In February 2023, the Italian authorities detained and fined a rescue ship operated by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) that had been conducting migrant and refugee rescue operations in the Mediterranean. Why did an organization performing rescues end up being policed and penalized?

In the background is the reality that large numbers of migrants and refugees are crossing the Mediterranean toward Europe, including Italy, and European countries are trying to stop them. What measures are EU member states taking to address this influx of migrants and refugees? This article examines the EU’s responses and the problems surrounding them.

Migrants and refugees crossing the Mediterranean (Photo: Brainbitch / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

目次

EU migration and refugee issues

In recent years, Europe has seen a significant influx of migrants and refugees. Over the 8 years from 2014 to 2021, a total of around 2.3 million people entered Europe, and at the peak in 2015, more than 1 million migrants and refugees crossed borders. People head for Europe to flee a variety of hardships at home. Those who move to escape poverty, seek economic opportunities, or remit money to their families are referred to as migrants, economic migrants, or sometimes economic refugees. Those who flee conflict, violence, or persecution are called refugees. People often move for multiple reasons, making neat categorization difficult. Here, we outline where they come from and how they move.

First are refugees from Syria. Following the wave of democratization known as the “Arab Spring” that swept Arab countries in the Middle East and North Africa from 2010 to 2012, many Syrians began fleeing at home and abroad to escape the conflict that erupted in 2011. The peak of displacement came in 2015, when fighting between IS (Islamic State) and various domestic and foreign actors was most intense. Many people from the Middle East and Central Asia—such as Iraq, Afghanistan, and Yemen—also aim for Europe as refugees fleeing conflict.

Many refugees from the Middle East enter Greece via Turkey or enter EU countries through Eastern Europe. Turkey and the EU concluded an agreement in 2016 to prevent migrants and refugees from entering the EU, but in 2020 Turkey reversed course, and tens of thousands of refugees began entering Greece. To curb flows from the Middle East, Eastern European countries took measures such as building barriers, yet they have proactively received refugees from Ukraine since 2022.

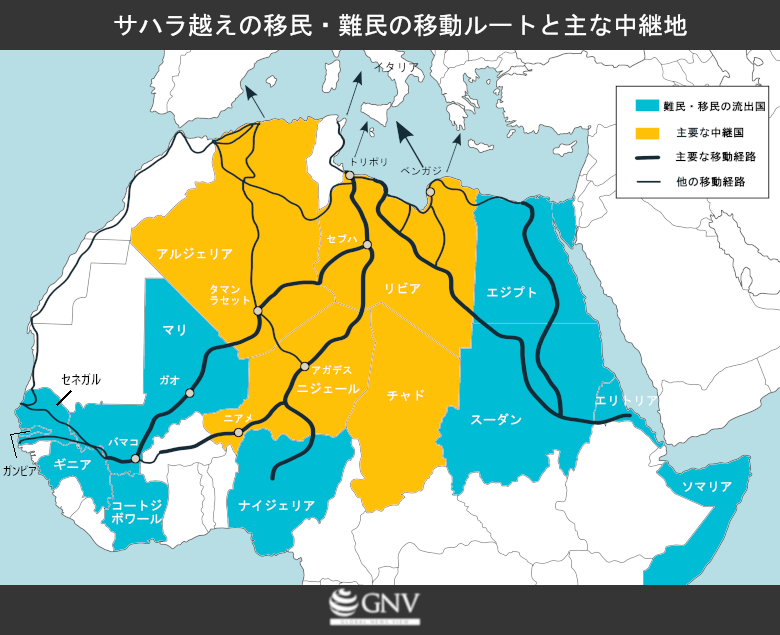

Next, consider migrant and refugee movements within Africa. In West Africa, including Nigeria and Mali, civilians flee as refugees to escape conflict. Movements are also seen from East Africa, including the Horn of Africa. In Eritrea, people flee conscription and government repression, while in Somalia citizens seek safety from conflict at home and abroad. In addition, many people move from numerous African countries as economic migrants to escape economic crises and poverty.

