Over the past few months, Venezuela has dominated the news in many countries around the world. Long known for its abundant oil reserves, Venezuela was once a pillar of democracy and development in a Latin America rife with dictatorships. However, hyperinflation has brought shortages of food, medicine, and other basic services, prompting people to protest for relief and leading to violent clashes with a government trying to maintain order and power.

How did it come to this? The details are outlined below.

Protester confronting riot police. Photo: Efecto Eco (CC BY 3.0)

1959–1999: The road to populism

On January 23, 1959, the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez came to an end, ushering in one of the longest-lasting democracies in Latin America. Since then, a two-party system dominated by the socialist Democratic Action (AD) and the Christian Democratic party COPEI prevailed.

The first 15 years saw steady, diversified economic growth. However, the windfall from oil sales during the first oil crisis (1973) turned Venezuela into a so-called oil rentier state (“Rentismo Petrolero”), heavily dependent on oil revenues. Politicians, blinded by self-interest and political gain, moved to nationalize the oil industry. All infrastructure and oil-related facilities were expropriated and placed under the control of the newly created state company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). This “oil rentier state” strategy proved disastrous when oil prices plunged in the 1980s.

Citing resource shortages, failed economic policies, and populist political decisions, the government intervened to bring the once-strong bolívar under its control, triggering the economic collapse known as “Black Friday” in 1983. The bolívar lost half its value in just two months, sowing poverty in the years that followed. By 1989, mass riots known as the “Caracazo” erupted.

As conditions worsened and resentment toward democratic policies grew, two coup attempts were made in 1992. Both failed, but the first was led by Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chávez. After the failed attempt, Chávez was detained and imprisoned, yet he became popular among citizens as a symbol of defiance. Riding Chávez’s popularity, President Rafael Caldera ordered the charges against him dropped. This spared Chávez from prosecution and allowed him to run for president.

Buoyed by powerful rhetoric about social justice, overturning the status quo, fairly distributing oil revenues, and drafting a new constitution, Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chávez became president in February 1999. He called his government the “Bolivarian Revolution.”

Oil facilities in Venezuela. Photo: Jumanji Solar (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

1999–2013: The “Bolivarian Revolution”

The Chávez administration got off to a rocky start. In the first four years, amid poor economic conditions, its policies sparked many protests and strikes, and a new coup attempt was made, though it failed.

Although President Chávez faced a recall referendum in 2004, he survived it and, backed by increasing oil revenues (oil rose from US$10 per barrel in 1999 to US$36), launched a series of social programs known as the “Missions” (Las Misiones). These programs, while criticized by some, were widely accepted. Internationally, they were welcomed for reaching poor communities, even as critics denounced them as misuse of public funds and tools for propaganda.

After surviving the recall and consolidating power, President Chávez radicalized his economic and social policies under the banner of “Socialism of the 21st Century.” This led to the large-scale expropriation of private land, companies, and basic services, expanding the scope and workforce of the public sector. Government intervention in the exchange rate intensified, and prices for essential goods were fixed. These policies drew criticism from many in the private sector and from economists, though many citizens supported the reforms.

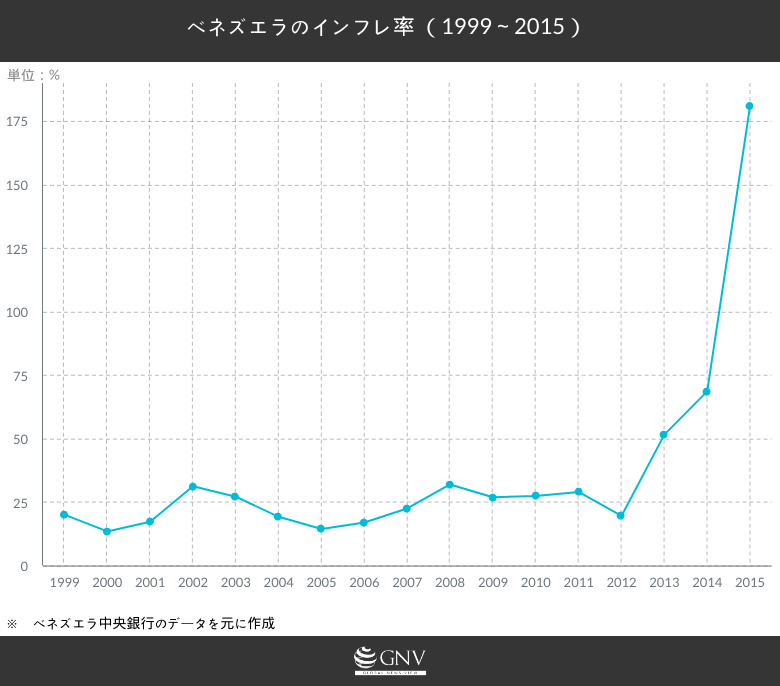

Domestically, the period was marked economically by rising inflation and frequent shortages of staples. These sparked protests that often clashed with government-led counterprotests, which reportedly included public-sector employees. Socially, violence increased, and by 2016 three Venezuelan cities ranked among the world’s ten most dangerous. Internationally, Venezuela wielded political influence over neighbors through cheap oil supplies, which allowed the Chávez government to deflect international criticism.

