Haiti and its people are currently facing a crisis in every humanitarian, political, economic, and security dimension. With political instability and state governance collapsing, gangs and vigilante groups have risen and now occupy much of the nation’s capital. A food crisis has also emerged from a web of intertwined factors. How did it come to this? Behind it lies Haiti’s complex history. With that background in mind, this article examines the challenges Haiti faces today.

Woman waiting for food supplies (United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Haiti’s historical background

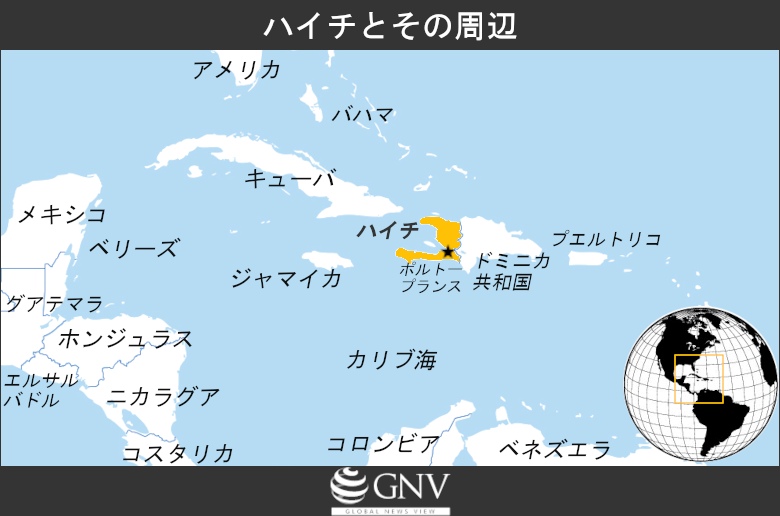

Haiti is a country in the Caribbean that, together with the Dominican Republic, forms the island of Hispaniola. Its population is about 10 million, and its capital is Port-au-Prince.

Let’s look at the history Haiti has gone through. The island of Hispaniola was originally inhabited by Indigenous people known as the Taíno. Later, France forcibly relocated large numbers of enslaved Africans there, and their descendants make up the majority of Haiti’s population. As a French colony, Haiti hosted sugarcane plantations and other enterprises, with most of the profits siphoned off to France. After enduring France’s oppression for many years, enslaved people rose up in 1804 and won independence. Haiti became the world’s first modern republic with a Black majority population. However, independence was far from straightforward. The main reason was the enormous indemnity Haiti was forced to pay to France as “compensation” for the loss of enslaved people. Valued today at about 22 billion US dollars, those payments continued from 1825 for a full 120 years, inevitably straining Haiti’s economy.

In 1915, after the assassination of the sitting president, the United States intervened in Haiti and occupied the country for 19 years, until 1934. During this period, the US ruled the Haitian people in a discriminatory manner and controlled the country through forced labor and press censorship. In response, Haitian peasants began rebelling in various regions around 1920. After nine years of uprisings, US forces finally began to withdraw, leaving completely in 1934. Even so, ties to the United States did not end, and the US continued to wield strong influence over Haiti thereafter.

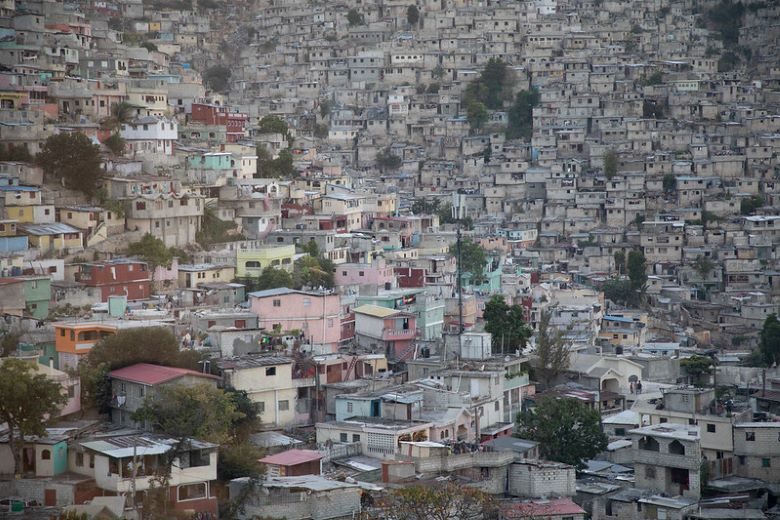

From 1957 to 1986, power in Haiti was held by a dictatorship led by President François Duvalier (nicknamed “Papa Doc”) and his son, President Jean=Claude Duvalier (nicknamed “Baby Doc”). François Duvalier took office in 1957 with popular support but soon turned to repressive politics. He organized a secret police known as the “Tonton Macoute.” Officially called the National Security Volunteers (VNS), its members sustained themselves by repeating looting and crimes such as seizing land from tenant farmers, terrorizing the populace. Farmers stripped of their land drifted to the slums of the capital in search of income, which soon became overcrowded and fell into a state rife with hunger and malnutrition. In stark contrast, key figures in the Tonton Macoute pocketed confiscated property and government subsidies, enriching themselves. Under state and regime directives, they also imprisoned major journalists and radio personnel on charges of incitement, imposing censorship. François Duvalier himself amended the constitution to make himself president for life, cementing a dictatorship.

