On 2023–10–1, in Albania, a law took effect obliging medical students to work in the country for up to 5 years before obtaining their degree. Students who do not agree to this obligation are required to cover the full, hefty tuition costs themselves, but the exact amount is not specified in the law. Many Albanian medical students oppose this law and have protested, and it is currently awaiting a ruling on its constitutionality by the Constitutional Court.

The government says the law was created to prevent the outflow of medical students abroad (Note 1). However, this conspicuous exodus is not limited to medical students. Albania’s population has been declining since the 1990s and continuing to the present day. Since the collapse of the communist system in 1991, some 40% of Albania’s population has emigrated. Why is this happening? This article looks in detail at the problems the country faces while reviewing Albania’s history.

Inside a hospital in Patos, Albania (Photo: HAP Project / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED])

目次

From Independence to the Birth of the People’s Republic of Albania

The region of present-day Albania has experienced rule by various powers, including the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, and the Ottoman Empire. In November 1912, after nearly 5 centuries under Ottoman rule, Albania declared independence. At the time, the 1st Balkan War (Note 2) was raging in the Balkans. In December 1912, the London Conference was convened to negotiate the division of Ottoman territories after its defeat and to decide the future of Albania, which had declared independence during the war. At this conference, under the supervision of the Great Powers, it was formally decided to establish the Principality of Albania as an independent sovereign state (Note 3).

At that time, under pressure from Greece and Serbia, half of the territory claimed by the Albanian side was excluded from the Principality of Albania, leaving about 30–40% of ethnic Albanians outside the principality. For a century after independence, borders shifted, and even today people who identify as ethnic Albanians live in many countries, including Kosovo (Note 4), Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Greece. Notably, in Kosovo—one of the territories claimed by the Albanian side at the London Conference but not recognized—the population is 92% ethnic Albanian. The area then underwent changes of political system from the monarchical Principality of Albania, to the republican Republic of Albania, and then to the Kingdom of Albania. Ahmet Zogu of the Zogu family, which had held the governorship of the Mat region under the Ottomans, served as Prime Minister of the Principality, President of the Republic, and King of the Kingdom of Albania.

Albania’s location has historically been of geopolitical value to many powers. Before independence, the present capital Tirana lay on the straight line connecting present-day Istanbul—capital of the Byzantine and Ottoman empires—and Rome, placing it at the crossroads of East and West, and Albania’s position on the eastern side of the gateway from the Mediterranean into the Adriatic exposed it to many cultures and foreign interests. With these features, Albania continued to attract foreign attention after independence. In 1939 it was annexed by Italy, and in 1943 it was occupied by Germany.

Religious affiliation has also been influenced by historical rule. Under the Romans and Byzantines, most people in Albania practiced Christianity, but under Ottoman rule Islam became the main religion. In 2011, about 59% of the population identified as Muslim and about 17% as Christian.

In 1941, under the Yugoslav Communist Party, which was leading an anti-fascist (Note 5) movement, a communist party was established in Albania. Its First Secretary was Enver Hoxha. Party members fought as communist partisans against Italian and German rule. When Italy surrendered to the Allied forces in 1943 during World War II, its control over Albania collapsed. In October 1944, following the Yugoslav communists, a parliament was established and a new government was born. In November of the same year the whole of Albania was liberated. In 1946, the convened parliament declared the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the People’s Republic of Albania.

Enver Hoxha’s Dictatorship

From the formation of the provisional government in 1944 until his death in 1985, for some 40 years, Hoxha’s Communist Party of Albania (later the Party of Labour) ruled the People’s Republic of Albania as a dictatorship. Hoxha was a staunch supporter of Joseph Stalin, then the supreme leader of the Soviet Union, and embraced Stalinism (Note 6). The Soviet Union, the world’s first socialist state, supported Albania’s communist regime—born during World War II—economically and ideologically. Hoxha introduced a Soviet-style industrialization program, sought to improve living standards, and worked on improvements in areas such as health care, education, and women’s rights.

