In September 2020, Côte d’Ivoire, located in West Africa, approved Africa’s first legal process to protect stateless persons. Stateless persons are people who are not recognized as nationals by any country, and many face a variety of problems, such as the lack of guaranteed access to healthcare, education, and property rights. Côte d’Ivoire is said to have many stateless people. Behind this lie complex, intertwined issues including forced migration during the colonial era, political confrontations after independence, and armed conflicts involving neighboring countries. The following examines these backgrounds and Côte d’Ivoire’s current situation and outlook.

View of Abidjan, a major city in Côte d’Ivoire (International Monetary Fund / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Historical background

In West Africa, climate, styles of agriculture, and rivalries and conflicts have shaped ethnic groups and driven active population movements. Within the territory of present-day Côte d’Ivoire, many people moved for various reasons, leading to diverse ethnic formations. Rather than a single powerful group dominating, relatively small groups coexisted, each with its own governing system. Foreign incursions into what is now Côte d’Ivoire began in the 19th century, and in 1843 France built a fort on the eastern coast. However, full-fledged colonization began in the late 1880s. Thus, present-day Côte d’Ivoire was governed by France as part of “French West Africa,” together with what are now Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Guinea, and Benin. Through this relationship with France, the country came to be called “Côte d’Ivoire” (meaning “Ivory Coast” in French), “コートジボワール(Côte d’Ivoire)」, which became the origin of its current name.

France took note of Côte d’Ivoire’s fertile land, seized territory, and turned it into plantations. In doing so, people from neighboring colonies were forcibly relocated and made to work on cacao and coffee plantations. Due to this French migration policy, by 1960, out of a total population of 3.7 million, 13% had been born outside Côte d’Ivoire’s borders and had migrated there.

Politics after independence

Côte d’Ivoire gained independence in 1960, and from independence Félix Houphouët-Boigny of the Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI) served as president. Under President Houphouët-Boigny, Côte d’Ivoire achieved economic growth through the 1980s, known as the “Ivoirian Miracle” (“Ivoirien” refers to Côte d’Ivoire). During his era, prices for cacao and coffee produced on southern plantations soared. However, the gap widened between the developing south and the north. To address this, he promoted commercial food production in the north, but the north–south disparity persisted beyond his time.

Cocoa farmers in Côte d’Ivoire (Nestlé / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Amid economic development, President Houphouët-Boigny pursued a liberal immigration policy to secure labor. For example, by law he granted full rights as Ivorian citizens even to those who had not acquired Ivorian nationality. In the five-year plan from 1970 to 75, he declared that “farmland belongs to the farmers who use it,” promoting active land clearing and farming regardless of nationality.

Thanks to this liberal immigration policy, migrants from neighboring countries had no need to go so far as to acquire Ivorian nationality. This helps explain why there are many stateless people in Côte d’Ivoire.

In discussing the “Ivoirian Miracle,” we must note Côte d’Ivoire’s relationship with France. After independence, France sought to maintain significant influence over African countries in various ways, such as maintaining military bases and ensuring continued use of the colonial-era currency, the CFA (Communauté Financière Africaine, the African Financial Community; see note 1) franc, in West Africa. Under the CFA franc system (note 2), African countries find it difficult to implement free and independent economic policies, leading some to argue it is not true sovereignty.

The collapse of the “Ivoirian Miracle”

Côte d’Ivoire’s situation began to change with the collapse in global cocoa and coffee prices in the 1980s. National income declined, and by 1987 the country was on the verge of bankruptcy. In response, the French government devalued the CFA franc’s exchange rate by 50% in 1994, unchanged since 1948. The devaluation triggered inflation in Côte d’Ivoire, deepening economic crisis and poverty.

Amid this economic crisis, President Houphouët-Boigny, who had served since independence, died in 1993. As his successor, then National Assembly Speaker and PDCI member Henri Konan Bédié became acting president. However, some in the country believed that Alassane Ouattara of the Rally of Republicans (RDR), who had served as prime minister under Houphouët-Boigny, was the appropriate successor, establishing a political confrontation of “Bédié vs. Ouattara.” The outcome was to be decided in the 1995 election.

Ouattara’s family had lived in several places in what is now northern Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso since before colonization, and he enjoyed strong support, especially among northerners. It was also rumored that his father had been a village chief in Burkina Faso and that Ouattara himself had once acquired Burkinabè nationality.