When “Papa Doc” died in 1971, he was succeeded by his son, Jean=Claude Duvalier, who was only 19 at the time. He inherited his father’s dictatorial system, forming a repressive regime rife with corruption and misconduct. Such a regime could not last forever, however. In 1985, popular uprisings broke out across the country against the Duvalier regime, and the United States, which had long supported it, pressured Duvalier under the Reagan administration to step down. Unable to withstand pressure from all sides, “Baby Doc” fled to France in 1986, ending the two-generation dictatorship. The authoritarian political system that had long tormented Haiti also came to an end. A new constitution was enacted in 1987, and Haiti transitioned to a democratic state under it.

President Jean=Claude Duvalier (volcaniapôle / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

An unstable situation in Haiti

Even after the transition to the new constitution, peace did not come to Haiti. In the years following its enactment, the country saw a succession of coups and military regimes. The person who broke this cycle was Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who became president in 1991. For details of his presidency, see a GNV past article; here is a brief summary. He was the first democratically elected president after the new constitution and won the presidency twice, in 1991 and 2000, but was ousted during both terms. In both cases, the cause was a coup inside Haiti. In 2004, following his second ouster, Aristide was exiled and deposed, and this coup was deeply influenced by the United States, France, and Canada. During his administration, the US also heavily impeded Haiti’s industrial growth, and the effects persist to this day. For example, a flood of very cheap rice imported from the US at that time collapsed Haiti’s rice sector, and even now the country relies largely on imports for rice.

Aristide was ousted by coups in 1994 and 2004, and in both cases a United Nations peacekeeping force (PKO) came to Haiti afterwards. Notably, after the second ouster in 2004, a PKO arrived as part of the UN’s Haiti Stabilization Mission. They remained for 13 years until 2017, working on public security and rescue and recovery after the 2010 earthquake, but they also had severe negative impacts. Numerous cases of sexual violence by PKO personnel came to light, and it was revealed that cholera was introduced by peacekeepers in 2010, killing more than 10,000 people.

The major earthquake in January 2010 also contributed to Haiti’s instability. The magnitude 7.0 quake had a devastating impact on the country, killing over 200,000 and injuring more than 300,000. 70% of buildings in the capital collapsed in an instant. Among them were schools, hospitals, the Parliament building, and the Prime Minister’s office, leaving Haiti’s urban centers essentially inoperable, especially around the capital. The economic impact was also enormous. Landslides and other quake-related damage hit agriculture hard, preventing produce from circulating domestically and being exported. Transport and communications collapsed, logistics halted, and a catastrophic food crisis ensued, leaving many Haitians suffering from hunger as a result.

Armed PKO soldier (BBC World Service / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

The 2017 economic crisis in Venezuela also dealt Haiti a serious blow. Haiti had originally received economic support in the form of petroleum supplies from Venezuela. When Venezuela’s economy reached its breaking point in 2017, that support ceased, plunging Haiti into economic turmoil. The country suffered shortages of fuel and electricity and extreme inflation. In 2019, then-President Moïse was alleged to have engaged in corruption, including transferring 80 million US dollars in operating funds for petroleum supplies, managed by Haiti’s central bank, into his own account. Amid this turmoil, under the leadership of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Haiti’s government cut fuel subsidies and significantly raised fuel prices, which only made the situation worse. Fierce public backlash erupted, leading to large-scale protests.

An event that further escalated Haiti’s chaos was the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021. The attack was carried out primarily by mercenaries from Colombia, and the mastermind remains unknown. Reports also say there was no resistance from the president’s bodyguards, leaving many unanswered questions. With the country’s leader gone, a power vacuum emerged, bringing even greater turmoil to Haiti.

President Moïse after his assassination (Comision Interamericana de Derechos Humanos’s photostream / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Haiti today: the rise of gangs

After President Moïse was assassinated, Ariel Henry became the country’s leader as prime minister. He was appointed by the late President Moïse, but there are several questionable points about him. First, he is suspected of being involved in the assassination. Phone records show Henry spoke 12 times with a key suspect in the assassination, including a call of nearly 7 minutes on the morning of the attack. He says he does not remember the contents of the calls, but suspicion remains. Second, he was not selected through proper procedures. No election or parliamentary session was held for his appointment; he became prime minister by Moïse’s designation. The United States and Canada, which have no authority over Haiti’s internal governance, likewise urged him to take over and run the subsequent government. After taking office, he suddenly dissolved the electoral council, postponing the next election, and it remains unclear when it will be held. The constitution stipulates that the prime minister must be chosen by election. In other words, he has no constitutional authority. As noted at the outset, Henry lacks legitimacy, leaving the country without a legitimate authority and creating a power vacuum.

