Over the three days from May 19–21, 2023, the G7 (Group of 7) summit (leaders’ meeting of major countries) will be held in Hiroshima, Japan. The G7 is an annual international conference where the leaders of the 7 countries—United States, United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, Germany, Japan, and France—and the European Union (EU) gather, and it sets as its purpose to discuss “important issues in the international community of the time, including the world economy, regional situations, and various global issues.” With the 2023 G7 summit being held in Japan, attention to it within the country is growing.

However, around the world there are various doubts raised about the G7, including the claim that rather than aiming to solve problems facing the entire world, it is a gathering to pursue the participating countries’ own interests and to maintain their own power and influence.

Including such doubts, how much is the actual nature of the G7 being reported in Japan? In this article, we look at the existence of the G7 and the problems it faces, and we explore and examine how the G7 is reported.

Scene from the G7 foreign ministers’ meeting held in Karuizawa, Nagano Prefecture, Japan, from April 16 to 18, 2023 (UK Government / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

目次

History of the G7

How did the G7 come into being in the first place? The trigger goes back to the 1970s. In that decade, events such as the 1973 oil crisis had major impacts around the world. In that context, voices grew among Western countries that a forum was needed at the leaders’ level to coordinate policies on the economy, politics, and energy in order to address the problems they faced themselves. For that reason, in 1975, at the proposal of then French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, the leaders of six countries—the United States, United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, Japan, and France—gathered at the Château de Rambouillet in France for the first summit (G6). They discussed the oil crisis, financial crises, and how to emerge from recession. At the same time, the importance of meeting annually to discuss policies to deal with future economic issues was reaffirmed, and since then the presidency has rotated among the member countries.

From the second summit in 1976, Canada joined and the grouping came to be called the G7. After the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, meetings with Russia began to be held outside the summit framework in 1991, and Russia gradually began to participate in G7 meetings as well. By 1997, Russia was attending the full schedule. From the following year, 1998, until 2014, annual meetings of the eight countries including Russia were held, and the group was called the G8. However, in 2014, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine’s Crimea Peninsula, an emergency G7 was held by the other 7 countries, where a decision was made to suspend Russia’s participation in the G8, and since then meetings have once again been held as the G7 of the seven countries excluding Russia.

Volume of G7 coverage

Now let’s look at how the G7 is reported, based on actual data. First, consider the trend in volume of coverage. This shows, year by year, the number of Asahi Shimbun articles between 1993 and 2022 whose headlines included “G7 (G8)” or “summit of major countries (summit of advanced countries).” The place name next to each year denotes that year’s summit host. From this graph, three features of the coverage stand out.

First, the volume of coverage increases significantly in years when the summit is hosted in Japan. Looking more closely, when Japan hosts, reporting focuses heavily on the venue and its preparations. Because a Japan-based summit is a domestic event that draws relatively high domestic interest and allows for longer-term coverage, the volume of reporting tends to be higher.

The second feature is a decline in coverage of the G7 since the start of the 21st century. In the 1990s, coverage was around 100 articles each year, but after 2000 it clearly decreased to an annual average of about 50. Even in Japan-hosted years, more than 300 articles in 1993 and 2000 fell to 243 in 2008 and 121 in 2016, a major drop. Behind this lies the broader trend that the volume of newspaper reporting in Japan—especially international reporting—has declined since the 21st century.

Although the number of articles fell to 30 in 2020, it ticked back up to just under 100 in each of the next two years, 2021 and 2022. This can be attributed to the global spread of COVID-19 focusing attention on how each G7 country responded, as well as the summit convening again after a two-year gap. In 2022, an emergency G7 meeting was also held separately from the main summit, resulting in two gatherings that year (※1), which drew attention and likely increased coverage over these two years.

