in other parts of the Northeast, such as Mizoram and Tripura. In Mizoram, when a large-scale famine struck the Mizo Hills in 1959, some Mizo people formed a support organization to save those suffering in place of the government. Reflecting discontent with the Indian government in the Mizo region, they later espoused separatism, and in 1966 began operating as the armed Mizo National Front (MNF). In Tripura, the National Liberation Front of Tripura (NLFT) also developed as an anti-government force in 1989. The group seeks to expel Bengalis and Bangladeshis who have migrated to Tripura since the 1970s as refugees and to make Tripura an indigenous state independent from the Indian government. However, numerous civilians have also been victims.

Thus, the presence of insurgent groups is not limited to relatively large organizations like the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NCNS) and the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA); they can be found across the Northeast. Among people with distinct ethnic identities, some demand national independence or autonomy and have organized themselves. Their demands have been directed at the central government, sometimes peacefully and sometimes violently.

The Northeast has unique geographic conditions, lagging development, and some of the greatest cultural diversity within India. Inequalities between communities and differential treatment by the government have increased the likelihood of inter-community clashes and anti-government sentiment. Moreover, the Indian government did not show willingness to address the concerns and demands of these communities. On the contrary, it often treated the Northeast separately from the rest of India and sought to suppress discontent by force. Tending to view it as a potential national security threat, the government bound the region with laws and justified top-down interventions and the use of force. Such responses likely contributed to distrust of the government and turmoil across the Northeast as a whole.

Everyday life in Manipur (Photo: lecercle / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 ])

Relations with neighboring countries

Northeast India has deep ties with India’s neighbors due to geographic and cultural proximity, and there are ethnic groups that straddle national borders. Thus, there is grassroots exchange and trade. However, there is also friction from the perspective of each country’s interests and calculations, and it is noteworthy that different actors engage with insurgent groups in various ways.

China and India have been at odds over their border since the 1950s, and in 1963 the dispute escalated into war in the Himalayas, ending in a ceasefire after about a month. Their territorial dispute dragged on for decades, and in the latter half of the 20th century there was a pattern of each side supporting insurgent forces in the other country. In the past, the Chinese government, which has long had an interest in the Himalayas, supported Naga insurgents by training them in parts of China, while insurgents in Tibet, who began by resisting the Chinese government, received support from the Indian government.

China also continues to claim Arunachal Pradesh in Northeast India as part of its own territory, referring to it as South Tibet. Furthermore, in 2021, China announced standardized names in Chinese characters and Tibetan script for several places in the state, to which the Indian government expressed displeasure.

Pakistan separated from India in 1947, and the two countries clashed over the status of Kashmir. After ceasefire talks, parts of the region effectively came under the control of India and Pakistan (and partly China), and the dispute continues. Amid this tension, Pakistan took note of the activity of anti-Indian insurgent groups. Through its Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), Pakistan provided training and financial support to Naga insurgents and cooperated with the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA), which sought to expand its capabilities by establishing bases outside India. Pakistan’s aim appears to have been to foment unrest in parts of India other than Kashmir in order to reduce pressure on Kashmir.

On the India–Bangladesh border (Photo: Prabhat114 / Flickr [CC BY-SA 4.0 ])

Bangladesh received support from India during its 1971 independence from Pakistan. However, the conflict led to an influx of refugees into Northeast India. Many of them were Muslim, which concerned the Indian central government. Among residents of Assam, a stereotype took hold that the influx of refugees seized Assamese land and succeeded economically, and movements arose calling for their expulsion. In 1983, an incident occurred in which more than 2,000 Muslim settlers were killed over roughly six hours; many of the victims were said to be from Bangladesh. Meanwhile, territorial issues after independence worsened relations between the two countries, and each began aiding insurgent groups within the other’s territory (Note 3).

Myanmar has had relatively little conflict with India, partly because it has many domestic problems of its own. However, under military rule and in an unstable Myanmar, insurgent forces from Northeast India have been building strength to survive. Taking advantage of geographic proximity, several active insurgent groups that have refused peace with the Indian government have established bases in Myanmar.

In 2019, insurgent camps from Northeast India located in Myanmar’s Sagaing Region were destroyed by the Myanmar military, which seemed like good news for the Indian government. In 2021, the two countries agreed that neither would allow its territory to be used for harmful activities. In practice, however, there have been reports that the Myanmar military and some insurgent groups from Manipur reached a secret understanding to cooperate.

Moreover, the 2021 coup in Myanmar and the subsequent intensification of conflict between the junta and insurgents triggered an influx of refugees from Sagaing—which has strong ties to the Kuki community—into India. This greatly alarmed the Meitei community and deepened the divide between the two communities.

As for Bhutan–India relations, while insurgents from India have hidden in this area and established bases that the Bhutanese government could not fully deal with, ties are considered better than with other neighbors of Northeast India. However, there are also claims that insurgents have engaged in illegal logging and poaching in the cross-border forests to fund their activities while moving toward bases in Bhutan. They are also said to have operated within protected forests. From the perspective of restoring degraded protected forests and conserving soil, counterinsurgency in this area is important for nature conservation as well.

A church in Nagaland (Photo: Kandukuru Nagarjun / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Conclusion

As we have seen, Northeast India faces a complex situation in which various problems are intertwined: confrontation with the Indian government, conflicts between ethnic communities, and mutual interference with neighboring countries. The presence of insurgent groups is significant, and ordinary people continue to face life-threatening instability. Although the situation is complex, we hope that each community in each region, the Indian government and neighboring countries, and the parties themselves will understand what is desired and move little by little toward peace.

Note 1: Many other insurgent groups have emerged in Assam. Examples include the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) and the Kamtapur Liberation Organization (KLO) groups, and the Muslim United Liberation Tigers of Assam (MULTA) in areas where immigrant Muslims reside groups.

Note 2: A princely state was a local regime that, while under British colonial rule in India, was granted a certain degree of autonomy.

Note 3: The India–Bangladesh border with West Bengal had long contained enclaves, which became an issue after Bangladesh’s independence. Although an agreement was once reached to exchange or cede enclaves, the territorial issue hardened due to India’s refusal. Relations further deteriorated when Bangladesh declared itself an Islamic state. Since 2014, there have been signs of rapprochement between the two countries over the territorial issue.

Writer: Rei Oishi

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

国境も地形も入り組んだ場所に言語もアイデンティティも異なる多くの人々が住んでいるので紛争が絶えないですね……ここでも過去の植民地支配が原因の一つになっていて、植民地支配の有害さをひしひしと感じます。