In response, civil society organizations and numerous political parties formed a coalition known as the Montana Accord. They challenge the Henry administration and work toward a democratic polity and state led by Haitian citizens, continuing negotiations with Henry’s side.

In the absence of a legitimate government, gangs and vigilante groups now effectively hold power in Haiti, producing the state of affairs described above. Gangs occupy much of the capital, Port-au-Prince, and surrounding cities, carrying out gun battles, violence, and kidnappings, ruling daily life through fear. In fact, in the capital, about 20,000 people have been displaced and forced into refuge. Some gangs have even occupied courts, destroying court buildings twice and pushing the justice system toward collapse to avoid being held accountable for their crimes.

Densely packed housing in Haiti (Comision Interamericana de Derechos Humanos’s photostream / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

The origins of these brutal gangs lie in the military organization National Security Volunteers (VNS), created by François Duvalier in 1959. Formed as a secret police during the Duvalier dynasty, they ran amok in the streets until being dissolved with the fall of the regime in 1986. When President Aristide disbanded Haiti’s military in 1995, they regrouped as gangs. Since then, they have built ties with politicians seeking electoral and political spoils, strengthening their power.

The most prominent figure among these gangs is Jimmy “Barbecue” Chérizier, leader of G9. A former police officer, he became known worldwide for his involvement in the La Saline massacre in 2018, in which 71 people were killed. He later formed G9 in 2021, a grouping of nine gangs in Port-au-Prince under his control. During President Moïse’s administration, it was revealed that they had received support from the government in the form of funds, weapons, and vehicles, showing close ties to the state. After Moïse’s death, Chérizier portrayed himself as a revolutionary fighting Haiti’s political elite to change state-driven inequality, and he has occupied Port-au-Prince and surrounding cities, controlling much of urban Haiti. In October 2022, the UN Security Council unanimously decided to impose sanctions on him, including asset freezes and a travel ban.

That said, the impact of armed groups in Haiti is not solely negative. Some groups labeled “gangs” do not engage in wrongdoing; in the absence of government, they act as vigilantes to protect their communities. As for G9, its formation reduced the number of clashes among armed groups, and ceasefires were reached among rival groups. After the ceasefires, the number of homicides also decreased.

Outlook

The Montana Accord has been working for over 1 year to transition from the Henry administration to a new democratic government, and in 2022 it held months of talks with Henry’s side over power-sharing. But in September 2022, the government announced the elimination of subsidies on gasoline and kerosene due to fiscal strain. This effectively meant domestic fuel prices would more than double. Civil society backing the Montana Accord reacted furiously, and negotiations between the Accord and the government collapsed.

Protests against the government, previously sporadic, became more intense. Notably, G9 occupied the country’s main fuel terminal for about 2 months from September to November 2022 as a form of protest. This caused devastating shortages of diesel and gasoline nationwide, forcing many hospitals and businesses to close as a result. The occupation ended after 2 months, but it reflected the depth of domestic anger.

Armed police officers (Comision Interamericana de Derechos Humanos’s photostream / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

In response, in October 2022 the government formally decided to request foreign military intervention. The UN, the United States, and Canada moved quickly. The UN Secretary-General and the US government requested a UN Security Council meeting seeking authorization for intervention. Specifically, they proposed deploying troops from multiple countries rather than a UN peacekeeping force. The US also dispatched diplomats and military officials to Haiti for emergency talks and announced that US Coast Guard vessels were patrolling waters near Haiti. The US asked Canada to lead the intervention, and Canada began considering the request, moving toward possible involvement.

But this request added fuel to the fire domestically. In Port-au-Prince, memories of past failed interventions, questionable motives, and harmful impacts prompted large anti-intervention protests. Police responded with tear gas and live rounds as clashes escalated. Civil society groups supporting the Montana Accord also issued statements opposing intervention. With strong domestic resistance, future developments bear close watching.

Haiti’s future

Foreign military interventions in Haiti have occurred many times, but none can be said to have ultimately improved the situation; rather, they have tended to worsen it in the long run. It is not unreasonable to suspect that the interveners’ interests have been prioritized. The United States and Canada have even supported coups and encouraged Ariel Henry’s appointment as prime minister while bypassing democratic procedures, disregarding Haitian interests and arguably undermining democracy itself.

Another intervention is now being floated, but it is easy to imagine history repeating itself. It would be wiser to rebuild the government from the ground up without relying on military intervention and establish a democratic administration. Despite the strong presence of armed groups like gangs, the Montana Accord is working toward such a democratic state. Of course, its influence has limits and many problems remain. Even so, starting here and taking the time to build a democratic state may be the first step toward improving the current situation.

Writer: Yudai Sekiguchi

Graphics: Yudai Sekiguchi

参考になります。ありがとうございます。