Third, when the host is a country other than Japan, there is not much variation in the volume of G7 coverage. In other words, even if major developments occur at the G7, that is not reflected in changes in the amount of reporting. For example, in 2014, when Russia’s annexation of Crimea led to the suspension of its participation in the G8, coverage of the G7 (G8) did not increase and remained low, in line with the overall 21st-century trend (※2).

Content of G7 coverage

Next, what exactly does Japanese reporting on the G7 cover? The chart below and the next one classify G7-related coverage over the three years 2017–2019 (※3) by country at the center of the story and by theme. Roughly half of all items reported on the G7 meetings themselves without focusing on any specific country. Among country-specific articles, Japan and the United States accounted for half, with the remaining countries making up the other half. While Japan and the U.S. were covered about 15 times each, Germany, Italy, and other G7 countries had 5 or fewer articles each, indicating a relative concentration on Japan and the U.S.

Next, by theme, politics and the economy each had just under 30 items and were the most common, followed by the military at 9 and the environment at 4. For example, in this period there was extensive coverage of the United States’ isolation at the G7 due to then-President Donald Trump’s protectionism. As the U.S. put national protection first in trade and commerce and refused to cooperate with other G7 countries, discussions stalled and the G7 effectively became dysfunctional. This U.S. isolation likely contributed to politics and the economy being the most frequent themes. On military issues, many articles concerned North Korean exercises and Syria.

Thus, looking at G7 coverage from multiple angles shows that the amount of reporting varies by host location, by country, and by content.

What kind of gathering is it?

Now let’s consider problems with the G7 itself. First is the issue of the criteria for and representativeness of G7 membership. As noted, the G7 began in 1975 as a gathering of economically powerful Western countries to discuss global issues multilaterally. In the past, the G7 countries together accounted for up to 70% of global GDP. However, since the start of the 21st century, that share has dropped, and as of 2021 it had fallen to 30%.

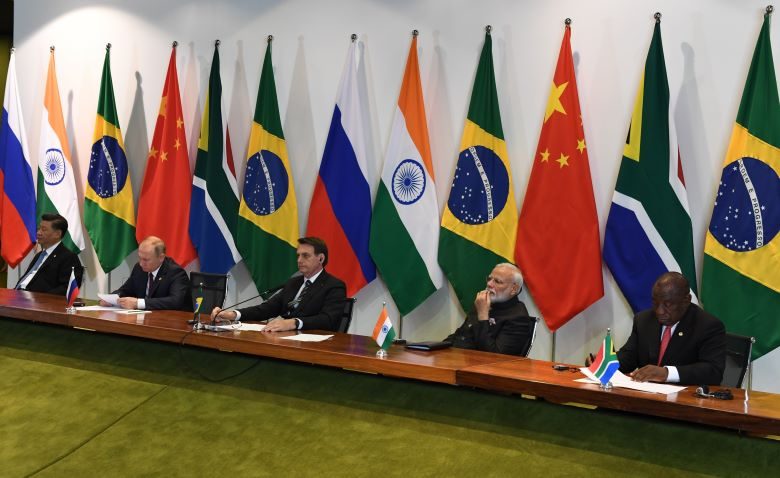

Meanwhile, the GDP of the BRICS—the five rapidly growing economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—has expanded and their share of global output has risen, with some data indicating that by 2023 they accounted for a larger share than the G7. Looking at national GDP rankings, for example, China overtook Japan in 2010 to become second only to the United States, and India surpassed Italy in 2015 and by 2022 ranked sixth, ahead of France and Italy and Canada, with an output about 1.5 times that of Italy or Canada.

Leaders of the BRICS countries (MEAphotogallery / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Amid this, the G7 membership has remained fixed, with no new members other than Russia at one point. The G7 is described as a meeting of leaders of “major countries,” but what are the criteria for “major countries”? If economic heft is the key, then it is hard to explain why China (ranked second by GDP) and India (sixth) are outside the group while Italy and Canada, which have relatively smaller GDP than those two, are inside. If democracy is a criterion—since all G7 members are democracies—then the exclusion of China may be understandable, but it does not explain why India, also a democracy, is not a member.

