In 2023, during the hurricane season that runs each year from 6 to 11, the Caribbean region was struck by as many as 20 powerful storms, including 7 hurricanes, causing devastating damage. In light of this, experts at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have described the 2023 hurricane season as one of the most turbulent years on record.

One reason cited for the worsening hurricane damage in the Caribbean is the exceptionally high Atlantic sea surface temperatures driven by climate change. The global warming that drives climate change is caused by greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide. Humans emit greenhouse gases through various activities, with emissions from high-income groups being particularly large. The Caribbean is also one of the world’s leading destinations for ultra-wealthy individuals who tend to have high emissions. At the same time, however, the region experiences widespread poverty. The gap there contributes to a range of problems beyond climate change. This article explores the current situation and challenges facing the Caribbean as it is buffeted by the actions of the world’s wealthy.

Resorts and yachts on St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands (Photo: Scott Smith / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED])

目次

Widening inequality around the world

Before discussing inequality in the Caribbean, let’s look at global inequality first. According to an Oxfam International report on inequality by the UK-based NGO dedicated to ending global poverty and injustice, in 2018 the wealth of the bottom 50% of the world’s population—3.8 billion people—fell by 11%, while the wealth of billionaires with assets totaling over 10 billion USD was growing at a pace of 2.5 billion USD per day. Furthermore, as of 2019, the combined wealth of those 3.8 billion people was equal to that of just 26 of the wealthiest individuals.

Global economic inequality has widened further due to the COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020. In Oxfam International’s 2024 edition of its inequality report, it is stated that since 2020 the wealth of the world’s five richest people has doubled, and billionaires with over 1 billion USD in assets have become richer by 3.3 trillion USD.

While the wealth of the rich has increased, the pandemic has simultaneously accelerated global poverty. According to a World Bank study in 2022, global economic inequality reached its highest level since 1945. In fact, as of 2021, the average income of the bottom 40% of the global income distribution was 6.7% below pre-pandemic projections and had declined by 2.2% between 2019 and 2021. There are also reports that since 2020, more than 5 billion people worldwide have become poorer.

History and overview of the Caribbean

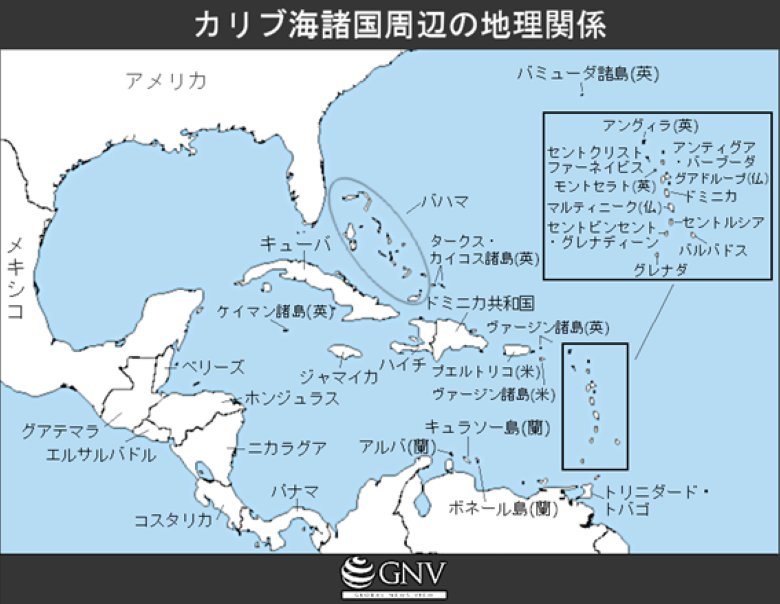

Having looked at global poverty, the Caribbean is one of the regions where poverty is particularly severe. So what kind of region is the Caribbean? The Caribbean is a marginal sea of the Atlantic, located between Central and North America, and is the second largest at approximately 2.7 million square kilometers. The Caribbean region includes 13 sovereign states and 17 territories of countries outside the Caribbean. While there are large islands such as Cuba and Hispaniola, there are also about 7,000 smaller islands scattered throughout.

Next, consider the region’s climate. The Caribbean, which lies in the tropics and is warm year-round, is heavily influenced by ocean currents, mountain elevation, and changes in the trade winds. The hurricane season in this region lasts from 6 to 11, peaking between 8 and 9.

Looking at the region’s economic aspects, tourism is a key part of the economy. With coral reefs and mangrove forests and rich natural features, Caribbean islands attract many tourists—primarily from North America—for beaches and diving. It is home to many major resort destinations and is also a popular relocation spot for wealthy people from outside the region.

