The citizenship of 4 million people living in India is at risk. On July 30, 2018, the Government of India released the National Register of Citizens (NRC). It turned out that 4 million residents of northeastern India had been removed from the register. The NRC lists those who can prove they were residing in India up to March 24, 1971. Why did the Indian government set such a condition? We delve into the issues facing northeastern India that lie in the background.

Polling station in India (Photo: Public.Resource.Org/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

The immigration issue in the background

In the NRC episode mentioned at the outset, those erased from the list were people from India’s northeast. Why were people in this region targeted? One reason is the immigration issue the northeast faces.

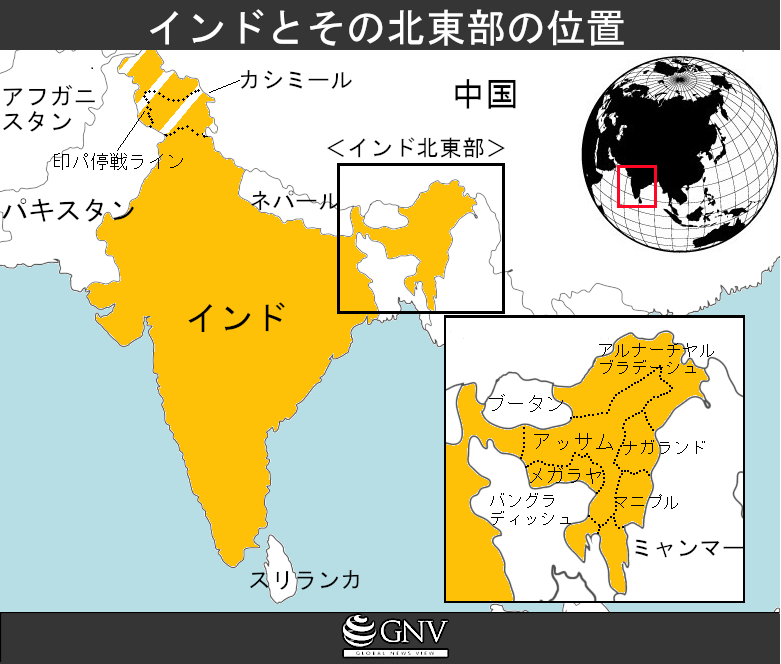

The troubled northeastern region borders Bangladesh, where Muslims are the majority, and Bhutan, where Buddhists are the majority. Given this geography, northeastern India has historically seen large inflows of migrants. In the 19th century, under British colonial rule, population movements to the northeast were organized to secure labor for tea plantations, both from within India and from abroad. In particular, migrants from East Bengal (Note 1) brought agricultural skills and knowledge that significantly influenced agricultural production in the northeast. In 1947, India and Pakistan became independent as separate states, but Bangladesh at that time belonged to Pakistan as “East Pakistan.” When millions of migrants flowed into India from East Pakistan, the first National Register of Citizens was drawn up in 1951.

The situation worsened in 1971. That year, East Pakistan broke away from Pakistan and Bangladesh was born. The intense war of independence produced many refugees, and many fled to northeastern India. In Assam, the sharp rise in immigration sparked anti-immigrant riots from the late 1970s to the early 1980s, deepening the divide between people who had long lived in the northeast and migrants. This struggle, known as the “Assam Movement,” ended in 1985. The Government of India and the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) reached an agreement, under which those who had moved to India after March 1971 would be deemed “foreigners.” The 2018 NRC episode is thought to have these issues as its backdrop.

The 2016 Citizenship Amendment Bill

There is another important policy related to India’s immigration issue: the 2016 Citizenship Amendment Bill. Under the amendment, among illegal immigrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, those who are Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Zoroastrians, or Christians would be granted citizenship. In the end, the bill was scrapped in 2019 before it was passed by Parliament, but it sparked widespread debate across India.

Why did the Indian government push this amendment? The government argues that the bill’s purpose is to aid people persecuted in their home countries for religious reasons. Muslims are not included among the eligible groups on the grounds that in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, Islam is the majority religion and Muslims would therefore not be persecuted there.

The government also says that by passing this bill, it aims to prevent Assam from becoming a “second Kashmir.” In 1947, when India and Pakistan gained independence from Britain, they became independent as a majority-Hindu India and a majority-Muslim Pakistan. The princely state of Kashmir, where most of the population was Muslim but the ruler was Hindu, acceded to India. Under these circumstances, war broke out between India and Pakistan over Kashmir, and in 1972 a “ceasefire line” was established between the two countries, dividing Kashmir into Indian-administered and Pakistani-administered areas. However, the conflict between India and Pakistan in the region continues today. Moreover, anti-India forces also exist within the Indian-administered area of Kashmir. Since 1989, attacks by anti-India groups have occurred, and 70,000 people have lost their lives. Pakistan is said to support these forces, and at times this has escalated into military clashes between India and Pakistan.