Bédié focused on Ouattara’s background and amended the electoral law to block Ouattara’s candidacy. The amendment stated: “Anyone who is not at least 40 years old and who is not an Ivorian by origin born to an Ivorian father and mother may not be elected President of the Republic. Moreover, the person must never have renounced Ivorian nationality.” He argued that Ouattara was not ‘Ivorian by origin’, making it clear the law was aimed squarely at Ouattara.

In the end, Ouattara withdrew, and Bédié became the 2nd president. President Bédié intensified hostility toward “foreigners” and implemented discriminatory policies against those not considered “Ivorian by origin.” The Bédié–Ouattara rivalry was simplified into a conflict of “Ivorians vs. foreigners” and “south vs. north.”

In response to political instability and economic stagnation during Bédié’s tenure, in 1999 soldiers, protesting poor conditions such as unpaid salaries, launched a military coup. The coup resulted in a military regime under General Robert Guéï.

Immediately after the junta’s launch, Guéï claimed to be merely the spokesman for the mutineers, but he gradually grew more ambitious for the presidency. As Bédié had done, Guéï exploited the ideology of ivoirité. He incorporated into the new constitution the content of the electoral law Bédié had amended. Ouattara applied to run for president with documents showing that both his parents were Ivorians by birth, but he was suspected of fraud and rejected by the courts. However, because the junta’s supreme decision-making body supported Ouattara’s party and Guéï lacked strong allies, in the 2000 election Laurent Gbagbo of the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) defeated Guéï, who nonetheless declared himself the winner. The FPI under Gbagbo protested electoral fraud and, in an effort to exclude Ouattara’s RDR, repeated acts of violence in various places. Amid the turmoil, Guéï fled abroad.

President Gbagbo’s politics and the conflict

Having toppled the junta and become president, Gbagbo also implemented policies emphasizing ivoirité, taking a hard-line stance toward northerners—among whom Ouattara had strong support—such as excluding them from government. In July 2002, in local elections that served as an indicator for the presidential race, the opposition RDR won many seats. Those supporting President Gbagbo resented the formation of a government that would include the Ouattara camp, and tensions ran high nationwide.

In this context, in September 2002 the Ivorian conflict escalated. The spark was an uprising by rebel forces consisting of the Patriotic Movement of Côte d’Ivoire (MPCI) and two other groups (later the “Forces Nouvelles,” FN), whose core was soldiers who had fled abroad after the fall of the 2000 junta. The rebels attacked Abidjan, the de facto capital (note 3), and other government facilities. In these attacks, about 400 people, including Guéï, lost their lives. Around the same time, fighters from Sierra Leone and Liberia joined the rebels. There were also major population movements, with refugees from Côte d’Ivoire arriving in Liberia and Sierra Leone, and conversely refugees from Liberia and Sierra Leone arriving in Côte d’Ivoire amid the multiple conflicts.

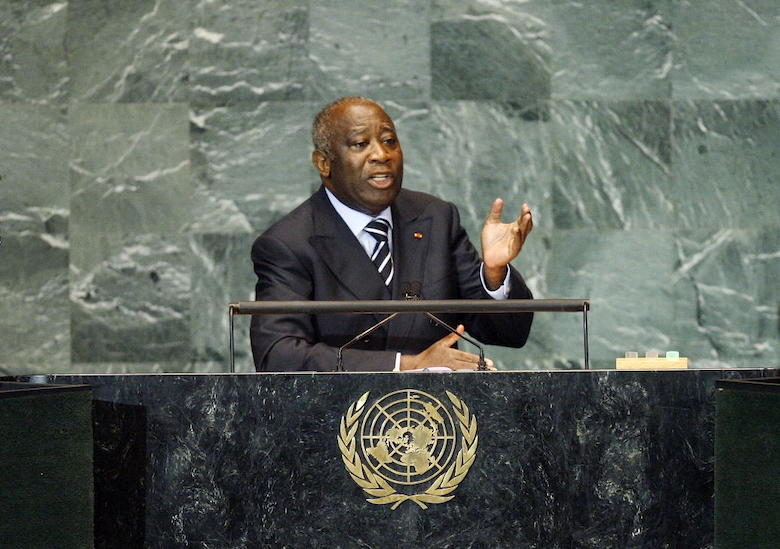

Laurent Gbagbo (United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

By mid-October 2002, the first ceasefire agreement had been reached. The rebels controlled the north, and government forces the south; French troops, ECOWAS contingents, and UN peacekeeping operations (UN PKO) were deployed to the buffer zone. Through the mediation of these bodies, in January 2003 the first basic peace agreement in this conflict, the Linas-Marcoussis Agreement, was concluded, based on three main principles: the need to preserve Côte d’Ivoire’s territorial integrity; the establishment of a Government of National Reconciliation led by a new prime minister; and constitutional revision to realize transparent and free elections that would not exclude people through improper eligibility requirements. The agreement also set a general election for October 2005.