India and China have been invited at the discretion of the host to participate as guest countries at some summits, but they have not become full members. There have been attempts to expand the G7: in 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump, as host that year, proposed adding South Korea, Australia, and India; in 2021, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, as host, proposed adding South Korea, Australia, and India. Both proposals failed due to opposition from other G7 members.

Is the G7 not a grouping of “major countries” based on economic power or democracy, but rather a gathering of “major countries” restricted to the West?

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi (center) and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson (left) participating in the 2022 G7 (Number 10 / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The G7’s influence

The second issue is the influence wielded by the G7. While the G7 is said to discuss many topics—economy, politics, international affairs—many of its agendas and conclusions benefit the G7 countries themselves. Such conclusions then influence other international gatherings like the G20, prompting other countries to follow suit. One example is corporate taxation. At the June 2021 G7 finance ministers’ meeting, a deal was reached to impose a minimum 15% corporate tax on companies regardless of where they are headquartered (※4). The following month, this agreement was taken up at the G20 in Italy, affecting countries like China, Russia, and India that are part of the G20, and ultimately all G20 members agreed to a similar corporate tax pact.

Three months later, in October 2021, 130 countries and jurisdictions were pressed to join a similar agreement, and a final announcement confirmed they had agreed.

In this way, decisions within the G7 affect the entire world, creating a top-down structure in which agendas flow from the G7 to the G20 and then to many other countries. In other words, rather than in democratic forums where all nations participate—such as the UN General Assembly or the Economic and Social Council—arrangements made by the seven economically powerful Western countries are applied globally.

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak answering questions from reporters (HM Treasury / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

This influence is also significant for Japanese media. Issues taken up at the G7 draw media attention, resulting in large increases in coverage. A major example is marine plastics. At the 2018 summit in Canada, plastic waste was on the agenda, and the Ocean Plastics Charter was issued urging action on marine pollution from plastics by five countries—excluding the U.S. and Japan. Triggered by this G7 summit, plastics issues that had received little coverage in Japan began to draw attention, and reporting volumes increased substantially compared with before 2017.

Another example is African poverty. At the 2005 G7 summit, Africa’s poverty and debt were major themes and drew wide attention. Media coverage likewise surged, with reporting on African poverty increasing sharply that year. However, although the issue received a burst of coverage at the time of the summit, reporting volumes later plummeted despite the problem remaining unresolved. Today, media attention to issues is often triggered by their appearance on the G7 agenda, but is that the proper role for the media? Traditionally, the media’s role has been to highlight social problems, draw attention to them, and thereby press governments and states for improvements and reforms. The order is now reversed, reflecting a tendency to follow elite countries and organizations.

Protests against the G7

Frustration with the G7—a bloc of economically powerful Western countries pursuing their own interests while exerting major global influence—has built up among civil society and others, leading to numerous protests against the G7. One of the most intense was the protest against the 2001 summit in Genoa, Italy. Carried out by groups dissatisfied with globalization and capitalism, it drew an estimated 200,000 people in Genoa, the host city. Protesters clashed with riot police, resulting in many injuries on both sides. A 23-year-old demonstrator was shot and killed, marking the first fatality in a protest against the G7 summit.

Protests against the G7 in Germany in 2015 were also large. Calling on G7 countries to address poverty and climate change, the protest drew thousands. Protesters clashed with riot police, who used tear spray and other means, causing many injuries. When Germany again hosted the G7 in 2022, protests erupted over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and calls for a transition away from fossil fuels, drawing around 4,000 people to Munich.

Scene from a protest in Germany in 2022 (cmpact / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Are the media reporting the problems?