Most migrants and refugees originating in Africa remain in neighboring countries waiting until they can return home, but some continue onward to Europe. This requires crossing the Sahara Desert, a notoriously grueling route (see here for details). Among West African migrants and refugees, some aim for Europe via Morocco and Western Sahara, which is occupied by Morocco. Because they seek to transit the Spanish enclaves in North Africa that border Morocco, Morocco effectively controls their movement in and out. When relations with European countries such as Spain are good, Morocco strictly polices the border, but when relations deteriorate it loosens control and allows crossings. This can lead to large numbers of migrants and refugees entering Europe. Many migrants and refugees from East Africa are said to pass through Sudan and converge in Libya.

Many who gather in Libya attempt to cross the Mediterranean to nearby European countries such as Italy. The route across the Mediterranean from Africa to Europe is perilous, and many people go missing at sea; it is estimated that over the 8 years from 2014 to 2021, about 25,000 people died or went missing. Even so, many continue to head for Europe, and in 2022 more than 100,000 people are said to have crossed the Mediterranean.

Why do migrants and refugees heading from African countries to Europe concentrate in Libya? Libya was once one of the main destinations for migrants and refugees within Africa, as it was relatively better off economically. However, amid the Arab Spring, after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi’s long-standing dictatorship in 2011, the country has remained unstable with conflicts breaking out across regions. Because the central government does not function sufficiently, control over migrants and the coast guard has been fragmented among militias and others. These governance gaps make it possible to exploit loopholes, increasing the opportunities for migrants and refugees to cross borders and reach Europe.

Fence installed between Morocco and the Spanish enclaves (Photo: fronterasur / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Yet the lack of effective national territorial control also brings dangers. Many migrants and refugees are arrested soon after arriving in Libya by militias or armed groups, kidnapped, and then detained in migrant detention facilities. Because crossings are dangerous, there are also smugglers who charge high fees to put people on boats to Europe. To maximize profits, they often cram people onto small, aging vessels, resulting in many transport boats capsizing in the Mediterranean.

EU maritime measures and cooperation with Libya

We now trace the EU’s measures to deal with migrants and refugees arriving across the Mediterranean from Africa.

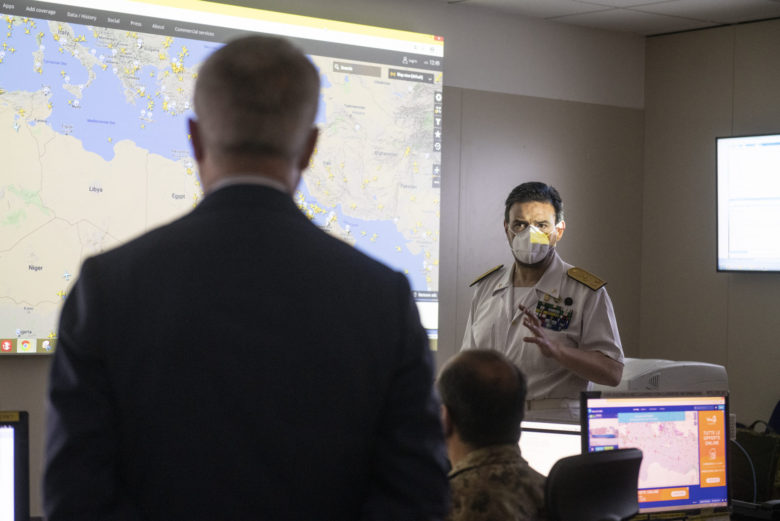

To combat human trafficking and smuggling, military operations have been conducted in the Mediterranean. In May 2015, the EU decided to establish the EU naval force in the Mediterranean (EUNAVFOR MED), and in June launched the first phase, monitoring smuggling and trafficking and assessing the situation. In October, the second phase of EUNAVFOR MED—Operation Sophia—began. Operation Sophia enabled operational measures, including boarding and inspections of suspicious vessels and their seizure.

In 2020, EUNAVFOR MED moved into a new phase with Operation Irini, which began patrolling the Mediterranean. Surveillance data are reportedly shared with the United Nations and with Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex).