President Gbagbo obstructed the implementation of the Linas-Marcoussis Agreement, particularly the constitutional amendment concerning eligibility to run for president. As noted, those in power since Bédié had blocked Ouattara’s candidacy by claiming he was not “Ivorian by origin.” The Linas-Marcoussis Agreement sought to resolve the conflict by eliminating the nationality and identity issues that had been instrumentalized in political strife. Ouattara’s candidacy threatened Gbagbo’s reelection prospects, and Gbagbo argued that revisions affecting presidential powers required a national referendum, and that with voter registration itself problematic, constitutional amendment was impossible.

Relations between France and Gbagbo deteriorated during the conflict. The trigger was an airstrike ordered by President Gbagbo in November 2004 on Bouaké, the main city in the north, which—whether by design or accident—killed 9 French soldiers. France retaliated by destroying the government air force.

Due to Gbagbo’s resistance, implementation of the Linas-Marcoussis Agreement stalled. As a result, the October 2005 election could not be held and was postponed by a year. Nevertheless, the postponed election was also not held, and the peace process stagnated. With Burkina Faso’s mediation, the Ouagadougou Agreement was concluded. The agreement gave President Gbagbo an advantageous position in the peace process, and with FN leader Guillaume Soro guaranteeing not to run for president, Gbagbo’s reelection prospects greatly improved, easing his wariness. After signing the Ouagadougou Agreement, Gbagbo became proactive in the peace process, and in July 2008 the north–south division of the country was overcome and national reunification was achieved.

UN PKO operating in Côte d’Ivoire (United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The first election in 10 years and a new conflict

As indicated in the Linas-Marcoussis Agreement, holding a presidential election was essential to ending the conflict, and it remained the goal after the Ouagadougou Agreement. In Côte d’Ivoire, the voter registration system to determine who is eligible to vote had been a major issue since the 1990s. Before the Ouagadougou Agreement, a national ID card was required for voter registration, and issuance of the national ID required both a birth certificate and a certificate of nationality, making proof difficult for many. In other words, those unable to prove their nationality could not vote and were excluded from elections. During the conflict period, administrative services were suspended in rebel-controlled areas and key documents were damaged or destroyed by the fighting, making voter registration extremely difficult. Under the Ouagadougou Agreement, only a birth certificate was required for voter registration, allowing the process to move forward significantly. A revision of the nationality law also made it possible for Ouattara to run. However, President Gbagbo postponed the presidential election, citing domestic turmoil.

After multiple postponements, the presidential election was finally held in 2010 for the first time in 10 years. Fourteen candidates ran, but the runoff came down to Gbagbo and Ouattara. Ouattara won with 54.1% of the vote. However, Gbagbo claimed that fraud had occurred in the northern regions where Ouattara had strong support and, excluding those votes, he would have won; he declared himself the “legitimate president” and held his own inauguration on December 14. The UN PKO observed that while there were some irregularities, they did not affect the outcome, and it recognized Ouattara’s victory. Based on this, Ouattara also held his inauguration on December 14. Côte d’Ivoire found itself with two presidents, which triggered a new conflict.

Gbagbo was urged to step down, primarily by the African Union, but he refused. From around February 2011, protests calling for Gbagbo’s resignation took place in Abidjan. Gbagbo responded with force, deploying government security units and causing many casualties. Pro-Ouattara armed groups seized most of the country for a time and besieged the presidential palace in Abidjan. The situation deteriorated to the point of UN PKO military intervention, and in April 2011 Gbagbo was finally arrested by the national army on Ouattara’s side. This brought the conflict in Côte d’Ivoire to an end.

It is estimated that about 3,000 people were killed in these four months of conflict. Gbagbo was arrested by the International Criminal Court (ICC) on charges of crimes against humanity (he was acquitted in 2021 and returned to the country).

Côte d’Ivoire today

Despite the many problems along the way, Ouattara finally assumed the presidency through an election. Has a stable future come to Côte d’Ivoire?

Alassane Ouattara (Paul Kagame / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The 2016 constitutional revision limited presidents to 2 terms. However, President Ouattara argued that the revision reset the count, making it his second term under the current constitution, and he ran for and won a third term in 2020. The opposition protested that this violated the constitution and boycotted the election. Political turmoil has not been completely dispelled, with at least 85 people killed in election-related violence.