At the same time, the Party of Labour began to intervene in citizens’ daily lives. Private property was banned, food was distributed by rationing, and restrictions were imposed such as requiring newborns’ names to be chosen from a government-approved list.

Hoxha also grew increasingly extreme and paranoid over time and began using the security apparatus. At its center was the organization known as Sigurimi, the secret police that cracked down on dissidents. Sigurimi is estimated to have executed more than 6,000 people during the communist era, and to have investigated, persecuted, sentenced to life imprisonment, and interned thousands in inhumane prisons and camps. Declassified documents show that in the capital Tirana alone, about 4,000 people were under Sigurimi surveillance, with between 3 and 50 informants assigned to each family under surveillance. Hoxha executed not only those who challenged his rule and their collaborators, but even rivals within his own party. In this way, over roughly 40 years of dictatorial rule, he instilled fear in Albania through purges and executions.

Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union and Enver Hoxha of Albania (Photo: Llaberia / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED])

However, Albania’s diplomatic relations with communist and socialist states that had supported it gradually deteriorated. After relations between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union worsened, Hoxha severed ties with neighboring Yugoslavia in 1948, despite initially good relations. Relations with the Soviet Union also worsened as Nikita Khrushchev escalated de-Stalinization, and Albania, which continued to espouse Stalinism, cut diplomatic ties in 1961. From 1961 to 1978, Hoxha’s patron was communist China, from which Albania received some about 5 billion US dollars in military and economic aid. After Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, Hoxha, suspicious of China’s burgeoning outreach to the West, began to denounce it. In 1978, China cut off all aid to Albania. After the break with China, Albania became completely isolated.

Hoxha also effectively banned contact with the outside world for citizens. Foreign travel was restricted to official delegations, and private travel abroad was forbidden. Watching Italian television broadcasts—whose signals could reach Albania—was also banned. To defend communist Albania from foreign invasion, Hoxha spent a large share of the country’s GDP building about 750,000 concrete underground shelters (bunkers).

A bunker built on a hilltop (Photo: Dennis Jarvis / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED])

In 1967, Hoxha delivered a speech launching a struggle against religious ideology, brandishing the slogan “religion is the opium of the people” slogan (Note 7). Clergy, with their strong international ties and resistance to communist propaganda, were seen as a threat and rivals. All churches and mosques were shut, and some religious structures of cultural value were destroyed. Nine years later, in 1976, the Party of Labour declared Albania the world’s first atheist state, banned religious belief in the constitution, and imposed penalties for attending religious ceremonies or possessing religious books. In the same year, the country was renamed the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania.

In 1985, Hoxha died of illness, and leadership over state affairs passed to Ramiz Alia of the Party of Labour, Hoxha’s successor and nominal head of state.

Albania after the Collapse of Communism

The 1989 Eastern European revolutions, symbolized by the fall of the Berlin Wall, clearly affected the situation within Albania. In 1990, tens of thousands, mainly young people, poured into the streets of Tirana to demonstrate against the government. After the protest, about 5,000 Albanians crowded into foreign embassies seeking asylum. A 3-day demonstration begun by students at the University of Tirana drew in intellectuals and workers and aimed at transforming the political system. In talks with Alia, the student group demanded political pluralism; Alia yielded, allowing the formation of independent parties other than the Party of Labour. 3 days after recognizing a multiparty system, Albania’s first opposition party, the Democratic Party, was founded. Its main founders were students and university professors, among whom the cardiac surgeon Sali Berisha and Gramoz Pashko—who had just earned a PhD in economics at the University of Tirana—emerged as leaders.

On 1991–3–31, Albania held its first free elections in 60 years held. Turnout was about 99%, with the Party of Labour taking about 56% and the Democratic Party about 39%, according to the results. On 1991–4–29, the country was renamed from the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania and the establishment of the Republic of Albania was declared. Alia was elected President of the Republic of Albania. However, amid economic crisis and strikes, the incumbent government lost support, and in February 1992 the parliament was dissolved early. Consequently, elections were held again on 1992–3–22. Turnout was about 90%, the Democratic Party won 62%, and Berisha was elected president. This Democratic victory was a major step toward liberalization in Albania.