Turning to history, many islands were originally inhabited by Indigenous peoples such as the Taíno and Ciboney. From the 15th century onward, European powers including Spain, Britain, France, and the Netherlands expanded into the region. Plantation agriculture, such as sugarcane cultivation, spread rapidly, and alongside the local population many people forcibly relocated from Africa as slaves were forced into brutal labor. In the process, most of the local population died from disease.

Eventually, the Caribbean became a region of European colonies. In the 19th century, however, slave rebellions increased and the plantation system declined. At the same time, European colonial rule began to wane, and by the mid-20th century many island nations had achieved independence.

Yet as many as 17 territories remain under foreign rule, including the British Cayman Islands and Turks and Caicos Islands, the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, and the Dutch island of Curaçao. There are several reasons why these territories have not become independent. For the metropolitan countries, the Caribbean is convenient for military bases and as a tax haven. For the territories, there are benefits such as receiving economic assistance from the metropole and strong attachment among residents—many of whom are from the metropole—to the mother country. In addition, some territories remain economically dependent on the countries that colonized them. It is rare in the world for a region to still host so many territories of European and North American countries.

Flags of the UK’s overseas territories displayed in Parliament Square (Photo: Foreign and Commonwealth Office / Wikimedia Commons [Open Government Licence version 1.0])

Inequality in the Caribbean and wealthy nonlocals

As global poverty worsens, the Caribbean is no exception. The region has large populations living in poverty: in the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Saint Lucia, roughly 30% of the population, and in Haiti, about 90% live below the ethical poverty line (※1) as defined here.

These poverty issues fuel numerous social problems across Caribbean countries and territories. First is high unemployment. For example, according to World Bank data, as of 2022 unemployment stood at 19% in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, 17.4% in Saint Lucia, and 14.8% in Haiti—placing these three among the world’s 30 countries with the highest unemployment. The COVID-19 pandemic also severely damaged tourism, which accounted for a large share of economic activity and jobs, causing job losses in many countries and territories.

Rising crime is also a concern. Some Caribbean countries and territories suffer from weak economies and instability due to corrupt governments, and among the unemployed, some turn to crime to seek income outside legal work. The Caribbean is also a transit point between drug-producing countries in South America—such as for cocaine—and consumer markets in North America, contributing to drug-trafficking–related crime.

Poverty also limits children’s access to education, creating a challenge of low educational attainment. In Saint Lucia, as of 2012, 96% of the wealthy completed primary education, compared to just 62% among the poor. In the Dominican Republic in 2020, among 15-year-olds, the number of students in the poorest group achieving minimum proficiency in mathematics was less than 20% of the number achieving it in the richest group, according to data.

A street scene in Jamaica (Photo: Christina Xu / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED])

At the same time, the Caribbean is home not only to the poor but also to globally influential wealthy individuals. As of 2019, the region had over 1,100 millionaires with assets exceeding 1 million USD, and this number is growing annually. According to Forbes’ 2021 billionaires list, there were 8 billionaires in the Caribbean region, but none were originally from the Caribbean. In 2022, 2 Caribbean-born individuals were added to the billionaires list, yet the share of nonlocals remains high. The behavior of these wealthy individuals, including billionaires, has also been linked to worsening social issues related to poverty, as described above.

Some of the world’s billionaires use their vast wealth to acquire land, with some even purchasing entire Caribbean islands. For example, Richard Branson, founder of the Virgin Group, which operates in industries such as music and aviation, has personally purchased multiple uninhabited islands in the British Virgin Islands.

Wealthy individuals who own Caribbean islands can leverage their money to influence local regulations and legal systems—sometimes even evading the law. For instance, investor Jeffrey Epstein purchased and owned two islands in the U.S. Virgin Islands. He brought underage girls to these islands and engaged in sexual exploitation and sex trafficking. Because of these crimes, the island he owned was dubbed “Pedophile Island.” He was eventually arrested and indicted, but what enabled his crimes to continue for some 20 years was his political influence through political donations.

There are also issues of corruption involving local politicians and power brokers (※2). Examples include Michael Misick, premier of the British Turks and Caicos Islands, who faced bribery and corruption allegations, and Jack Warner, former vice president of the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) and former Minister of National Security in the government of Trinidad and Tobago.

However, the inequality problem is not only visible in the actions of tycoons and power holders living in the Caribbean; it also appears in tourism, which supports the economy. For example, the development of resorts catering to wealthy vacationers and tourists has restricted local fishing activities. In Jamaica, hotel construction for coastal resort development has been frequent, increasing private beaches and leaving local residents with access to just 1% of the coastline. This has negatively affected fisheries, a key industry for the island. One fisherman testified that before resort development began, he could reach the coast with a 10-minute walk from home, but after beaches were closed off by hotel construction, he had to travel about 10km each way to reach the sea for daily fishing. As a result, many people in Jamaica have become unemployed or homeless.

A view of the island owned by Epstein (Photo: Navin75 / Flickr[CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED])

Tax avoidance and evasion by the wealthy

Tax avoidance and evasion issues in the Caribbean involve corporations and tycoons from around the world. The Caribbean—especially British territories—has many jurisdictions considered tax havens. A tax haven is a country or region (※3) that imposes no taxes or very low taxes on foreign companies. Tax havens also typically limit the disclosure of information on locally established companies and their owners, thereby guaranteeing a high degree of secrecy.

Many companies and wealthy individuals around the world that use Caribbean tax havens set up paper companies—entities registered there but with no real business or commercial activity. Numerous cases of tax avoidance and evasion have come to light in which profits are shifted into these entities. Much of the shifted wealth merely passes through the Caribbean, but some wealthy individuals base themselves in Caribbean jurisdictions to exploit these advantages. While using loopholes in tax-haven laws and systems to avoid taxes may be legal, evading taxes and laundering money by exploiting secrecy is illegal.

The Caribbean is one of the world’s major concentrations of tax havens. According to the 2021 Corporate Tax Haven Index published by the UK-based NGO Tax Justice Network, which measures the extent to which jurisdictions enable multinational corporate tax avoidance (※4), the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, and Bermuda had the highest index values. In fact, in the Cayman Islands, the number of registered companies is about 120,000—twice the resident population of 60,000—indicating a very large scale.

Purchase of passports (citizenship) by the wealthy

There is also a problem of wealthy nonlocals abusing passport programs offered by Caribbean nations.

Some Caribbean countries sell their national passports to foreigners. Purchasing such a passport is one of the ways for wealthy nonlocals to obtain Caribbean citizenship. To buy citizenship, one needs only to invest—from several hundred thousand to several million USD—in public assets or real estate in the country offering the passport and undergo a background check only. These second and third passports acquired by the wealthy are known as “golden passports,” and the holders do not even need to reside where they hold citizenship.

By purchasing golden passports from Caribbean countries, wealthy individuals can gain tax advantages and visa-free access to many countries. For example, obtaining a Saint Kitts and Nevis passport exempts one from taxes other than corporate tax and grants visa-free travel to as many as 157 countries, according to reports.

Passport of Dominica (Photo: Mehranvary / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED])

The government of Dominica has sold citizenship and passports to foreigners since 1993. Most passport purchasers are from North Africa, Central Asia, and the Middle East, and according to a 2023 joint investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and the Guardian, since 2007 the number of people who purchased Dominican passports has reached about 7,700, compared with a total population of roughly 70,000.

From these passport sales, the Dominican government has gained an estimated 1 billion USD or more in profits since 2009. However, behind such profits lies an issue whereby even wealthy individuals with criminal records have been allowed to purchase citizenship (※5).

The Caribbean’s wealthy and climate change

The presence of the wealthy is also tied to the severe climate change impacts occurring in the Caribbean. Due to climate change driven by global warming, the frequency of hurricanes in the region may increase.

As the risk of more frequent hurricanes grows, the resulting disaster damage is also becoming immense. For example, as of 2022, the Caribbean has experienced 324 disasters since 1950, with more than 250,000 lives lost. When Hurricane Fiona struck the Caribbean in 2022, massive flooding occurred in Puerto Rico (U.S. territory), requiring the rescue of over 1,000 people. Flooded waterways and power outages caused pump failures, leaving 70% of households and businesses that rely on public water and sewage systems without access to drinking water, according to reports.

Sea-level rise caused by melting sea ice due to global warming is another major climate impact in the Caribbean. If global greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase, the Caribbean’s sea level could rise by up to about 84cm by 2050 compared with 2000. Rising sea levels elevate storm surges, increasing damage to infrastructure from disasters—including hurricanes—in low-lying areas, and heighten the risk of permanent inundation.

A town in the Virgin Islands completely destroyed by Hurricane Irma (Photo: DFID – UK Department for International Development / Flickr [CC BY 2.0 DEED])

One driver of climate change that causes such extreme weather and sea-level rise is the massive greenhouse gas emissions by the world’s wealthy. According to an Oxfam International report, in 2022 the world’s top 125 richest individuals emitted an average of 3 million tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) per person annually through their investments. This is a million times the average 2.76 tons emitted by the bottom 90% by income. These enormous CO2 emissions also stem from the wealthy’s consumption patterns, such as the frequent use of private jets and yachts.

Although the Caribbean is heavily affected by climate change, there are examples of measures being implemented to enhance resilience. In 2017, Dominica’s Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit told the UN General Assembly that Dominica is “on the front line in the war against climate change,” and new policies have been introduced, including reconstruction plans and building codes to create disaster-resilient infrastructure and the promotion of eco-tourism.

However, not all small, low-income Caribbean countries can necessarily implement such measures. There is also the issue of “loss and damage,” where low-income countries—without adequate access to services like infrastructure and healthcare—bear the brunt of climate change impacts caused by greenhouse gas emissions historically produced in large quantities by high-income countries. The situation in which high-income countries and the wealthy have greater capacity to respond to climate impacts while low-income countries and the poor suffer more is referred to as “climate apartheid.”

Development and environmental destruction

In addition, land development—such as building resorts for the wealthy—is accelerating environmental destruction in the Caribbean. For example, in 2017, on Barbuda in the twin-island nation of Antigua and Barbuda in the Lesser Antilles, developers working with local politicians attempted to turn much of the island into an ultra-luxury resort for the rich.

However, the target area for the resort development includes Codrington Lagoon National Park (CLNP). CLNP features lush mangroves, vast seagrass beds, and coral reefs, and functions as a seawall against coastal erosion from hurricanes, making it protected under the Ramsar Convention on wetlands. Nonetheless, mangroves and coral reefs in CLNP have continued to be destroyed by the resort development, and experts have questioned whether the Ramsar Convention is being upheld. Such environmental degradation weakens the island’s soils and becomes a cause of even greater flood risk when future hurricanes occur.

Rough seas off Sint Maarten (Kingdom of the Netherlands) whipped by Hurricane Irma’s strong winds (Photo: Ministry of Defense, Netherlands / Wikimedia [CC0 1.0 DEED])

In addition, the resort development on Barbuda involved land grabs by the wealthy that exploited hurricane damage. In 2017, the major hurricane Irma caused enormous damage on Barbuda—destroying homes, infrastructure, and livelihoods. A state of emergency was declared, and evacuees were made to stay for 30 days on the more populous sister island, Antigua. The resort development on Barbuda proceeded during this absence of residents, thereby avoiding local opposition. Locals on Barbuda have strongly condemned this as a “land grab.”

Conclusion

The Caribbean has a history of colonial rule by European countries and still has many territories that have not gained independence, leaving poor local people at the mercy of high-income countries and the wealthy across generations. While investments by tycoons targeting the Caribbean can indeed stimulate local economies, at the same time the presence of billionaires in the region gives rise to various problems, including environmental issues, tax issues, wealthy individuals’ influence on politics and policy, large-scale land acquisitions and development, and widening economic inequality. Those who bear the brunt of these problems are the local poor.

Moreover, the issues of climate change and tax havens involving the wealthy in the Caribbean are viewed as problems that affect not only the Caribbean but the entire world. It is time to reexamine the role of the ultra-wealthy, whose influence extends well beyond the Caribbean to global social issues.

※1 As of 2019, the World Bank’s extreme poverty line was 1.9 USD per person per day. However, given real living needs, some researchers argue this standard is unrealistic and instead propose an “ethical poverty line,” the minimum income associated with guaranteed survival based on the relationship between life expectancy and income. In 2019 this was 7.4 USD per person per day. GNV adopts this ethical poverty line. However, the World Bank’s data provide poverty rates at 7.0 and 7.5 USD per day only, so we used 7.5 USD as closer to the 7.4 USD ethical line. Data years: Dominican Republic 2021, Jamaica 2004, Saint Lucia 2016, and Haiti 2012.

※2 In the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) published annually by Transparency International, Caribbean countries have ranked low over the past 10 years, and in some countries political corruption has worsened.

※3 Reasons countries or regions become tax havens include offering tax incentives to attract foreign companies and to facilitate profit shifting. In addition to boosting economic activity through the transactions of these established or relocated companies, jurisdictions can earn revenue from fees charged during company relocation or incorporation.

※4 Published by the Tax Justice Network, this combines two indicators: the extent to which a jurisdiction’s tax-haven laws can be abused by companies and investors, and the share of global activity using the tax-avoidance facilities hosted by that jurisdiction.

※5 Turkish businessman and former government minister Cavit Çağlar was arrested in 2001 in connection with fraud related to Interbank. He subsequently obtained Dominican citizenship in 2011 despite regulations that should bar applicants with criminal records.

Writer: Mayu Nakata

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

カリブ海諸国についてタックスヘイブンの問題や環境問題など少しは理解していたつもりでしたが、富裕層たちによるパスポート(市民権)購入については全く知らずとても驚きました。ゴールデンパスポートについてもう少し調べてみようと思いました。