As the economy deteriorated, people looked for culprits. The government blamed an “economic war” waged by domestic (business leaders and the opposition) and foreign (the U.S., EU, etc.) forces. The opposition blamed Chávez’s “Socialism of the 21st Century” policies. Despite the dire situation, Chávez’s charisma sustained relatively high approval, and he won a third term in the 2012 elections.

Former President Hugo Chávez. Photo: Alex Lanz (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

However, just two months after his reelection Chávez announced the return of his cancer and that he would undergo treatment in Cuba. In his final address, he urged the nation to choose Vice President Nicolás Maduro as his successor should anything happen to him. On March 15, 2013, Chávez’s death was announced.

2013–2016: The “revolution” without Chávez

In April 2013, amid allegations of electoral fraud and by a narrow margin, Nicolás Maduro became Venezuela’s new president. However, Maduro lacked Chávez’s charisma. The worsening economy and falling oil prices badly hurt the government’s approval as it tried to lean on Chávez’s image.

Maduro sought to attribute the economic crisis to an “economic war” against the “Bolivarian Revolution.” To address the economy (and the resulting problems), his administration expanded price controls to almost all consumer goods and tightened military discipline. The opposition viewed these measures as excessively populist. By ordering retailers to sell below restocking cost, many firms went bankrupt, worsening shortages. People then had to queue an average of four to five hours to buy goods at controlled prices. As a result, a black market flourished, where items sold for many times the fixed prices.

Shortages in a Venezuelan supermarket. Photo: Matyas Rehak / Shutterstock.com

In 2014, shortages and runaway inflation triggered protests. Demonstrators clashed with police, the military, and pro-government armed groups known as “collectives” (Colectivos), leaving more than 40 people dead and leading to the imprisonment of Leopoldo López, a nationally trusted opposition leader.

Against this backdrop, the opposition won a commanding two-thirds majority in the National Assembly (AN) at the end of 2015, gaining real power to legislate. However, the ruling party under Nicolás Maduro and the Supreme Court (Note 1) moved to weaken the National Assembly’s authority.

2017: Escalating crisis

In April 2017, the Supreme Court stripped the National Assembly of its powers, expanding President Maduro’s authority. The decision sparked new protests. This ruling, an inflation rate of over 700% (Note 2), shortages of food and medicine, unrelenting violence (Note 3), a government refusing humanitarian aid, and a lack of progress in any attempted talks have all culminated in mass protests.

As in 2014, protesters faced harsh repression from police, the military, and the “collectives.” Over 100 people (mostly protesters) were killed in clashes, thousands were detained, and other human rights abuses occurred.

Amid these protests, President Maduro called elections to convene a Constituent Assembly (AC), tasked with drafting a new constitution. By law, voters should first be asked whether a new constitution is necessary, but the Supreme Court deemed that step unnecessary. As a result, elections for the Constituent Assembly were held on July 30, 2017. The opposition claimed the vote was unconstitutional and did not participate.

Not only the opposition, but also many foreign governments (including Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and the United States) and regional blocs (the EU), refused to recognize the Constituent Assembly’s decisions for the same reasons. The Venezuelan government denounced these stances as violations of sovereignty. In any case, a Constituent Assembly with broad powers was convened. Its powers include drafting a new constitution (its stated purpose), as well as amending, enacting, or repealing laws and appointing or removing public officials.

Since the Constituent Assembly’s launch, the Venezuelan government’s authoritarian turn has drawn strong condemnation. Venezuela was suspended from the regional bloc Mercosur, and leaders in the United States and the EU called for a restoration of democracy. Most notably, in August, U.S. President Trump stated that the United States would not rule out military intervention against the Venezuelan government.

President Maduro (second from right) attending a Mercosur meeting. Photo: Cancillería Ecuador (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The current crisis may be the worst Venezuela has faced. But the entanglement of politics, oil, and money underlying it has been lurking for decades. Unless that nexus changes, even a temporary exit from the crisis will not resolve the fundamental problems.

Note 1: All members of the Supreme Court were effectively affiliates of the PSUV, the socialist party of Chávez and Maduro, and were connected to the party.

Note 2: The Central Bank of Venezuela halted publication of data on inflation and shortages, claiming it could destabilize the political system.

Note 3: According to the Venezuelan NGO Observatory of Violence (OVV), in 2016 the capital, Caracas, was the most violent city in the world (140 homicides per 100,000 people), and Venezuela had the second-highest homicide rate in the world after El Salvador (91.8 per 100,000). Official government data are deeply in doubt.

Writer: Esteban Ibañez

Translator: Ryo Kobayashi

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks