The vast majority of the world, consisting mainly of low-income countries, is collectively referred to as the “Global South.” This is a concept that has been widely used around the world for decades. It had rarely appeared in Japanese media, but starting in January 2023 the situation changed dramatically: outlets began using this expression in their coverage, and references to the “Global South” surged. The volume of articles grew to the point that pieces explaining the concept of the Global South, such as this explanatory article, became necessary, and one could say the concept has achieved a certain degree of foothold in Japan’s public discourse.

Since January 2023, it’s not as if the circumstances of the countries and peoples of the Global South suddenly changed. So why did Japanese media dramatically increase their use of this catch-all label for these countries? This article explores the reasons behind this phenomenon.

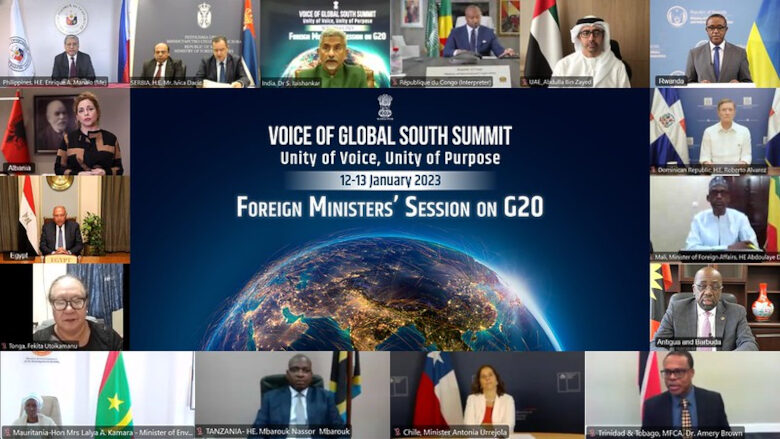

Scene from India’s “Voice of the Global South Summit 2023” (Photo: MEAphotogallery / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

What is the Global South?

From the end of World War II through the 1960s, many independent countries emerged as they broke free from the control of high-income countries. Because of long years of colonial rule and the unfair global economic system that has continued to disadvantage them even after independence, these countries tend to have high poverty rates and a lack of infrastructure necessary for development.

In this context, several labels emerged to group these countries together. For example, based on Cold War political and economic thinking, countries were labeled as the capitalist “First World,” the socialist/communist “Second World,” and the “Third World” of non-aligned countries—labels that categorized the globe. However, the label “Third World” often came to be perceived negatively and, with the end of the Cold War, it fell out of use. Labels based on degree of development—such as “developing countries” or simply “developing” or “low- and middle-income countries”—also came into use. Yet the label “developing country” lends itself to a favorable interpretation for high-income countries: that these so-called developing countries are advancing toward the level of “advanced” countries—a reading that can be seen as a kind of “hope.” Even countries that stagnate or regress in terms of economy or development continue to be called “developing.”

Against this backdrop, the label “Global South” rose to prominence. First used in 1969, its use increased especially after the Cold War. Its etymology lies in the fact that many low-income countries are concentrated in the Southern Hemisphere. Corresponding to the “Global South,” there is also the “Global North,” composed of high-income countries. However, the geographical connotation is not particularly strong, since some Global North countries are in the Southern Hemisphere (such as Australia and New Zealand), while some Global South countries (such as those in South Asia) are in the Northern Hemisphere.

Rather than the geographic aspect, “Global South” emphasizes the relationship with the Global North in terms of history, politics, and economics. In other words, it reflects a recognition of countries that share a history of being colonies and the current reality of continued exploitation of their resources and labor by high-income countries, as well as political and economic marginalization. It also has a movement-like dimension in which these countries seek solidarity to escape such disadvantageous conditions. Some experts even point out that the Global North and Global South can exist within a single country. In other words, even within countries considered high-income there are marginalized regions and communities with high poverty rates, while in some countries considered low-income there are regions and communities where wealth and power are concentrated.

Sorting coffee beans, Ethiopia (Photo: Niels Van Iperen / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

The rise of the “Global South” in Europe and the United States

Since the 2010s, the label “Global South” began appearing somewhat more often in the reporting of high-income media in Europe and the United States (Note 1). There was no single triggering event; rather, it came to be used broadly across diverse topics such as migration and refugees, world population, climate change, international trade, and issues within the Catholic Church. The number of citations in academic papers also surged around the same time.

Attention to the Global South among Western media intensified further in 2021. In the wake of the global spread of COVID-19 from 2020 onward, phenomena such as high-income countries and their pharmaceutical companies leaving low-income countries behind, and low-income countries pushing back against high-income countries that failed to take or even impeded serious measures as the climate crisis worsened, formed part of the backdrop. In fact, in 2021 and 2022, “Global South” appeared most frequently in Western media in November, when the UN Climate Change Conferences (COP) were held (Note 2).

In 2022, attention to the Global South increased further with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine beginning on February 24. From the outset, countries supporting Ukraine—including those in the West—sought public support for anti-Russia sanctions and aid to Ukraine from around the world. However, many countries in the Global South took a neutral stance (Note 3). Within days of the invasion this state of affairs had become clear, and when a UN General Assembly resolution condemning Russia was adopted on March 2, numerous abstentions—notably among African countries—were criticized by Western countries.

Toward these Global South countries, the United States requested cooperation and also applied pressure. In response to such attitudes, in August 2022 the South African government said it “smacks of patronizing bullying.” There were even instances of U.S. interference in domestic politics, such as applying pressure on March 7, 2022 to pass a no-confidence vote to oust Pakistan’s then Prime Minister Imran Khan, who sought to maintain neutrality on the Russia-Ukraine war. From mid-2022 onward, in order to strengthen sanctions on Russia and support for Ukraine, leaders of countries such as Canada and the United Kingdom began making statements that showed consideration for the Global South and pledged increased support.

Major media in countries such as the United States, France, and the United Kingdom widely covered Western efforts to win support from low-income countries and the challenges involved, and the frequency with which they used the term “Global South” rose accordingly.

Discussion of “loss and damage” at COP26 (Photo: COP26 / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Japan’s government follows the West

Compared to other Western countries, the Japanese government lagged far behind in when it began using the expression “Global South.” According to the Prime Minister’s Office website, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida first used the expression in a speech at the Reiwa Rincho (a policy forum) held on October 27, 2022 (Note 4). Kishida mentioned the “Global South” again in November (twice) and December (once), but in January 2023 the number of references in speeches, press conferences, and media contributions jumped to six. Mentions continued thereafter and peaked at eight in May.

The trigger for the Japanese government’s frequent use of the term “Global South” was the G7 summit held in Hiroshima in May 2023. This is also why Kishida’s usage was most frequent that month. But why did the Japanese government seek to link the Global South to the G7 summit, an event comprising only seven Global North countries? As the G7 chair, the Japanese government claimed it would “listen” to the Global South and that, on “global issues,” it wanted to make the G7 summit an opportunity to consider “how to work with the Global South,” it said. The major underlying reason is thought to be the Russia-Ukraine war, which the G7 had identified as a “priority issue.”

This intent can be gleaned from Kishida’s speeches. For example, in the first speech where he mentioned the Global South, he already referred to “strengthening relations” with the Global South in the context of the G7 and the Russia-Ukraine war. In his New Year’s press conference in January 2023, in response to a question he said, “We will once again firmly confirm sanctions against Russia and support for Ukraine, and with countries referred to as the Global South,” we will work in “partnership,” and “I would like the G7 to spread that message to the world.” As a result, from his first mention in 2022 through July 2023, out of a total of 36 communications in which the prime minister referred to the “Global South,” 33 also mentioned Russia or Ukraine.

The 2023 G7 Hiroshima Summit (Photo: Number 10 / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Media led by the Japanese government

To repeat, the expression “Global South” was coined in 1969 and, in places like the West, has been used frequently since the end of the Cold War, yet it had hardly appeared in Japanese media. Over the decades up to 2023, it appeared in only six Asahi Shimbun articles, five in Mainichi Shimbun, and five in Yomiuri Shimbun (Note 5). Expressions such as “developing countries,” “developing,” and “emerging economies” were mainstream for referring to these countries. However, starting in January 2023, the expression “Global South” suddenly increased in these newspapers. In the seven months from January to July 2023, Asahi Shimbun referred to the “Global South” in 123 articles, Mainichi Shimbun in 123, and Yomiuri Shimbun in 239.

What explains the prevalence of the “Global South” in Japanese reporting? As noted at the outset, there was no major change in the Global South countries themselves. Nor is it likely that Western governments or media influenced Japanese media. As mentioned earlier, Western governments and media had already increased their focus on the Global South from the first half of 2022, while the sudden uptick in Japan came only after January 2023—so the timing does not match. It’s true that on December 21, 2022, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy held a press conference at the White House and delivered a speech to the U.S. Congress, in both of which he mentioned the “Global South.” One could hypothesize that his remarks drew Japanese media attention. However, although Japanese media covered the press conference and speech, in reporting by Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri, the expression “Global South” did not appear.

In January 2023, when Japanese media began referring to the “Global South,” a major event centered on Global South countries took place. On January 12 and 13, India hosted online the “Voice of Global South Summit 2023,” inviting 120 countries. The summit aimed to collect the voices of countries facing the issues confronting the Global South and to strengthen solidarity among them. However, this event did not trigger Japanese media attention to the Global South. Yomiuri Shimbun covered the event in two articles, but Asahi and Mainichi didn’t even mention its existence.

On the subject of the “Global South,” it seems Japanese media are trying to listen not to the voices of Global South countries and peoples, but to the voice of Japan’s prime minister. As Kishida’s references to the “Global South” surged in January 2023, references in reporting also increased in the same month. And in terms of coverage, outlets simply quoted Kishida’s words directly, without original reporting or analysis. For example, of the five Asahi Shimbun articles in January that mentioned the “Global South,” four reported that Kishida had mentioned it. In Mainichi Shimbun, all three articles in January that mentioned the Global South centered on Kishida’s remarks. Yomiuri Shimbun mentioned the Global South in 19 articles that same January—more than the other two—but in eight of those, the trigger was remarks by the prime minister or foreign minister. Of the 19, only four focused on Global South countries themselves.

From January 2023 onward, Japanese media continued, as if repeating the Japanese government’s view, to increase occurrences of “Global South” leading up to the G7 Hiroshima Summit. In May, when the summit was held, coverage related to the Global South spiked at all papers and reached a maximum.

Media that do not listen to the Global South

Looking at coverage in each paper, “Global South” most often appeared in the context of the Russia-Ukraine war. For example, in Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri between January and July 2023, roughly 80% of the articles that mentioned the “Global South” also included “Ukraine” (Note 6). In editorials during the same period at all three papers, “Ukraine” also appeared in pieces that mentioned the “Global South.” Note that editorials express a newspaper’s official position.

In their editorials, all three outlets advanced arguments similar to the Japanese government’s. At the G7 Hiroshima Summit held from May 19 to 21, they argued for the need to coordinate and cooperate with Global South countries on the Russia-Ukraine war. At the close of the summit, Yomiuri Shimbun’s editorial (May 22) asserted that “to force Russia to withdraw,” it is “essential to secure broad coordination” with the Global South. Asahi Shimbun’s editorial (May 22) noted that the G7 needs to “listen sincerely to the voices” of Global South countries and “demonstrate a willingness to tackle common issues beyond its own interests.” Mainichi Shimbun’s editorial (May 23) said the summit “must be a starting point toward coordination between the G7 and the Global South.”

Some editorials also praised the dialogue with the Global South at the summit. Asahi Shimbun’s editorial (May 22) said that “the results are still unclear,” but that the summit “placed emphasis on building relations with the Global South. Leaders of diverse countries were invited, and nearly half the summit was devoted to discussions including them.” Mainichi Shimbun’s editorial (May 23) stated, “As global divisions deepen with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it was timely to set the stage for dialogue. The G7 leaders’ declaration reflected strong consideration for the Global South.”

However, there are several major problems with these editorial stances. First, given its nature, the G7 is not a venue that enables sincere engagement with Global South countries or efforts at coordination. The G7 is a gathering of seven Western economic powers; Global South countries are not members from the outset. They also cannot participate in setting the G7 agenda or drafting its declarations. Six countries from the Global South were invited as guests to the Hiroshima summit, including those representing the African Union (AU) and the G20. However, the G7 countries are at the center, and those six countries, not on equal footing with the G7, cannot necessarily represent the 120-plus countries that hold diverse views and positions.

Prime Minister Kishida of Japan at a press conference (Photo: Prime Minister’s Office of Japan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0])

Moreover, while both the Japanese government and media have increased references to the Global South and claim it is necessary to listen to Global South voices, as noted earlier the main subjects, perspectives, and bulk of content have concerned Japan, Western countries, Ukraine, or Russia—not the Global South itself. The aim of collaborating or coordinating with the Global South remains to strengthen cohesion against Russia and support for Ukraine; the problems and priorities of the Global South receive little attention.

Attention to Global South countries has been extremely low to begin with. In Japanese media, coverage related to Africa and to Latin America each accounts for only about 2–3% of international reporting, and those shares have declined since the Russia-Ukraine war. Even coverage of Southeast Asia and India, relatively close to Japan, accounts for a small share of overall coverage, indicating that geographic distance does not necessarily influence volume. GNV’s research has also shown that the higher a country’s poverty rate, the less likely it is to be covered. In an information environment where it is difficult for audiences of the Japanese government and media even to encounter information that could prompt understanding of the Global South’s circumstances, how can Japan achieve genuine collaboration or coordination with the Global South?

Issues of the Global South that go unreported

In Japan’s Global South-related reporting framed by the Russia-Ukraine war, coverage sometimes addresses why Global South countries are not cooperative. For example, some articles mention colonial history, backlash against approaches that “force them to pick a side” in conflicts, or economic ties with Russia. Not a few reports also assert that Global South countries are being swayed by Russian propaganda.

However, the reasons why many Global South countries do not respond to cooperation requests from Western countries such as the G7 are not so simple, and there is far too little reporting that delves into the background. Many Global South countries view Russia’s invasion of Ukraine critically as a violation of international law; but regardless of responsibility, the continuation of the war itself and the sanctions imposed by Western countries are causing great damage to Global South countries. One editorial argues that “if actions trampling international law like Russia’s aggression are tolerated, order will collapse and their own security will be threatened” (Yomiuri). Yet military actions and violations of international law by Western countries, starting with the United States, have also occurred repeatedly, and in the Global South there is a strong perception that “order” is something arbitrary and led by Western countries. There is hardly any reporting in Japan that critically examines Western actions.

Ecuador’s banana industry affected by the Russia-Ukraine war (Photo: Port of San Diego / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Regarding claims that Russian propaganda is influencing the Global South, there is a tendency to emphasize the threat while lacking accurate evidence about the extent and efficacy of Russian propaganda and influence operations. Meanwhile, the United States and France also conduct propaganda and influence operations. Yet Japanese media single out Russia’s activities as problematic and avoid mentioning those of Western countries.

Even prior to the Russia-Ukraine war, high-income countries neglected the problems faced by the Global South. The current Global South view of the West has been shaped in part by recognition that high-income countries created or exacerbated the Global South’s problems. Exploitation by high-income countries continues to this day through a global economic system that favors G7 countries, even after colonial rule ended, yet this fact goes unreported.

Moreover, aside from the Russia-Ukraine war, many armed conflicts are unfolding in numerous Global South countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, prompting backlash against being pressed by Western countries to respond only to the Russia-Ukraine war. The Yemen conflict, called the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, is something the United States actively helped fuel, and the Global South understands this. Yet in Japan, the Yemen conflict is hardly covered. Japan accepts very few refugees from Global South countries, but in the case of refugees from Ukraine it has actively accepted them and provided generous support.

On climate change, Global South countries have been pressing high-income countries for active measures and have demanded the establishment of a “loss and damage” fund as compensation for harms caused by high-income countries, but high-income countries have shown reluctance. At the 2022 COP, for example, the Japanese government opposed the creation of such a fund and is seen as passive on climate action. In concrete terms, during the 2022 floods in Pakistan—said to have been exacerbated by climate change—one-third of the country was affected, yet Japan’s emergency assistance through the UN was only one-twentieth of its assistance to Ukraine that same year. In addition, during the drought that caused massive damage across East Africa from 2022 to 2023, a UN donor conference sought significant support, but the Japanese government neither attended nor pledged funds. Notably, this donor conference was held on May 24, 2023, just a few days after the G7—at which Japan declared it would stand with the Global South—had closed. Japanese media did not report on this donor conference.

Pakistan during the 2022 floods (Photo: Ali Hyder Junejo / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Challenges ahead for the media

As we have seen, since January 2023 the Japanese government has suddenly started to use the expression “Global South” frequently and has continued to show a desire to strengthen relations with Global South countries. In the background are the G7 Hiroshima Summit, at which Japan held the chair, and designs to strengthen cohesion—including by involving the Global South—in response to the Russia-Ukraine war. However, such actions risk being seen by the Global South as performative—Western countries, including Japan, appearing to stand with them only when low-income countries’ cooperation is needed—and thus it will not be easy to achieve the results being proclaimed.

Why, then, have Japanese media failed to see this, continuing to report using the expressions and framing instilled by their own government? And why, while claiming it is necessary to listen to Global South countries, do they continue to neglect them in their own reporting? Without coverage that fosters understanding of the Global South, coordination and cooperation will not emerge.

GNV has previously pointed out in international reporting the tendency of Japanese media to side with powerful countries and domestic elites and to avoid independently raising issues concerning concentrations of wealth and power. This study again revealed that tendency. Is Japan’s international reporting fine as it is?

Note 1: For example, in the New York Times, the term appeared in roughly ten articles per year between 2013 and 2020 (based on a search of ProQuest’s “New York Times” database).

Note 2: We surveyed the number of articles in major Western English-language media using ProQuest databases.

Note 3: In several UN resolutions condemning Russia, many countries abstained or did not vote.

Note 4: However, about two weeks earlier, on October 14, 2022, he also referred to it in an interview with NHK.

Note 5: For Asahi, data were taken from “Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search”; for Mainichi, from “Mainichi Shimbun Maisaku”; and for Yomiuri, from “Yomiuri Shimbun Yomidas Rekishikan.” The keywords included “グローバルサウス” and “グローバル・サウス.”

Note 6: Asahi Shimbun: 80%; Mainichi Shimbun: 83%; Yomiuri Shimbun: 76%.

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

Graphics: Virgil Hawkins

日本の国際報道はこのままでは良くないと考えているが、改善も望めないのが今の大手メディアの現状であるかと思います。「グローバル・サウス」といった言葉についてもその背景についてももっと掘り下げて報道すべきかと。日本政府のグローバル・サウスに対する姿勢についても問い直す・今抱えている世界的な問題などについても取り上げるべきでした。先んじて情報を取る、深堀するのではなく政権の動向に左右される・政府広報にだけ甘んじているようでは大手メディアの未来はないでしょう。

しっかり最後まで読みました。私はまず発展途上国という言葉から考えていく必要があると感じました。そして、こんなにもグローバルサウスについて考えたことはこれまでなかったので、今起きている様々な問題点に関連づけてもっと理解を深めたいと思いました!☺