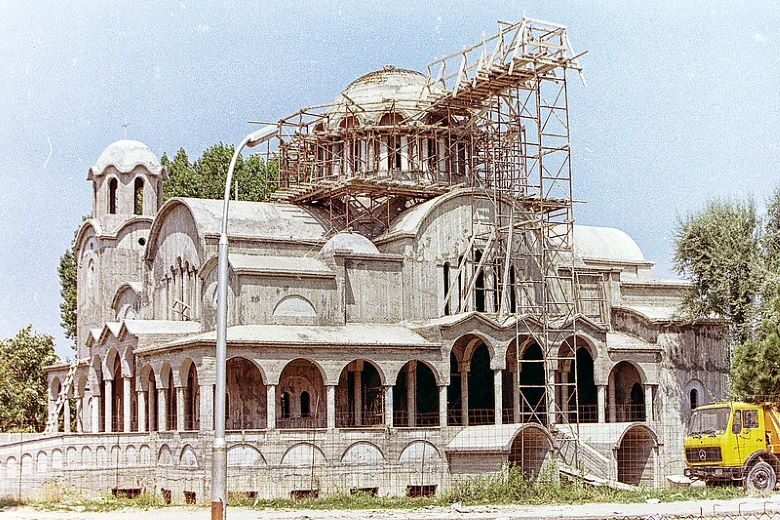

A church being rebuilt in Albania in 1995 (Photo: Pasztilla / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED])

The Republic of Albania that began in 1991 struggled with poverty. Although it transitioned to a free-market economy, most citizens were unfamiliar with market institutions and practices. In this context, pyramid schemes began to spread (Note 8). A pyramid scheme is an illegal financial fraud in which companies reward participants for recruiting new participants, rapidly expanding the chain. The pyramid schemes that ensnared many Albanians began to collapse in 1996. The damage was vast: about 2/3 of the population invested in them, and at its peak, the nominal liabilities of the schemes amounted to almost half of national GDP. Some sold their homes to invest, while farmers sold their livestock to do so. Victims accused the government of having sanctioned and supported the schemes (Note 9), and protests began. In 1997 the protests turned violent, and over the following six months, clashes among the government, gangs, and civilians led to the deaths of more than 2,000 people. In the wake of the turmoil, the ruling Democratic Party lost support, and in 1997 President Berisha resigned.

After this economic crisis, Albania worked with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to introduce strict financial regulations. The Bank of Albania was empowered to prevent unregulated institutions from conducting banking operations. It could be said that the 1997 crisis paved the way for a better economic system in Albania.

Migration Issues

As noted at the outset, since the collapse of the communist system, 40% of Albania’s population has emigrated. Periods when emigration was particularly high include 1991 to 1993, immediately after the borders opened, and around 1997, when the collapse of the pyramid schemes exacerbated poverty and social unrest. Conversely, there was a temporary influx of people in 1999 due to the Kosovo refugee crisis (Note 10). Nevertheless, Albania’s population continues to decline even today.

According to the 2022 Balkan Barometer survey conducted by the Regional Cooperation Council (RCC) (Note 11), 42% of Albanians are considering leaving or working abroad. The main reason is that life in Albania is unaffordable. Albania is said to have a relatively low average monthly wage but a high cost of living. Migration takes many forms: unemployed youth may move out of necessity, or one family member may go first, secure housing with the money earned, and then bring a partner and children. Remittances sent back by those who have moved abroad account for about 10% of Albania’s gross national product (GNP).

In 1991, a mass arrival of Albanians at the port of Bari, Italy (Photo: kosta korçari / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED])

While many people are leaving the country, there are also moves to accept people from abroad. Recently, attention has focused on Italy’s announcement of an agreement to build centers in Albania to receive migrants from Africa and the Middle East attempting to cross the Mediterranean into Italy. The facility is scheduled to open in 2024; it will initially accept 3,000 people, and once fully operational, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni says it should be able to process up to 36,000 people per year stated.

Under this agreement, migrants and refugees rescued at sea by Italian vessels can be temporarily detained in facilities in Albania. Within the European Union (EU), human rights rules allow all arrivals to apply for asylum, so forced returns are not permitted. However, as Albania is not an EU member state, these rules do not apply there, and migrants rescued by Italy and brought into Albania could be forcibly returned. Italy could also circumvent the Dublin Regulation, which requires the first country of arrival to care for migrants and process asylum claims. While Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama expressed willingness to support Italy in managing migration flows, Prime Minister Meloni promised to advocate for Albania’s EU accession.

Crime Issues

Albania has such pervasive organized crime that it has been called a “heaven for illegal trade.” Recently, minors have been targeted by criminal groups, and between 2018 and 2021 the number of minors investigated or arrested on drug-related charges nearly doubled. Such organized crime spread after the collapse of the communist system in the 1990s, and is thought to be caused by the poverty and social turmoil triggered by financial collapse.

Albanian criminal organizations have also influenced politics. A 2014 European Commission report found that the judiciary and elected officials in Albania were highly vulnerable to the influence of criminal organizations. When a law banning people with criminal records from holding office was passed in 2016, it became apparent that one minister, 7% of MPs, and five mayors had criminal histories, including offenses such as drug trafficking and participation in prostitution rings. There have also been allegations that criminal groups bought votes in connection with particular parties during elections. As one example, a recorded conversation captured a suspect arrested for drug trafficking being prompted by someone to contact the mayor to prepare money because voters wanted to sell their votes. Given this reality, some argue that elections in Albania cannot be won without the support of organized crime.

Tirana’s streets immediately after an election (Photo: Lee Phelps Photography / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED])

Among Albanian journalists, there appears to be a perception that reporting on the nexus between politics and crime is dangerous. According to a 2015 report by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), more than half of the 121 Albanian journalists surveyed said they frequently or sometimes avoid stories, with crime and politics the most avoided topics.

Albanian organized crime extends abroad as well. For example, criminal groups with Albanian roots are said to be at the top of the UK cocaine market. However, having Albanian roots does not necessarily mean they are connected to criminal organizations within Albania itself.

Compensation Issues

Furthermore, the government has failed to provide adequate compensation to the families of those executed during the communist era. In 2009, a bill was adopted to provide monetary compensation to those who, based on final judgments and other official decisions during the communist era from 1944 to 1991, were executed, imprisoned, exiled, or placed in psychiatric facilities or under investigation without trial. Compensation is paid in annual installments, up to a maximum of 8 years. The law also provides for payments to families of political prisoners who were executed. However, compensation that should have been completed within 8 years has still not been completed due to delays.

In 2010, the remains of 13 people who had gone missing during the communist era were exhumed on Mount Dajti in Albania. This excavation was a civil initiative, and the government has not been cooperative in the search for the missing (Note 12). While many survivors of communist-era persecution have been recognized and compensated, the families of the missing have not.

Aiming for EU Membership

Many Albanians believe that EU membership will improve living conditions, and Albania applied to join in April 2009. However, the EU had been dragging out Albania’s accession process. 13 years after the application, in July 2022, accession talks with the EU began. According to the EU’s 2022 report on Albania, while some preparations are in place, further efforts and sustained commitment are needed in areas such as freedom of expression, the fight against organized crime, and the fight against corruption. Regarding migration, Albania is expected to align its visa policy with that of the EU.

Prime Minister Edi Rama and the President of the European Parliament (Photo: Martin Schulz / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED])

However, will joining the EU truly lead to a better Albania? Some point out that in the agreement between Italy and Albania to build migrant centers, Italy focuses on using Albania’s non-EU status—which allows forced returns—as a means of deterring migration. Moreover, although fewer Albanians are seeking asylum in EU member states than at the peak, the number rose in 2021. Thus, if Albania joins the EU and freedom of movement is applied, outward migration could increase even further.