Inside EUNAVFOR MED headquarters (Photo: Ministero Difesa / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Search and rescue (SAR) and returns of migrant and refugee boats have been conducted mainly through cooperation with Libya. Since 2016, the EU has begun training Libya’s coast guard, aiming to strengthen maritime SAR capacity and establish a system to push back migrants and refugees to Africa. In February 2017, the EU decided to step up cooperation with Libya. The aim was to further bolster the Libyan coast guard through financial and technical support and to ensure reception capacity for migrants. By 2022, the EU, through its Trust Fund for Africa, had provided €455 million in support to Libya, most of it for migration and border management. Frontex also supports the coast guard’s searches by providing flight surveillance information to Libya, which the coast guard reportedly uses to detect and seize migrant and refugee boats.

These policies have drawn criticism that the EU has offloaded responsibility for surveillance in the Mediterranean onto Libya and abdicated its own duties to monitor and rescue. It also appears that preventing arrivals in Europe is being prioritized over saving lives.

Human rights abuses in Libya

What happens to migrants and refugees intercepted at sea and returned to Libya? Numerous human rights abuses against migrants and refugees in Libya have been reported. With EU support, the Libyan coast guard captured and forcibly returned about 80,000 migrants and refugees in the Mediterranean over the five years from 2017 to 2021. Many of those returned were robbed of their belongings and assets by the coast guard and then detained in facilities run by Libya’s Department for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM) or in detention centers run by militias.

According to a report published in 2021 by the international human rights NGO Amnesty International, many detained migrants and refugees are forced to pay large ransoms to be released or are subjected to forced labor. Inside detention facilities, there have been reports of torture, sexual violence, and other abuses. Seeking financial support from the EU while showing little interest in improving treatment, some DCIM facilities have reportedly withheld adequate food or even shot detainees.

In September 2022, the International Criminal Court (ICC) assessed that such abuses against migrants and refugees in Libya may amount to crimes against humanity and war crimes. Nonetheless, while acknowledging evidence of these human rights violations, the EU has maintained support for policies that facilitate forced returns to Libya. Human Rights Watch has condemned this, saying that supporting the Libyan coast guard despite knowledge of these abuses means Italy and other EU states are complicit in such crimes.

Activities of the Libyan coast guard (Photo: Brainbitch / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Divergence of measures within the EU

So far we have looked at the EU’s overall approach, but measures can diverge among member states. Countries that serve as arrival points, such as Italy and Greece, have strongly called for burden-sharing within the EU.

Meanwhile, even maritime rescue efforts have seen governments falling out of step. Because the EU’s rescue operations are insufficient, some NGOs conduct rescue activities in the Mediterranean, but certain governments have sought to obstruct these humanitarian efforts. They argue that operations by civilian rescue ships facilitate entry into the EU and encourage crossings. Italy, seeking to limit arrivals and its own burden, has taken a hard line against rescue ships, including the arrest of a German captain of a civilian rescue vessel in 2019. Greece has also taken a tough stance; rescue workers from an NGO that conducted operations off Greece were arrested in 2018, and a trial began in 2023.

Strengthening EU border control

Next, we look at the EU’s border management policies. Centered on EU countries, the Schengen Area—where internal border controls are lifted—has been formed by agreement. As a result, entry control at the external borders of the Schengen Area is crucial. Border management in the EU has primarily been carried out by two agencies: Frontex, which performs border surveillance and control, and the European Agency for the Operational Management of Large-Scale IT Systems in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (eu-LISA), which manages information systems.

Established in 2004, Frontex has monitored and guarded the EU’s borders. In October 2016, its powers were expanded and strengthened, making it possible for the agency to conduct its own border management activities and to purchase and deploy its own equipment, enabling faster operations. In 2021 it contracted with private companies to begin aerial surveillance using unmanned drones.

People protesting Frontex and declaring “Refugees welcome” (Photo: Rasande Tyskar / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

By contrast, eu-LISA began operations in 2012 for migration and border management, and its mandate was reinforced in 2018. eu-LISA develops and manages information systems relevant to migration and border control and provides them to competent authorities in member states, which use the data to verify identities and conduct criminal investigations. Specifically, the EU introduced the European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS) in 2016 to streamline border management, requiring travelers to submit information as a condition of entry to Europe. It has also deployed the Schengen Information System (SIS), into which authorities input data during border checks. eu-LISA develops and operates these systems, managing people entering the Schengen Area from outside. The EU has also considered introducing biometric registration for non-EU nationals entering from 2023, moving toward more extensive personal data collection.