India’s Border Security Force guarding the border with Bangladesh (Photo: Patho72 / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Officials argue that a similar problem could arise in northeastern India—namely, that it could develop into a struggle with anti-government forces, as in Kashmir. In 1971, the share of Hindus in Assam was 71%, but by 2011 it had fallen to 61%. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) also worries that a decline in the Hindu proportion could reduce the number of seats it can win in the state.

Contradictions lurking in the amendment bill

Despite the government’s claims, critics say the bill contains contradictions. The government says the bill aims “to rescue people persecuted in their home countries.” However, it has been pointed out that the government may be arbitrarily limiting who is to be helped. As noted above, citizenship would be granted only to migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan, where Muslims are the majority. Yet there are many migrants and refugees from Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar, and the government excludes them from protection. In particular, a Muslim minority from Myanmar known as the Rohingya has faced persecution, become refugees, and fled to India. They have been described by the UN Human Rights Council as “the most persecuted minority in the world.” Nevertheless, the Indian government excludes them from protection under the amendment bill. What’s more, in January 2019 it arrested several Rohingya refugees and detained them for 14 days.

In light of this, doubts remain as to whether the Citizenship Amendment Bill was truly created “to protect migrants and refugees.” These moves are thought to stem from the ideology of the ruling BJP, which is said to be effectively promoting Hindu supremacy. Some have argued that by advancing such policies, the BJP is trying to exclude Muslims from the country and realize a “Hindu nation.”

Prime Minister Modi delivering a speech (Photo: Narendra Modi/Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

It has also been suggested that through this amendment bill, the government is trying to prevent Muslims from becoming a majority in the northeast. As noted at the outset, 4 million people were struck off the list in the NRC episode. In fact, of those 4 million, 2.2 million were Hindus. The government appears to be seeking, via the amendment bill, to grant citizenship to Hindus who were excluded from the NRC. In that sense, the bill can be seen as a measure that favors Hindus.

Public protests

As seen above, the Citizenship Amendment Bill contains many contradictions. There were also many voices of opposition from residents of the northeast, but their objections were not about these “contradictions.” Why did so many residents oppose the bill? Unlike the government, which appears to emphasize religious differences, local residents do not necessarily prioritize religion. Several BJP members in Assam also oppose the government’s stance. They take the position that “citizenship should not be granted to foreigners regardless of religion.” Rather, they fear that accepting migrants and refugees will intensify competition over land rights and jobs. In addition, there is concern that the bill will increase the number of Bengali speakers. With rising immigration, residents fear they will become a “minority” in the northeast, and they worry about this prospect.

Guwahati, Assam (Photo: Max Pixel [CC0 1.0])

Citizens’ demands and the government’s intentions at cross-purposes

As we have seen, the Indian government is trying to push policies that emphasize “Hindu identity,” ignoring the voices of local residents. Although the policy may appear to protect migrants and refugees, it is clearly not truly aimed at their protection. As the government’s aims diverge from those of local residents, anti-immigrant sentiment on the ground is only growing. Although the Citizenship Amendment Bill was scrapped this time, concerns about it have not disappeared. That is because general elections for the lower house will be held from April to May 2019. If the BJP wins a majority in this election, the bill is likely to resurface. What will become of the citizenship of 4 million people? And will the conflict between migrants/refugees and local residents in the region be resolved? We should watch developments closely.

Note 1: East Bengal is present-day Bangladesh. Before India’s independence in 1947, East Bengal and India were both under British rule as part of British India.

Writer: Tomoko Kitamura

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

年末の10大記事の中にありましたね!気になっていたので読めてうれしいです!

表面的には移民保護政策に思える政策が、裏の意図を理解しないまま進められていく怖さを感じた。日本にもそのような法案が存在するのかしら?

「ヒンディー・アイデンティティ」の言葉や「アメリカファースト」のように、何かを◯◯国民のアイデンティティとして結びつけるイデオロギーが増えているように感じるが、グローバル化が進み、様々な人々の行き来が活発化し、流動的になる世の中において、そのような排斥精神は時代に逆行しているように感じる。

国民の声、国益、時代の流れ、何を考慮して政治の舵を切るのかに正解はなく非常に難しいと思った。

宗教対立は政府や上の者が思うほどではなく、市民達は案外穏やかに暮らしているのかなとも思いました。それにしても、人口の多い国はこういう統制が大変なのですね。

移民問題、領土戦争、宗教対立。国家は様々な背景要因を考慮してルールを制定するのだから、表向きの目的や背景を鵜呑みにしてしまう怖さを感じました。

また、国を動かす人間と実際に問題に直面する住民との間にある認識の乖離は、本当に難しい問題なんだと再認識させられます。それぞれがそれぞれの課題意識や感情を持っているはずで、簡単には「共感」できないだろうけれど、しっかりと向き合えば相手の状況を頭で「理解」することはできると思います。このような対立の解決を目指すには、他者に対して真摯に向き合う姿勢が一番大切なのかもしれません。