Nevertheless, in July 2022 President Ouattara held a “fraternal meeting” with his former rivals, Gbagbo and Bédié, and showed a conciliatory attitude by granting Gbagbo a pardon.

Meanwhile, from 2020 to 2022 multiple military coups occurred in West Africa, which could increase the number of refugees entering Côte d’Ivoire. Moreover, even before the coups, armed conflicts persisted in Burkina Faso and Mali, leading many people to flow into Côte d’Ivoire. As of May 2023, 22,114 people had arrived in Côte d’Ivoire as asylum-seekers. Such population inflows from neighboring countries may again raise questions of nationality and identity within Côte d’Ivoire.

On the other hand, as time has passed since the end of the conflict in Côte d’Ivoire and the situation has stabilized, in June 2022 the recognition process for refugees from Côte d’Ivoire’s conflict was concluded. This could enable hundreds of thousands to return to Côte d’Ivoire.

However, there are other factors driving many to leave Côte d’Ivoire: economic migrants and refugees seeking to escape pervasive poverty. Underlying issues include persistently unfair pricing for exports such as cocoa. Many aim for Europe, undertaking arduous journeys.

In addition, the regional body ECOWAS has announced it will abolish the CFA franc, one factor in the collapse of the “Ivoirian Miracle,” and introduce a new currency, the Eco (Eco), in 2027. Under the Eco, it is said that France will reduce its interference in African countries by abolishing the obligation to deposit foreign reserves with the French Treasury and ending the dispatch of French representatives. Whether the introduction of the new currency will mean true independence from France is something to watch going forward.

Applying blue ink to distinguish those who have finished voting (United Nations Development Programme / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Conclusion

As discussed above, the background to nationality issues and other problems arising from migration in Côte d’Ivoire includes massive labor migration during the colonial era as well as political confrontations and armed conflicts. Beginning with Côte d’Ivoire’s approval of a legal process to protect stateless persons, statelessness has come to be addressed as a regional challenge for West Africa as a whole, not just for Côte d’Ivoire. ECOWAS, of which Côte d’Ivoire is a member, has worked with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to draft laws establishing statelessness determination procedures for the protection and resolution of statelessness. Côte d’Ivoire has announced it will resolve statelessness by 2024, indicating steady efforts toward addressing the issue. However, fundamentally resolving identity-based conflicts, including those over nationality, will require correcting disparities and eliminating discrimination.

※1 The acronym CFA originally stood for Communauté Française d’Afrique (French Community of Africa) during the colonial period, but after independence it was changed to Communauté Financière Africaine (African Financial Community).

※2 The main features of the CFA franc are the following three:

- A fixed exchange rate with the French franc (and with the euro after the euro’s creation)

- African countries must deposit 50% of their foreign exchange reserves with the French Treasury, plus an additional 20% for financial liabilities

- A French representative is dispatched to the board of the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO), which serves as the issuing bank for Côte d’Ivoire

※3 The capital of Côte d’Ivoire is Yamoussoukro, located inland, but Abidjan is the country’s largest city and serves as the de facto capital.

Writer: Misaki Nakayama

Graphics: Ayaka Takeuchi

普段日本ではアイデンティティで悩むことはない。植民地だった過去や発展の過程、争いで事態が複雑化しており、創造しにくい問題だと感じた。記事を通して、コートジボワールに興味が持てた。

コートジボワールについては西アフリカの国で元植民地だったことくらいしか知らなかったけど、この記事のおかげで独立後の政治が大まかに分かった。中南米諸国もそうだが、植民地支配から独立した国々は政情不安で軍事クーデターが非常に多い感覚。無国籍者に国籍を与えたら当然無国籍者は減るけど、無国籍のそもそもの問題(様々な権利が国籍に縛られてしまっているなど)は解決されないし根本的な原因の除去は達成できるんだろうか。

アフリカ地域における、ヨーロッパ諸国の介入がもっと知られるべきと感じました。コートジボワールがフランスの介入や影響を大きく受けているように、ヨーロッパの高所得国の影響で不安定な状況に陥っている国は多いと思います。それがほとんど知られていないという現状を、もっとGNVでも取り上げてみてほしいです。

コートジボワールといったらカカオくらいしかイメージしかなかったですが、権力争い、それに伴う紛争など、なかなか複雑な情勢がありますね、、

政治的対立に関して、丁寧に読んでいても混乱するほど複雑に絡み合っていて、解決するにも一筋縄には行かないのだろうなと思った。

現在、アイデンティティの問題は融和の方面に進んでいるように感じられるので、このまま逆行しなければいいなと思いました。