However, a one-size-fits-all approach of detecting movements with technology and forcibly returning people cannot be considered migrant- and refugee-centered. In principle, states have an obligation to conduct individual interviews and determine whether to grant refugee protection to people fleeing conflict and human rights abuses. Yet the EU’s border management policies appear to prioritize using technology to keep people away from the EU’s borders over strengthening systems that assess protection needs.

The EU has also explored proposals to establish facilities in multiple African countries, including Libya, to conduct asylum processing. It argues the aim is to determine before travel whether protection in Europe is needed, thus reducing the incentive to attempt the dangerous sea crossing. This idea—effectively moving the EU’s border into Africa—has drawn criticism from African countries and the United Nations.

The border industrial complex

As the EU has implemented measures targeting migrants and refugees, the powers and budgets of agencies responsible for border control have expanded. Neither Frontex nor eu-LISA carries out border management entirely on its own; particularly on the technology side, they commission private companies. As a result, some private firms have become beneficiaries of increased spending by EU bodies. Between 2014 and 2020, Frontex spent €434 million and eu-LISA spent €1.5 billion on contracts with private companies.

Many of Frontex’s largest contracts relate to aerial surveillance; it spent over €100 million for this between 2014 and 2020. To monitor boats carrying migrants and refugees in the Mediterranean using unmanned drones, it signed large contracts, paying €50 million each to Airbus, a European aerospace and defense conglomerate, and Elbit Systems, an Israeli arms company. This spending on aerial surveillance can be seen as an investment in providing information to the Libyan coast guard to return migrants and refugees to Libya.

Satellite image of the Mediterranean coast (Photo: NASA Johnson / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

eu-LISA’s largest contracts have been tied to new biometric matching systems. To add biometric registration to the entry/exit system, eu-LISA spent €300 million with private companies. Because there are fewer but larger contracts for the IT systems in which eu-LISA is involved, there are concerns about oligopolies by major tech firms, as noted. Oligopoly also means that updates and expansions of databases tend to lead to further contracts with the original developers, funneling multiple contracts and large sums to a handful of companies.

Through the activities of Frontex and eu-LISA, there is also concern that EU borders are becoming “datafied.” The EU seeks to manage borders as data, but relies on private companies for the technology. As cooperation between EU bodies and private firms deepens, some describe the emergence of a border industrial complex—in other words, EU agencies’ increasing outlays on migration control create lucrative opportunities for companies in the defense, security, and technology sectors that provide these systems.

What about addressing the root causes?

We have looked at the EU’s measures to address the inflow of migrants and refugees, but what about tackling the root causes? People attempt to reach Europe to escape conflict, repression, and extreme poverty. Unless these problems are resolved, many will continue trying to reach Europe.

EU countries have been providing a certain level of support to Africa on an ongoing basis, and—in response to rising migration—have initiated assistance targeted at this issue. At the Valletta Summit in 2015 between the EU and African countries, the parties jointly announced an Action Plan to address migration and refugee issues. It outlined five points: tackling the root causes of displacement, promoting legal migration, strengthening protection for migrants and refugees, combating human trafficking, and cooperation on return and reintegration. Following the summit, the EU established an Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, aiming to improve instability in African countries so that migrants and refugees would not feel compelled to undertake dangerous journeys to Europe.

However, such support cannot stop the armed conflicts that generate refugees. Nor can “aid” alone resolve poverty in Africa and the vast economic disparities with Europe. Behind these inequalities lie structural issues in the global economy—such as unfair trade, illicit financial flows, and debt problems (see here for details). Addressing the problem requires not just support for Africa, but the establishment of fairer trade rules.

Moreover, the EU measures discussed in this article all emphasize stemming the flow of migrants and refugees into the EU and returning them to Africa, rather than aiming for fundamental solutions. We hope the EU will focus more on addressing root causes and that this issue will be resolved in the future.

Writer: Haruka Gonno

Graphic: Hinako Hosokawa

0 Comments