In this way, although Albania has overcome a tragic era of dictatorship and seen improvements, it still faces many problems. What changes will Albania experience in the future, and what history will it leave behind?

Note 1: According to the European Albanian Doctors Association, over the past 10 years, more than 3,000 doctors have left Albania, a country of about 2.8 million people. While OECD countries have an average of about 3.6 doctors per 1,000 people, Albania has about 1.93. In response to student protests, current Prime Minister Edi Rama lamented that medical students pay only 1/16 of the real cost borne by the state and that medical students educated at minimal tuition funded by Albanian taxpayers leave the country immediately after graduation .

Note 2: The 1st Balkan War was a war in which the Balkan League—Serbia, Bulgaria, Montenegro, and Greece—declared war on the Ottoman Empire in 1912 and won in 1913. Subsequently, disputes within the Balkan League over the division of territories acquired in the 1st Balkan War led to the 2nd Balkan War from June to August 1913.

Note 3: Representatives of the Ottoman Empire attended the beginning of the London Conference and signed an armistice for the 1st Balkan War. However, after a coup in January 1913, the leader Enver Pasha withdrew the Ottoman Empire from the conference. The Treaty of London was signed on May 30, 1913 in the absence of the Ottoman Empire, and after further discussions, the decision to establish the Principality of Albania was made.

Note 4: Following a movement for independence from Serbia and NATO’s military intervention and occupation in 1999, Kosovo declared independence in 2008, but Serbia does not recognize it and still considers Kosovo a province of its own. Kosovo is also not a UN member state at present.

Note 5: Fascists refers to adherents of the fascism adopted by Italy at the time. Anti-fascist forces were those resisting Italy, which then ruled Albania.

Note 6: Stalinism is “the method of rule, or policies, of Joseph Stalin, leader of the Soviet Communist Party and state from 1929 until his death in 1953,” and is associated with “rule by terror and totalitarian control.”

Note 7: “Religion is the opium of the people” is Karl Marx’s phrase, which likened the role of religion in soothing real suffering to opium, then used as an analgesic.

Note 8: At the time, Albania had few private banks, and the three state-owned banks that held 90% of deposits had mounting nonperforming loans, leading the Bank of Albania to impose credit ceilings on them. As banks could not meet private credit demand, an informal financial market grew. Companies that entered this market were initially seen as ethical and significant economic contributors, but some deposit-taking firms emerged that invested on their own account rather than lending—forming the basis of the pyramid schemes. There were two main factors behind the collapse that began in 1996: first, at the end of 1995, the UN suspended sanctions against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, cutting off a crucial revenue source—arms smuggling—for firms running the schemes; second, in early 1996, major firms running the schemes began to raise interest rates, and multiple investment funds increased rates to win market competition.

Note 9: The government encouraged investment in companies running the pyramid schemes, and some firms made campaign contributions to the then-ruling Democratic Party in the 1996 elections. There were also suspicions that many government officials benefited from these investment plans. The only skeptic was the Governor of the Bank of Albania, who urged an investigation—but was ignored.

Note 10: The Kosovo conflict arose from a dispute between ethnic Albanian forces in Kosovo—then part of Serbia—seeking independence, and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, dominated by Serbia. When NATO began airstrikes against Yugoslavia in 1999, Yugoslavia launched mass expulsions of ethnic Albanians from Kosovo, and many refugees fled to neighboring countries.

Note 11: The Regional Cooperation Council (RCC) is a cooperation framework for the South East Europe region.

Note 12: The government repeatedly cited procedural reasons for not issuing exhumation orders for locations reported as “possible burial sites of the missing.” Critics also argue that the government prefers projects likely to attract tourism revenue—such as “bunk’art” (turning bunkers into art)—over searching for the missing, because it does not want to expose past atrocities.

Writer: Nozomi Kishibuchi

Graphics: Yudai Sekiguchi

前回の記事で海上移民問題が取り上げられていましたが、アルバニアの移民受入センター完成によって改善の可能性があるんですね。今年完成予定とのことで、完成後の動きが気になります。