So are the media reporting these problems with the G7 and raising issues? We examined Asahi Shimbun editorials over the 10 years from 2013 to 2022 whose headlines or body text mentioned the G7. We found 11 editorials whose main theme was criticism of or problematizing the G7. By topic, the most common—3 items—concerned the U.S. isolation at the G7 in 2017–2018 (※5), and these were the only ones that referred to a specific country. The other editorials focused on warning that the significance and authority of the G7 were waning (※6). None discussed representativeness—such as including India, a democratic country with a large GDP, in the G7—or assessed the appropriateness of the agenda.

We similarly examined Asahi Shimbun reporting that took BRICS, whose economic scale has grown to rival the G7, as a main theme. Over the 10 years from 2013 to 2022 there were only 29 such articles—less than one-tenth the G7 coverage. Some years had not a single article on BRICS, showing that it still receives very limited coverage.

We also checked how much protests against the G7 were covered, and found that over the past 15 years, not a single article made them the main topic (※7).

The future of the G7

We have looked at various aspects of Japanese G7 coverage. As it stands, coverage volume varies by host and by country, and overall reporting on the G7 has decreased substantially. Many of the G7’s problems are also rarely raised or reported. A body created to pursue Western countries’ interests is losing influence in the world. As common global problems increase and democratic forums where the whole world is represented are more needed, it may be time for the media to rethink coverage of the G7 and its significance—including the very name “summit of major countries’ leaders.”

[For coverage and realities of the G20, see here]

※1 In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a separate emergency G7 meeting was held in Belgium in 2022 in addition to the main summit. Similarly, in 2014, following Russia’s incursion into Crimea, an emergency G7 meeting was held in the Netherlands in addition to the main summit in June. Thus, only in 2014 and 2022 were there two G7 meetings in the same year.

※2 Because this survey counted items with “G7 (summit of major countries)” in the headline, it is possible that other articles mentioned it in the body text even if not in the headline.

※3 We examined these three years because there were no extraordinarily dominant topics such as Russia’s military invasion or the COVID-19 pandemic, and the G7 met as usual in all three years.

※4 This measure requires companies to pay corporate taxes in the countries where they provide products or services, with the aim of curbing the global race to the bottom in tax rates, and it affected multinationals such as Amazon and Google.

※5 Because this survey also counted only items with the keywords “G7 protests” or “BRICS” in the headline, it is possible they were mentioned in the body text of other articles.

※6 “An isolated United States: The G7’s true worth is being tested” (June 6, 2018)

“G6 plus 1: The U.S.’s self-righteousness brings anguish” (June 12, 2018)

“G7 summit: Uphold the ideal of multilateral cooperation” (August 28, 2019)

※7 “G8 and the world: Listing challenges is not enough” (June 20, 2013)

“The role of the G7: Advocate universal values” (March 26, 2014)

“The significance of the G7: A fresh start to seek a path of coexistence” (June 7, 2014)

“A sustainable world: The G7’s resolve is being tested” (May 26, 2016)

“G7 summit: The duty to uphold values remains” (May 29, 2017)

“G7 cooperation: COVID-19 response is the touchstone” (February 23, 2021)

“G7 summit: Implement declarations to rebuild trust” (June 15, 2021)

“G7 leaders’ summit: Be mindful of your heavy responsibility to maintain order” (June 30, 2022)

※7 Because this survey also counted only items with the keywords “G7 protests” or “BRICS” in the headline, it is possible they were mentioned in the body text of other articles.

Writer: Yudai Sekiguchi

Graphics: Yudai Sekiguchi

私は広島出身なので、今回のG7開催に対する県民の期待の高まりや市内のピリピリした雰囲気についてよく聞くのですが、今回のG7の会議で何かしらの成果が出てほしいと思う一方で、少数の国だけで決定が為されている現状はこれから変化していくべきだと感じました。

G7、主要7ヵ国という名前そのものが偉そうだ。自分で「主要」とかゆっちゃうのはずくないんかな?ぷはっ

タイムリーな話題ですね。今後のG7の動きと併せて必見だと思います。